Impersonating Utopia and Dystopia

ON DECEMBER 3, 2004, on the twentieth anniversary of the Bhopal disaster, a spokesperson for Dow Chemical, “Jude Finisterra,” appeared on BBC World Television and made a stunning announcement. Dow Chemical, which had acquired Union Carbide in 2001, was going to take full responsibility for the 1984 chemical plant disaster in Bhopal, India—a disaster that had claimed approximately twenty thousand lives and made hundreds of thousands of people sick. Dow would immediately liquidate Union Carbide, worth $12 billion, and use the funds to compensate the victims and clean up the site because it was “the right thing to do.” Finisterra also promised to push for the extradition of Warren Anderson, the former Union Carbide CEO who had fled India to the United States in 1984 after being charged on multiple counts of homicide.

The five-and-a-half-minute announcement to millions of listeners aired twice on the BBC, became the top story on Google News, and was further circulated by Reuters and other press agencies. The incredible news was met with jubilation in Bhopal and cheered around the world. In the financial sector, the announcement was met with condemnation. Dow’s stock dropped by $2 billion on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange within a twenty-minute time span.

The only problem with the announcement was that “Jude Finisterra” was not a Dow spokesperson; he was a member of the Yes Men. The announcement was a hoax. Or, from the Yes Men’s perspective, it was “an honest representation of what Dow should be doing.”1

The Yes Men, BBC Bhopal announcement, December 3, 2004 (Yes Men)

In one fell swoop the Yes Men, two activist artists—Igor Vamos (Mike Bonanno) and Jacques Servin (Andy Bichlbaum)—turned a major corporation, a leading media network, and the Frankfurt Stock Exchange upside down by presenting the news that they wished to hear. They simultaneously caused a public-relations nightmare for Dow and brought renewed global attention to the Bhopal disaster, considered by many to be the worst industrial accident in history.

Beyond Laughter

The Dow stunt followed the typical Yes Men blueprint for success. They created a fake website that closely resembled an official website of a corporation or government agency, including is a contact e-mail that media outlets or convention organizers inadvertently believed to be valid. They were then contacted with an invitation to speak. Next, the Yes Men arrived, pretending to be official company representatives, and then espoused positions and proposals that countered the official line—either being complete parodies of the corporation at its absolute worst or a move in a new direction toward social justice, which if real, would threaten the company’s bottom line. Finally, the Yes Men broadcast the stunt far and wide through their own press releases and video, making a small private gathering a major public spectacle.2

In the case of the Dow stunt, the Yes Men presented their dream scenario. The BBC unwittingly contacted the Yes Men through the mock website that they had set up called Dowethics.com and invited them to make a statement at the BBC Paris studio. “Jude Finisterra” (Jude, the patron saint of lost causes; and Finisterra, “the end of the world”) arrived and delivered the good news.

Union Carbide had in actuality made minimal payments to the victims of the disaster, and Dow had ignored the Bhopal issue after it had acquired Union Carbide. Mike Bonanno of the Yes Men explains, “The people of Bhopal have been trying for 20 years to get someone to listen. It was less about it being funny and more about being the only kind of action we could think of that would get into the media.”3 He adds, “Typically, we haven’t been in the business of suggesting alternatives. In the case of the Dow statement, Andy [Bichlbaum] did suggest an alternative—paying out $12 billion in damages. That is exactly what Dow should do. Of course, everyone applauded and agreed with it—except Dow.”4

Mike Bonanno and Andy Bichlbaum of the Yes Men (Yes Men)

Dow contacted the BBC once it caught wind of what had transpired and demanded a retraction of the story, which the BBC did, albeit two hours after the initial interview was given. Nonetheless, the damage was done. The hoax became the leading global news story of the day and more than six hundred articles about it were published in the U.S. press alone.5 The Bhopal catastrophe was placed into the public spotlight and, more important, Dow’s unwillingness to come to the aid of the people of Bhopal was made clear by its comments following the discovery of the hoax. Dow stated that they were not responsible for the Bhopal accident, and would not commit financial resources to addressing the disaster. To reassert Dow’s position, the Yes Men sent out another press release pretending once again to be Dow. The statement was picked up by some news organizations as fact, and read, in part:

Dow shareholders will see NO losses, because Dow’s policy towards Bhopal HAS NOT CHANGED. Much as we at Dow may care, as human beings, about the victims of the Bhopal catastrophe, we must reiterate that Dow’s sole and unique responsibility is to its shareholders, and Dow CANNOT do anything that goes against its bottom line unless forced to by law.6

In the aftermath of the stunt, the corporate media blasted the Yes Men for playing a cruel hoax on the BBC and Dow, and for falsely raising the hopes of the people of Bhopal. The Yes Men countered:

What’s an hour of false hope to 20 years of unrealized ones? If it works, this could focus a great deal of media attention on the issue, especially in the US, where the Bhopal anniversary has often gone completely unnoticed. Who knows—it could even somehow force Dow’s hand.7

