“The Living, Breathing Embodiment of a Culture Transformed”

IN THE EARLY 1970S THERE WERE three epicenters for feminist art: Los Angeles, New York, and Fresno. Fresno, a mid-sized city in California’s Central Valley—far removed from San Francisco and Los Angeles—became essential due to the efforts of sixteen women: Judy Chicago and her fifteen students. In 1970, Chicago took a one-year teaching appointment at Fresno State University (now California State University–Fresno) to purposely remove herself from the art world. There, she started the Feminist Art Program—the first program in the country dedicated to a feminist art education.

Chicago did this for personal and political reasons. She had faced gender discrimination in her own art education, and in the male-dominated Los Angeles art world. Art historians rarely discussed the work of women artists, designers, and architects. Male art professors, who made up the vast majority of faculty appointments, treated female art students differently. Expectations were lower. Mentorship was often extended to male students only. Female students were not encouraged to be professional artists and designers.

Chicago sought to challenge sexism in the arts and to empower her female students. She began classes for the Feminist Art Program during the fall semester and held them off-campus. During the first six weeks, students held discussions at one another’s houses. Consciousness-Raising (C-R), a technique employed by the women’s liberation movement, was key to the learning environment. The class would sit in a circle and each participant would share personal thoughts about her experiences as a woman. This nonjudgmental atmosphere allowed each participant equal time to express herself. It also allowed her to realize that individual feelings and experiences were often shared experiences. Moreover, it allowed students to analyze how their lives had been conditioned and formed based on their gender.1

These C-R sessions produced art content in which students would return to class with poems, writings, drawings, and performance ideas based upon the discussions. Many of the women whom Chicago selected for the program were new to feminism; some were new to art. Suzanne Lacy and Faith Wilding, for example, had little formal art training. Lacy came to art through sociology: she was a graduate student in psychology at Fresno when she decided to switch majors and study with Chicago. Both Lacy and Wilding had started Fresno’s first women’s C-R group and had written a proposal for the university’s first women’s studies class.2

During its second month, the Feminist Art Program moved into a 5,000-square-foot space—former barracks—that became its studio classroom for the next seven months. Each student contributed $25 a month for rent. Here, students could organize and create an alternative space—a safe space—without male interference.3 The women constructed gallery walls, a darkroom, studio spaces, and a kitchen, directly challenging the notion that women could not learn or be skilled in the building trades. They also challenged the traditional education model. Instead of education being based upon the individual and the teacher as the primary instructor, their process became collective. Students helped develop the curriculum, which evolved organically. Wilding recalls, “Working off-campus in a building we controlled dissolved the normal academic time and space boundaries. We became part of the larger urban community.”4

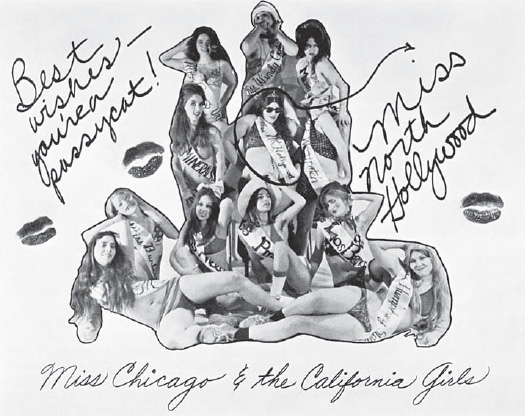

Feminist Art Program, Fresno State University, “Miss Chicago and the California Girls”, ca. 1970–1971, image ID: wb 3165, (Woman’s Building Image Archive, Otis College of Art and Design)

Many students began the program with three credit units and expanded to fifteen credits by the second semester, immersed in visual art, film, and performance art. Students staged a mock beauty pageant in their studio titled “Miss Chicago and the California Girls.”

