Denise Scott Brown, 1967.

Courtesy of VSBA

Denise Scott Brown, one of the world’s foremost women architects, was born to Phyllis Hepker, a free spirit who spent her childhood in the African wilderness.

Phyllis and her brothers were homeschooled by a governess. They read stories, learned natural history and care of animals in the veld (African grassland) and on the farm, and made musical instruments and toys from materials at hand around them. Later, when the teenage Phyllis went to boarding school, she found sympathetic teachers who allowed her to do her homework, as she was accustomed, up a tree.

Phyllis entered architecture school in South Africa in 1928, but she returned home to Zambia after two years to help her parents run the family hotel. Phyllis’s parents—originally Jewish emigrants from Latvia—settled in Zambia at the turn of the 20th century when it was still lion country. While working at the hotel, Phyllis met and married Shim Lakofski, a young South African of Lithuanian Jewish origin, and they made a home in the mining town of Nkana. Phyllis gave birth to Denise on October 3, 1931. But when Denise fell ill, possibly with malaria, the couple decided to raise their family in Johannesburg.

The family eventually grew to include two sisters and a brother for Denise. Phyllis shared her passions for reading, nature, and “making things” (including traps for anteaters), with her children. She also imparted her enthusiasm for modern architecture and her love of the flat-roofed house with big windows that was designed for her family by three of her former architecture classmates.

At four years old, Denise knew she wanted to be an architect like her mom. But at six, she changed her mind: her new aim was to teach children like her grade school teacher. Denise was not only the youngest and smallest in her class, but she was also marked as “clever,” and was one of just a few Jewish children there. Despite feeling like an outsider, Denise took pleasure from working with her hands and learning in action at her elementary school. By age 12, English and art were her favorite subjects, and Denise considered pursuing a career in linguistics or writing. But a perceptive family friend suggested research might be a better career path for her, noting, “You ask so many questions.”

In high school, Denise joined an archeological club and excavated for Stone Age implements. Here, adults opened her eyes to life beyond school, and when a member recommended she reconsider architecture, Denise returned to her mother’s field. The decision, made “without too very much knowledge,” has lasted a lifetime.

In 1948, Denise followed her mother into the University of the Witwatersrand, “Wits,” in Johannesburg. But before starting architecture, she spent a year delving further into English, French, and psychology. In 1949, her first day in architecture brought a surprise: “There were all these men around, and I thought, ‘What are they doing here?’” Denise had known only women architects and concluded that it was women’s work. One of the men in her studio, Robert Scott Brown, would later become her husband.

“There were all these men around, and I thought, ‘What are they doing here?’”

The architecture program included a yearlong internship in an architect’s office, and Denise decided to spend it overseas. In 1952, she began interning in London but in parallel took the entrance exam for a school there, the Architectural Association. When admitted, she transferred there. Although it meant two more years away from Robert, fate, she felt, was pushing her. After graduating, he joined her, and they married in London on July 21, 1955.

In South Africa, Denise had been drawn to African folk art that was influenced by Western culture, especially pop culture. When she and Robert traveled for their studies, they photographed architecture across Africa, Europe, the Middle East, and America. All the while, into their collection crept everyday objects and landscapes that testified to their growing fascination with pop culture. As postgraduates, their desire for travel grew more intense. Their 1955 honeymoon was a hitchhiking trip through Yugoslavia. In 1956, they crisscrossed France, Italy, Holland, and Germany, attended summer school in Venice, and worked in Rome for the architect Giuseppe Vaccaro. The couple camped, hiked, and traveled by cheap trains and old cars. For Denise, this was the best preparation possible for the global work she eventually undertook. And she still uses the photographs she took along the way.

Back in South Africa, the Scott Browns planned their further education. Where was the knowledge of urbanism—the way of life of city dwellers—to be found that they felt was needed to practice architecture and site planning in Africa? A respected London teacher recommended the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, where architect Louis Kahn taught. So in 1958, they entered Penn’s city planning school, just as the civil rights movement was bringing excitement and urgency to cities and intellectual ferment to Penn.

Robert and Denise were accustomed to learning during the tumult of South Africa under apartheid and Europe after World War II, but the American turmoil seemed familiar to them. Their travels had raised questions, particularly about urban life. They found that modernism was not addressing the needs of social life and urban blight / city decay. Now Penn offered the prospect of discovering methods to approach and reframe their questions. They spent a year in the most exciting intellectual environment they had known, while social unrest and burning issues heightened the quality of their educations.

