Living Water: Sustainability Through Collaboration

“Where is your well, your source of water for your home? Who cares for and shares this source? What does your community need to know to protect and restore their water? Why is this information not common knowledge?”

—Betsy Damon1

SINCE 1985, BROOKLYN-BASED ARTIST BETSY DAMON has raised critical questions through her art and activism about water in the United States and abroad. In 1990, she founded Keepers of the Water, a nonprofit organization that mobilizes artists, scientists, and citizens to collaborate, raise awareness, and ultimately restore water sources throughout the world.

Damon’s approach centers on the concept of “living water”—the purest form of a water molecule before it has been contaminated by the industrial landscape. To reverse the damage, a community has to go beyond simply cleaning up polluted waterways; it has to deindustrialize the areas around a water source so that water can function in its most natural state. A community has to allow nature to cleanse the water.

Cities rarely do this. Instead, problems caused by industrialization are treated with industrial responses. Dams are built, riverbanks are fortified with metal and cement, and wastewater treatment plants are introduced. All continue to harm water quality, human health, and the overall health of the environment.

Damon’s vision differs. She collaborates with the community to create a living water garden—a public park that demonstrates how natural systems can restore a river’s water quality. Her most famous reclamation project took place in China in 1995 on a six-acre site on the Fu-Nan (or Funan) River in Chengdu, a project where activist-based art played a vital role in mobilizing a city and a country to take action.

Why did she choose China for her project? And why did her previous efforts to do similar work in the United States run up against a brick wall? Damon explains, “We don’t acknowledge the role [water] plays in our lives. Chinese do, like all people who have a deep history, like Native Americans. People with a deep history understand on a profound level, not a gross level, the importance of water.”2

Process and the Underground Artist’s Web

Damon first traveled to China in 1989 with her son, Jon Otto, as a guest artist at a United Nations conference. In 1993, she returned to visit sacred water sites in the remote mountains north of Chengdu. Her search took her on a series of adventures, and she discovered opportunities to learn.

On one journey, she and her son traveled nineteen hours by Jeep up dirt roads to visit a water spring that had belonged to the Tibetans for thousands of years but that was now fenced off with barbed wire and designated by the Chinese government as a future water-bottling company. Tibetans were prohibited from gaining open access to their water source, but they continuously defied the order and cut holes through the fence to drink the water that was so pure, it was believed to cure stomach problems and reduce tumors. The Chinese government wanted to put the water in plastic bottles and sell it, a process that would kill the living-water state of the molecules, further deny the Tibetans their rights to their water, and devastate the ecology of the region.

Damon returned to China in 1995, this time with the intent to create a public art project about the horrid river water quality found in Chengdu, the city where the Fu and Nan Rivers converge. In the 1960s, the Fu-Nan was clean enough to swim in. More than fifty-six species of fish flourished. But as the population of the city grew from two million to nine million people, the river became a dumping ground. Some 60,000 cubic meters of raw sewage was dumped into the river on a daily basis, and 100,000 people lived in shacks next to the riverbanks. Factories discharged paint, paper, and chemicals into the water. The Fu-Nan became so polluted, the locals nicknamed it “Fulan,” meaning “rotten river.”

In 1985, a natural-sciences teacher in an elementary school in Chengdu inspired his students to take action. The students studied the Fu-Nan and began writing letters to government officials, who responded by launching China’s first large-scale environmental restoration project. Residents and factories were moved away from the banks of the river. The river was dredged; floodwalls were rebuilt; twenty thousand trees were planted; thirty-one miles of parks were established along the rivers, and plans for a future industrial waste-water treatment center were developed. Despite all these efforts, the Fu-Nan still remained polluted.

Damon’s response was to catalyze the residents and the government to take another step. The medium she used to raise awareness was temporary public art projects and performances. In 1995, she arrived in China on a tourist visa with little funding and a single contact, who introduced her to the director of water quality in Chengdu. At the same time, Damon began talking to local artists. She hitchhiked illegally to Tibet to meet with Tibetan artists. Damon recalls:

They [Tibetan artists] came down to Chengdu. By then word had spread in that wonderful way, quietly and through an underground web. Then artists came from Beijing and Shanghai and other cities. We all met twice a week. Everyone had to learn about the life of the river and the history of the river and the science.3

Simultaneously, the Chinese government closely monitored Damon’s every move. Police from Beijing interviewed anyone who had spoken or met with her. Finally, the Chengdu city government asked to meet with her. The officials were intrigued by her actions and engaged her in a conversation about the river. They showed her their plans and asked for her opinion. Damon recalls:

Their plan was impressive, but I knew they weren’t going to get a clean river. You build flood control walls and you don’t get a clean river. You dam it and you don’t get a clean river. They were sure they would. I said, “Why don’t you make a living water park to teach your citizens how nature cleans water?” They talked for thirty seconds and turned back to me and asked, “Can you do that?”4

Damon’s response was to nod yes.

