Art Is Not Enough: ACT UP, Gran Fury, and the AIDS Crisis

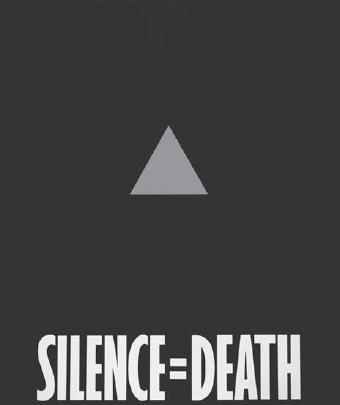

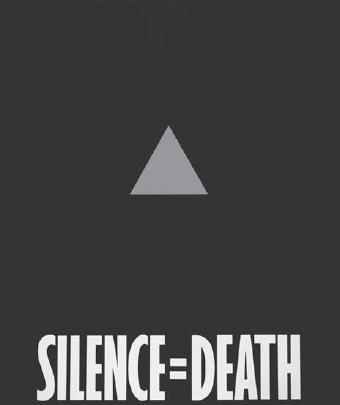

THE MOST ICONIC GRAPHIC OF the AIDS movement was arguably the movement’s most ambiguous—a pink triangle on a black background with text that read SILENCE = DEATH. To the viewer who encountered the image for the first time, the logical question became “Silence about what?”

By 1985, the number of reported AIDS cases nationally was more than 11,000. By mid-1986, this number was over 30,000, and nearly half of these individuals, primarily gay and bisexual men, had died.1 San Francisco gay activist Cleve Jones recalled that at that time “everyone’s address books were a mass of scratch-outs.”2 People were going to funerals every week. Entire social circles were being wiped out.

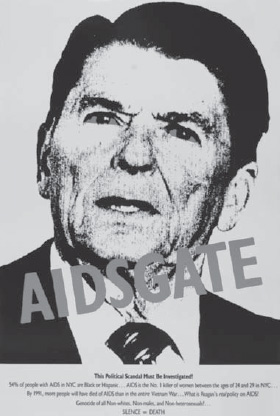

The government response to the AIDS crisis was shameful. Various government officials vilified gay and lesbian people instead of responding to a health emergency with compassion and expediency to find a cure. President Ronald Reagan was particularly callous. He pandered to the Religious Right and waited until the sixth year of his presidency before ever mentioning the word “AIDS” in a policy speech. And when he did, he proposed cutbacks in AIDS funding as well as mandatory-testing legislation that, if enacted, would only further demonize people with AIDS.

Other pundits went a step further. William Buckley wrote in a New York Times March 1986 op-ed piece that people with AIDS should be tattooed on their upper arm and buttocks to prevent the further spread of the disease. Not to be outdone, Lyndon LaRouche received the over 394,000 signatures required to place an initiative on the California ballot that called for people with AIDS to be placed in quarantine camps. This never came to fruition, but the climate of blame was deadly as funding for research and drugs that might slow down the virus, along with care for those already infected, remained substandard. Instead, the gay lifestyle and sexual “deviancy” was incorrectly deemed to be the cause of the AIDS virus that might harm “innocent” victims—children, hemophiliacs, and straight people.3

Silence = Death became an urgent response, not only to the deadly virus but also to the media hysteria and the political attacks that targeted the gay community. People with AIDS feared, justifiably, that the government might place them in quarantine camps. The Silence = Death graphic addressed this fear and the dangerous political and cultural climate. The pink triangle symbol referenced how gay prisoners in Nazi concentration camps were forced to wear pink triangles on their clothing before they were murdered, thus historically reinforcing that the failure to speak out was akin to death. The slogan and image became a call to action. To present an empowering message, the triangle pointed upward, as opposed to the Nazi image that pointed downward, and once the AIDS activist group ACT UP adopted the image, the message itself evolved. It was a call for direct action and creative resistance to force the government to adequately address the AIDS epidemic and help its citizens who were infected.