The Yes Men also traveled to Bhopal and met with activists who appreciated how much they had raised awareness of the issue. The Yes Men add:

After all, the real hoax here is Dow’s claim that they can’t do anything to help. They have conned the world into thinking they can’t end the crisis, when in fact it would be quite simple. What would it cost to clean up the Bhopal plant site, which continues to poison the water people drink, causing an estimated one death per day? We decide to show how another world is possible, and to direct any questions about false hopes for justice in Bhopal directly to Dow.8

The Yes Men’s action revealed not just the negligence of Union Carbide and Dow, but the fact that the market would punish Dow for being socially and environmentally responsible. David Darts and Kevin Tavin write:

The Yes Men’s performance clearly exposed the tenuous relationship between corporate responsibility and free-market capitalism. By appearing to be doing the right thing for the victims and people living in Bhopal, the Yes Men demonstrated that Dow would clearly be doing the wrong thing for its bottom line. The hoax thus illustrated the severe limitations of corporate social responsibility within an unregulated free-market system.9

After the BBC retracted the story, Dow’s stock regained what it had lost. The stunt also addressed the shortcomings of the corporate media. If the Yes Men could get access to the BBC—one of the most respected news outlets in the world—one must assume that governments and corporations have had little trouble in consistently manipulating the media. This was exemplified by the George W. Bush administration’s infamous claim that Iraq possessed “weapons of mass destruction”—a claim that many media outlets reported as fact.

In the Dow stunt, the Yes Men exposed just how easy it is to have fiction pass as fact. Bichlbaum explains, “It’s an issue of time. There are so many stations with so few journalists that they cannot possibly verify all of their sources. That’s how corporate press releases end up parading as news.”10 But the Yes Men’s manipulation of the media did attract serious criticism. Kelly McBride, ethics group leader at the Poynter Institute, a nonprofit school for professional journalism contended that, “It makes the public dubious of real reporters. It makes it appear as if reporters are acting in collusion with various agencies.”11 McBride, however, misses the obvious. The corporate media does often act in collusion; they routinely line up in droves at White House and Pentagon press briefings and reiterate the viewpoints of those in power, often verbatim, and either ignore, or greatly marginalize, oppositional voices.

The Yes Men’s decision to subvert the BBC was a tactical decision to reach the largest audience possible. Many activist artists are confined by their venue—often the gallery, museum, or the artist’s own website. The Yes Men were not. They literally reached the same audience as the BBC. Moreover, the brilliance of the stunt was that the Yes Men employed the same tactics as corporations (public-relations campaigns and press releases), while working to undermine them. Naomi Klein writes that, “The most significant culture jams are not stand-alone ad parodies but interceptions—counter-messages that hack into a corporation’s own method of communication to send a message starkly at odds with the one that was intended.”12 The Yes Men accomplished this with the Dow hoax, and in doing so, raised the bar for interventionist art and culture jamming.

![]()

Much of what passes for culture jamming is known as adbusting—where an individual artist or designer creates a fake advertisement or logo in order to subvert the original image and its message. The Vancouver-based magazine Adbusters epitomizes this practice, as does the practice of billboard alteration. But reworked images and the individualism that is often associated with contemporary culture jamming is often divorced from its political roots.

Culture jamming, adbusting, shop dropping, and interventionist art have all been influenced, directly or indirectly, by the Situationist International (SI), a loose international movement of artists and activists who employed creative resistance during the late 1950s and 1960s. Guy Debord, who wrote the seminal Situationist text The Society of the Spectacle, argued that capitalism had become so advanced, and so all-encompassing, that workers could not envision any other political or social reality. Worse, workers had become complicit in their own subjugation. Entertainment, advertisements, and consumer culture presented a fake reality (a spectacle) in order to mask how capitalism degrades human life. The SI encouraged people to subvert the spectacle—to turn it on its head, and to alter its meaning.

However, many contemporary artists forget or choose to ignore SI’s anticapitalist politics. Individual culture jamming and adbusting makes people think and often laugh, but rarely does it pose much of a threat to the corporation that it parodies. SI, in contrast, was part of the international socialist movement; during the May 1968 uprisings in Paris, SI supported the wildcat strikes and the workers’ councils that were organized when people took over schools and factories. This approach differs from a lone artist who creates a mock ad and posts it on a website. The Yes Men’s practice goes beyond adbusting. Their work, while still primarily rooted in the realm of the symbolic, uses parody and hoaxes to work in conjunction with the struggles of the movements that they are associated with—often the antiglobalization movement and various environmental-justice movements. Many of their actions take place during larger demonstrations, and have been in collaboration with the Rainforest Action Network and Greenpeace. Others have taken place in conjunction with international days of action designed to mobilize people around climate-change issues, including campaigns by 350.org and the Mobilization for Climate Justice.

