Marian Cruger Coffin, 1904.

Courtesy of the Winterthur Library: Winter Archives

For more than 53 years, Marian Coffin created the beautiful landscapes of our nation’s finest estates. Her design process, which she outlined in her book Trees and Scrubs for Landscape Effects, covered the entire property. She mastered the monumental task of creating landscapes for huge estates while sticking to her design philosophy: “Simplicity is beauty’s prime ingredient.”

Marian Cruger Coffin came from an illustrious East Coast family. She was born in Scarborough, a northern suburb of New York City, on September 27, 1876. Her mother, Alice Church Coffin, was a descendant of Richard Church, one of the passengers on the Mayflower. Her father, Julian Ravenel Coffin, had ancestors who settled the island of Nantucket. Marian’s great-great-uncle was the Revolutionary War-era painter John Trumbull, and her uncle Benjamin Church was an engineer who worked with Frederick Law Olmsted on the design of Central Park.

Marian’s parents were married in 1874, and Marian was born two years later. When she was seven, her father passed away of complications from malaria. The family was left with just $300 and so lived for several years with the sister of Marian’s mother, in Geneva, New York. Marian was a fragile child and went to public school for only a few months. Instead, she was privately tutored at home.

Marian’s mother, Alice, had high-society friends. When Alice’s best friend, Mary Foster, married Colonel Henry A. du Pont, Alice was a bridesmaid. The groom was a member of the du Pont dynasty, one of America’s richest and most prominent families in the 19th and 20th centuries. Marian grew up best friends with the du Pont children, Louise and Henry, and played with them on the du Pont estate, Winterthur.

In a 1932 letter Marian lamented, “I secretly cherished the idea of being a great artist … but that dream seemed in no way possible of realization…. My desire to create was strong, I did not seem to possess talent for music, writing, painting, or sculpture, at that time, the only outlet a woman had to express any artistic ability…. My artistic yearning lay fallow until I realized it was necessary to earn my living.”

When Marian was 16, her family moved just a few doors moved to Boston so that Marian could go to school. Realizing Marian’s quest to add art to her life and earn an income, an architect friend suggested that she try landscape architecture, a new field that was open to women. She entered the landscape architecture program at MIT in 1901, one of only two female students in the program. She said, “You can imagine how terrifying such an institution as ‘Tech’ appeared to a young woman who had never gone more than a few months to a regular school, and when it was reluctantly dragged from me that I had had only a smattering of algebra and hardly knew the meaning of the word ‘geometry’ the authorities turned from me in calm contempt.”

Evidently, the private tutoring that she received during most of her childhood had not prepared Marian for advanced math concepts. “I was told that I was totally unprepared to take the course and refused admittance. It was owing to his [Professor Chandler’s] kindness and also to Professor Sargent’s and Mr. Lowell’s encouragement that I persevered and was able by intensive tutoring in mathematics to be admitted as a ‘special’ student in Landscape Architecture, taking all the technical studies and combining the first two years in one so that I finished in three years.”

Martha Brookes Hutcheson was one year ahead of Marian Cruger Coffin in the landscape architecture program at MIT. Martha’s interest in landscape architecture was motivated by a visit to a hospital. She recalled, “One day I saw the grounds of Bellevue Hospital in New York, on which nothing was planted, and was overcome with the terrible waste of opportunity for beauty which was not being given to the hundreds of patients who could see it or go to it, in convalescence.” In 1935, Martha was the third woman to be named a fellow in the American Society of Landscape Architects.

Marian graduated as a special student in the class of 1904, one of a handful of women to finish the program before it was closed a few years later. Her old friend Henry du Pont studied horticulture at Harvard while Marian was at MIT. They shared a love of plants. For a Christmas gift in 1902, Henry sent Marian the four-volume set of The Cyclopedia of American Horticulture by Liberty Bailey. Marian wrote to Henry, “My dear Harry, Bailey arrived Friday night to my great joy. I immediately sat down on the floor and hugged all three volumes at once!” The fourth volume was on its way, not yet delivered.

After graduation, Henry and Marian—accompanied by Marian’s mother—traveled to England, Europe, and the Dalmatian Coast on the Adriatic Sea to tour gardens. Upon their return to the States, mother and daughter moved to New York City. Finding no jobs available for women landscape designers, Marian opened her own design office out of their home at the National Arts Club. Marian’s first commission on record was for the Sprague Estate in Flushing, New York. She described her client-centered design process in a Country Life in America article, saying, “In taking up the problem the first step was to ascertain the wishes of the owners…. The design must be in scale not only with the house and the grounds but also with the means and taste of the owner.”

