No Apologies: Asco, Performance Art, and the Chicano Civil Rights Movement

“It’s not in your best interests to apologize publicly.”

—Harry Gamboa Jr.1

WHOEVER SAID THAT POLITICALLY ACTIVE artists have to play by the rules and conform to the norms of a movement or a community? Not Asco, an East Los Angeles art collective that was founded by Harry Gamboa Jr., Willie Herrón, Gronk, and Patssi Valdez, and was active from 1971 to 1987. Asco (Spanish for “nausea”) was infamous for agitating nearly everyone from residents of East L.A., Chicano artists, the guardians of the art world, and participants of the Chicano civil rights movement.

An early action by Asco, Stations of the Cross, epitomized their desire to rupture public space and public norms. On Christmas Eve, 1971, Gamboa, Gronk, and Herrón led a procession down Whittier Boulevard in East L.A. amid holiday shoppers and curious onlookers. Herrón carried a fifteen-foot-tall cross, was dressed up as a skeleton (a Christ/Death figure), and wore a white robe and face makeup. Gronk was dressed as Pontius Pilate (or Popcorn) with a green bowler hat, carrying an oversized fur purse and a bag of unbuttered popcorn. And Gamboa dressed up as zombie altar boy, accented with an animal-skull headpiece. The one-mile silent procession ended at a U.S. Marines recruitment station, where a five-minute silent vigil was held. Gronk blessed the site and spread popcorn over the ground, while Herrón leaned the cross against the door, symbolically blocking the recruitment center that had sent so many community members to their death. After the vigil, Asco split the scene and left behind the cardboard cross and popcorn for the Marines to ponder their meaning.

Remarkably, the police never spotted them, but community members on the busy street did. At times, onlookers verbally assaulted them but did not attack them. Regardless, Asco had placed themselves in a dangerous situation where there was the potential for violent community reaction. Gamboa reflected:

Either the police were going to take care of you or someone in the neighborhood was going to take care of you. So you met a lot of resistance because it was so conservative. And to even to stray into the sensitive area of religious icons or even hinting that you might not believe in certain things or might even question what America is all about, again, you were setting yourself up to be someone that’s punished.2

Gamboa adds:

There were definite enforced roles bound up with growing up to be male or female . . . people would take it upon themselves to punish you for who you are. If you failed to comply with the rules or fulfill the requisite obligations, you could become the object of physical brutality at the will of the community by merely walking from one corner to another. There are countless experiences that I, personally, or other people I knew endured that involve such scenarios of admonishment and abuse as punishment for transgressions.3

To Asco, the risks were worth it. Stations of the Cross served as a litmus test for how far they could push their audience. They dressed up in makeup, subverted gender roles, and altered religious symbols. Ironically, Stations of the Cross focused on an issue that the community overwhelmingly endorsed: opposition to the Vietnam War. Yet Asco’s mode of communication defied conventions, asking the audience to dig deeper in search of the meaning of its artistic expression. Moreover, the performance critiqued both the war and the community. Both were violent, both were repressive, and Asco was not willing to give either one a pass.

Outside/Inside the Movement

Asco’s abrasive methods placed them on the margins of their community, but their engagement with community-based activist movements, especially Gamboa’s, made them anything but outsiders. Gamboa was one of a number of student leaders during the Chicano Blowouts, a watershed moment in East L.A. when thousands of students walked out of five high schools on March 5, 1968, demanding an overhaul of the education system.4

Students had good reason to walk out. East L.A. high schools had the highest dropout rate in the nation, and violence was at an epidemic level. Students would attack other students, teachers would attack students, and the police who patrolled the schools would respond with even more violence. Learning was all but nonexistent in this setting. “The schools were designed to create a product,” reflects Gamboa, “and the product was either soldiers for the war, cheap labor or prisoners. That was it.”5

In the early 1970s, Chicanos represented less than 1 percent of students in the University of California system, yet they filled the front lines of the military, representing the highest death rates in Vietnam.6 The Blowouts demanded changes in the schools: hiring more Chicano teachers and administrators, bilingual education, the end of rigid dress codes, and schools that were on par with those in the white districts of Los Angeles.

