Ellen Biddle Shipman in Boston, circa 1890.

Courtesy of Judith B. Tankard, Nancy Angell Streeter Collection

It’s rather surprising that Ellen McGowan Biddle, raised in the Wild West during the 1870s, would eventually be referred to as the “Dean of American Landscape Architecture.”

Ellen’s father, Colonel James Biddle, was a career military man who fought in the Civil War. Ellen’s mother was Ellen Fish McGowen, whose father, John McGowen, was the captain of a Union merchant ship and was in command of the ship when it fired the first shots of the Civil War.

After the Civil War, Colonel Biddle, Ellen, and their two sons, 14-month-old Jack and two-month-old David, moved wherever Colonel Biddle was stationed: first Macon, Georgia, then military outposts in Mobile, Alabama, then 250 miles upriver to Natchez, Mississippi. After eventually settling in Brenham, Texas, Ellen’s doctor felt that due to her stress and the hot climate, Ellen and the boys should return to her parents’ home in Philadelphia for the summer.

Baby Ellen, whom they called “Nellie,” was born on November 5, 1869. When Ellen and the boys and Nellie were well enough to travel again, they boarded a train for the seven-day trip from New York City to San Francisco. Colonel Biddle was stationed 500 miles from San Francisco in Camp Halleck, Nevada, where the family lived among the sagebrush for the next two years. The family was uprooted again, first to Fort Riley, Kansas, and then to Fort Lyon, Colorado, where Native Americans were then revolting against the US military’s presence.

One spring day, Ellen and the children set out into town to shop. Ellen stopped the mule-driven cart so that the children could pick the new buds that were peeking through the snow. After living in the sagebrush of the desert and then enduring months of snow, the children developed an appreciation for flowers that their mother helped foster. The children were delighted to gather the wildflowers, the verbena in all colors and the little forget-me-nots.

The East Coast newspapers were filled with stories of the Indian uprisings, so Ellen’s parents insisted that Ellen and the children return home. On the train ride back east, the children, by now thoroughly accustomed to life on the frontier, were awed by apple trees. Four-year-old Nellie, while passing a cemetery, exclaimed, “Oh! Mama, look at the beautiful stones growing out of there!” At their grandparents’ house, they saw their first cultivated garden.

After getting the boys settled at a Connecticut school in December 1875, Ellen and Nellie set off once again—this time to Arizona to rejoin the Colonel. At Fort Whipple in the Arizona territory, Nellie was fearless and strong. She rode horses, played marbles, flew kites, and gathered wildflowers with the other children at the outpost. In Arizona, the Biddle family added another baby boy, Nick, to the family.

When Nellie was 10, her uncle offered to take her back east with him. Her mother felt that it was time for her to attend school regularly and have the companionship of other girls. After the rough trip from Arizona to Los Angeles, where they rendezvoused, her mother wrote in her diary, “My brother said that the little one looked like a young Indian when he met her at Los Angeles, she was so sunburned, covered with dust and dirt, and the waist of her dress torn in shreds. She interested the passengers greatly, telling them of her life in Arizona and her travels.”

Back on the East Coast, Ellen, no longer called Nellie, was sent to one of the finest finishing schools, which was run by the granddaughter of Thomas Jefferson. Miss Sarah Randolph’s Patapsco Institute in Ellicott City, Maryland, was created not only to provide an excellent education but also to teach refined young ladies how to run a home. Classes consisted of basic housekeeping, sewing, and cooking along with mathematics, science, languages, painting, botany, philosophy, and psychology. The margins of Ellen’s notebooks were soon full of drawings of house and garden plans. Miss Sarah, noticing young Ellen’s passion, gave her an architectural dictionary as a history prize.

When Ellen turned 18, the Biddle family moved to Washington, DC, where the Colonel worked for the War Department. Ellen kept busy with the social scene in the nation’s capital. In her 20s, she shared a house in Massachusetts with friends and enrolled at Radcliffe College, then known as Harvard Annex. Ellen spent a lot of time with her housemate’s cousin, Louis Evan Shipman, a young playwright from a respectable New York family. Louis and Ellen married, moved to Connecticut, and welcomed a daughter the next year, named Ellen, like her mother.

“As I look back I realize it was at that moment that a garden became for me the most essential part of a home.”

The following year, Ellen and Louis moved to Cornish, New Hampshire, a celebrated summer resort town where many artists and writers lived. They found the little artists’ colony they shared with painters, sculptors, illustrators, writers, and musicians was perfect for the young couple. At a party the first night in Cornish, Ellen first realized her gardening passion. She reminisced years later, “Just a few feet below, where we stood upon a terrace, was a Sunken Garden with rows bathed in moonlight of white lilies standing as an altar for Ascutney. As I look back I realize it was at that moment that a garden became for me the most essential part of a home. But years of work had to intervene before I could put this belief, born that glorious night, into actual practice.”

The inhabitants of the artist colony created extraordinary gardens, and Cornish was described as “the most beautifully gardened village of all America.” Ellen designed her first garden there, a country garden with a dirt path lined with summer flowers, which was her model for many other designs.