SurvivaBalls

The Yes Men have also turned their attention to the largest of all environmental disasters—global warming—targeting the corporate and governmental leaders who have undermined efforts to regulate greenhouse-gas emissions. In 2006, the Yes Men unleashed the “SurvivaBall” at the Catastrophic Loss conference for insurance companies at the Ritz-Carlton hotel in Amelia Island, Florida, pretending to be employees of the oil-services giant Halliburton.

And unlike the Dow announcement, the Yes Men this time presented themselves as Halliburton at their dystopian worst. Halliburton’s “representative,” whom they named Fred Wolf, presented a SurvivaBall informational video while three conference attendees modeled giant white orb outfits that Wolf describes as a “gated community for one.”13

Wolf explained that with the outfits, corporate managers would be able to survive anything that “Mother nature throws his or her way.”14 Global warming? Floods? Hurricanes? Rising sea level? No problem, as long as one is inside a SurvivaBall. The outfits supposedly contained communication devices, weapons to fend off attacks, medical equipment, nutrient-gathering devices, and an appendage to stick into an unsuspecting animal to draw power from it. Wolf explained that:

The SurvivaBall builds on Halliburton’s reputation as a disaster and conflict industry innovator. Just as the Black Plague led to the Renaissance and the Great Deluge gave Noah a monopoly of the animals, so tomorrow’s catastrophes could well lead to good—and industry must be ready to seize that good.15

The Yes Men, SurvivaBall, Catastrophic Loss Conference, Amelia Island, Florida, 2006 (Yes Men)

One would have hoped that the conference attendees would see through the prank (considering how bombastic it was), but the opposite occurred. People asked detailed questions (primarily about the SurvivaBall cost feasibility and defense abilities against terrorist threats) and requested business cards.

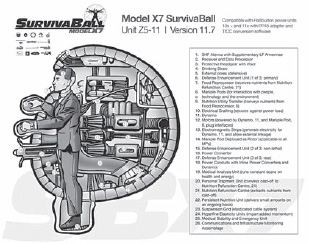

The Yes Men, SurvivaBall, diagram (Yes Men)

The audience response provided little confidence that individuals who subscribe to the logic of corporate capitalism will ever embrace meaningful solutions that will significantly curb climate change, especially if profit motives are at stake. If anything, the Yes Men helped draw connections to how the oil and gas industries have lobbied extensively against regulations that would curb greenhouse gas emissions.16

The Yes Men have unleashed SurvivaBalls in protest demonstrations throughout the country in their campaign, appropriately titled, Balls Across America. One action took the form of an attempted waterborne assault on the United Nations Building in New York. On September 22, 2009, twenty-one SurvivaBalls gathered on the banks of the East River to “blockade the negotiations and refuse to let world leaders leave the room until they’d agreed on sweeping cuts in greenhouse gas emissions, as Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon has demanded.”17 Yes Man Andy Bichlbaum described the event as a “scenic and mediagenic way to call attention to what our leaders need to do in the run-up to the U.N. Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen.”18

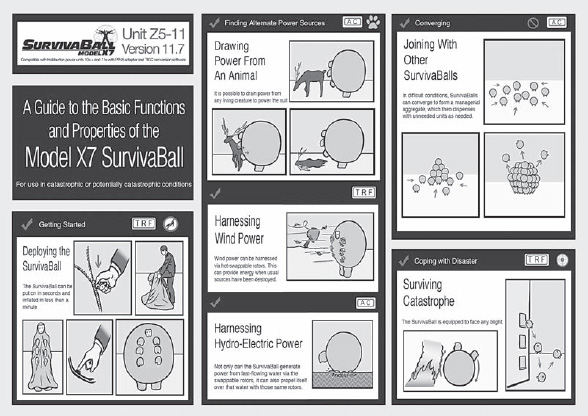

The Yes Men, SurvivaBall, diagram (Yes Men)

Police swarmed in by land, boat, and helicopter as activists dressed in SurvivaBalls waded in the water. Seven people were charged with trespassing, and Bichlbaum was handcuffed and taken to jail. His arrest was given prime-time media coverage by CNN. Bichlbaum stated:

That’s the whole point of civil disobedience. Thanks to my momentary discomfort, our symbol of the stupidity of not taking action on climate change was seen by tens of millions of people. It all worked out great, and I remain grateful to the NYPD for having accidentally made our event successful beyond our wildest dreams.19

The media coverage resulting from the arrest conjures past activist tactics of the woman’s suffrage movement, the civil rights movement, and various labor struggles, all of which used representations of police arrests and abuse to their advantage. The Yes Men are part of this tradition of civil disobedience. Mike Bonanno states, “With ‘Balls Across America,’ our goal is to get arrested fair and square, all across this fair land of ours. It’s a great way to get attention for a crucial issue.”20

The Yes Men, SurvivaBalls storming the U.N. Building, New York City (Yes Men)

The Yes Men assert that their practice of impersonating and embarrassing corporations, administrations, and government agencies is not an end in itself. It is part of a broader movement, and part of a lineage of artists who agitate for change through creative and collaborative means.