The Vampire Controversy

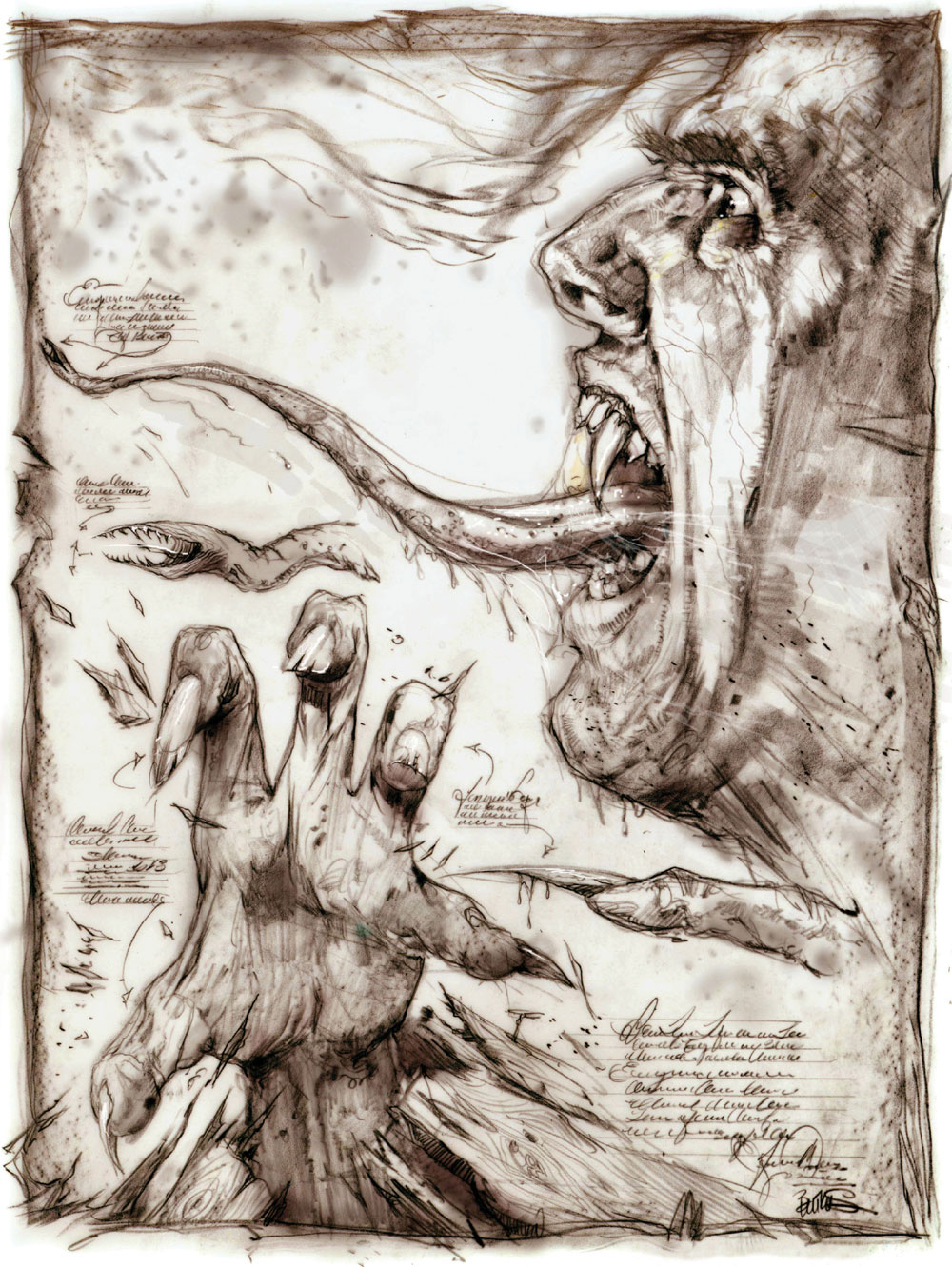

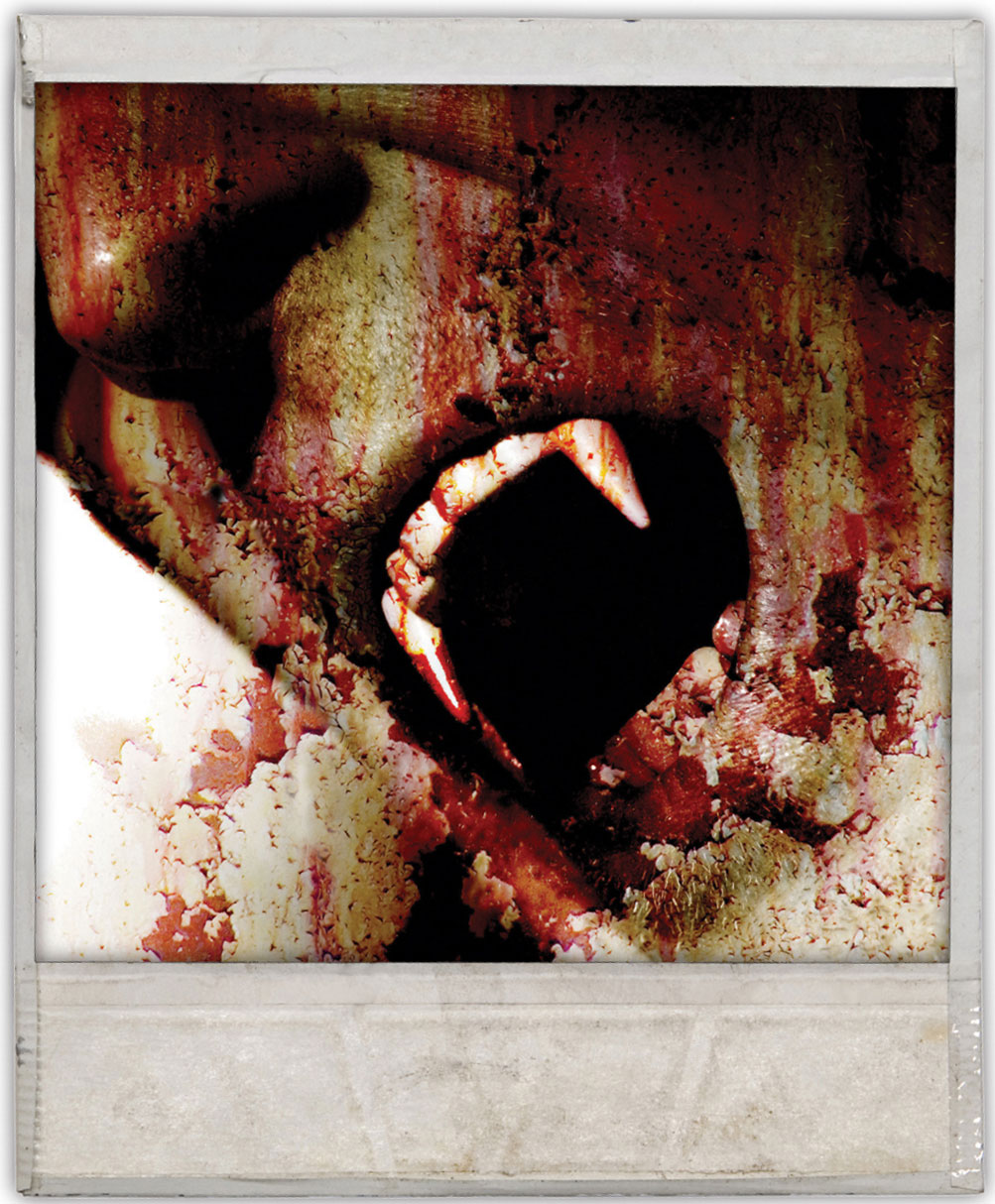

A full moon hovers on the horizon and a crowd of villagers stand around an open grave. A heartbeat passes, and then the coffin lid is pried off. Someone swings a lantern closer, casting beams of light upon the familiar figure that rests inside. An unholy gasp sweeps through the small gathering. The person inside the casket looks like a monster. Skin ruddy and bloated, blood seeping from nose and mouth, even the hair and fingernails have grown longer than when the body was interred.

On top of this, the loss of fluid—a common occurrence after death—has caused the gums to recede, and now the cadaver grins with long, ghoulish teeth.

In an age before embalming, these were all natural signs of decomposition.

But to the Eastern European villagers living in the 1700s, this was surely the mark of a vampire. To these people, this was one of the gruesome undead, a blood-sucking demon that needed to be destroyed.

Surprisingly, this is not the vampire we know today. Over the centuries, this creature has gone from a life-draining monster to a supernatural libertine to a high-school heartthrob. In contemporary literature protagonists now willingly invite vampires home for dinner—even though the tables could be turned at any moment and the hero/heroine devoured. TV shows like The Vampire Diaries, movies like Twilight, and books like Interview with the Vampire portray a modern, compassionate anti-hero who often struggles with guilt-ridden angst over dining on human blood, a pain reminiscent of the plight of the teenage vegan.

Where and when did this change take place?