Gamboa’s leadership role in the Blowouts at Garfield High School made him a target for police and FBI surveillance. He was listed as one of the top 100 most dangerous and violent subversives in the country. His crime: helping to organize students to demand better public schools in East L.A.

Regardless of police intimidation, Gamboa’s activism continued after high school. He was one of 30,000 people who attended the National Chicano Moratorium March—a massive antiwar demonstration on August 29, 1970, at Laguna Park in East L.A. that turned into a riot when police stormed into the crowd and fired tear gas.7 Chaos ensued throughout the night, and by dawn, three protesters were dead, sixty-one injured, and more than two hundred people were arrested.8 One of those killed was Rubén Salazar, a Chicano journalist for the Los Angeles Times and news director for the Spanish-language television station KMEX. Salazar was killed when police fired a twelve-inch tear-gas canister at close range into his head as he sat inside the Silver Dollar Cafe. His death, and the acquittal of the officers responsible, sent shock waves through the Chicano community. Salazar was one of the prominent voices of the Chicano civil rights movement, and his murder at the hands of the police sent a clear message: Chicano people were deemed expandable, whether it was in the cities, rural America, or in Vietnam.

In the aftermath of the riot, Gamboa decided to turn to a new medium to voice his outrage: photography:

I saw cops [at the Moratorium] acting like dogs, but the next day in the newspapers the cops were represented as the victims: all the photographs were images of the cops getting hit. That’s when the idea hit me: they’re manipulating these images. All of a sudden, the pieces of the puzzle fit together: If I don’t capture these images and document the things I see, they’re going to get lost, and ultimately other people will define them for me. It seemed to hit all at once, perhaps because it was so traumatic and life threatening, not only for my family, and me but also for the whole community. So I got a camera, bought some film, and started taking pictures.9

Gamboa also turned to writing. Community activist Francisca Flores invited him on the day of the Chicano Moratorium to become an editor of Regeneración, a Chicano political and literary journal that had been relaunched from its early 1900s origins, highlighted by Mexican anarchist Ricardo Flores Magón’s involvement. Gamboa agreed and chose to expand the dialogue about Chicano culture and the Chicano movement itself. One of his first decisions was to invite Herrón, Gronk, and Valdez to contribute pen-and-ink drawings. The four soon began to collaborate, leading to the formation of Asco.

These four artists embraced dark humor and rejected the trends of Chicano art and mural art that looked to the past for inspiration. They had no desire to depict Mexican revolutionaries, Che Guevara, farmworkers, or images of Aztlán—the mythical homeland of the Aztecs.10 “A lot of Latino artists went back in history for imagery because they needed an identity, a starting place,” explains Gronk. “We didn’t want to go back, we wanted to stay in the present and find our imagery as urban artists and produce a body of work out of our sense of displacement.”11 Gronk added: “As an urban dweller . . . I couldn’t paint farmworkers because I would be deceiving people. I’m not familiar with those things . . . I want to communicate an idea, not just a slogan.”12

Willie Herrón and Gronk in 1979 in front of Black and White Mural, 1973 (photograph by Harry Gamboa Jr., copyright Harry Gamboa Jr., courtesy of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center)

This approach set the group at odds with the trends of Chicano activist art. During the First Chicano National Conference in 1969, a clear mandate was expressed through El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán: “We must ensure that our writers, poets, musicians, and artists produce literature and art that is appealing to our people and relates to our revolutionary culture.”13 Asco opposed this approach as one that disguised the reality of life in their community and one that would create a uniform artistic response. Instead, Asco chose to make art on their own terms: intensely political art that rose out of the barrio of East L.A. but shared more in common with the tactics and the humor of the 1920s avant-garde Dadaist movement. Gamboa and company named their collective Asco (nausea), a Dada-esqe “anti-art” name that perfectly summarized their opinion on American society, the Vietnam War, Chicano art and movement politics, and the reaction that most people had to their work.14

Asco, Walking Mural, 1972; left to right: Patssi Valdez, Willie Herrón, and Gronk (photograph by Harry Gamboa Jr., copyright Harry Gamboa Jr., courtesy of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center)

Instant Walking Murals

“We were right in the middle of it; we wanted to change it. We wanted to reach inside and pull people’s guts out.”

