ON MARCH 19, 2007, MORNING commuters in Washington, DC, witnessed a terrifying scene outside Union Station. More than a dozen U.S. military soldiers rushed upon a crowd and began apprehending civilians. Soldiers yelled:

“Move!”

“Get down on the ground!”

“Get your hands behind your back!”

Eight people were detained. Their hands were tied behind their backs. Some detainees had sandbags put over their heads. Beside them, soldiers crouched, surveying the crowd for sniper fire, holding imaginary M16s in their hands and pointing them at the crowd. Some people in the crowd stood still, some screamed, others ignored them.

The soldiers were members of Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW), and they were reenacting their experiences of combat patrols in Iraq and reenacting what it was like to detain Iraqi civilians. They were bringing the war home, using street theatre to get the public to pay attention to what was taking place overseas and what the politicians, pundits, and media rarely discuss: the brutality of war and its effects on Iraqi citizens and U.S. soldiers alike.

Garett Reppenhagen, a former sniper with the 1st Infantry Division, explained why street theatre was needed:

Talking and marching wasn’t getting the point across. We wanted a demonstration that depicted what . . . we did. The average person could look at that . . . They can see what we are doing and see that the soldiers are going through a hell of a time and the occupation is really oppressive and violent and brutal on the Iraqi people.”1

Reppenhagen helped conceive the action, along with Aaron Hughes and Geoff Millard. The three veterans were frustrated by the cautious approach of antiwar demonstrations, exemplified by the massive protest march that had taken place in Washington, DC, a few months prior. As Hughes said:

All these people had come in from out of town and arrived on a Saturday—a time when representatives aren’t even in Congress. President Bush isn’t there. He’s not in the White House. He’s in Texas, in Crawford. And there’s this huge march. But everyone goes home afterwards. Everyone goes and sleeps in their own beds. No one’s willing to sacrifice to deal with the war. So we were pissed off. How do we make people deal with the war? Deal with it in a way where it’s a part of their life.2

Reppenhagen and Millard named their action Operation First Casualty (OFC)—the first casualty of war being truth. IVAW sent out a press release but never informed the police of their intentions and never sought a permit or permission. They dressed in full military uniform—minus weapons, flak vests, and Kevlar vests. They walked in the same formations they used during combat patrols in Iraq. They held their invisible weapons the same way, employing their memory of months of training and battle experience.

Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW), Operation First Casualty, ca. 2008, Denver, CO (photographer unknown, courtesy of Aaron Hughes)

Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW), Operation First Casualty, ca. May 2007, New York City, pictured: Garett Reppenhagen (photograph by Lovella Calica, courtesy of Aaron Hughes)

The detainees were friends—peace activists who agreed to act as if they were regular civilians. During the course of the day, thirteen veterans performed mock patrols in numerous sections of the city.

They did a vehicle search on the National Mall, and patrolled in front of CNN and Fox News (who refused to interview them). They were briefly detained themselves by police officers on the U.S. Capitol lawn. Hughes recalls:

The cops actually surrounded us and a couple of SUVs pulled up. We were still on the Capitol grounds and as soon as we saw that the police were starting to surround us, we immediately got into formation, which is what we practiced the day before.3

Hughes continues:

We had a police liaison stand in front of our formation. When the cops came up to us, they really did not know what to do. We were more organized than they were. We were more disciplined than they were. All of a sudden they realized that we were not this mob that they could go up to and pull one person aside. They had to deal with us as a community, as a force together.4

For IVAW, the action was a way to force the public to recognize the trauma that the soldiers had experienced and to make a political statement against the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. It reinforced the primary goals of IVAW: an immediate withdrawal of occupying forces from Iraq and Afghanistan, adequate care for the physical and psychological health of veterans, and reparations for the human and structural damages that Iraq has suffered from the military occupation.

IVAW had formed in 2004 at the Veterans for Peace (VFP) convention in Boston. By the end of 2006, IVAW had transitioned from a speakers’ bureau, where churches or organizations would call them requesting a veteran to speak at an event, to a membership-run organization where chapters would stage their own events and campaigns. By 2009, IVAW had sixty-one active chapters, including six on military bases, and a membership of over 1,700 veterans and active-duty service members across the United States, Canada, Europe, and Iraq.

Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW), Operation First Casualty, ca. March 2007, Washington, DC, pictured: Charles Anderson (photograph by Lovella Calica, courtesy of Aaron Hughes)

Creative resistance is central to IVAW’s tactics. Their actions are decentralized and arise from the creativity of individual members and chapters. Nothing is mandated from a central leadership. Hughes explains, “There is a real fear with being authoritative within a veteran community when you’re coming from a completely authoritarian structure such as the military.”5 Their creativity derived from soldiers’ need to heal and the need to speak out. The war had been pitched to the public as “Operation Iraqi Freedom”—a just war where U.S. soldiers would liberate the Iraqi people from a brutal dictator. IVAW argues that, in the process, the United States imposed a state of martial law, turned Iraq upside down, and opened it up to allow multinational corporations to come in and reap fortunes.

OFC articulates this critical perspective. It turns the stereotypical image of the soldier on its head. In OFC, the soldier is violent and authoritarian, but also critical, peaceful, and creative. Here, the soldier engages with the public on a direct level, and the soldier becomes the leading voice of dissent—reenacting war to end war.6

It presents the wars as ones that are fought by young Americans—enlistees in a military that former U.S. Marine Martin Smith describes as a “cross section of working class America . . . many of the country’s poor and poorly educated.”7 Moreover, it allows these same soldiers to speak out and openly critique the military in public. Reppenhagen states:

Being in the military, I felt oppressed and controlled by the government. I didn’t feel like I had a voice. I didn’t have the right to speak out, and now, I’m out here in the streets, doing something, taking control of my life, taking control of my country, taking control of my military and that is extremely empowering.8

Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW), DNC Demonstration, ca. 2008, Denver, pictured: Jeff Englehart (photographer unknown, courtesy of Aaron Hughes)

After Washington, DC, other mock patrols were staged by different chapters in other cities, including New York, Chicago, Seattle, Los Angeles, and Denver.

Hughes took part in a New York City patrol of Union Square, the subways, the former site of the World Trade Center, and Times Square. He described the Times Square action as a “real mess” because “we kind of got confused on who all the civilians were and we ended up pushing into some people that were real civilians. There was a moment of fear. Veterans are these young kids—eighteen and nineteen and we’re patrolling New York. We were forcing the public to make a lot of jumps in their understanding”9

A YouTube video of the action attests to the chaos that was created. People in the streets scream as IVAW members rush into the crowd and begin detaining people. Some people try to help but are pushed to the side. Others in the crowd freeze and put up their hands so they won’t be shot. Around them, the blinking lights, billboards, and television monitors of Times Square adds to the surreal nature of the scene.

For the veterans, the performance verged too close to reality, too close to an actual patrol. Hughes recalls:

It would click in your head that there was this anger—you stop seeing Americans for a moment. You just see these people that you’re angry with. It’s just this idea of dehumanizing them to the point where there’s anxiety.

Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW), Operation First Casualty, unknown date, San Francisco; pictured left: Steven Funk (photographer unknown, courtesy of Aaron Hughes)

You want to knock them over. You want to pull the trigger. It’s part of the whole mentality. That whole military training came back for a lot of us, and trying to process that back through was really hard.10

He adds:

I think we were performing something that we didn’t want to be anymore, and that’s a lot of [the] reason why that action was so powerful, and why we couldn’t keep doing it, why it wasn’t sustainable. It was literally destroying our membership in some ways.11

OFC continued to force the public to deal with the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, conflicts that were out of sight and out of mind for most Americans. Hughes asserts that OFC forces people to choose a position. “Depoliticalization is all about not having to choose,” he says. “Not having to deal with conflict. Not having to have a position. Creative work changes that. It forces people to deal with war.”12

From Uniform to Pulp, Battlefield to Workshop, Warrior to Artist

“We all have the ability to do something. We can push back.”

—Drew Cameron13

Creative resistance as personal and political action is also at the center of the Combat Paper Project by IVAW member Drew Cameron and artist Drew Matott. Cameron was deployed to Iraq in 2003 and served in the 75th artillery. In 2007, three years removed from active duty, Cameron put on his uniform outside his home in Burlington, Vermont, and asked a friend to take photographs of him cutting it off with a pair of scissors. He recalls, “My heart started beating fast. It felt both wrong and liberating. I started ripping it off. The purpose was to make a complete transformation.”14 His action provided the impetus for the Combat Paper Project. Cameron teamed up with Matott at the Green Door Studio in Burlington and learned the art of papermaking, and then they shared this process with the veteran community.

