Cornelia Hahn Oberlander.

Cornelia Hahn Oberlander Photo Library

One day, when Cornelia Hahn was 11 years old, she sat patiently while an artist painted her portrait. The only thing she had to look at was a maplike painting of the Rhine River on the wall. She noticed how the river curved and how the beige streets of the town met the river at right angles. The red blocks were the brick houses, and then there were green areas all over. Cornelia asked the artist, “What is the green?” The painter explained that those were the parks. Later that night, Cornelia told her mother, “When I grow up, I want to do parks.”

“You want to be a landscape architect?” her mother asked.

“That’s a difficult job,” her mother explained. “And, you will have to drive a bulldozer.”

“Good!” Cornelia replied, and went off to bed.

Growing up in Germany in the shadow of Adolf Hitler wouldn’t keep young Cornelia away from her dream of becoming a landscape architect. She was born on June 20, 1921, in Mülheim-Ruhr, Germany, a town north of the Rhine River. Cornelia’s mother was a horticulturalist, someone who studies the art and science of growing plants, and also wrote children’s books on gardening. She was one of the first people to introduce the Bantam seed, a seed used to grow a sweeter corn, from America to Germany. Cornelia’s father was an engineer and worked in the family steel industry, Hahnsche Werke. Her great-grandfather founded the first factory for manufacturing seamless pipes.

The branches of the Hahn family tree are filled with successful, altruistic ancestors. Cornelia’s grandfather, a professor of economics and history at the University of Berlin, along with her grandmother, were involved in public housing and community work, especially in and around Berlin. Her uncle Kurt was the founder and headmaster of Salem, a prestigious boarding school in Bavaria, and her uncle Otto won the Nobel Prize in chemistry and was often called the father of nuclear chemistry.

The steel factory where Cornelia’s father worked was in a dusty, industrial town, so Cornelia’s mother requested that they move. They chose the village of Düsseldorf, where they had a beautiful garden full of daisies. As a small child, Cornelia spent her playtime picking flowers in the garden. Around this time, Cornelia’s father moved briefly to America to study scientific management with Lillian Gilbreth. His first job was helping Lillian create her “Kitchen Practical” exhibit, which was unveiled at the Women’s Exposition of 1929. Cornelia’s father was very excited by what he learned there, but Cornelia’s mother didn’t like America and didn’t want to live there. When her husband returned to Germany, the family moved to Berlin and into a house that had an even bigger garden. Cornelia had her own four-by-four-foot garden bed in which she could grow whatever she wanted. She chose to grow peas and corn.

Cornelia was homeschooled until she was eight years old. Once she started in a regular school, she was one of the few Jewish students. Some Jewish families were emigrating to other countries, seeing the rising threat of Nazism. On New Year’s Eve when Cornelia was 11, her mother promised her father that they would leave Germany for America soon. Two weeks later, her father was killed in an avalanche while skiing. Cornelia was devastated, but her mother told her, “He could as easily have died crossing the street. You can’t stop living.”

Cornelia and her sister, Charlotte, continued with their normal activities of English and French lessons and swimming in nearby Lake Wannsee. Cornelia inherited a horse named King from some Jewish friends who had fled Germany. She taught herself how to ride and how to do circus tricks on the horse.

One Sunday afternoon when Cornelia was 14, the Nazi Gestapo pushed into the Hahn house. They were looking for evidence that they were breaking a new law that said that once per month everyone in the house must eat a one-pot soup. If they had been eating their normal roast beef dinner, they could have been arrested. The smell of the Nazis’ uniforms and the black marks left from their boots created a lingering and terrifying memory for Cornelia.

On Cornelia’s 16th birthday, she received a letter with a poem from her grandmother. The poem read:

With columns covered with clematis, summer houses surrounded by roses, and little rivers trickling over stones.

And you will have thought of all this out of thousands of remembrances….

Every thing you have contact with will be woven into your garden….

What you have created with the blood of your heart will be remembered by future generations.

Her grandmother’s words foreshadowed Cornelia’s life working and living with gardens, and formed a bittersweet good-bye to her granddaughter, who would soon be leaving Germany.