Silence = Death Project, Silence = Death, 1986, poster, offset lithography, placard, T-shirt, button, etc. (LGBT and HIV/AIDS Activist Collections, the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

ACT UP employed activist art with such success and at such at a high volume that they are almost without peers in terms of prioritizing culture as a form of resistance. Numerous art and video collectives were formed within ACT UP, including the Silence = Death Project (who created the iconic image in 1986), Gran Fury, Little Elvis, GANG, ACT UP Outreach Committee, DIVA TV, Testing the Limits, and House of Color. Their mediums included graphics, posters, T-shirts, installation, billboards, film and video, and performance art, among others. In ACT UP, artists were not simply asked to make banners or to design flyers—an insulting, and all-too-common role that artists are asked to fulfill in activist organizations. Instead, artists were active participants in ACT UP. They helped shape the organization’s mandate, identity, and tactics—including art as a form of direct action.

ACT UP

In early March 1987, more than three hundred gay and lesbian people gathered in New York City and founded ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power).4 ACT UP’s mandate was specific—“medication into bodies”—free access to antiviral drugs to help those who were infected and more public awareness to stop the spread of AIDS. ACT UP embraced direct action as the primary way to respond to the AIDS crisis, to force the government, pharmaceutical companies, and the media to respond. Each meeting began with members stating in unison that they were “united in anger and committed to direct action to end the AIDS crisis.”5 These words were quickly backed up in practice.

Silence = Death Project, AIDSgate, 1987, poster, offset lithography (LGBT and HIV/AIDS Activist Collections, the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

The first ACT UP/NYC demonstration took place just two weeks after the founding meeting. On March 24, hundreds gathered at Wall Street to protest the FDA’s slow approval process for drugs and the collusion of government and corporate interests that profited from the manufacture of AZT, the only FDA-approved AIDS drug, sold by the pharmaceutical company Burroughs Wellcome. AZT was a double negative; it was highly toxic and incredibly expensive. AZT cost patients more than $10,000 a year, despite the fact that the government had subsidized Burroughs Wellcome to develop it.6

During the protest, activists blocked traffic in the streets, an effigy of FDA commissioner Frank Young was hung, and seventeen people were arrested. In the aftermath, the demonstration made national news and CBS newsanchor Dan Rather credited ACT UP for bringing national attention to the issue. Several weeks later, the FDA announced plans to speed up its drug-approval process, and in December, Burroughs Wellcome announced plans to drop the price of AZT by 20 percent. The stunning success of the Wall Street action placed ACT UP at the forefront of the AIDS activist movement. In a short time, more than a hundred ACT UP branches were formed in cities across the United States and abroad, although the NYC branch would remain the most visible of the chapters.

Structurally, ACT UP was organized into a series of committees that allowed people to engage with the group depending upon their talents and interests. Gregg Bordowitz of ACT UP/NYC explains:

ACT UP [NYC] was not one monolithic institution. It was a group of people who met every Monday night. Many of them were parts of smaller groups, or cells, or affinity groups within the larger group. And those affinity groups to some extent had, if not a separate life, a life outside the group.7

Committees included, among others, a steering committee, a coordinating committee, and a women’s caucus. A majority caucus was formed in late 1987 because African Americans and Latinos represented the highest percentage of AIDS cases in NYC. For many, ACT UP became their social circle, dating scene, extended family, and way of life. Members would often go to different committee meetings nearly every night of the week.

ACT UP was also home to numerous art collectives that marked the organization from the very beginning. Michael Nesline, who was a member of the art collective Gran Fury, recalls how members of the Silence = Death Project first introduced themselves to the group:

Avram [Finkelstein] stood up and said, “I’m one of the people that made those posters [Silence = Death]. Most of us are in the room. We talked about it after last week’s ACT UP meeting, and we decided that we want you all to know that we made those posters and we want ACT UP to be able to use that poster and that image for whatever purposes ACT UP deems appropriate. So, it’s yours.8

The image would quickly be put into action, including during the New York City Gay Pride Parade on June 28, 1987. ACT UP blanketed the march with the logo on T-shirts and signs carried in the parade. Nesline explains:

What the media was impressed by was the uniformity of our presentation. I mean, all of the posters are black posters with big pink triangles. It looked really organized. That was not a completely conscious strategy at that point. It quickly became a conscious strategy, because we realized that it worked, for the media.9