The city government officials wanted her to abandon the performances and temporary installations and to design a living-water system. They felt that the ephemeral artworks were a waste of time and money. Damon, however, insisted that the performances and temporary installations had to happen. She owed this to the other artists and, of equal importance she felt the performances were an essential part of the process. The government responded by saying that if they liked the performances, they would invite her back to the table and continue the dialogue.

Damon moved forward, brought together twenty artists from China, Tibet, and the United States, and staged twenty-five projects during a two-week series of public artworks and performances on the banks of the Fu- Nan.

Kristin Caskey, an artist from the United States, organized a performance with six women from the community called Washing Silk.

Thirty years earlier, the Fu-Nan was a place where people could wash their silk in the river and it would come out brighter. This was no longer the case. In the performance, the women came down to the banks of the river and washed red rugs and baskets of silk. In a short time, the silk turned gray, and if the women stayed too long in the water, boils would begin to appear on their legs.

Kristin Caskey, Washing Silk, performance series on the banks of the Fu-Nan River, 1995 (Betsy Damon)

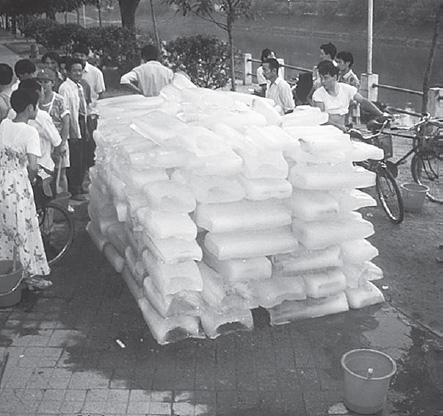

Another artist did an installation where water was gathered from the river and frozen into large blocks of ice. Next, the blocks of ice were stacked into a rectangle, roughly six by four by six feet, and placed on a sidewalk that looked down toward the river. The public was invited to wash the ice with brushes—metaphorically cleaning the Fu-Nan through collective action. The blocks of frozen river water slowly melted over the course of the three days, resulting in three days of intense public dialogue.

A different sidewalk installation involved an artist who placed black-and-white photographs—portraits of people’s faces—on white cafeteria trays that had a thin layer of river water on top. Over time, the water ate away at the paper, symbolizing the harm that filthy water has on human health. The artist also set up a stand to sell the river water in plastic bottles and invited the public to sign a petition. In this case, the artist directly merged public art with the call for political action.

Other installations took place on the river itself. One artist positioned a cable that ran across the river from one side of the bank to the other. Attached were brooms that hung just high enough as to touch the river’s surface as it rushed past. Seen from a distance, the brooms looked as if they were sweeping the river clean, washing the pollution away.

Unknown artist, performance series on the banks of the Fu-Nan River, 1995 (Betsy Damon)

Another artist chose to hang signs with text about the water quality around the necks of ducks. The ducks were then set loose into the river, where they proceeded to die.

All of these performances and installations were broadcast on state-run television. This, in turn, increased the dialogue between the artists and the public, a dialogue that led to a larger project.

A New Sculpture

Government officials in Chengdu responded favorably. They were impressed with the energy and the spirit of the performances and began to reconsider their approach to tackling polluted rivers with dams, floodwalls, and wastewater treatment centers. Zhang Ji Hai, the city’s Funan River Comprehensive Revitalization Project director, listened to Damon’s idea that the introduction of wetlands would educate the public on how to better care for the environment. Zhang agreed, and invited Damon to build her first living-water garden in their city.

Remarkably, Zhang risked his very freedom to move the project ahead. The Chinese premier opposed the park, and the mayor of Chengdu was not willing to go to jail if the project failed. Zhang was. He offered Damon a six-acre site on the banks of the river and a budget of $2.5 million to build the park.

Aerial view of the Living Water Garden, Chengdu, China, 1998 (Betsy Damon)

Collaboration was the theme. Damon worked with a team of hydrologists, scientists, engineers, landscape architects, and government officials.

In 1996, she returned to Chengdu with Margie Ruddick, a landscape architect from Philadelphia, and began designing. The land was serendipitously shaped like a fish, and the river water was designed to pass metaphorically through the creature.

Living Water Garden, Chengdu, China, 1998 (Betsy Damon)

The concept was to divert water from the river, let it flow through and be filtered by a series of wetlands, and then return back to the river. Most significantly, the design allowed the residents of Chengdu to visualize the process in a public setting: a park that would serve as a place for education, enjoyment, nature—a place where plants, insects, fish, wildlife, and people would flourish.