They also formed a mock cheerleading team where each of the four participants spelled out the word “cunt” on their uniforms, turning a derogatory phase into an empowering one. “Cunt art” created a new visual vocabulary for representing female sexuality and the female body.5 In the words of Wilding, the images were meant to “analyze, confront, and articulate our common social experiences.”6

Other collective projects included editing the May 7, 1971, special issue of the feminist publication Everywoman. This issue was produced solely by the Fresno students and helped expand their audience. The students further broadened their reach with an open-house event at their studio in the spring. That weekend, several hundred women artists traveled to Fresno from Los Angeles and San Francisco to witness a series of performances, art exhibitions, discussions, and a slideshow highlighting the work of women artists. “That weekend, in tears, laughter, and night-long discussions,” says Wilding, launched, “the west coast women’s art movement . . . It was also the end of the Program as it had been, hidden and private in Fresno, away from the stress and pressures and male standards of the art world.”7

Feminist Art Program, Fresno State University, CUNT Cheerleaders, ca. 1970–1971; pictured: Cay Lang, Vanalyne Greene, Dori Atlantis, and Sue Boud (courtesy of Double X, Nancy Youdelman, Janice Lester, and Faith Wilding)

That fall, Chicago moved the Feminist Art Program to the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) in Valencia, just north of Los Angeles. Chicago brought with her nine of the fifteen students from Fresno and launched the Feminist Art and Design Program that she co-directed with the New York painter Miriam Schapiro.

Their signature project, much like the Fresno experimental educational model, took place off-campus. Twenty-one students spent six weeks restoring a city-owned Hollywood home slated for demolition and turned it into a temporary exhibition and performance space called Womanhouse, which critiqued the pop-culture image of the 1950s suburban housewife.

Students began by fixing up the seventeen-room dilapidated house, after which they each chose spaces for their own individual or collaborative installations.

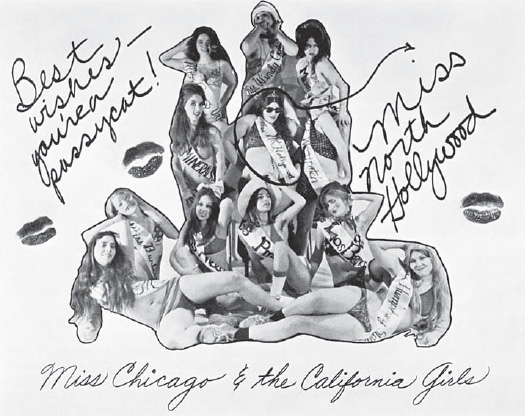

C-R techniques informed the process so that students and their instructors could tap into the gendered meanings of the conventional home—the kitchen, bedroom, bathroom, linen closet—and then turn these readings upside down. Camille Grey created Lipstick Bathroom, painting the entire room in gloss red. Judy Chicago also converted a bathroom to examine the taboo of female blood and fertility. Her Menstruation Bathroom was a clean and orderly environment, except for a trash can overflowing with used tampons. Other participants employed mannequins in their installations. Sandy Orgel segmented a female mannequin to fit inside the shelves of a linen closet, commenting on the housewife’s gendered confinement to household roles.

Womanhouse, group photograph of some of the participants, ca. 1971–1972. Top row, left to right: Ann Mills, Mira Schor, Kathy Huberland, Christine Rush, Judy Chicago, Robbin Schiff, Miriam Schapiro, Sherry Brody. Bottom row: Faith Wilding, Robin Mitchell, Sandra Orgel, Judy Huddleston. Not shown: Jan Oxenburg, Paul Longendyde, Karen LeCocq, Camille Grey, Nancy Youdelman, Shawnee Wollenman, Janice Lester, Beth Bachenheimer, Robin Weltsch, and Marcia Salisbury (courtesy of Double X, Nancy Youdelman, Janice Lester, and Faith Wilding)

Kathy Huberland installed a mannequin dressed in full bridal attire at the top of the stairs, absent her groom. Her installation expressed the essence of Womanhouse, shattering the veneer of the prototypical American suburban home and housewife by depicting a place where monotony, anger, despair, and loneliness replaced happiness.