But the images and slogans were not aimed just at the media and spectators. Cultural critic and ACT UP/NYC member Douglas Crimp argues that the primary audience for the graphics was people within the movement:

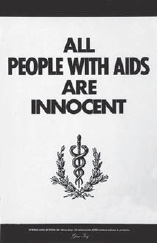

AIDS activist graphics enunciate AIDS politics to and for all of us in the movement. They suggest slogans (SILENCE = DEATH becomes “We’ll never be silent again”), target opponents (the New York Times, President Reagan, Cardinal O’Connor), define positions (“All people with AIDS are innocent’), propose actions (“Boycott Burroughs Wellcome”) . . . In the end when the final product is wheatpasted around the city, carried on protest placards, and worn on T-shirts, our politics, and our cohesion around those politics, become visible to us, and to those who will potentially join us.10

One of the most prolific of all the ACT UP art collectives, and the one responsible for much of the protest ephemera, was Gran Fury.

“We wanted to point out that the idea of the isolated cultural producer, the lonely artist in the studio, was one that at a time of crisis for us did not quite work, did not reflect the necessities or the possibilities of what collective action could do.”

—Gran Fury11

Gran Fury, a ten-to-twelve-person activist art collective within ACT UP/NYC, was formed in January 1988 and created myriad projects, including posters, stickers, flyers, billboards, bus ads, art installations, fake newspapers, and other forms of creative resistance.12 Gran Fury specialized in bold graphics and simple slogans—images were produced for actions, often the night before, and images were constantly repurposed.

The Government Has Blood on Its Hands followed this rubric.

Gran Fury, The Government Has Blood on Its Hands, 1988, poster, offset lithography, placard, t-shirt, etc. (LGBT and HIV/AIDS Activist Collections, the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

The poster was initially created for an ACT UP demonstration on July 28, 1988, against the New York City Department of Health (DOC) and NYC health commissioner Stephen Joseph. Joseph had enraged activists by stating that only 50,000 NYC residents had AIDS (instead of the more accurate number of 200,000) to justify the city’s minimal commitment to care services.13 The original poster featured a blood-red handprint with text that read YOU’VE GOT BLOOD ON YOUR HANDS, STEPHEN JOSEPH. THE CUTS IN AIDS NUMBERS IS A LETHAL LIE. An alternate version of the poster was aimed at Mayor Ed Koch for his failure to seriously address the AIDS crisis. It read NYC AIDS CARE DOESN’T EXIST, which was a bitter reality. Mayor Koch had provided a measly $25,000 in funding for AIDS research and patient care in 1983, compared to the $1 million that Mayor Dianne Feinstein had committed in San Francisco, a figure that was still too low.14 To address the failure of politicians in NYC, Gran Fury wheat-pasted the poster in the streets and “crews of ACT UP members went about with buckets of red paint, into which they dipped their latex-glove-covered hands to imprint bloody palm prints all over the city.”15

Other actions were just as confrontational. During the second Wall Street action on March 24, 1988, Gran Fury photocopied thousands of $10, $20, $50, and $100 bills onto green paper and scattered them all over the streets, causing traffic to come to a standstill. There were 111 ACT UP activists arrested while passersby and Wall Street brokers were invited to collect the fake bills; messages on the back of the bills read, among other things, “White Heterosexual Men Can’t Get AIDS . . . Don’t Bank On It” and “Fuck Your Profiteering: People Are Dying While You Play Business.” Gran Fury member Loring McAlpin reflected on the simplicity of the technique: “If you’re angry enough and have a Xerox machine and five or six friends who feel the same way, you’d be surprised how far you can go with that.”16

Some Gran Fury actions took more time and resources to create. ACT UP/NYC held the New York Times responsible for its abysmal reporting on the AIDS epidemic, consistently underestimating the scale of the crisis.17 The June 29, 1989, editorial “Why Make AIDS Worse Than It Is?” became the last straw. It argued that the virus was leveling off and was confined to “special risk groups,” saying in not-so-coded language that straight readers could relax while gay men and intravenous drug users died. In response, ACT UP demonstrated in front of New York Times editor Arthur “Punch” Sulzberger’s Fifth Avenue home in late July. Body outlines were painted all over the streets, fact sheets were handed out throughout the neighborhood, and a large demonstration took place. The Times never felt compelled to cover it.