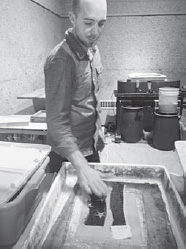

The Combat Paper workshops involve veterans shredding their uniforms into small pieces, mixing them with water, and pulping them. The pulp can then be made into sheets of paper for veterans to use for printmaking and personal journals. The process becomes a form of therapy, and the art a means to generate a larger conversation with the public about the reality of combat in Iraq and Afghanistan. Cameron explains:

The story of the fiber, the blood, sweat, and tears, the months of hardship and brutal violence are held within those old uniforms. The uniforms often become inhabitants of closets or boxes in the attic. Reclaiming that association of subordination, of warfare and service into something collective and beautiful is our inspiration.15

To reach other veterans, Cameron and Matott held workshops in Burlington, and then took the workshops on the road and traveled extensively throughout the United States and abroad. They met with other veterans from the Iraq War, Afghanistan War, Gulf War, Bosnian War, Vietnam War, World War II, and the Korean War, who subsequently turned their uniforms into paper and personal expressions.

Combat Paper Project, workshop in Milwaukee, pictured: Drew Cameron, ca. March 2013 (author photograph)

For participants, the act was one of release. Eli Wright, who served as an Army medic, explains, “This project saves lives, it gives us direction—to find we can build bridges and tear down those walls and remake sense of our lives.”16 Donna Perdue, a Marine Corps veteran, states, “Most of the therapy actually comes while shredding the uniform. During this time, participants are cutting small 1″ pieces that make it easier for the beater to turn it into pulp later, and honestly, memories are being triggered . . . People start talking quietly at first, and then the floodgates open.”17

Drew Cameron, You Are Not My Enemy, ca. 2012 (author photograph)

Jennifer Pacanowski, an Army medic who served in Iraq from 2004 to 2005 and was later diagnosed with PTSD, recalled, “I just started cutting my uniform up, and before I knew it, I was sweating and my hand was bleeding. It was so satisfying. I can’t even describe it . . . like just destroying a really bad memory.”18 Leonard Shelton, a forty-four-year-old Marine Corps veteran who served for twenty years, adds:

I was in the process of throwing the [uniforms] out when I learned about this [the Combat Paper Project] and thought, I want to make paper out of this so I can write on it. I remember standing in front of the mirror when I got out and saying, who are you? I didn’t know. They [the military] told me where to go. They told me what to eat. They told me to cut my hair every two weeks.19

Shelton fought in the first Gulf War, and was diagnosed with PTSD just before he was to be shipped out to Iraq in 2003. He retired from the Marines in 2005 and now receives a check for $207 a month.20

Other veterans had similar reactions. Jason Hurd, a Tennessee National Guard veteran who served in Iraq in 2004 and 2005, stated:

When you hold these strips in your hand, you think about all the times you ironed it and spit polished your boots—all that was something the Army made you do. This is my uniform now. I’m not Army property anymore, and neither is it.21

The images that veterans put on paper are as intense as the reasons for making the work, and the paper itself.

Jon Michael Turner created a silhouette image from the dog tag of his friend who was killed in action in Iraq. Eli Wright created Open Wound—red ink splashed on paper with a hole torn in the center as if the paper were a body. Cameron’s initial images were screen prints of photographs of him taking off his own uniform and included a poem entitled “You are not my enemy”—a message to the Iraqi people. Another print by Cameron shows a soldier and the U.S. Army logo. The text reads, “There’s Wrong and Then There’s Army Wrong: Resist Today”—a takeoff on the “Army Strong” campaign that helped recruit so many young men and women into the military. Cameron then littered the print with gunshots.

Other participants were less critical of the military. Zach Choate, a veteran who served as a gunner in the 10th Mountain Division, stated, “I’m hoping I come out of this a little more whole, a little more at peace. I’m not an anti-war, anti-military person. This is just me fixing me.”22 Choate adds that the project has provided him with a sense of community, helping him find other veterans to talk with and share experiences. “Each one of these guys I meet along the way, they’re like family now. It’s already helping. I’m starting to get the good feeling.”23 Aaron Hughes concludes, “War is such a destructive force. A part of the healing process, or a part of transforming out of that person who was part of that destructive process, is doing things that are creative—producing culture and finding a way to tell stories that are constructive instead of destructive.”24