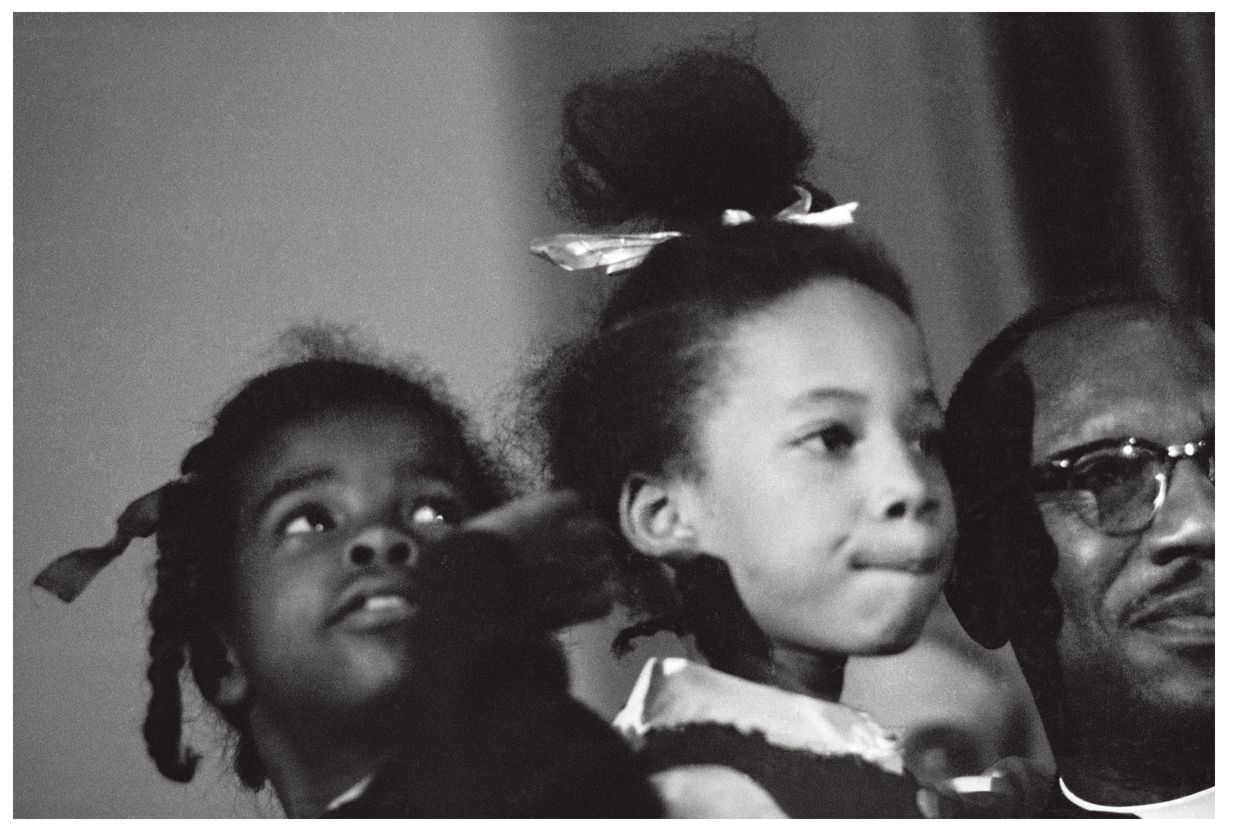

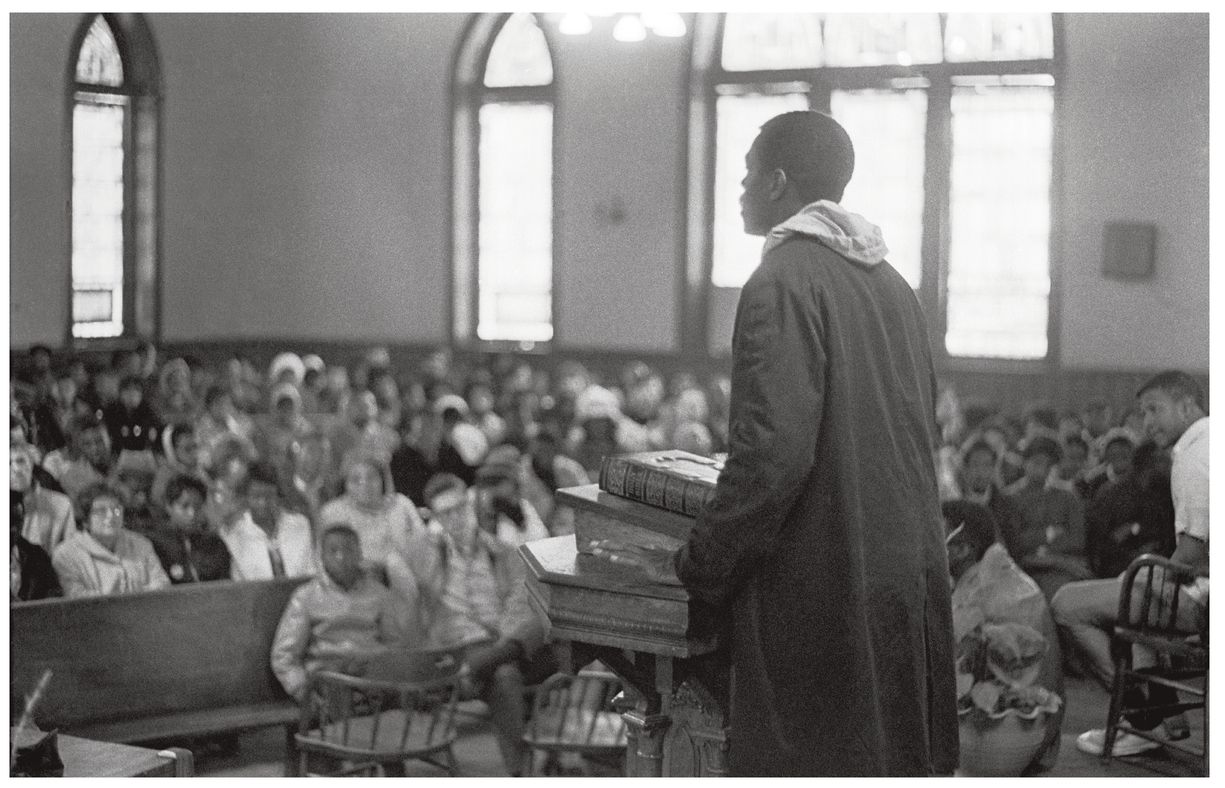

