ON DECEMBER 14, 1988, A group of artists met at the PAD/D (Political Art Documentation and Distribution) office in NYC and drafted a flyer that announced Groundwork: The Anti-Nuke Port Stencil Project. Its text read, in part:

The U.S. Navy is currently constructing a homeport for the Battleship IOWA and its support ships in the middle of New York harbor. An independent study has shown that that an accident involving the incineration of a single nuclear weapon containing plutonium-239 could release enough radioactivity into the atmosphere to cause up to 30,000 latent cancer deaths within 60 miles of the site. Our best hope for blocking the stationing of the Navy ships is to elect a city government opposed to the homeport. This stencil project is being organized to lay the groundwork for a broad effort to raise the issue in next year’s municipal elections. Conceived as a citywide environmental artwork, the project involves covering the streets/sidewalks of the city with stenciled variable markers.

E.g. 7.8 miles downwind of a nuclear Navy Base.1

A second flyer called out to artists: “Groundwork needs your stencils protesting the nuclear navy base being built in New York harbor—and you need Groundwork . . . With your images, we will blanket the city with thousands of stencils this spring and summer as municipal elections approach.”2

The ambitious goal originated with Ed Eisenberg, who came up with the idea shortly after he was arrested and convicted for demonstrating at the Stapleton site in Staten Island. Eisenberg was a radical Marxist, a gay activist, an artist, and a musician, the type of person whose practice and activism could not be easily categorized. In the mid-1980s, he became active with the Coalition for a Nuclear-Free Harbor, an umbrella organization that included 125 environmental-justice groups in the New York area. Eisenberg’s path as an artist led him to think outside the boundaries of typical activist strategies, and to consider how creative resistance could aid the coalition’s campaign. He teamed up with other like-minded artists. They envisioned Groundwork as an opportunity to cover the five boroughs of New York with 10,000 stencils during the spring and summer of 1989, a project that would employ street art as a means to get the public, and hopefully the media, talking about the dangers that the nuclear homeport posed. Media coverage, outside of the Staten Island Advocate, had been sparse and largely uncritical. More so, Mayor Edward Koch, along with Gov. Mario Cuomo, Sen. Alfonse D’Amato, and Sen. Daniel P. Moynihan supported the homeport. Opposition had to come from the grassroots level—from community members, the coalition, and from artists in the movement.

Organizing Against the Military Industrial Media Complex

Traditional forms of protest and lobbying marked the early stages of the antinuclear campaign in New York. In May 1985, coalition members began gathering signatures to place a referendum on the New York City ballot that would prohibit the use of city revenue for facilities with nuclear capabilities. Members gathered more than the 100,000 signatures needed to qualify the referendum, and polls indicated that it would pass, but city officials overruled it. A state court removed it from the ballot, citing a 1909 state law that empowers cities to provide land for the military. Lawsuits were filed, but the Navy went ahead anyway and began construction.

In response, the coalition moved toward more urgent forms of protest and began using their bodies to block construction. Activists erected a Statue of Liberty replica and planted a sapling tree on the site. Four months later, a small group of activists paddled canoes out to the site and halted construction for a few hours. On November 1, 1987, Pete Seeger performed outside the gates of the Stapleton site in a concert that doubled as a protest rally. The most confrontational moment had occurred four months earlier, when protesters entered the site on July 14 and refused to leave. Thirty-eight people, including Eisenberg, were arrested and charged with criminal trespass. Shortly thereafter, a campaign was launched on behalf of the “Stapleton 38” to drop all the charges. At the trial, historian Howard Zinn testified that the international antinuclear movement had played a significant role in shaping public policy. It had, but in New York, the media largely ignored the story, an omission that marginalized the movement. The New York Times’ reporting was particularly egregious. Leonard Marks, chairman of the New York Lawyers Alliance for Nuclear Control, surmised that “the [New York] Times has been totally co-opted in favor of the homeport from the very beginning. They have run almost nothing on any aspect of the protests, except an occasional photograph with no story when someone is arrested.”3 The Times even failed to adequately critique Mayor Koch’s emergency-preparedness plan that trivialized the dangers of plutonium:

In a hypothetical shipboard accident plutonium contamination will likely be confined to an area within 2000 feet and downwind from the accident site . . . Plutonium dust suspended in the air can be kept out of the lungs by placing a hanker chief [sic] over the nose and mouth or remaining inside a building with ventilation secured and doors and windows closed. . . . Even if one thinks they have inhaled plutonium it is not a medical emergency. It can be significantly eliminated from the body by medical procedures.4

Koch’s plan defied logic, as well as physics, and should have been front-page news. Instead it was not deemed newsworthy. Activists thus had to turn to other avenues of public outreach. Groundwork chose stencils.