Water guided the design. After being pumped uphill from the river, the water entered the park and into the first settling pond—the eye of the fish. In the middle of the pond, Damon designed a thirteen-foot-tall sculpture, a water droplet made out of green granite that served as a fountain. The water then passed through a series of “flow forms.” These shapes, made of stones, encourage water to move laterally, to breathe, to move as water does in the mountains. Too often, people reconstruct nature and straighten rivers, dam rivers, prohibit the flow of water—all of which harms the integrity of the water molecule. After the flow-forms stage, the water enters into a series of wetlands—a dozen ponds where plants and fish further clean the water—and then into an amphitheater and splash ponds for children. Finally, it returns to the river, with a level of purity that meets the Chinese Category 3 environmental-quality standard for surface water.

Living Water Garden, Chengdu, China, 1998 (Betsy Damon)

Soon after the park opened in April 1998, the Living Water Garden became the most popular park destination in the city. Residents of the crowded city could find refuge in nature, engage with the river at a series of terraces that allowed people to walk down to the water’s edge—a unique feature, considering that large concrete floodwalls make the rest of the river inaccessible. Children discovered new worlds at the park.

Mary Padua writes

In almost every part of the park, children can be found kneeling or lying next to the stream and ponds trying to get a close look at water-borne insects and fish. This type of curiosity is a universal feature of childhood, but children in congested Chinese cities have few places like the Living Water Garden where they can satisfy a desire to learn about nature firsthand.5

Important to understanding the science of the living-water garden is that the diversion of river water through the six-acre park did not, and could not, clean the entire river. Padua notes

Living Water Garden, Chengdu, China, 1998 (Betsy Damon)

major improvements in a body of water the size of the Fu-Nan can be achieved only by reducing emissions of pollution. Instead, the impact of the Living Water Garden lies in its effects on the thinking of the people of Chengdu: their increased awareness of environmental issues and pride in the progress the city has made toward improvement of the river.6

Zhang echoes this sentiment. He noted that the Living Water Garden encourages “people to look at the world more carefully, to value each creek, river, and groundwater aquifer.”7

This is the true essence of the project. The park provides a symbolic space, a public space that teaches the community how to care for nature. It directly challenges the notion that industrial systems can solve environmental problems and asks everyone to become a better steward of the environment.

Zhang had risked his own freedom when he approved the project. His fortitude was honored when the project was widely praised, including praise from the Chinese premier, who commended the park after visiting the site.

Damon received an honorary citizenship to the city of Chengdu, and the project won numerous international design awards. All the while, Damon is quick to point out that the Living Water Garden was a collaborative project, one that was born out of a long process that included the performances and installations, and a diverse collaborative team who envisioned and built the park. She explains, “The park is not mine. That is a really important truth. We did it together.”8

Living Water Garden, Chengdu, China, 1998 (Betsy Damon)

She adds:

The Chengdu project is an extension of my philosophy of what it takes to live on the planet, the necessity of working together, bringing together unlikely partners, and forming new relationships. It is about building new kinds of connections and relationships while grappling with the consequences of a globalized class system and the economics of dominance, possession, exploitation, and greed.9

The project inspires future reclamation projects elsewhere, and future conversations about water. Damon asserts that water has to be the first consideration when building.

How are you going to catch the water? Where is it going to go? How are you going to filter it? Everything should be designed like that. Water is the foundation of life. It should be the foundation of design.10

Damon asks artists to create change, not simply to make more objects. “We need a new sculpture—we need a new language that describes the physical universe that we’ve come to understand from ancient times to now and a future language about preservation.”11 In the process, she utilizes art to engage the public to work toward solutions. “What can artists do?” Damon asks. “We can generate hope, possibility, and conversation.”12 This in turn leads to collaboration.

Artists must take a central role in helping people who do not traditionally work together find a common ground. Artists can help communicate scientific information to communities by finding a visual language. A public language does not mean that brilliance, excellence, and innovation are lost. Rather, the artist can help to create new patterns of thinking and infuse groups with the enthusiasm and common vision that are needed to break through the barriers.13

Aerial view of the Living Water Garden, Chengdu, China, 2007 (Betsy Damon)

The Living Water Garden, along with the performances and the public installations, achieved a breakthrough and led to tangible results. Mary Padua writes:

This unusual collaboration may be what is most important about the Living Water Garden. Environmental problems no longer are bounded by nationality or place, and constructive responses demand collaborations across national and professional frontiers.14

Damon, through example, champions artists to take a lead role in solving environmental problems. She asserts that artists, with their creativity, talents, communication skills, and ability to collaborate, are ideally suited to help redesign communities around ecology, public participation, and sustainability. She inspires artists to become activists.

Judith F. Baca, Danzas Indigenas, Baldwin Park Metrolink Station, circa 2005 (Social and Public Art Resource Center)