When the Queen Mary docked on the New York Harbor, 17-year-old Cornelia wanted to fit right in to the American scene, and she begged her mother to let her cut off her German braids. They settled first in the city of New Rochelle, New York, but Cornelia’s mother felt that it was too materialistic for her daughters. To get out of the city, her mother bought 200 acres in New Hampshire, part of the 6,000-acre farm of the 18th-century governor John Wentworth. Cornelia was so excited to be able to drive something similar to a bulldozer, an old Ford tractor. During the war, the Hahn family grew vegetables on the farm using new organic methods.

Cornelia could think of nothing else but her dream of becoming a landscape architect. A year after arriving in the United States, she discovered that Smith College in Massachusetts had an interdepartmental major in architecture and landscape architecture. Her mother suggested that Cornelia apply to some other schools farther afield, such as the University of California, Berkeley; the University of Michigan; and Vassar College. But Cornelia wanted to stay in New England, where she could study with Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer, famous architects and friends of her parents in Germany. At first she was denied admittance to Smith, allegedly because of her German accent, but when she showed them her high school grades, they let her enroll in the college.

Driving down the long road toward Smith lined with oak and London plane trees, Cornelia couldn’t wait to learn all about plant materials, construction, landscape history, architectural drawing, and research. Before that, books had been her only source of study.

During field trips to design sites, the students had to carry heavy surveying tools and other equipment, in all sorts of climates. Cornelia loved studying the challenges of each site, from poor drainage to high winds, and she didn’t care about the rough conditions.

Women who wanted to become landscape architects went to the Cambridge School, a part of Harvard University, because at that time women could not attend Harvard. But that changed during World War II, and in 1943, Cornelia was one of the very first women to be admitted to the Harvard Graduate School of Design. At Harvard, she studied basic design, surveying, contours, road construction, drainage, and architectural features such as steps, terraces, pools, and walls.

At Harvard, Cornelia lived with her aunt and uncle, who had also settled in America. She rode her bicycle to school, carrying her papers and drawing equipment in the front basket. Her social life centered around skiing on the weekends. On Fridays, she would leave for the Harvard ski cabin in Stowe, Vermont, at about four o’clock and return by noon on Mondays. Being in the outdoors in the forest and woods refreshed Cornelia. (Years later people have asked her where she gets her energy. Cornelia replied, “I am absolutely certain that these years of being out of doors and living on my mother’s farm are the places where I gathered all the energy.”)

When Cornelia was 24, while at a Harvard class picnic on Walden Pond, she met Peter Oberlander, a young Harvard student working on his master’s degree in city and regional planning. Peter just had to meet the girl who brought the gugelhupf—German raisin cake—and he was introduced to Cornelia. Months went by, and Peter finally called Cornelia and asked her to go see a movie with him. When he arrived for the date, Cornelia was surprised to see him carrying a T square, drawing board, and book bag. He explained, “I’m working on a management study for a new town. If you’ll help me for two hours, we can still make the late show.” They never made it to the movie. The couple worked on the project together for the next 48 hours, and Cornelia knew that this was the man she was destined to marry.

In 1951, Cornelia moved to Philadelphia to serve as community planner for the Citizens’ Council on City Planning and worked on the Millcreek Housing Project with the famous architect Louis Kahn. One day, after a meeting, Cornelia noticed children hanging around on the street with nothing to do. She thought, “It’s too bad that these kids don’t have the chance to enjoy nature the way I did.” She noticed the empty lot across the street; the ground was dried dirt with a few weeds. She thought, This could be a wonderful place for mothers and children. Cornelia went to city hall, found out who owned the empty lot, and convinced them to let her design a park for the neighborhood. That project led to her being asked to design an entire housing project, which led to many others. At 30 years old, Cornelia was finally doing what she had dreamed of since she was 11.

During this time, Peter had been working in London and Ottawa, Canada. When he was offered a teaching job at the School of Architecture at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Peter asked Cornelia to marry him. On January 2, 1953, they were married at city hall, and Cornelia welcomed the adventure of moving across the continent.

In Vancouver, Cornelia began a small landscape architecture firm. She became interested in the modern art movement, which combined art and architecture to address the connections between urbanism and surrounding natural settings. Between 1956 and 1960, the Oberlanders welcomed three children: Judith, Timothy, and Wendy. While watching her children play, Cornelia realized that all children should have woods and water to play in. She thought, “If kids don’t have contact with nature, how will they ever come to understand it, learn to care about it, respect it, and cooperate with it? If kids are to grow up and be caretakers rather than destroyers of the life on our beautiful blue Earth, there has to be a way to make contact with nature possible!”