You Could Die Here

“The paradox is that we have always been told that we have to have nuclear weapons to preserve democracy, yet now that we have them coming to New York City, democracy is being destroyed . . . In reality, no one in this country has been able to vote on nuclear weapons.”

—John Savagian, Coalition for a Nuclear-Free Harbor5

Groundwork required months of planning and fund-raising before stencils could first hit the streets. The call for artists had netted twenty-six original stencil designs and Eisenberg and other co-collaborators turned to well-known artists and art historians for financial support.6 They sent letters to Hans Haacke, Tim Rollins + KOS, Leon Golub and Nancy Spero, Lucy R. Lippard, the Keith Haring estate, and other allies in the art world. Contributors who donated $50 or more received a portfolio of the images printed on paper. This call resulted in enough funds to purchase supplies—one hundred cans of spray paint, maps of NYC, materials for stencils, X-Acto knifes to cut the stencils, and film to document their handiwork. The call also fulfilled another function: outreach and a permanent archive of the project. The prints sent to various regions of the country informed those outside of New York about the campaign and served as an example to inspire other artists and activists to learn about the tactics that Groundwork had employed.

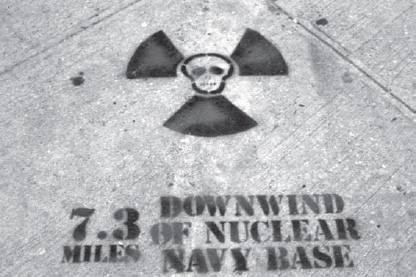

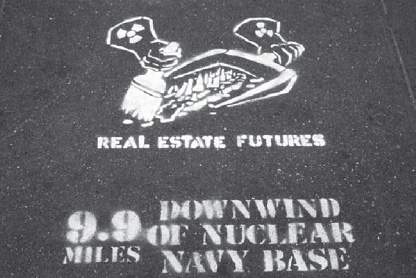

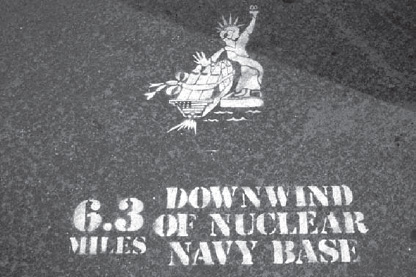

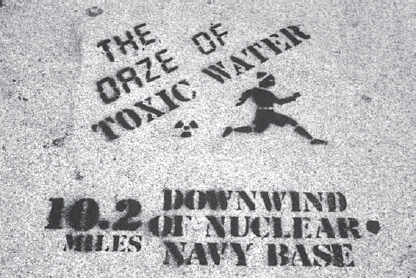

Stenciling of sidewalks began in the spring. Volunteers went out at night and targeted a specific area of the city. The plan called for each stencil design to be painted in either black or white spray paint, with a mile marker below it that informed viewers exactly how far they stood from the Staten Island homeport. Individual designs varied and included Mimi Smith’s image that read “You Could Die Here”; John Fekner’s design that featured a person running, with the text “The Daze of Toxic Water”; Gregory Sholette’s image “Real Estate Futures” that featured two hands wearing gloves with the nuclear warning symbol sweeping the city into a dustpan; and Rachel Avenia’s image that pictured a defiant Statue of Liberty pushing nuclear warheads away from her, metaphorically pushing the weapons away from the city.

