AUTHOR’S NOTE

THERE ARE MOMENTS in history that grab me tight and don’t let go. When I came across Matt Herron’s photos of the Selma-Montgomery march at

www.takestockphotos.com, shivers chased up and down my spine. I headed for the library. After reading through a stack of books, I was totally and completely hooked. The march is loaded with so many rich themes: the brilliant strategies Dr. King employed, his devotion to civil rights, the backstage alliance between Dr. King and President Johnson. I wanted to know more about what led up to the combustion in Selma: the incredibly complex history of slavery, Jim Crow, and crippling legislation.

I found the story of the march has often been told from the viewpoint of important civil rights activists like Dr. King, Andrew Young, and John Lewis. But as Lewis acknowledged, Selma was not like the other movements, with leaders planning every move. “Selma was more of a bottom-up campaign,” said Lewis. “We were there to guide and help carry out what the people wanted to do, but it was essentially the people themselves who pointed the way.”

What people?

Women like Amelia Boynton and Mrs. Johnson. But the adults couldn’t do it alone. It took hundreds of kids and young adults who walked right into jail, into billy clubs and cattle prods, over and over again. Their individual acts of determination and bravery, added together, left an indelible mark on America.

I’d found the story I wanted to tell: how these kids changed history. I was awed by their commitment to nonviolence, to meeting brutality and hatred with love. I wanted to understand how simple, easy-to-remember songs helped them to be so courageous. I wondered ... would I have been that brave?

I went to Selma, Alabama, to interview people who’d been kids and young adults during the movement. They’d grown up, married, had children, worked, gone to school, moved away, returned to Selma. I asked them to take me back to 1965. I wanted to hear about their families, school, being in jail, their favorite songs. They all spoke of Bloody Sunday as the most terrifying day of their lives, and walking into Montgomery as one of the most ecstatic. In recent years they’d become aware of the devastating price they’d paid for being out there, vulnerable, day after day. “There’s a lot of pain in all of us that never came out,” said Charles Mauldin when I interviewed him. Joanne Blackmon Bland agreed. “You don’t realize how damaged you are.”

But they didn’t waste any time feeling sorry for them-selves. What stirred them all were the changes that had come and continue to come. “It’s the good times that make you cry,” Charles told me. “Not the bad times. You’ve seen something be accomplished and it really is heart-rending.” They also considered their involvement in Selma as part of a bigger picture. In an interview with the National Park Service, Joanne Blackmon Bland said, “They like to say these particular struggles were black struggles, but they were not.... We fought this movement primarily because it benefited us as a whole. But if you look at the pictures and read about the history of it, it was not a black movement—it was a people movement. And the future has to be a people movement, until injustice is stamped out in any form.”