Then, while on a Sunday drive in June 1959, a car in rural Pennsylvania ran a stop sign and hit the couple. Robert died in the ambulance.

Denise flew home, in deep sorrow for her personal loss but mourning, too, the tragedy of Robert’s lost potential to help revitalize South Africa’s architecture. But Denise overcame her devastation and returned to Penn in the fall, where she received her master’s degree in city planning (1960) and architecture (1965), and became a professor. She had also, without knowing it, left South Africa for good.

In 1960, Penn hired Denise to teach studio classes in urban design and city planning, which involved hands-on instruction with the students. Moving from student to teacher seemed a big step, but, she recalls, “If I had any pangs or stage fright, they didn’t last more than 20 minutes. I realized that I was born to do this.” The next year, courses in theory of architecture and planning were added to her duties.

Denise’s new professorial role brought Robert Venturi into her life. In 1960, she and “Bob” met at a faculty meeting. When the idea of demolishing Frank Furness’s Fine Arts Library was brought up, Denise protested that this would be “a huge mistake.” She tells how, after the meeting, Robert came up and explained that he agreed with everything she said. Although happy to hear this, she replied, “Well, then, why didn’t you say something?”

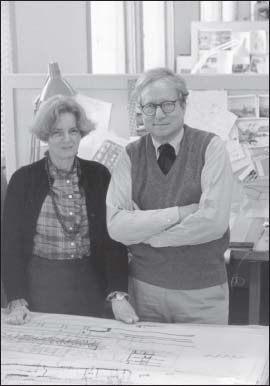

Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi in 1985.

Courtesy of VSBA

She and Bob formed a friendship based on shared enthusiasms in architecture. For several years they taught a course together and occasionally collaborated professionally. “When asked,” Denise recalls, “I would go into Bob’s office to give crits [critiques] of his architecture firm’s work and he would visit my studio class in the evening to do the same.” He would critique her students’ work.

From 1960 to 1967, Denise taught at University of Pennsylvania; University of California, Berkeley; and University of California in Los Angeles (UCLA). Her focus was studio, the spine of architectural education, where students “make things” and “learn by doing”—where they design. To Denise, it was familiar territory, but she introduced innovations adapted from planning studios and added urban subject matter relating to popular culture, land economics, and social life. She believed the people and the atmosphere were important aspects of the architecture.

In 1966, having decided that her next studio would be centered on Las Vegas, Denise invited Bob to visit the city with her and to lecture at UCLA. Bob says, “First I fell in love with Las Vegas. Then I fell in love with Denise.” They were married in Santa Monica, California, on July 23, 1967, and returned to Philadelphia where Denise joined Bob’s firm. For the next 40 years they worked together.

Early on, Denise and Bob combined building their architecture practice and teaching. At Yale, their studios, including “Learning from Las Vegas” (1968) and “Learning from Levittown” (1971), employed both traditional architecture and planning studio methods, but their subject matter derived from the idea that “low art” sources—advertising signs, parking lots, roadside strips, and suburban tracts, the “urban sprawl” of the 1960s—could offer architects valuable lessons in design. Students pursued their ideas through architecture and its theories but turned as well to urban planning, media studies, pop art, and the social sciences.

Another architectural partnership involved Anne Tyng and Louis Kahn. Anne, an architectural visionary, theorist, and teacher, was among the first women to receive a master’s of architecture from Harvard University. Fascinated by complex shapes, Anne designed and developed the Tyng Toy, a set of interlocking plywood shapes that children could assemble and reassemble. In 1945, at age 25, she worked with Louis Kahn, and her geometric ideas were employed in the design of the Trenton Bath House and Yale University Art Gallery, among other projects. In 1953, Anne became pregnant with Kahn’s child, and moved to Rome to avoid a scandal since he was a married man. In a letter to Kahn from Italy, Anne wrote, “I believe our creative work together deepened our relationship and the relationship enlarged our creativity. In our years of working together toward a goal outside ourselves, believing profoundly in each other’s abilities helped us to believe in ourselves.” The relationship ended in 1960 when he became involved with another woman. After 1968, Anne focused her attention on research, earning a doctoral degree from the University of Pennsylvania, where she taught for almost 30 years.