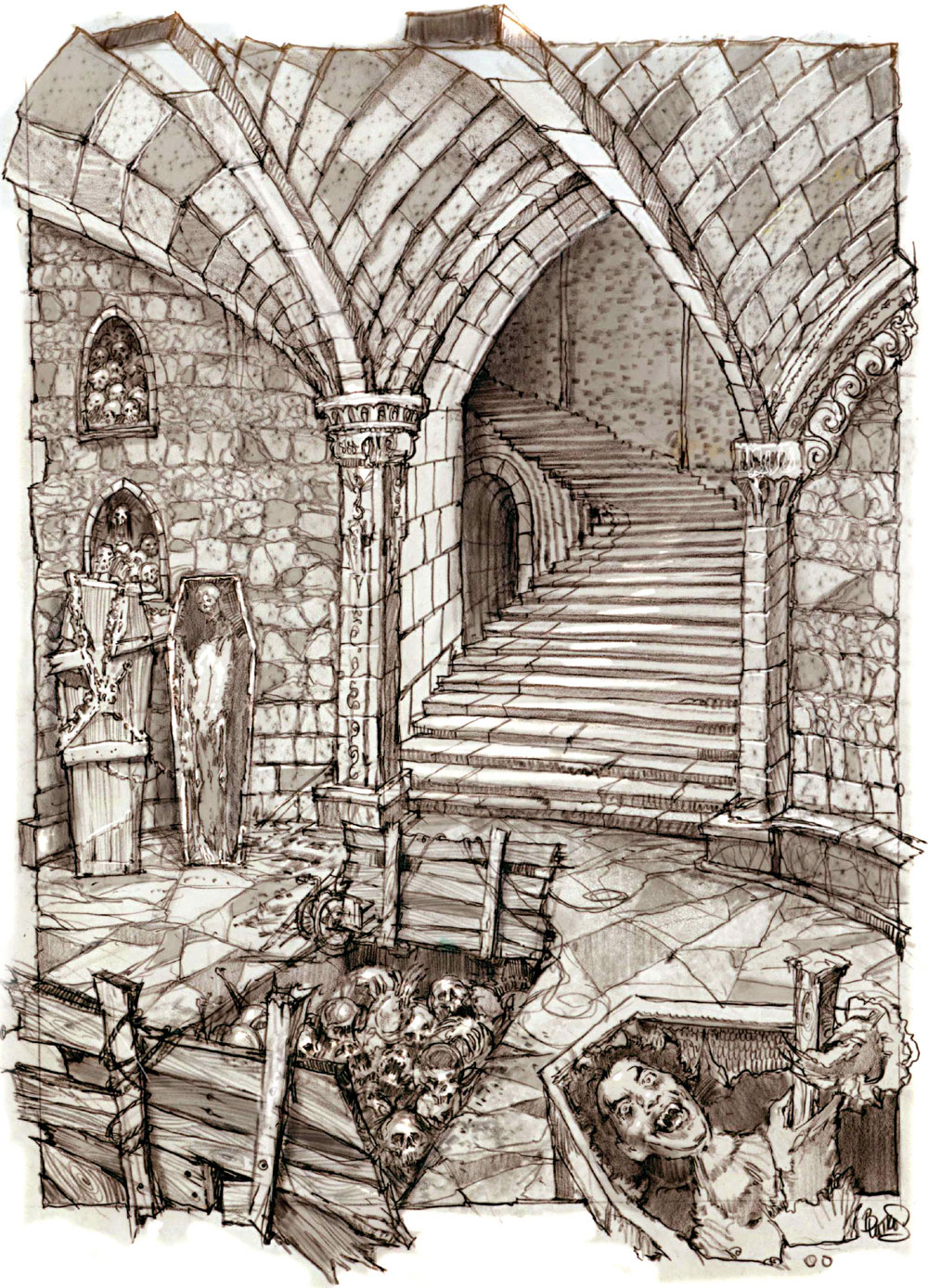

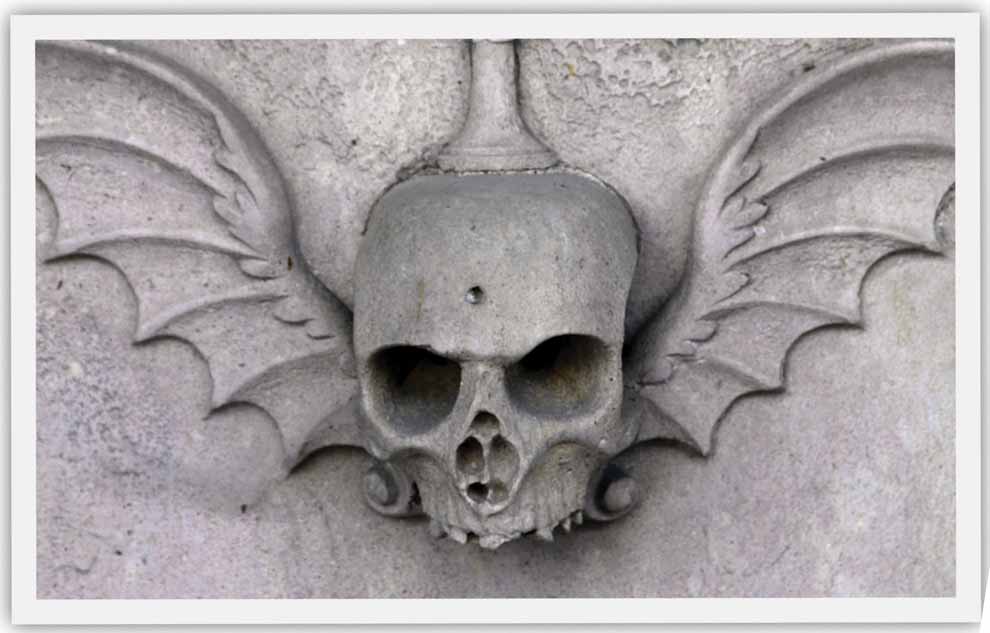

Until recently, vampires were loathed and feared around the world, sometimes to the point of mass hysteria. People exhumed the bodies of loved ones; they cut off heads and drove iron needles into hearts. They dismembered dead bodies, burned the remains, and then combined the ashes with water. This foul drink was then given to family members in an attempt to halt a vampire’s reign. Throughout the 18th century, Eastern Europe suffered from vampire mania, with frequent sightings that caused a near panic. Government officials wrote books and case reports on the subject and, as a result, superstition raged even stronger, causing villagers to dig up more bodies and then stake them.

The 18th-Century Vampire Controversy—as it was later called—got so out of control that the Empress Maria Theresa of Austria finally passed a law against the practice of digging up graves and desecrating the dead. This finally put an end to the madness.