—Willie Herrón15

One year following the Stations of the Cross performance, Asco returned to Whittier Boulevard on Christmas Eve for another silent procession, Walking Mural. And once again, Asco held nothing back.

Gronk dressed as a Christmas tree, with a red-and-green dress and a five-pointed star painted on his face. Valdez dressed in black as the Virgin de Guadalupe, and Herrón dressed as a mural wall, one that had become so uninspired by the genre of mural painting and the demands of cultural nationalism that it decided to walk off the wall and down the street.16 Herrón’s costume featured three zombielike heads that protruded from the background and formed an arch over his own face that gazed out with a blank expression.

Asco’s intervention critiqued conventional murals, but it also addressed another key issue: restrictions on public space. In the aftermath of the Chicano Moratorium and a number of smaller riots, the city clamped down on Whittier Boulevard as an intimidation tactic to prevent further uprisings. Police routinely performed random stop-and-searches, and cars were prohibited from cruising down Whittier Boulevard after ten p.m. on weekends. The city also canceled the annual East Los Angeles Christmas parade. Asco’s Walking Mural was thus as an act of defiance against the city’s efforts to control the community. Walking Mural became an unsanctioned parade that reclaimed the streets and stood in solidarity with the community, albeit through avant-garde art that was garish and completely over-the-top. However, Asco won some converts with Walking Mural, and a number of onlookers and friends joined in with the procession.

Asco, First Supper (After a Major Riot), 1974 (photograph by Harry Gamboa Jr., copyright Harry Gamboa Jr., courtesy of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center)

On December 24, 1974, Asco performed another litmus test on the community and the police. They returned to Whittier Boulevard, this time on a traffic island during rush hour, to stage First Supper (After a Major Riot). Each member dressed up in costume and wore masks that twisted Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper and the traditional Day of the Dead celebrations into a new concoction. Props included a dinner table, chairs, food and drink, a painting of a tortured corpse, a skeleton, and a blow-up doll.

C. Ondine Chavoya described First Supper as an

act of occupation in lieu of their previously mobile tactics.17

The traffic island the artists occupied had been built over a particularly bloody site of the East L.A. riots as a part of an urban “redevelopment” project in 1973. Following the riots, the surrounding buildings, sidewalks, and streets were leveled and rebuilt to prevent further public demonstrations . . . an example of urban planning administered as a preventative obstacle and punitive consequence for mass social protest.18

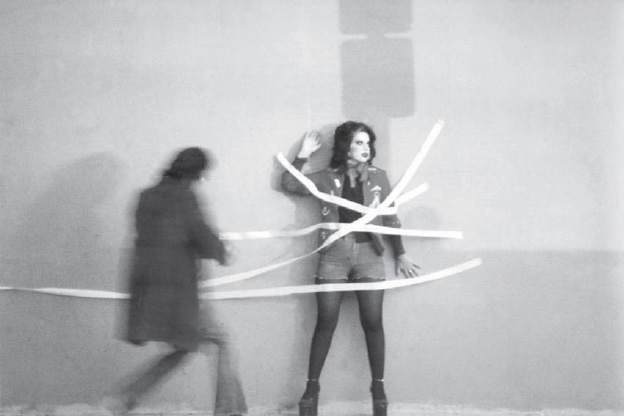

Asco’s response was to reclaim public space and to become more creative with their form of protest. Following First Supper, on the way walking home, Gronk took out a roll of masking tape and taped Patssi Valdez and Humberto Sandoval (a frequent co-collaborator with Asco) to the exterior wall of a liquor store, creating Instant Mural.

Gronk described the concept behind the spontaneous performance:

To me, the idea of oppression was that tape . . . It had a conceptual message—a thought-provoking one: how we are bound to our community and get bound to our environment. How we get caught up in the red tape.19

Asco, Instant Mural, 1974; left to right: Patssi Valdez and Gronk (photograph by Harry Gamboa Jr., copyright Harry Gamboa Jr., courtesy of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center)

Others could have read Instant Mural differently, and this was the point; the open-ended reading of Instant Mural defied the didactic modes of Chicano murals and kept the work raw, uninhibited, and cutting-edge—even with forty years of hindsight.