In 1972, along with fellow architect Steven Izenour, Bob and Denise published Learning from Las Vegas, which is considered one of the most influential architectural theory books of the 20th century. The book has been read by generations of architects, and its content and methods remain models for architectural research and teaching. Over the decades, Bob and Denise extended and developed the book’s themes in their practice. Through their work, they crossed the world, covered wide terrains of thought regarding architecture, art, and social issues, and built many types of projects.

Denise Scott Brown in the Las Vegas desert, with the Strip in the background, 1966.

Courtesy of Robert Venturi

As principals of their firm, they led teams in the conceptual design, design development, and production of projects such as the Conseil Général Building in Toulouse, France, and the addition to the British National Gallery on Trafalgar Square in London. Denise is proud of her role as a designer on the office’s major architectural projects, but she is also happy to have worked as an advocate planner for low-income communities threatened by an expressway in Philadelphia, and on plans and designs for the University of Pennsylvania, Dartmouth College, and the University of Michigan. Her work for these campuses involved first campus master and area planning and then design of important complexes within her plans: the Perelman Quadrangle at the University of Pennsylvania, Baker-Berry Library at Dartmouth, and the Palmer Drive Life Sciences Complex at the University of Michigan.

Denise has learned to stay involved down to the details of door hinges, to ensure that important projects’ goals are maintained in the development of her designs. She loves to watch the completed buildings and open spaces in use and is delighted when people discover opportunities that she provided.

“It’s like producing a jungle gym for grown-ups,” she said. “We build it so that they can explore it, go where they want. Spaces can be used in many ways.” Before one complex was completed, students discovered a shortcut across it that she had planned. She was thrilled when they broke down the construction fences to ride their bicycles along it. “There’s nothing better,” she said.

But Denise’s life as a woman in architecture has been difficult. An article titled “Room at the Top? Sexism and the Star System in Architecture” recounts her early experience in the field:

The social trivia … “wives’ dinners” … job interviews where the presence of the “architect’s wife” distressed the board; dinners I must not attend because an influential member of the client group wants “the architect” as her date; Italian journalists who ignore Bob’s request that they address me because I understand more Italian than he does; the tunnel vision of students toward Bob, the “so you’re the architect!” to Bob, and the well-meant “so you’re an architect too?” to me.

Established in 1979 by the Pritzker family of Chicago through their Hyatt Foundation, this international prize is awarded each year to a living architect for contributions to humanity and the built environment through the art of architecture. Considered the Nobel Prize of architecture and the profession’s highest honor, the honoree receives $100,000 and a bronze medallion.

In 1991, Bob received the Pritzker Prize for his body of architectural work, while Denise stayed home. It hurt them both that the committee didn’t acknowledge their 25-year partnership. Bob has been vocal in objecting when she is omitted, and slowly Denise has found support and her own rewards.

“I’ve always had an oscillation between breadth and focus. And it’s been a good one for me professionally, although it means it’s very difficult to define me.”

“I have been helped,” she said, “by noticing that the scholars whose work we most respect, the clients whose projects intrigue us, and the patrons whose friendship inspires us, have no problem in understanding my role. They are the sophisticates. Partly through them I gain heart and realize that, over the last 20 years, I have managed to do my work and, despite some sliding, to achieve my own self-respect.”

Looking back on her aims and interests as a child, Denise found that during her career in architecture she had achieved most of them; in fact, “those things and a few more, because I had also become an urban planner. I had become very interested in the social sciences, as well. But they said to me at high school that my talents were very broad and I’d have to learn to focus. And the truth is, I’ve always had an oscillation between breadth and focus. And it’s been a good one for me professionally, although it means it’s very difficult to define me.”

Robert announced his retirement in 2012, while Denise continues to lecture, write, and go into the office, still on Main Street in Manayunk, Philadelphia, about once a week.

LEARN MQRE

Einstein’s Wife: Work and Marriage in the Lives of Five Great Twentieth-Century Women by Andrea Gabor (Penguin, 1995)

Fuse: In, Re, De, Pro, Con (2012 video interview with Denise Scott Brown on her 81st birthday, in conversation with Amale Andraos, Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, Felix Burrichter), www.youtube.com/watch?v=X_-6KKw0SUg

Having Words by Denise Scott Brown (Architectural Association Publications, 2009)