Despite all this, however, the vampire legends continued. Many superstitions were remembered and practiced, whispered tales and so-called sightings kept this mythical beast alive—although the creature was always considered an undead monster. This was the beast of nightmares, not daydreams. Nearly another century would pass before the emergence of our modern vampire—a creature beautiful in shape and form and speech, who now possessed the ability to both charm and seduce. Aptly born in the midst of a worldwide tempest, this new monster would be modeled after a wildly romantic literary figure of epic proportions.

Legends and Myths

In order to fully understand the terrible reign of this undead creature, we must go back thousands of years to discover its true heritage. Known as the mother of all vampires, Lilu or Lilith was born from a twisting series of dark legends. Some claim she was once Adam’s first wife; others say she was a Mesopotamian demon. And an early rendition of her with bird talons and wings can be seen on the Burney Relief, circa 1950 BC. Later, in the 9th century BC, she resurfaced in the pantheon of Babylonian demonology. Here, she became known as an evil creature who stalked and killed both pregnant women and newborn babes. With a variety of names from Lamia to Kisikil-lilla-ke, her mythical misdeeds were recorded in Sumerian, Akkadian, and Hebrew. Modern authors C.S. Lewis and Neil Gaiman both drew inspiration from her ancient legends. Lewis’s White Witch in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe was supposed to be descendant of Lilith, while Gaiman included Lilith as Adam’s first wife in his comic book, The Sandman.

Moving on to ancient Egypt during the time period of 1400 BC, we hear another early tale of vampiric villainy that centered around the goddess Sekhmet. This warrior goddess, whose cult was so popular that it was moved from Upper Egypt to Lower Egypt, was also known as the ruler over menstruation. One myth states that she once almost destroyed all of humanity, and her bloodlust had to be slated through trickery. The sun god, Ra, convinced her to drink the Nile, which flowed swollen and blood red. The liquid was not blood, however, but a mixture of beer and pomegranate juice—and as a result, her fury was quenched in drunkenness.

Still more vampiric history can be found in Homer’s Odyssey, which many scholars date between the 9th and 8th century BC. In this epic Greek poem, Odysseus journeyed to the Underworld to seek counsel from the shade—or ghost—of the prophet Tiresias. The hero knew that if he wanted the shade to speak to him, he needed to give it blood from a sacrificial sheep to drink. Before long, however, Odysseus found himself surrounded by shades, all of them craving a drink of the blood that would allow them to speak.

The closest precursor to our modern-day vampire is found in the pre-Christian pagan culture of the Slavic people. With a spirit-based belief system, these people believed that the soul was eternal; they honored household spirits and practiced ancestral worship. They thought spirits could be either benevolent or malevolent and because of this, must be placated before they could do harm. To the Slavs, a soul could amble about after death for 40 days before journeying to the afterlife, during which time it either teased or blessed neighbors and family members. This wayward soul could also re-inhabit its own corpse, becoming a revenant: one of the walking undead who hungered for vengeance and human flesh and blood. Appropriate burial rites were believed to grant peace and absolution to unclean spirits—especially suicide victims, unbaptized infants, and accused witches—thus preventing their desire for revenge against the living.

As these beliefs merged with those of the Romanized sections of Eastern Europe, we saw the inclusion of the strigoi, or witches who could turn into vampires after death. Also added to this growing monster repertoire were the gypsy legends from ancient India. Sprinkled among tales of vampiric vetala, pishacha, Prét, and the dark goddess Kali, were rituals for warding off vampires. Here we meet the dhampir, a vampire hunter, himself born of a vampire. Some believed that vampires had the ability to become invisible, but a dhampir was able to see them. As a result of this legend, imposters roamed the Carpathian Mountains, pretending to be dhampirs, staging mock battles for villagers where they warred against these invisible foes. The dhampir may have been the inspiration for Van Helsing in Dracula, Blade in Spider-Man: The Animated Series, Anita Blake in Guilty Pleasures, and Buffy in Buffy, The Vampire Slayer.

Human Vampires

Still, not all of our current vampire legends have been built around mythological creatures. Many have been based on the evil deeds committed by humans. Throughout the centuries, many people have walked a labyrinth path of madness and psychopathic behavior, so demented that they have since been labeled vampires. Although these were real historic characters, the line between fact and fiction sometimes blurred over time—partly because the facts were almost too horrific to believe, partly because the legends about them grew with each retelling, and partly because many of the facts were impossible to prove.

The first of these sinister figures was Vlad III, the Prince of Walachia. Also known as Vlad the Impaler, his gruesome legacy inspired Bram Stoker and became the source for the title character in Stoker’s celebrated novel, Dracula. Born in 1431, his name—Dracula—means “son of the dragon.” In 1447, Vlad’s father and brother were murdered, and in 1459, he took revenge by arresting and then impaling those responsible, a powerful group of land-owning aristocracy known as boyars. With a reputation of killing more people than Ivan the Terrible, one story of Vlad Dracula claims that an invading Ottoman army turned back when they saw his handiwork: a forest of thousands of impaled corpses that lined the banks of the River Danube. While it’s unknown how many people died from Vlad Dracula’s sadistic torture methods, estimates range between 40,000 to 80,000.