In 1899, Ellen and Louis stayed in the home of Charles Platt and his wife while their own house was being built. Platt was a landscape painter when he first came to Cornish, but after a trip to Italy, he started designing landscapes and eventually homes incorporating Italian design elements. Ellen, in her spare time, created house plans on the drawing board in Platt’s studio. When Platt saw the drawings, he sent her a note that said, “If you can do as well as I was, you better keep on.” As encouragement, he gave Ellen her own drawing board and other tools of the trade, including a T-square for drawing straight lines, and drafting implements.

In 1903, Ellen and Louis purchased Brook Place, a 200-acre property where Ellen designed the architecture, interiors, and landscape. The property became her personal classroom. She explained later, “Working daily in my garden for fifteen years taught me to know plants, their habits and their needs.”

Ellen and Louis had two more children, Evan in 1904 and Mary in 1908. Ellen homeschooled her three children and loved it. Two years after Mary’s birth, however, Louis left the family and ran off to London. Now 41 years old and needing to support herself and her three children, Ellen looked to designing gardens and landscapes as a career.

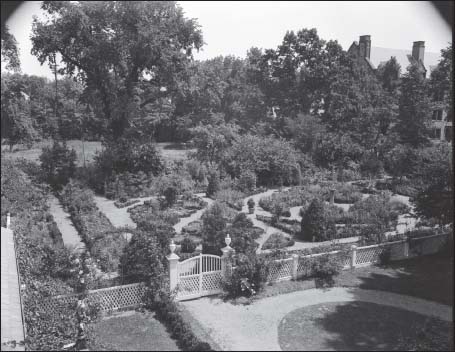

A garden Ellen designed for Henry W. Longfellow Place, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Library of Congress HABS MASS,9-CAMB,1-30

By that time, Ellen’s friend and longtime mentor Charles Platt had a successful business designing architecture and landscapes for the rich and famous from coast to coast. One day, Platt said to Ellen, “I like the outcome of your efforts at Brooks Place. Could you do the planting for the places I am building?” Ellen didn’t think that she was an expert at drafting, so Platt had one of his assistants instruct her on landscape drawing. After collaborating with Platt, Ellen soon developed a vast base of clients, creating construction plans for walls, pools, and small garden buildings and working on gardens and estates from New York and Ohio to Michigan and Washington.

In 1920, Ellen moved and opened her own design practice in New York City, where her younger brother Nick ran a successful law office. She purchased and remodeled a four-story townhouse on the corner of Beekman Place and East 50th Street. Her design offices were on the first floor, her home was on the second floor, and two apartments occupied the top two floors. Her townhouse became a place to show off her interior design talents, which soon became the main source of her income.

Ellen’s design practice grew through word of mouth, photos of her gardens in magazines, and associations with garden clubs, which were very popular in the early 20th century. Over the years, she had 24 clients in Greenwich, Connecticut; 17 in Mount Kisco, New York; 57 on Long Island; 44 in Grosse Point Shores, Michigan; and 45 in the Cleveland/Toledo, Ohio, area. Houston, Buffalo, and Winston-Salem, North Carolina, were also towns where Ellen had many clients. Ellen’s landscape designs graced the estates of captains of industry, financial leaders, and patrons of the arts, including the families of the Fords, Astors, and du Ponts.

Ellen Shipman in her Beekman Place office, New York, 1920s.

Courtesy of Judith B. Tankard, Nancy Angell Street Collection

Ellen hired only women designers, including Beatrix Far-rand, also based out of New York City. She mainly employed graduates from Lowthorpe School of Landscape Architecture for Women in Groton, Massachusetts. In the school catalog she is quoted, “There is no profession so suited to women, so needed and so repaying in every way—nor any that at once gives so much of health, wealth, and happiness.” When clients walked into Ellen’s design offices, they would catch a glimpse of girls in blue smocks bent over drafting boards.

A strong advocate for women, Ellen pointed out, “Before women took hold of the profession, landscape architects were doing cemetery work…. Until women took up landscaping, gardening in this country was at its lowest ebb. The renaissance of the art was due largely to the fact that women, instead of working over their board, used plants as if they were painting pictures, as an artist would. Today women are at the top of their profession.”

In 1921, House and Garden, House Beautiful, and several other magazines showcased Ellen’s gardens and popular collaborations with architects. House and Garden praised Ellen in 1933 as the “Dean of Women Landscape Architects.” During both world wars, Ellen was an outspoken advocate of the “victory garden.” To help in the war effort, families grew fruit, vegetable, and herb gardens for their personal use to help preserve food supplies for the troops. She offered the use of her New York office to the Garden Club of America so it could provide information about victory gardens to the nation.

In 1947, at the age of 78, Ellen closed her office and spent her retirement years living on the island of Bermuda, in a house that she designed. The property had views of both sides of the island and gardens running down the south slope. She died in her home on March 27, 1950.

LEARN MORE

The Garden Club of America: One Hundred Years of a Growing Legacy by William Seale (Smithsonian, 2013)

The Gardens of Ellen Biddle Shipman by Judith B. Tankard (Sagapress, 1996)

A Genius for Place: American Landscapes of the Country Place Era by Robin Karson (University of Massachusetts Press, 2007)