Public Rituals, Media Performances, and Citywide Interventions

IN JUNE 1972, SUZANNE LACY, Judy Chicago, Sandy Orgel, Jan Lester, and Aviva Rahmani staged Ablutions, a one-night performance at a small art space in Venice, California. Audience members entered into an open studio room with a concrete floor that served as a temporary stage. Near the back wall was a single chair. In the middle of the room lay three metal tubs, each filed with a different substance—eggs, blood, and clay slip. Scattered across the floor were broken eggshells, rope, and animal kidneys. The stillness of the scene was ruptured when a naked woman was led to the chair in silence and slowly bound to it from head to foot with gauze bandages. Another woman walked unclothed toward the audience and the first tub. She began scrubbing herself in the bath of eggs and then proceeded to the second tub full of twenty gallons of beef blood, followed by the tub of slippery gray clay slip.

A third woman repeated her steps and entered the first tub. When the two women emerged from the final tub, the clay slip began to dry on their skin, revealing small rivulets of blood between the cracks on the surface. Simultaneously, other activities were taking place in the background. Lacy methodically pounded fifty beef kidneys into the wall with a hammer and nails, lining them up in a horizontal row. A tape recording played throughout the performance. The subject: women talking about their experience of being raped. The performance ended with Lacy and Jan Lester tying everything together with rope in a “spiderweb of entrapment” that connected the bound woman to the tubs, the two other women, and the beef kidneys. The tape recording repeated the single closing line, “I felt so helpless, all I could do was lie there and cry.”

The audience’s response was deafening silence. Cheri Gaulke reflected, “The powerful images shocked the art audience, who, like the general population, did not yet understand women’s experience of violence.”1 Talking about rape was taboo. Ablutions ruptured the silence.

At the Feminist Art Program at Fresno, Suzanne Lacy and Judy Chicago had begun conceptualizing Ablutions. They spent a year seeking out seven women who were willing to talk candidly (and anonymously) on tape about their experience of being raped. These interviews served as the basis for the audio for Ablutions.

Judy Chicago, Suzanne Lacy, Sandra Orgel, Jan Lester, and Aviva Rahmani, Ablutions, June 1972 (Suzanne Lacy)

The performance space operated as a safe space to address painful subject matter. Lacy writes, “The strategy of Ablutions was to convince the audience of the reality of the problem, to create a cathartic experience for rape victims, and to stimulate a cultural context for women to begin the painful process of speaking out.”2 The next phase was to move this dialogue into the public sphere. Lacy moved performance art out of the gallery and into the city, where the potential stage became the city itself. She asked, “Why talk about rape exclusively in an art gallery when you could still be attacked on the way home?”3

Citywide Interventions

Lacy’s first citywide public performance, Three Weeks in May, was launched on May 8, 1977. The project involved a three-week series of actions that confronted the rape crisis in Los Angeles. More than thirty events were staged, including performances, actions, speak-outs, radio programs, self-defense clinics, exhibitions, and demonstrations. Central to Three Weeks were community organizing, creating a media strategy, working with politicians, with artists taking on the role “as communicators, public spokeswomen for the cause of female safety.”4 Lacy explains that the goal of Three Weeks in May “was not only to raise public awareness, but to empower women to fight back and to transcend the sense of secrecy and shame associated with rape.”

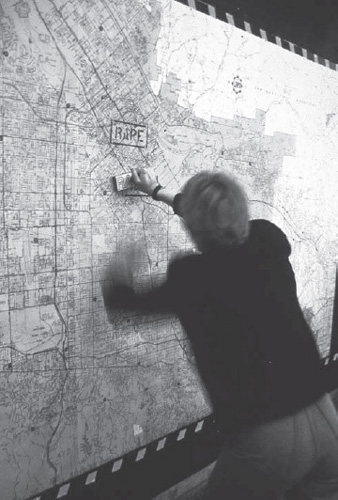

Lacy acted as a co-organizer, curator, and participant in the project.5 She installed two twenty-five-foot-tall maps of Los Angeles at the City Hall Shopping Mall, an underground shopping arcade in downtown L.A., next to City Hall. As daily rapes were reported to the Los Angeles Police Department, Lacy would stamp the approximate area of the map with a red stamp that read RAPE.

Suzanne Lacy stamping “rape” on map of Los Angeles in Three Weeks in May, May 1977, City Mall in City Hall, Los Angeles (Suzanne Lacy)

By the end of three weeks, the map had more than ninety stamp marks—a low estimate, considering that many rapes are never reported to the police. The other map detailed the locations of clinics, shelters, organizations, and other services to help assist women who were victims of rape and violence. Both maps were printed on bright yellow paper with a caution-tape border design as an outline.