The second vampiric human ancestor on our list was born in 1560. Countess Elizabeth Báthory lived most of her life in Hungary and later earned the nickname, “The Blood Countess.” Báthory and her four accomplices were accused and convicted of torturing and killing 80 young women—although one witness claimed the actual number went as high as 600. In 1610, Báthory’s sentence included a bizarre form of house arrest where she was bricked alive into a series of rooms within her own castle. She remained there until she died four years later. Since her death, legends have been told that the countess bathed in the blood of her victims, perhaps hoping it to be a fountain of youth. It is more likely, however, that she committed these crimes out of her own inhuman desires.

The final person who influenced our modern vampire legends was not a mass murderer. He was a dangerously charming nobleman, famous for writing volumes of poetry and infamous for his romantic liaisons with both women and men. Accused of an incestuous relationship with his half-sister and challenged to duels by his critics, his numerous love affairs included English noblewomen and, quite possibly, a 12-year-old Greek girl. If ever there were a model for the handsome and charismatic vampire with the ability to drain the life out of those he met, it was most certainly Lord Byron.

The Romantic Monster

It began in 1816—during The Year Without a Summer, when world climates plummeted drastically due to volcanic activity in Mount Tabor—as a group of writers and poets gathered in Lake Geneva for a holiday. Included in this literary huddle were Percy Shelley, Mary Godwin (later Mary Shelley), Lord Byron and his personal physician, John Polidori. Kept indoors by the continually dreary weather, they soon grew tired of reading ghost stories and decided to write gothic tales of their own. Birthed from this challenge were Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Byron’s “Fragment of a Novel,” which later influenced Polidori to pen the first English vampire story. Published in 1819, Polidori’s short story, The Vampyre, introduced readers to the aristocratic vampire, Lord Ruthven.

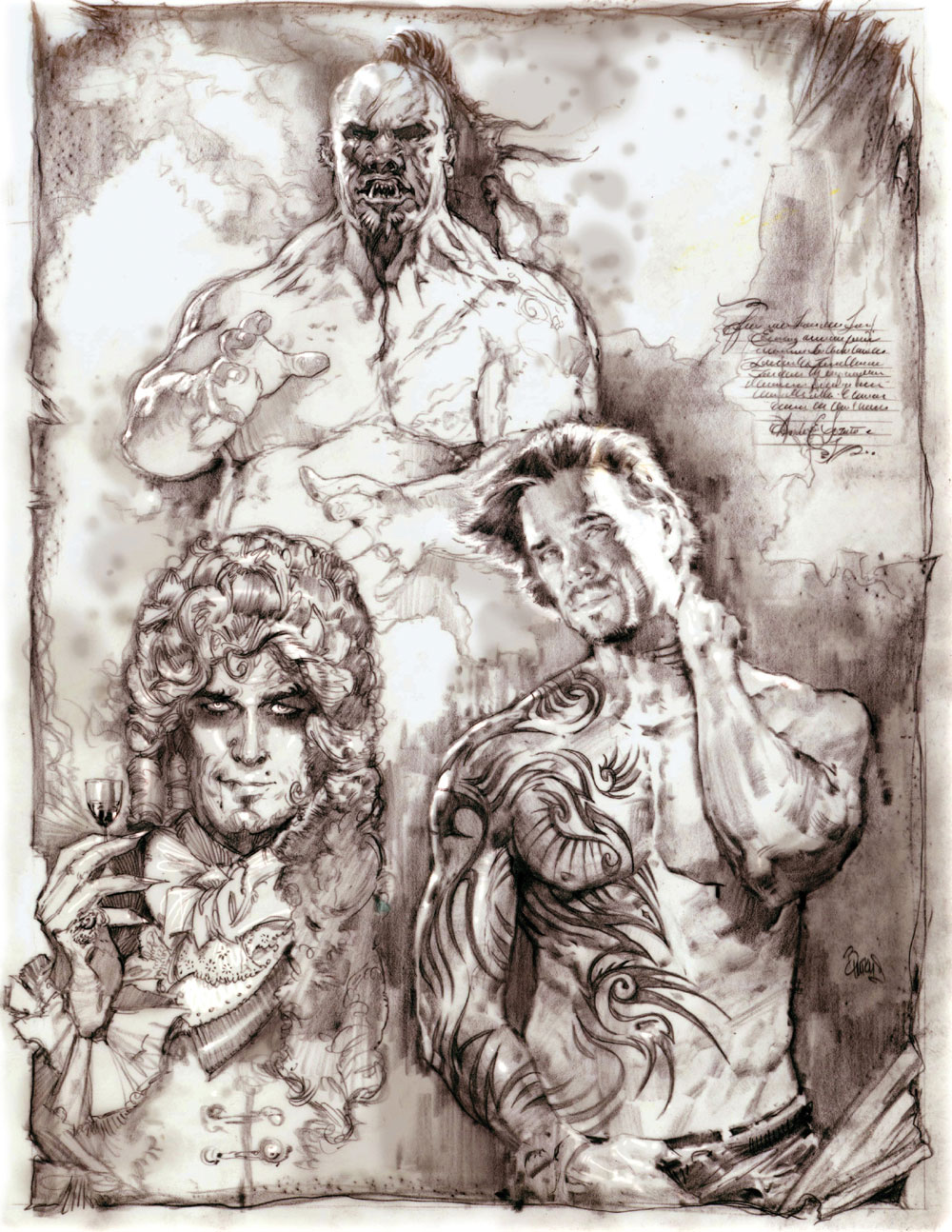

This new beast no longer bore a resemblance to the folkloric dark-skinned demon; it had now evolved into a pale-skinned, well-dressed nobleman, both erotic and mesmerizing. Lord Ruthven was fashioned in Lord Byron’s image, complete with romantic adventures that echoed the poet’s escapades and soul-draining activities. Polidori had used the ancient vampire legends as a metaphor for Byron’s depraved, self-indulgent lifestyle.