“If kids don’t have contact with nature, how will they ever come to understand it, learn to care about it, respect it, and cooperate with it?”

Cornelia became a specialist in designing children’s playgrounds. She was asked to design the playground at the Children’s Creative Center at Expo ’67 in Montreal. She wanted kids to run, climb, crawl, build, dig, and get wet. She designed sand areas, shade trees, logs to build with, and an artists’ area. There was even a mound and a canal with a boat. Critics were skeptical at first, but Cornelia knew how children played. One Expo visitor was overheard saying, “A playground without swings and slides? Why, it’s simply—un-Canadian!”

But soon, similar playgrounds were built around North America, after the world saw how they allowed for creative play. Also, it didn’t hurt that Cornelia’s imaginative designs were less than half the cost of traditional playgrounds implemented with their swings, slides, and jungle gyms. All totaled, she designed more than 70 playgrounds. She also assisted in drafting national guidelines for children’s playgrounds.

A wooden boat in the canal in the Expo ’67 playground designed by Cornelia.

Cornelia Hahn Oberlander Photo Library

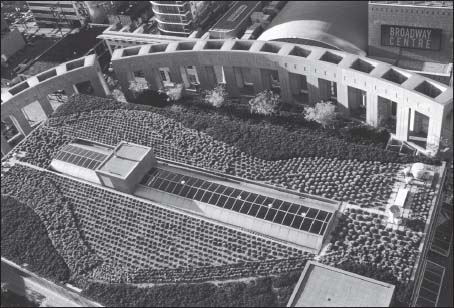

During her career, Cornelia designed the landscapes of many high-profile buildings in both Canada and the United States. Increasingly, she practiced sustainable development, which involves not taking more from the earth than you give back. The rooftop gardens she designed on the Vancouver Public Library became a model for green roof designs in North America. The public plaza Robson Square, which covers three city blocks, has been called “a magnificent oasis in the middle of Vancouver.” Cornelia fought for her plans at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa when the all-male board said she was crazy. Proving the worthiness of her ideas, a year after it was completed, her design won the National Award of Excellence by the Canadian Society of Landscape Architects. By concentrating on her “three Ps”: patience, persistence, and politeness, Cornelia dealt with bureaucracy, which seemed to stop her every five minutes. She used research and examples to push through her innovative ideas to the masses not ready for change.

“At its best, landscape architecture creates a dialogue between art and nature, taking inspiration from both.”

Cornelia believed that “at its best, landscape architecture creates a dialogue between art and nature, taking inspiration from both.” She remains inspired by a quote from The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky: “Love all that has been created by God, both the whole and every grain of sand. Love every leaf and every ray of light. Love the beasts and the birds, love the plants, love every separate fragment. If you love each fragment, you will understand the mystery of the whole resting in God.”

In her 60-year career, Cornelia has always practiced “the art of the possible” with patience, perseverance, and politeness, with added doses of professionalism and passion to help get her through. Cornelia continues to work and live in Vancouver, British Colombia. On October 1, 2012, she was presented with the American Society of Landscape Architects medal, that organization’s highest honor.

Sustainable, or “green,” landscaping means planning and designing outdoor spaces that are responsive to environmental concerns. These days, sustainability is a foremost concern in landscape design. Strategic site planning, tree canopy coverage, and green roofs, which are completely covered with vegetation, are some sustainable landscaping practices that create a reduction of storm water runoff, improve air and water quality, decrease the urban heat-island effect, and save energy.

The Vancouver Public Library green roof was one of 21 projects in North America nominated for a Green Roofs Award of Excellence.

Cornelia Hahn Oberlander Photo Library

Cornelia with a contractor at the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

Courtesy of Elisabeth Whitelaw

Cornelia Hahn Oberlander website, www.corneliaoberlander.ca

The Cultural Landscape Foundation Oral Histories, Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, http://tclf.org/oral-history/cornelia-hahn-oberlander

Love Every Leaf: The Life of Landscape Architect Cornelia Hahn Oberlander by Kathy Stinson (Tundra Books, 2008)