Lacy and her co-collaborators chalked sidewalks in the city that noted the approximate location and the date when a rape had taken place. Sharon Irish writes that these simple but poignant words served as a “marker of violence and activated new meanings in locations that may never before have been associated with violence in most people’s minds.”6

Lacy also activated the City Hall Shopping Mall location by focusing attention away from consumerism and toward civic engagement and activism. The City Hall Shopping Mall, although underground and seemingly removed from the public, reached a critical audience. City officials and government workers who frequented the mall began to pay attention and began to offer more support. Members of the city government started to join the demonstration and began speaking publicly about violence against women. And when Three Weeks in May concluded, the city government and the police department took concrete action by publicizing rape hotlines.7

Chalking sidewalks near sites of rape, Three Weeks in May, May 1977, Los Angeles (Suzanne Lacy)

From the start of the project Lacy advocated that the government and the police play an important role in helping to reduce domestic violence, rape, and violence against women. On the other hand, she also communicated the role of artists in movements. During the planning stages for a subsequent performance, In Mourning and in Rage, Lacy had to explain to activist groups that artists were more than unpaid volunteers in a movement:

We had a meeting with all the women’s organizations in town that deal with violence, and we said we wanted to do this piece, and we wanted to support them. Immediately, one of the women from one of the centers jumped up and said we think the way you can support us is that you can help us do a self defense lecture-demonstration and then you can serve on the hot line and we need help doing that. And we said NO, we’re artists, and we have skills in this area and we’re going to talk with you about it. There was a struggle because they didn’t understand what we were trying to do as artists; they don’t trust art . . . so there was a struggle to educate them to what we can do, and about the power of this imagery and what it can do.8

In short, she helped bridge the gap between artists and activists.

On December 13, 1977, Lacy collaborated with Leslie Labowitz on In Mourning and in Rage, a one-day action on the steps of City Hall that encouraged women to fight back against sexual violence. In Mourning and in Rage was concieved in response to the media coverage of the Hillside Strangler case. The murders of ten women by two male serial killers (assumed to be one at the time) had placed Los Angeles on edge. Mainstream media only heightened the sense of fear and helplessness by running sensationalized stories of the murders that dug into the victims’ pasts and projected the storyline that women in Los Angeles were powerless to stop the violence. There was little public discussion or criticism of the culture of male violence against women, or information about women organizing and fighting back.

Lacy and Labowitz’s response to the media coverage was to create a public performance that would place a feminist counternarrative into the media’s coverage of the murder case. On the morning of December 13, Lacy and Labowitz (along with Bia Lowe) orchestrated a public action that was a “tableau enacted for the cameras” and “witnessed by the media audience.”9 Seventy women met at the Woman’s Building, including ten women dressed in specially constructed black mourning garb that made each wearer stand seven feet tall. Next, the ten women climbed into a hearse and drove toward City Hall under a motorcycle escort. Twenty-two cars filled with women from the Woman’s Building followed behind in the funeral procession. Each car had its lights on and had stickers that read FUNERAL and STOP VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN. When the motorcade approached City Hall, it circled twice and then pulled up to a sidewalk location, where the media had been instructed to wait. The ten women dressed in black and one in red emerged from the hearse, formed a line on the sidewalk, and then walked to the City Hall steps.

Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Labowitz-Starus, In Mourning and in Rage, performance at Los Angeles City Hall, 1977 (image ID# wb3044, photograph by Maria Karras, Woman’s Building Image Archive, Otis College of Art and Design)

On the steps of City Hall, a microphone was set up, and a banner was held behind the ten women that read IN MEMORY OF OUR SISTERS, WOMEN FIGHT BACK! The banner, much like the performance, was designed with the camera in mind. Lacy and Labowitz predetermined what the best spot would be for the media to set up so that the banner could be easily filmed and read through the medium of television.

The ten women each spoke. The first mourner walked up to the microphone and read, “I am here for the ten women who have been raped and strangled between October eighteenth and November twenty-ninth.” The nine women behind her echoed in unison, “In Memory of Our Sisters, We Fight Back!” Each of the nine women read a short statement, followed by the repeated chorus. Next, the woman dressed in all red spoke: “I am here for the rage of all women. I am here for women fighting back!” Lacy read a short statement, followed by a statement by the director of the Los Angeles Commission on Assaults Against Women, who demanded, among other things, that free self-defense classes be offered to women in recreation centers in the city. The performance then ended with a song by Holly Near, written specifically for the occasion.

In Mourning and in Rage was specifically choreographed to fit within the three-to-five-minute duration of a television news story and was designed to leave the viewer with a concise and didactic message to remember: women organizing, mourning the loss of other women, and, most significantly, fighting back.

In Mourning and in Rage, performance by Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Labowitz-Starus, Los Angeles City Hall, 1977, photograph by Maria Karras (Suzanne Lacy)

Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Labowitz-Starus, A Woman’s Image of Mass Media. 1977, photomural of In Mourning and in Rage, performance by Leslie Labowitz-Starus and Suzanne Lacy, photomural by Labowitz-Starus (Suzanne Lacy)

The performance also doubled as a press conference. Nearly every major television network in Los Angeles covered the event, and the action netted tangible results. The $100,000 reward for information about the Hillside Strangler was converted into a fund for free self-defense classes for Los Angeles residents, and two self-defense workshops were provided for city employees. Additionally, a reporter followed up on the event by asking the local telephone-book company why they had refused to list rape crisis hotlines in their books. This inquiry and the fear of negative press resulted in the phone-book company switching its policy and listing crisis numbers in the front of the book; unfortunately, the numbers were removed the following year.

Lacy and Labowitz’s action entered the bloodstream of the media not by chance but by careful planning. Both artists understood how the media worked, and how artists and activists could use it to their advantage. Lacy and Labowitz designed the action so that it would speak to the short attention span of the media and the public. “News demands clarity and simplicity, a straightforward narrative composed of two to four images, a message that can be explained in thirty seconds by a reporter who may only invest a few minutes of her or his time at the event,”10 Lacy said. Every detail was planned in advance. “We considered, for example, camera angles, reporters’ use of voice-over, and the role of politicians in traditional reporting strategies.”11 The result was a succinct message that made it difficult for media outlets to distort the message. For artists, the message was also clear: consider your audience and consider the messenger.