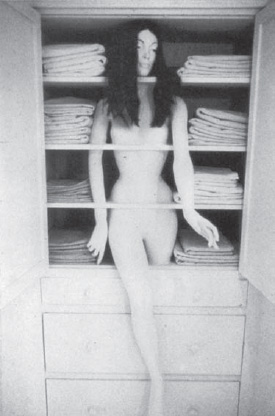

Women who attended the opening of Womanhouse connected to this message. That night, the space was open to women only. Spectators watched a series of performances, including Chris Rush’s Scrubbing, which had her methodically scrubbing the floor in an endless cycle of house chores, and Faith Wilding’s Waiting, for which she sat in a chair and listed a not-so-glamorous life cycle aimed to please others besides herself: “Waiting for my breasts to develop, waiting to get married, waiting to hold my baby, waiting for the first grey hair, waiting for my body to break down, to get ugly, waiting for my breasts to shrivel up, waiting for a visit from my children, for letters, waiting to get sick, waiting for sleep.”8

Sandy Orgel, Linen Closet, part of Womanhouse, 1972 (photograph by Lloyd Hamrol, courtesy of Faith Wilding)

Reactions to all the work ranged from tears to laughter. The following weekend, the performances were repeated for a mixed-gender audience. Men in the audience did not react as favorably. They apparently could relate to the critique.

During the month it was open (January 30 to February 28), Womanhouse turned a private space into a public dialogue. More than nine thousand people attended Womanhouse, and unlike the Fresno project, it received extensive national media attention. Time magazine and LIFE magazine both covered Womanhouse, as did local radio and television. Gloria Steinem showcased it for an hour on public television. Johanna Demetrakas made a forty-minute film about the project. This media attention expanded the reach and influence of feminist art, enabling it to challenge the influential New York art world and the long shadow it cast over art institutions and art schools throughout the country.

Christine Rush, Scrubbing, part of Womanhouse, 1972 (photograph by Lloyd Hamrol, courtesy of Faith Wilding)

The New York art world by and large championed formalist art, the commodification of art, and the notion of the lone individual artist. Feminist art countered all of these ideas about art and the artist’s role in society: it was overtly political, collective, and collaborative. Traditional media—weaving, needlework, and other techniques associated with craft—were reclaimed as contemporary art. New media—performance art, video, and installation art—were harnessed to express feminist content. Moreover, feminist art was part of the Second Wave of Feminism, a larger national movement that confronted patriarchy by challenging economic inequalities, cultural standards of beauty, and traditional views on gender roles, reproductive rights, and violence against women.

While the groundbreaking Womanhouse installation was an integral part of this movement, divisions existed among those who produced it. Some of the students resented the full-time nature of the project, which had them working from sunup to sundown. These pressures were exacerbated when Chicago and Schapiro would leave Los Angeles for stretches of time, traveling across the country to lecture about the Feminist Art Program and Womanhouse. When they would return, they would attempt to reassert control and authority over the project.9 Wilding reflects that some students resisted this breach in the collective process and “what they saw as an increasingly ideological formulation and application of the ‘feminist line’ to their art and their lives by Chicago and Schapiro.”10

Faith Wilding, Waiting, part of Womanhouse, 1972 (photograph by Lloyd Hamrol, courtesy of Faith Wilding)

Also present was the issue of recognition. Womanhouse was a collective project, yet the art world’s tendency to celebrate individuals meant that the most attention went to those with the greatest name recognition—primarily Chicago.

Additionally, Chicago and Schapiro’s Feminist Art Program was facing institutional resistance at CalArts. Other instructors and students were antagonistic toward the program, and feminism was not widely introduced across the curriculum. Students in the program thus learned one set of values from Chicago and Schapiro, and messages and values that countered feminism and feminist art in their other classes. Moreover, the two-to-one ratio of male students to female students hardly created a supportive environment. To complicate matters, tension existed between Chicago and Schapiro. Schapiro felt that being housed at CalArts was beneficial for the program, while Chicago came to view the Feminist Art Program’s relationship to the larger institution as a mistake.

The Woman’s Building

In 1973, Chicago resigned from CalArts to form the first independent art school exclusively for women—the Feminist Studio Workshop (FSW)—in collaboration with the graphic designer Sheila de Bretteville and the art historian Arlene Raven.