Gran Fury, New York Crimes, 1989, four-page newspaper (LGBT and HIV/AIDS Activist Collections, the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

To further address the lackluster reporting, Gran Fury printed thousands of copies of their own version of a fake newspaper called the New York Crimes that included stories by ACT UP members and graphics by Gran Fury. The four-page paper mimicked the look of the Times and was placed in newspaper boxes during a late-night action.

Activists fanned out throughout the city at four in the morning, opened Times newspaper boxes, and wrapped each paper with the new-and-improved front-page section. Included in the Crimes was a full-page graphic of a laboratory scene with a quote by Patrick Gage of the Hoffman-La Roche pharmaceutical company: “One million [people with AIDS] isn’t a market that’s exciting. Sure it’s growing, but it’s not asthma.” Below the egregious quote, on the bottom of the image, Gran Fury simply added the commentary: “THIS IS TO ENRAGE YOU.”

Gran Fury, This is to Enrage You from New York Crimes, 1989, four-page newspaper (LGBT and HIV/AIDS Activist Collections, the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

As a small collective, Gran Fury members would meet at the end of ACT UP meetings on Monday nights and discuss project ideas. Anyone in ACT UP/NYC was welcome to take part. By their second year, the group became closed. A good working nucleus had been formed and it became too difficult to work with noncommitted people who would come and go. By their second year, Gran Fury began meeting once a week at someone’s apartment or studio. Here, they would debate ideas for images and actions, alter them, reject them, choose projects to take to the larger ACT UP meetings for discussions, and sometimes choose to do projects autonomously on their own terms. None of the artists in Gran Fury were paid, nothing was copyrighted, projects were credited to the collective’s name, and nothing was sold on the art market. Everything that Gran Fury created was for the AIDS movement.

Gran Fury’s drift toward more autonomous projects grew out of the frustration of seeing their finished ideas debated and overanalyzed by three-hundred–plus people at the Monday-night meetings. Michael Nesline reflects:

[Gran Fury] didn’t want to have to listen to ACT UP’s—why is it blue? Why shouldn’t it be green? We don’t want to have to listen to a conversation for 45 minutes about which is better, blue or green. We’ve already had that discussion, and we’ve decided it’s blue, and we’re not going to have the discussion again. And, we don’t really need to justify it, too. If you don’t like it, you don’t like it. So, tell you what—we’ll just do what we’re going to do, and if ACT UP is doing something, and we feel like piggy-backing onto that, we’ll piggy back onto that. And, if we feel like doing something on our own, we’ll do it on our own.18

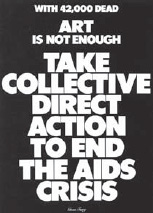

The poster With 42,000 Dead, Art Is Not Enough, Take Collective Direct Action to End the AIDS Crisis represented work aimed at an art audience.

The text-based image served as an advertisement for the NYC performance art space The Kitchen and communicated the need for both art and direct action to confront the AIDS crisis.

Gran Fury, Art Is Not Enough, 1988, poster, offset lithography (LGBT and HIV/AIDS Activist Collections, the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

Gran Fury clearly understood the dire need for art and cultural activism, but they equally understood the limitations of the medium. Art was not enough if it was isolated within the art world and understood primarily as a commercial object to exhibit and sell. Gran Fury knew that they could benefit from the contemporary art world. As Gran Fury evolved, they began to tap into artist grants to fund their projects and museum shows to gain more exposure for the issue. Nesline viewed this as a win-win situation:

Here’s this little Cinderella group [Gran Fury] that makes art that can’t be sold, because it doesn’t exist, and they’ll give us money so that we can produce our art projects, which are actions, and the art world can feel really good about themselves, because they’ve now contributed to the AIDS crisis—to ending the AIDS crisis—and we can feel really good that we’ve taken their money. So, we’ve used them, and we’re not going to give them anything in return, because there’s not going to be any art product at the end of it that can be re-sold and could accumulate in value. So, our status as Cinderella was preserved.19

In short, Gran Fury navigated both the activist and the contemporary art world. Their message was aimed at all.