Museums and Decoys

“To be revolutionary is to be experimental.”

—Gronk20

Asco, Spraypaint LACMA, 1972 (photograph by Harry Gamboa Jr., copyright Harry Gamboa Jr., courtesy of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center)

Asco, Decoy Gang Victim, 1975 (photograph by Harry Gamboa Jr., copyright Harry Gamboa Jr., courtesy of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center)

Gamboa’s photograph of Valdez taped to a wall proved to be one of Asco’s classic images, exemplifying the importance that photography played in their work. It was designed with the camera in mind.21 Photographs and Super 8 films by Gamboa gave Asco’s ephemeral works an extended life and allowed the images to travel far and wide, away from the constraints of East L.A. However, not all of Asco’s work was situated in their own community. One of their most infamous works was performed at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). In 1972, Gamboa asked a museum curator, who likely did not know him, why contemporary Chicano art was absent from the museum’s exhibitions. The curator’s response was that Chicanos did not make “fine art,” they made “folk art” or they were gang members.22

Gamboa’s response was to give the curator a taste of his own medicine. He returned that night, after the museum was closed, and he, along with Herrón and Gronk, spray-painted their name “gang-style” on the side of the museum.23 Gamboa latter described Spraypaint LACMA (or Project Pie in Da/Face) as an action that “momentarily transformed the museum itself into the first conceptual work of Chicano art to be exhibited at LACMA.”24

As Chon A. Noriega writes, Asco’s tags did not last long: “When LACMA whitewashed Asco’s signatures, it simultaneously removed graffiti and destroyed the world’s largest work of Chicano art, obscuring the inclusive notion of the public that underwrote its existence.”25

While LACMA inadvertently tried to erase any notions of gang activity in Los Angeles, Asco created another performance to bring attention to the issue. Decoy Gang Victim (1974) addressed gang violence in their community, and used creative methods to try to stop it. The process involved showing up in the general region where a gang member had been killed or hurt, and setting off flares in the street. Next, Gronk would lie in the middle of the road, covered in ketchup, and pretend to be dead—the victim of a retaliatory killing, thus obviating the need for a revenge killing by a rival gang.

Asco took the action a step further by distributing photographs of the decoy to mainstream media outlets—a critique of the media’s habit of sensationalizing violence in the inner city. KHJ-TV News fell for the decoy and ran a photograph of Gronk on a live broadcast as a “prime example of rampant gang violence in the City of Angels.”26

Decoy Gang Victim resonates so powerfully, for it combined Asco’s avant-garde performance work with community activism, suggesting that their antagonistic relationship toward the community was equally matched by their efforts to improve it. For if they were truly outsiders, why would they risk life and limb to try to stop gang violence? East Los Angeles served as Asco’s subject matter, but it also was their home, and they employed art as a means to address the many problems that their community faced.

Asco’s work was designed to agitate, but it was also meant to inspire. “We were after the kids that were looking for something different,” reflects Herrón. “We wanted to find that little niche and create something . . . so if anyone wanted something alternative, they would turn to us for the alternative.”27 Herrón adds, “I felt we were doing it to expose them to art, to expose them to . . . looking at people that exist with them differently.”28

Asco achieved this goal, but their largely unwelcomed internal critique put them at odds with their audience. Their name said it all. Disgust with society, disgust with conventions, disgust with the way things were. Asco confronted the social and political problems of their time, and sadly ours—poverty, failing schools, high dropout rates, prisons, war, military recruiters, and racism. Their early work (1971–1975) was uninhibited and unstained by the art world.29 No matter what their medium was, Asco critically challenged the inequalities and violence that plagued their community and greater Los Angeles. They also critiqued the tactics of the Chicano movement and the Chicano artists who were addressing the same issues. They created what Max Benavidez called a “parallel art movement,” largely because other movements had rejected them.30