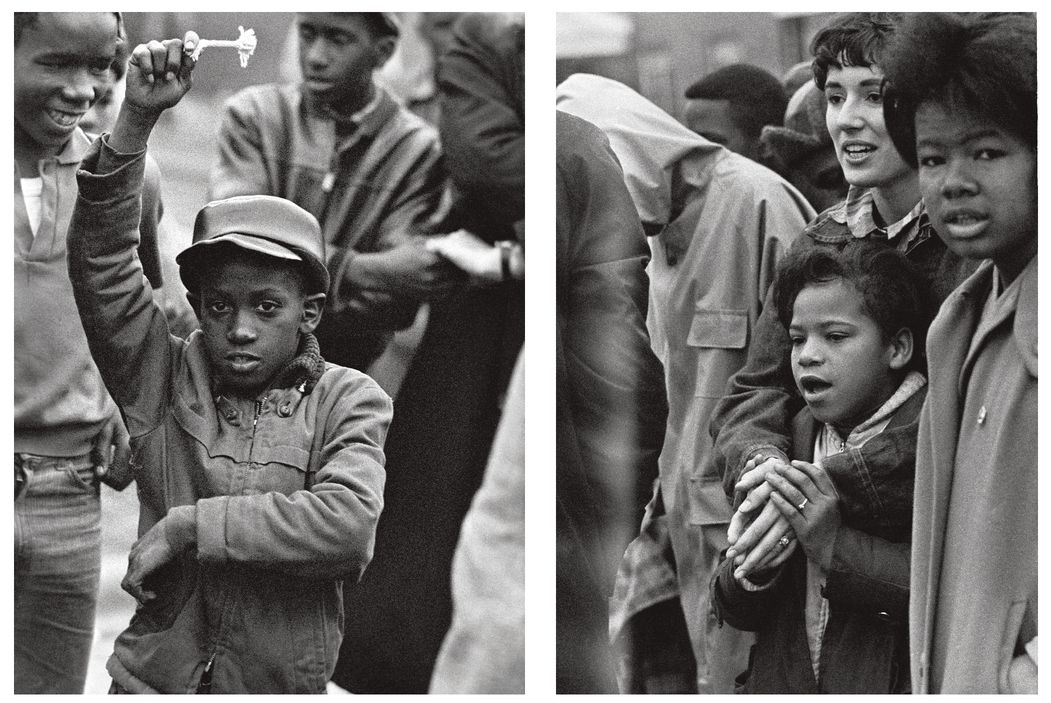

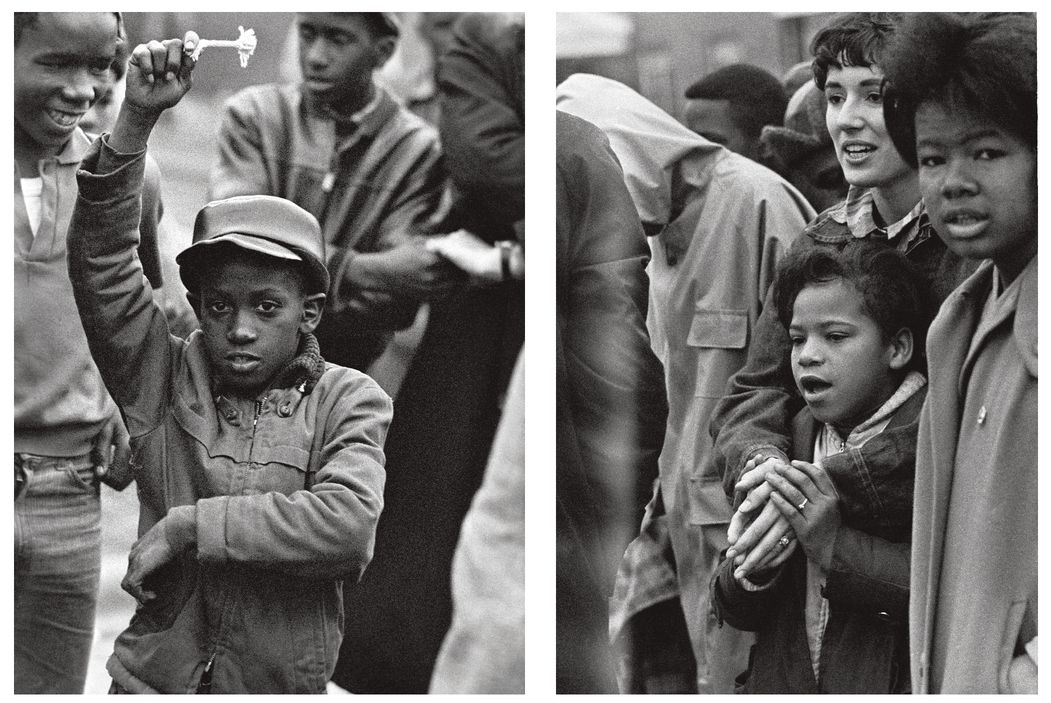

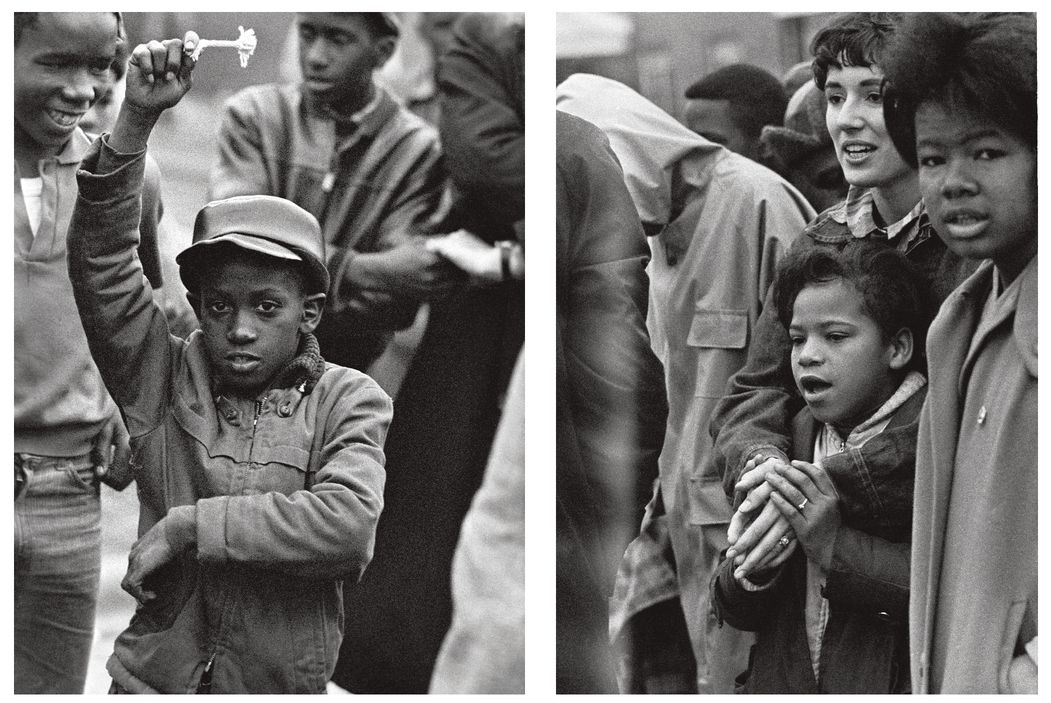

The “Berlin Wall, ” first a wooden barricade, was replaced by a thin rope. The barrier was removed after James Reeb’s death.

LEFT: A boy victoriously holds up a small section of the rope. RIGHT: Singing behind the Berlin Wall.

And we do it with the great democratic tradition: voting. So simple. So powerful.