“We are trying to fight for attention as hard as Coca-Cola fights for attention.”

—Loring McAlpin, Gran Fury20

Gran Fury’s two paths had a common source. Both approaches sought to bring as much public attention to AIDS as possible, and both approaches utilized design styles that mirrored commercial advertisements and the aesthetic style of some of the most prominent artists in the New York art world, including Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holzer, and Andy Warhol.21

What mattered to Gran Fury was that their images communicated to a mass audience. Whether or not their work was labeled “art” became inconsequential. “We were never articulating that stuff as artwork,” explains Gran Fury member Marlene McCarty. “It was other people who were doing that . . . we were only concerned about making a dent in the AIDS crisis . . . We were making propaganda.”22

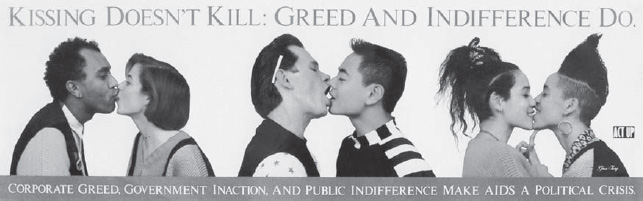

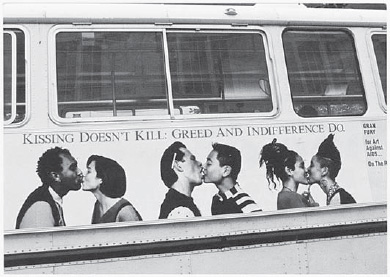

Gran Fury also never self-identified as a fringe movement or a countercultural movement positioned in opposition to the mainstream. Instead, they embraced popular culture and advertising in their graphics as a sign of belonging and demanded that gays, lesbians, and people with AIDS be accepted into American society. This demand was exemplified by their iconic image Kissing Doesn’t Kill, a 1989 bus ad that mirrored the look of Benetton’s clothing ad campaign “Colors of the World.”

Kissing Doesn’t Kill featured three couples kissing against a white background. Every detail of the design mimicked the Benetton ad. The people were young, of different races, and dressed in fashionable clothes. In the center, two gay men kissed, on the right two women kissed, and on the left, a cross-racial straight couple kissed. The Benetton ads had become a classic example of corporate branding—a slick campaign that pronounced that buying their sweatshop-made clothes would make you cool, a global citizen, and different from others who were not accepting of people of different races and nationalities.23 The Gran Fury ad also represented a form of branding—activist branding. Kissing Doesn’t Kill was designed to confuse the viewer on whether or not it was a Benetton ad.24 At the same time, it attached itself to the momentum, buzz, and hip appeal of the Benetton ad campaign and proudly projected the message “Our generation embraces all people and rejects racism and homophobia.”

Gran Fury, Kissing Doesn’t Kill, 1989, poster, offset lithography (LGBT and HIV/AIDS Activist Collections, the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

Kissing Doesn’t Kill, however, differentiated itself from the Benetton ads by adding text. The top line, “Kissing Doesn’t Kill: Greed and Indifference Do,” countered the public misconception that AIDS could be spread through casual contact. The lower text, “Corporate Greed, Government Inaction, and Public Indifference Make AIDS a Political Crisis,” framed the debate in ACT UP terms, targeting those responsible for not adequately addressing the AIDS crisis.

The first run of bus ads was funded by the NYC arts organization Creative Time, and ran on city buses in the Bronx with little controversy.25 However, this changed when Gran Fury was invited to include Kissing Doesn’t Kill on buses and subway platforms in San Francisco, Washington, DC, and Chicago as part of the traveling public art project Art Against AIDS On the Road, funded by the American Foundation for AIDS Research (AmFAR).

AmFAR had received significant amounts of funding from corporations and was uncomfortable with the sign’s second line “Corporate Greed, Government Inaction, and Public Indifference . . .” that railed against their benefactors. Thus, Gran Fury was faced with an agonizing decision: reject AmFAR’s request to remove the offending text and cancel the project, in full knowledge that Gran Fury could not fund it themselves; or go with the censored version of the design in the hope that reaching a large audience with a watered-down message might still bring much-needed attention to the issue of AIDS and homophobia.