On October 27, 1989, after months of painting, Groundwork held a press briefing in front of the Isaiah Wall on the west side of First Avenue, north of Forty-second Street in Manhattan. Groundwork took questions and invited the media to follow crews as they installed stencils at nearby locations. The media solicitation did not generate as much press as hoped, yet the process had signified the importance that Groundwork had placed on street art as a form of tactical media. Groundwork had sought media coverage to amplify their message; but with or without media coverage, the stencils communicated directly to an unsuspecting public and informed people about the proposed nuclear Navy base. Viewers were left to ponder who was behind the warning signs. The unsigned work and anonymous nature of the project left people to question if the message came from a neighbor, an organization, or the city government.

Stephanie Basch, Groundwork: The Anti-Nuke Port Stencil Project, 1989 (photographer unknown, Fales Library and Special Collections, Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, New York University)

The coalition’s aim was to make the Stapleton homeport an election issue. A Groundwork flyer noted that “stenciling has coincided with municipal electoral races with the intention of making the Navy base a campaign issue. A similar proposed homeport was canceled in San Francisco earlier this year after the election of an antinuclear mayor made it clear that Navy ships carrying nuclear weapons were not welcome in the city.”7 The same scenario would take place in New York City. Koch lost the Democratic primary to David Dinkins, who opposed the homeport and went on to defeat the Republican candidate Rudolph Giuliani, who supported it.

Gregory Sholette, Groundwork: The Anti-Nuke Port Stencil Project, 1989 (photographer unknown, Fales Library and Special Collections, Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, New York University)

However, Dinkins’s election proved to be only a partial victory in the struggle to keep nuclear weapons out of New York’s harbor; his power to stop the base was limited. Dinkins had called the homeport a “floating Chernobyl” and wanted the construction to stop even though it was 90 percent complete.8 His concern was for public safety. The Coast Guard had reported 609 accidents in New York Harbor from 1976 to 1980, and the Navy had even acknowledged 628 minor accidents on nuclear ships during the previous two decades. One reported accident was classified; another involved a missile falling off an aircraft carrier and into the sea. However, the federal government—specifically Dick Cheney, the secretary of the Department of Defense—had the final say, and he supported the Stapleton homeport. The nuclear ship USS Normandy was eventually docked in New York’s waters. Public pressure, however, did have a significant effect. In 1994, the homeport was closed through the Base Realignment and Closure Process. The Stapleton homeport in the end proved to be too small for the Navy’s needs, too costly, and too controversial.

Rachel Avenia, Groundwork: The Anti-Nuke Port Stencil Project, 1989 (photographer unknown, Fales Library and Special Collections, Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, New York University)

Groundwork’s creative action was part of a sustained campaign and a wave of opposition that ultimately defeated the homeport. Groundwork became a form of independent media and a compelling example of how street art could have an influence. Moreover, the primary focus on street stencils circumvented a reliance on the media, a relationship many activist groups and interventionist-type projects depend upon. If the media covered the action, and did not outright distort the story, it was a bonus. If they did not, 10,000 stencils placed throughout the city still had the power to communicate an antinuclear warning directly to the public.

John Fekner, Groundwork: The Anti-Nuke Port Stencil Project, 1989 (photographer unknown, Fales Library and Special Collections, Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, New York University)

The coalition’s choice to employ art as a form of tactical media—actions designed to enter the bloodstream of the public—was no doubt influenced by other activist art projects including those by ACT UP; Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Labowitz; and Louis Hock, Elizabeth Sisco, David Avalos, and Deborah Smalls, among others.9 Groundwork realized that for their action to gain even a ripple of attention in New York City, a place where hundreds of issues compete for attention, they needed to compete on the scale of the city. Thus, they covered the five boroughs of New York with 10,000 stencils and invited the press to help amplify the message.

Today, the stencils have long since faded from the sidewalks, but the action has not been forgotten, and neither has Ed Eisenberg, who died of AIDS in 1997. Tom Klem, who co-organized Artists for a Nuclear Free Harbor following the Groundwork project recalls that after Ed passed, he, along with REPOhistory collective members, stenciled “ED” in bright-red letters on sidewalks on the Lower East Side in Manhattan in a guerrilla art action in his memory. “We did not tell the press. It was just for us.”10