This new, dark interpretation of the old legends resonated with readers and writers alike and spawned a new genre. The Vampyre went on to influence Bram Stoker’s Dracula and numerous other tales written by authors like Alexander Dumas, Edgar Allan Poe, and Alexis Tolstoy. In recent years, the vampire has gone from romantic literary protagonist to cinematic anti-hero. Now the misunderstood bad-boy-with-a-curse is more popular than ever in characters like Edward Cullen in Twilight, Stefan Salvatore in The Vampire Diaries, and Bill Compton in Dead Until Dark.

It’s possible that the vampire frenzy of the 18th century never truly died.

It may have simply been waiting in the crypt for that day when the coffin lid would swing open and it would be resurrected by the fresh blood of fans around the world.

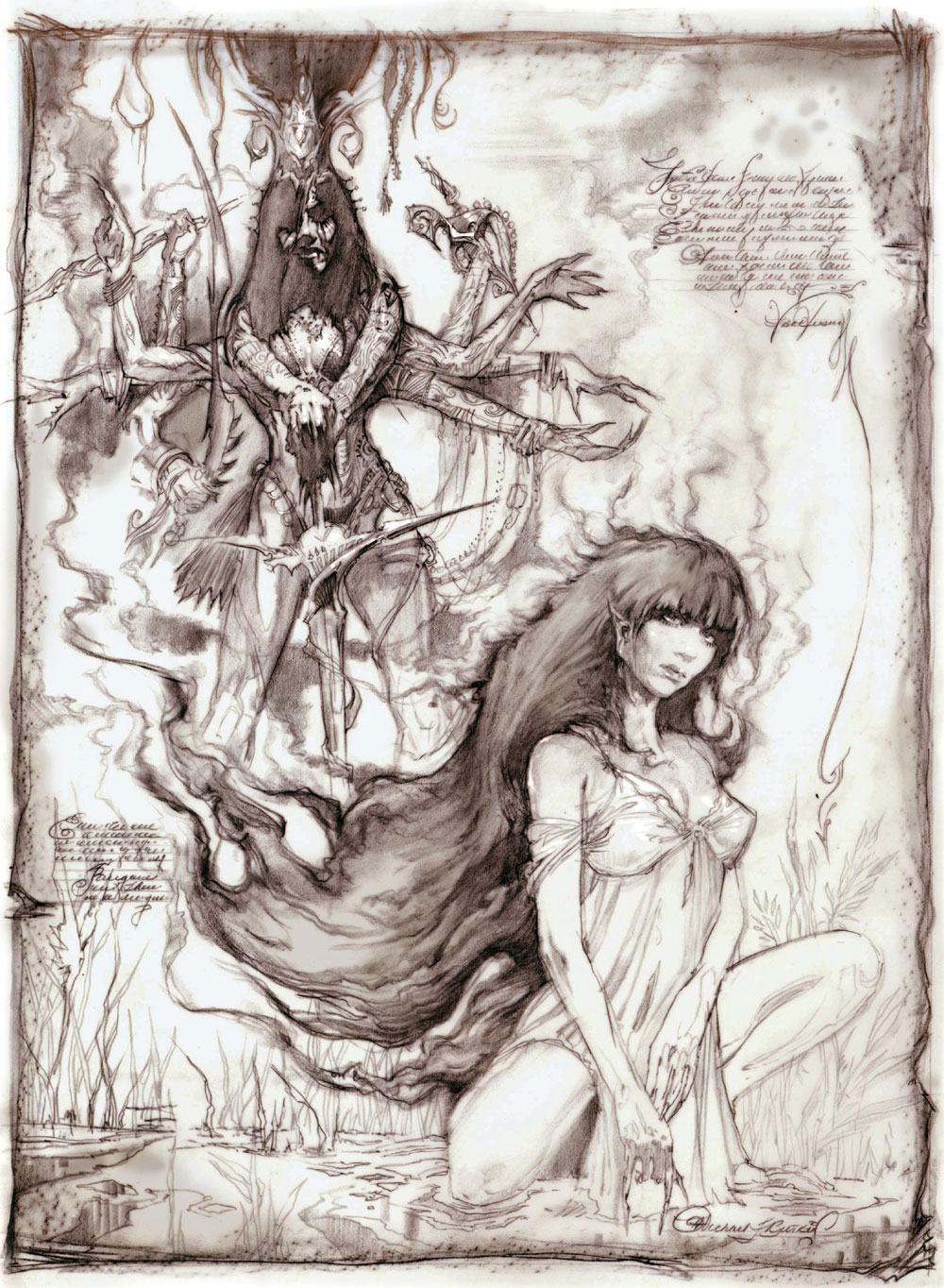

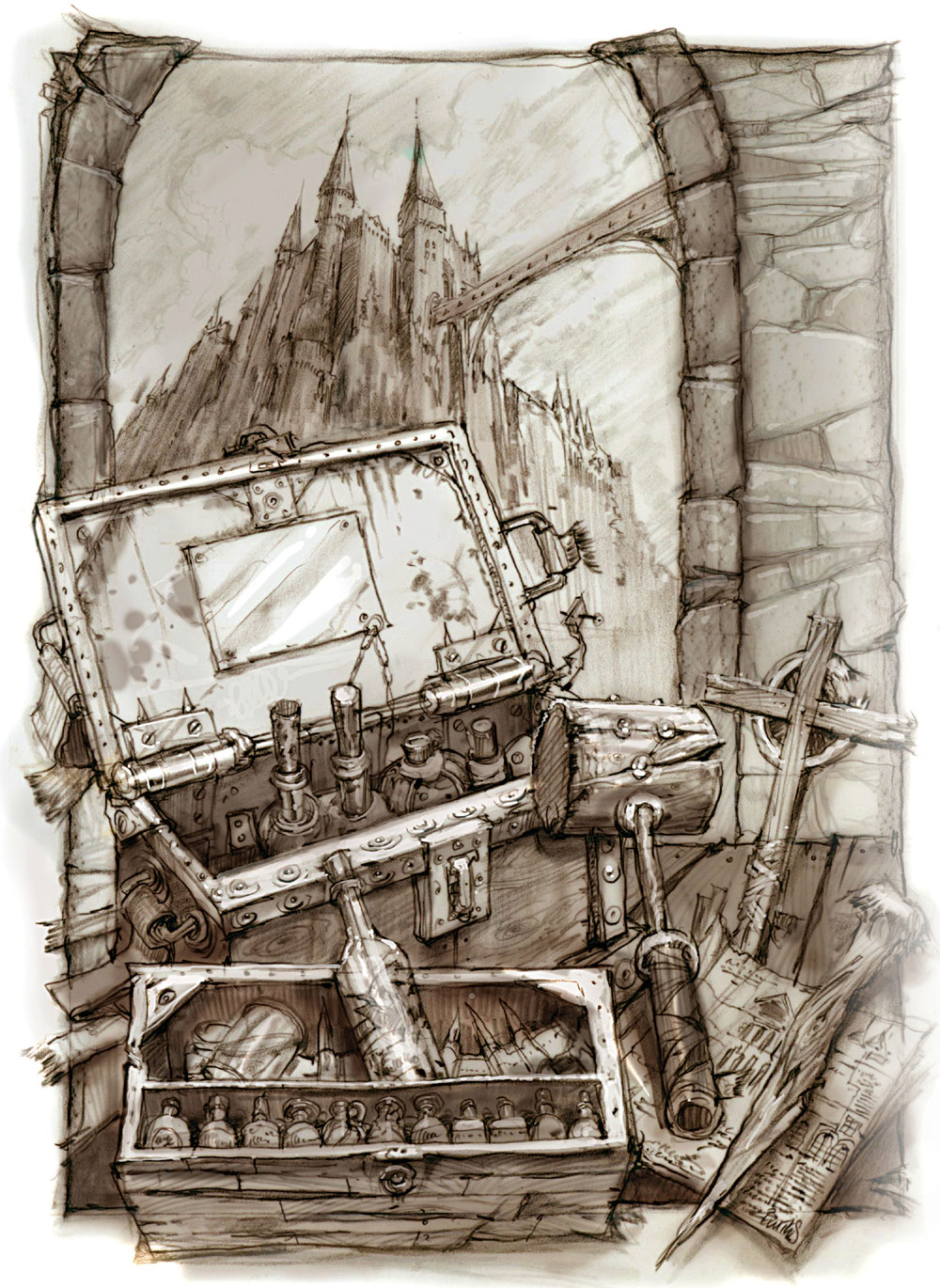