Gran Fury, Kissing Doesn’t Kill, 1989, bus advertisement (LGBT and HIV/AIDS Activist Collections, the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

Gran Fury chose the latter—a decision that would become mired in controversy. The problem arose when Chicago city alderman Robert Shaw caught wind of the ad design that was scheduled to go up in advertising spaces in city bus shelters and subway train platforms. Shaw felt that images of gay couples kissing had nothing to do with AIDS, and instead, was meant to recruit children to be gay. With the second half of the message removed, the ad had become more ambiguous in its reading (even though some small text reading “Gran Fury, for Art Against AIDS, On the Road” had been added on the right side). Many viewers were equally confused by the ad’s intended message and believed that it was simply advocating for the rights of gays and lesbians to kiss in public, never making the connection to AIDS activism.26

Shaw’s homophobic reaction was to propose a citywide ban on the ad, a proposal that was voted down by the Chicago City Council. However, the Illinois State Senate took up the measure and enacted the ban on June 22, 1990. Worse, the State Senate went a step further and prohibited the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) “from displaying any poster showing or simulating physical contact or embrace within a homosexual or lesbian context where persons under 21 can view it.”27 The ruling, known as the “No Physical Embrace” Bill, became national news, prompting gay and lesbian activists and supporters in Chicago to march in protest and the ACLU to challenge the draconian bill as unconstitutional. Months later, the Illinois House of Representatives defeated the bill, and after much delay, forty-five Kissing Doesn’t Kill billboards were installed in August. Their run, however, was shortlived when vandals, intent on ridding the city of the ads, destroyed them all within the first two days.

The ugly situation in Chicago over the billboards provided some bitter lessons. Am-FAR’s decision to self-censor Kissing Doesn’t Kill had weakened its activist message and ultimately confused its reading.28 Whether Shaw and others would have attacked the ads had the full text been included is open to debate. But it is clear that AmFAR failed to realize that ACT UP graphics and slogans worked best when they were didactic and easy to understand.

![]()

As the AIDS epidemic continued into the 1990s, ACT UP began to move away from single-focus issues and began addressing health care, housing, poverty, and prisoners with AIDS. This broader focus addressed systemic patterns of inequality in American life, issues of class, race, and gender. These battles proved much harder to win. More troublesome, the shift away from single-focus campaigns created divisions within ACT UP, divisions that led to members leaving and the steady decline of the organization.

Gran Fury, All People with AIDS Are Innocent, 1988, poster, offset lithography (LGBT and HIV/AIDS Activist Collections, the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

Dilemmas were also created for artists who had a more difficult time visualizing the shift in focus. “You have issues that can’t be reduced to a billboard or a slogan,” recalls Loring McAlpin. “I think we just increasingly felt like we didn’t really know how to work in the same way.”29 Marlene McCarty adds

We were really great at just the over-generalization. After a number of years, the whole landscape of AIDS changed so much . . . we spent so many meetings towards the end, trying to decide how we were going to transform.30

During this time of transition, Gran Fury began to lose momentum as a collective in 1993, and by 1995 the few remaining members decided to call it quits. Regardless, the legacy of ACT UP continues to inspire others across the social justice spectrum. At a time when more moderate activists were still relying on petitions and marches, ACT UP turned to direct action and made AIDS front-page news. These tactics forced the media to cover the story, prevented the government from enacting repressive AIDS legislation, sped up the FDA drug approval process, and allowed people with life-threatening illnesses to get access to experimental drugs. ACT UP also forced pharmaceutical companies to significantly lower drug prices and expanded the definition of AIDS to include infections that impacted HIV-infected women, among many other victories.

Equally significant, ACT UP demonstrated just how effective graphics and creative resistance are when a group prioritizes cultural agitation. Artists acted as equals within the movement; the very structure of ACT UP allowed creativity to flourish within various cells, committees, and affinity groups. Gran Fury represented one such group and helped communicate the concerns of the movement to the public and to those within ACT UP.