She soon received the commission for the 3,000-acre Oxmoor Farm and estate in Louisville, Kentucky. As Marian’s reputation grew, she began designing estates all around New England. Marian was made a junior member of the American Society of Landscape Architects in 1906, joining the two other women members, Beatrix Farrand and Elizabeth Bullard.

In 1902, Henry du Pont and his father started renovations on the Winterthur mansion and estate—2,400 acres, including 60 acres of naturalistic garden. Henry and Marian’s friendship turned to business in 1910 when Henry asked Marian to help him with the landscape architecture on the property. In one correspondence, she wrote, “My dear Harry, this letter is a mixture of friendship and business, so in respect to the latter I will write you on the typewriter and save your eyesight.”

The du Ponts had a long history of studying plants. “Botaniste” was the profession given on Éleuthère Irénée du Pont’s passport when he came to America in 1801 and founded the du Pont empire. Louise du Pont, Henry’s sister, said, “Father would take Harry and me by the hand and walk through the gardens with us, and if we couldn’t identify the flowers and plants by their botanical names, we were sent to bed without our suppers.”

After his father’s death in 1926, Henry inherited Winterthur and started major renovations. In 1928, Marian began work on the landscape design. One major design change was the creation of a circular turnaround at the end of the driveway for the new entrance. Henry was very generous about opening his gardens for tours, and he was concerned about the traffic. He wrote to Marian questioning whether “the driveway in front of the house and also the turnabout near the tennis courts [were] big enough for those enormous buses.” Marian continued to work with Winterthur until she was 79 years old, and their last project together was a redesign of the tennis court and croquet lawn.

Marian also designed the properties of other du Pont estates, Mount Cuba and Gibraltar. Her work for the du Ponts led to other commissions with some the wealthiest clients of the day, designing the estates of Senator H. Alexander Smith and Marshall Field, and the Hutton, Vanderbilt, and Carnegie estates. Marian gained national attention as the primary designer of large private estates, and in 1918, she became the second woman to be made a full fellow of the American Society of Landscape Architects. She also received an honorary doctorate degree from Hobart and William Smith Colleges. For more than 30 years, she was the landscape architect for the University of Delaware, where she was instrumental in combining the men’s and women’s campuses. Marian and Beatrix Farrand were the only other female college campus designers at the time.

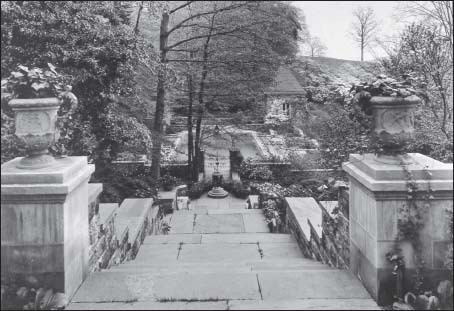

Winterthur, steps to pool.

Courtesy of the Winterthur Library: Winter Archives

When the Pavilion at Fort Ticonderoga in New York, “the oldest garden on this continent,” was to be restored, Marian was hired to work on the project; coincidentally, Marian was a direct descendant of a commander of the fort. In 1930, Marian was honored with the Gold Medal of the Architectural League of New York. While enjoying professional accolades, Marian decided to fulfill her childhood dream of becoming a great artist. Marian took up watercolor and oil painting, and she sold her paintings through a gallery on Fifth Avenue in New York City.

In 1927, when Marian was 51 years old, she and her mother inherited money and moved to New Haven, Connecticut, to be closer to relatives. In the springtime, Marian opened her Connecticut house and garden, and hosted a party to show off her paintings and plantings. Soon, her garden parties were a well-known and much-beloved social event in New Haven.

Marian wrote about her landscaping principles in Trees and Shrubs for Landscape Effects. She emphasized the design of the entire property, not just isolated gardens. The chapter titles illustrate this comprehensive approach: “Gardening with Trees, Approaching the House,” “The House and Its Setting,” “Lawn and Terrace Treatment,” “Backgrounds and Ground Covers,” “Walks Formal and Informal,” and “Woodland, Green and Other Gardens.”

In Marian’s 53-year career, she designed more than 130 landscape designs and wrote more than 70 articles. At the age of 71, Marian was asked to redesign the New York Botanical Rose Garden, which was originally designed by Beatrix Farrand in 1916. When Marian died on February 2, 1957, at age 81, she was still working on the Rose Garden. Her old and dear friend Warren H. Smith bought her house and continued hosting an annual spring garden party for 32 years in her honor.

Money, Manure, and Maintenance: Ingredients for Successful Gardens of Marian Coffin, Pioneer Landscape Architect, 1876-1957 by Nancy Fleming (Country Place Books, 1995)

The Spirit of the Garden by Martha Brooks Hutcheson (University of Massachusetts Press, 2001)

Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, 5105 Kennett Pike, Wilmington, Delaware, www.winterthur.org