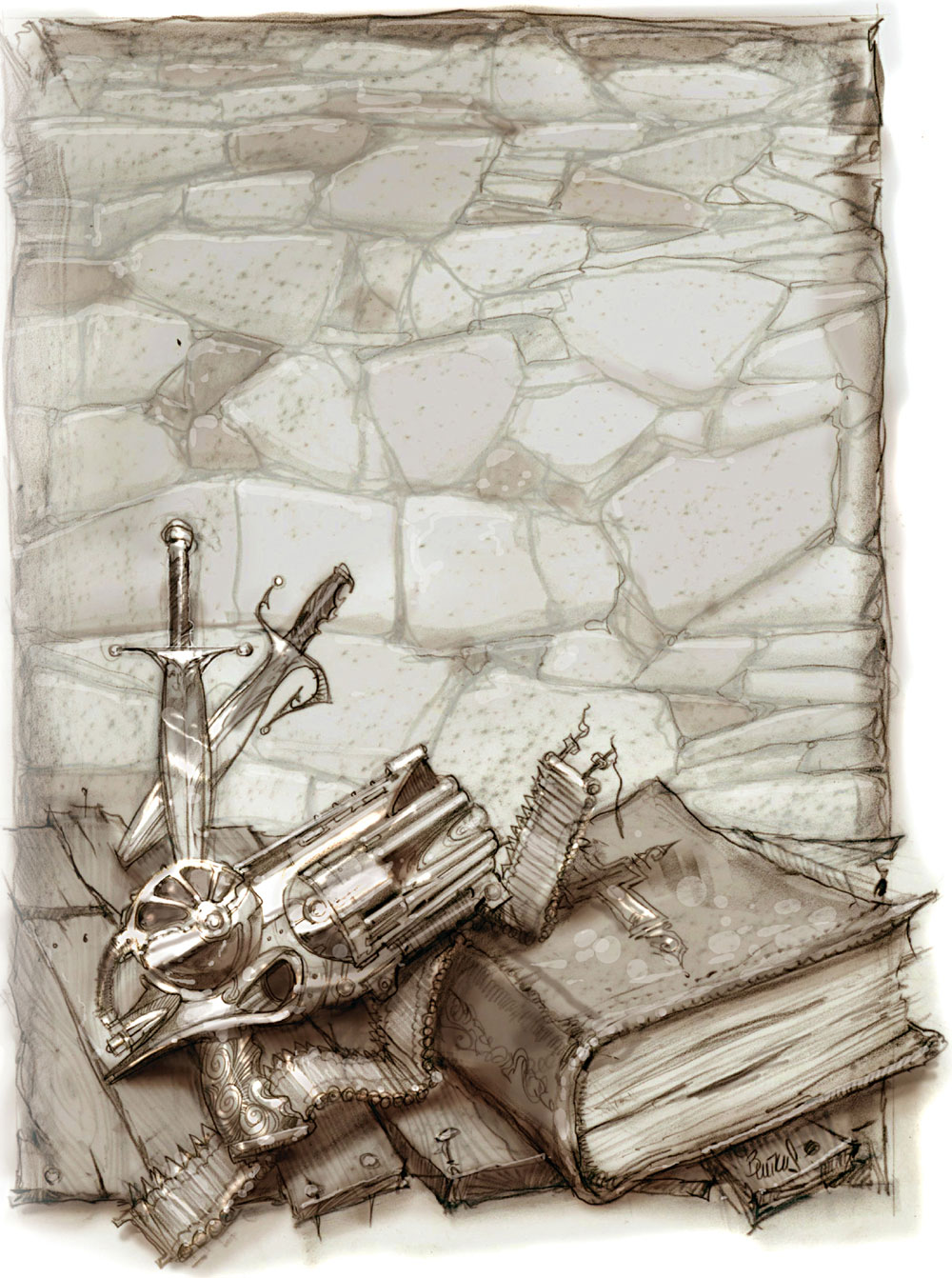

In Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, vampire hunter Abraham Van Helsing pursued the legendary Count Dracula. Here, we have pages from Van Helsing’s illustrated journal, featuring notes he took when he later traveled around the world, hunting and killing these immortal beasts. He even aptly predicted the twists and turns the vampire evolution would take over the succeeding centuries.

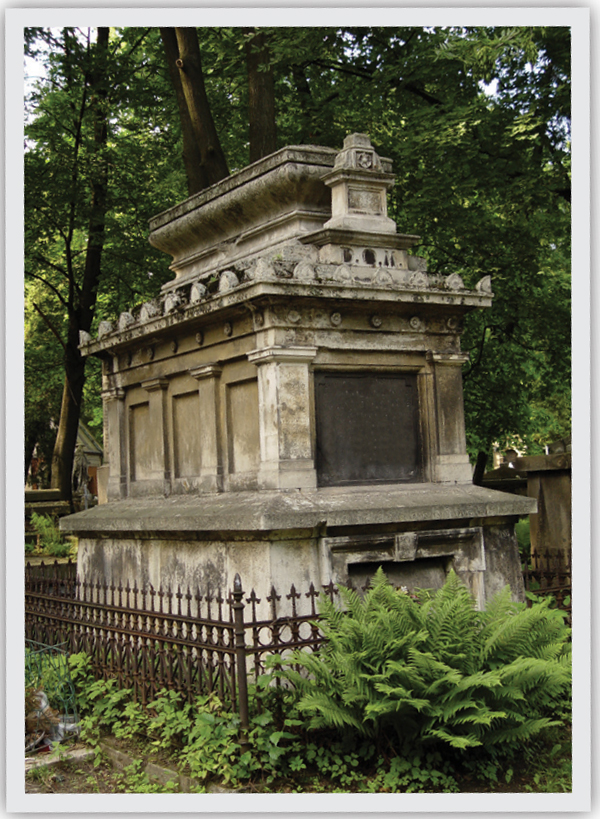

Nothing says “vampire” like a moody, gothic setting cobblestone streets, cottages with thatched roofs, and flickering gas lamps on street corners : all of these elements help to set the stage for your illustration and will make your immortal monster seem even more real.

From time immemorial, vampire hunters have stalked the undead. Often led by dhampirs, or half-human/half-vampire trackers, these assassins need the right accoutrements if they hope to succeed. Depending on where the battle will take place, weapons range from holy water and crucifixes to wooden stakes and silver bullets. In some parts of the world, even a vial of poppy seeds or a bag of rice might come in handy—for the vampire would be required to count every grain before continuing his bloody rampage. Since this endeavor could take hours, there’s always hope that the sun might rise and finish the task before any more victims lose their lives.

Vampires have changed over the centuries, as legends of these undead creatures spread from one country to the next. From the gypsy folklore that began in the heart of India to the contemporary vampire romance novel, each story leaves its mark on this immortal beast. Once he couldn’t survive in sunlight, now it makes him glisten. Once he reveled in his hunt for blood, now he regrets it.