Woman’s Building founders; left: Judy Chicago; center: Sheila de Bretteville; right: Arlene Raven, ca. 1972 (image ID# wb3044, Woman’s Building Image Archive, Otis College of Art and Design)

Together, they chose the former Chouinard Art Institute—on 743 South Grand View Street, near MacArthur Park—which had fallen into disrepair and was ironically owned by CalArts, which rented it to them for $3,000 a year.

On November 28, 1973, after months of carpentry, painting, and repairs, a new epicenter for feminist art and activism—not to mention a model for alternative art spaces and art education—opened. Named the Woman’s Building after the Woman’s Building Pavilion at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, it housed the FSW and two other women’s art education programs, the Extension Program and the Summer Art Program.

Woman’s Building brochure designed by Sheila de Bretteville, ca. 1974 (image ID# wb74 1048, Woman’s Building Image Archive, Otis College of Art and Design)

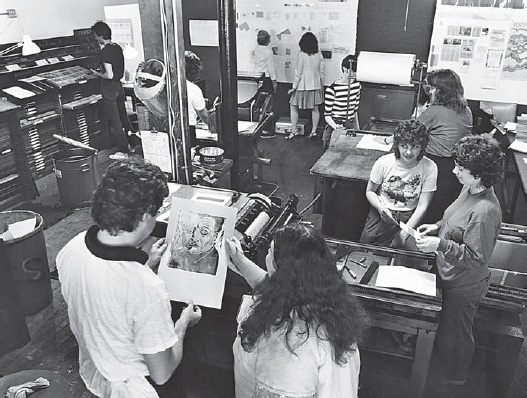

Women’s Graphic Center, ca. 1980s (mage ID# wb 3019, Woman’s Building Image Archive, Otis College of Art and Design)

It also housed the Women’s Graphic Center, run by Sheila de Bretteville and Helen Alm, which featured offset lithography presses, silk-screen, letterpress, and other printmaking techniques for creating broadsides, posters, newsletters, and artists’ books; women-owned businesses (Sisterhood Bookstore and the Associated Women’s Press, among others); seven galleries, including Grandview I and II, the Community Gallery, the Open Wall Show, the Upstairs Gallery, the Floating Gallery, and the Coffeehouse/Photo Gallery; performance-art spaces including Woman’s Improvisation and the Performance Project; and activist groups, including the Los Angeles chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW).

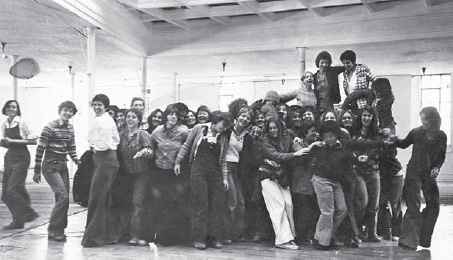

Group photo of the Feminist Studio Workshop (FSW), ca 1975–1976 (photo by Candace Compton, image ID# wb 30001 75, Woman’s Building Image Archive, Otis College of Art and Design)

For two years, the Grand View location became a hub of activity. Exhibitions, performances, lectures, readings, and workshops took place nearly every day of the week. Women—primarily white, middle-class women—from across the country enrolled in the FSW and immersed themselves in the activities of the Woman’s Building, training in new media, graphic arts, and feminist art (painting and sculpture classes were not offered).

Projects and groups that formed at the Woman’s Building during the 1970s included Mother Art (a space that welcomed women artists and their children), the Waitresses (a performance group confronting sexism in the workplace), the Lesbian Art Project (whose groundbreaking work included the performance An Oral Herstory of Lesbianism), and Ariadne: A Social Art Network (that connected women artists, collectives, and activist groups across the country), among others.

This separatist space and separatist feminist movement was needed. Women artists and designers were not deemed equal in the art world and the workforce. In the early 1970s, the Los Angeles Council of Women Artists reported that out of 713 artists who exhibited in group shows at the Los Angeles County Museum only 29 of them were women. Out of 53 solo exhibitions, only one was a woman’s.11 The Woman’s Building and the FSW supported women artists forging their own paths. It supported collectivity and collective action. All decisions at the Woman’s Building were made by a council that included one member from each group and tenant in the building. Cheri Gaulke writes, “Collaboration was a means of production, but at its best, it was also the living, breathing embodiment of a culture transformed. In many ways it represented our utopian vision of the world, where people were truly equal and everyone’s contribution was valued.”12

The Waitresses, The Great Goddess Diana, performance art vignette created as part of Ready to Order?, 1978; pictured: Anne Gauldin and Denise Yarfitz, photograph by Maria Karras (image ID# wb78.2009, Woman’s Building Image Archive, Otis College of Art and Design)

The Cast of Oral Herstory of Lesbianism, directed by Terry Wolverton, 1979 (image ID# wb70 2284, Woman’s Building Image Archive, Otis College of Art and Design)

Judy Chicago, whose vision helped create the Woman’s Building, left after the first year to focus on her own individual art career. Nonetheless, others carried forth the organizing efforts; the Woman’s Building allowed the alternative art space to become larger than any of the individuals involved. People could come and go and bring forth new ideas and new energy. The pressures of maintaining the space, however, were notable. In 1975, CalArts sold the building and the new owner ended the lease. Undeterred, the Woman’s Building, along with the FSW, moved to North Spring Street in an industrial corner of downtown Los Angeles.

Exterior of Woman’s Building—Spring Street location with Kate Millett’s Naked Lady sculpture on the roof, ca. 1980 (photograph by Mary McNally, image ID# wb 3051, Woman’s Building Image Archive, Otis College of Art and Design)

Internal group pressures also took a toll. In 1976, Arlene Raven wrote to Sheila de Bretteville, “Somehow I feel the need to feel like a separate person instead of a cog in our group/organizational wheel, marching as I have been these last years to the sound of what I think is my duty . . . I love what we’ve built even though its maintenance is burdensome.”13 Raven’s quote summarized the highs and lows of collective practices: the sacrifice of individual needs for the group’s benefit, and the intense amount of work needed to keep these types of spaces running, often on little funds and donated labor.

![]()

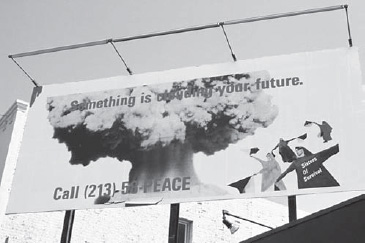

Sisters of Survival, Something Is Clouding Your Future billboard, 1985 (image ID# wb85 2195, Woman’s Building Image Archive, Otis College of Art and Design)

In the early 1980s, low enrollment ended the FSW and forced the Woman’s Building to alter its course once again. More space was carved out and leased to other groups to help pay the rent. Moreover, the focus of the Woman’s Building shifted toward coalition-building and global solidarity movements. While the 1970s called for a much-needed separatist movement that nurtured and empowered women, the 1980s demanded new tactics. President Ronald Reagan’s two terms in office ushered in a nuclear arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union, a covert war against leftist movements in Central America, the start of the mass incarceration of Americans—especially people of color (the War on Drugs)—a roll back on environmental protections, and an attack on unions. In general, Reagan’s policies represented a hyperprivatization of the public sphere that led to drastic defunding for public education and public services at the federal, state, and city levels. Cultural spaces were hit hard and had to scramble for funding. Furthermore, these policies embodied an affront to the gains made by the feminist and multicultural movements of the 1970s.

The Woman’s Building responded in kind. The Sisters of Survival, a group that challenged the impending threat of nuclear war, formed in 1981. The Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador also moved into the Woman’s Building, bringing men and more minorities into the space, something that had been lacking during the 1970s.

In 1991, the Woman’s Building project came to an end. Its influence, however, was felt by the tens of thousands of people who had passed through its doors as students, instructors, performers, artists, and visitors. It influenced an untold number of artists’ groups and spaces that formed during and after its incredible run.14 Cheri Gaulke reflects, “We were concerned with changing the lives of real women through our art, our activism, and our very organizational structures.”15 The Woman’s Building, along with Womanhouse and the Feminist Art Programs, achieved this goal; they each served as a safe space where a separatist movement could be nurtured, as well as critiqued and expanded upon.