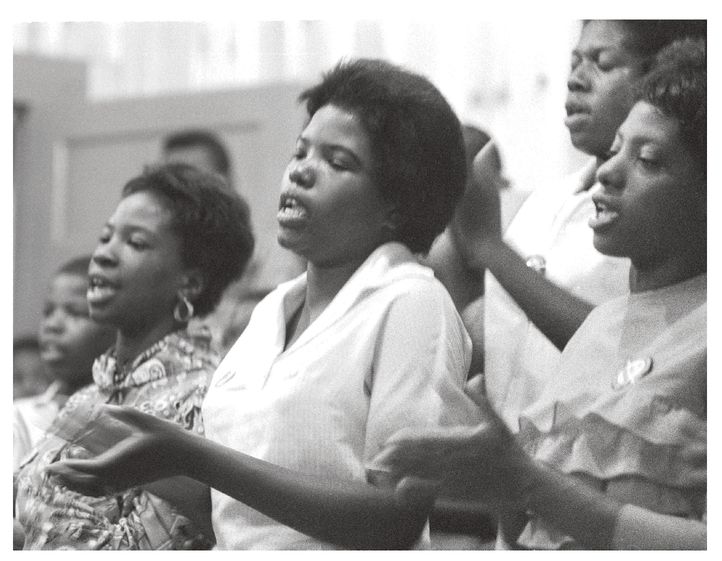

Gathering at Brown Chapel, March 1965.

MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. ARRIVES, 1965

January 2

IT RARELY SNOWED in Selma, but residents of the Carver Homes woke to a light dusting of snow sparkling on the unpaved streets. By early afternoon, people were heading for Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church, an elegant brick building set squarely in the middle of the Carver Homes.

Singing and clapping soon filled the church and poured out the windows and doors. The crowd swelled, and the singing gathered momentum. Before long, seven hundred people were crammed into the chapel, overflowing the pews and balconies, waiting enthusiastically for Dr. King and the hope he was bringing.

Dr. King addresses the packed pews at Brown Chapel, January 2, 1965.

This little light of mine

I’m going to let it shine

Let it shine, let it shine, let it shine

Like dozens of other children, Joanne and Lynda Blackmon were squeezed into a pew with their family. Now that Lynda was fourteen and old enough to help her father with the three younger kids, their grandmother had moved back home.

Standing silently in the back were two white deputies, noting who had come to the meeting, trying to make them feel vulnerable and exposed.

Dr. King arrived hours late but was greeted with a roar of welcome as he strode up to the altar. His voice washed over the crowd.

Selma, said Dr. King, was a “symbol of bitter-end resistance to the civil rights movement in the Deep South.... At the rate they are letting us register now, it will take a hundred and three years to register all of the fifteen thousand Negroes in Dallas County who are qualified to vote. But we don’t have that long to wait!”

“Yes, Lord,” people shouted.

“We must be ready to march; we must be willing to go to jail by the thousands,” Dr. King said. His voice rang out. “Our cry to the state of Alabama is a simple one: give us the ballot!”

“Amen,” came the eager response.

“We’re not on our knees begging for the ballot,” he said. “We are demanding the ballot.” The crowd jumped to their feet in a standing ovation.

Dr. King would need hundreds of people willing to turn out and protest, in rain and freezing weather. They might be shoved around by armed deputies, jolted with electric cattle prods, chased by men on horseback. They’d need to fill the jails, get bailed out, and go back again. No one—not even Dr. King—could predict what violence and suffering the segregation-loving authorities would unleash to keep blacks from voting. But not one person—no adult, no child—could fight back. Dr. King and his aides promised to teach protesters the principles of nonviolence, the ones Jesus and Gandhi had lived by. These principles had to be adhered to by every person, under any kind of duress, or the movement would fail. A single violent act by a protestor could be used to justify law officers’ full use of force, and public sympathy for the protestors would vanish overnight.

Listening to Dr. King preach in the warm, crowded church, Lynda knew right away that she wanted the free dom and dignity he was talking about. It would require, Dr. King said, a steady, loving confrontation. Lynda was willing to do whatever it took. She felt like he was lighting a fire deep in her soul.

Dr. King ended his speech that night promising he’d be back again and again, until they’d made it past every obstacle and the right to vote was theirs.

January 4-14

A FEW DAYS AFTER hearing Dr. King speak, eight-year-old Sheyann Webb headed out of her Carver Homes apartment for school. She hadn’t understood everything Dr. King was talking about, but she had felt his urgency, the importance of his message, the full-throated, joyful response he was given by the congregation.

Instead of crossing the street toward school, she lingered on the corner watching black and white people standing together, talking. She could tell something was in the air. When the people went inside the church, she slipped in behind them.

King had gone back to Atlanta for a few weeks, but there were forty or fifty people inside listening to one of his aides, Hosea Williams, a firebrand who always pushed for action.

Sheyann sat quietly in a pew listening to Williams explain the importance of the right to vote. The vote would mean freedom—freedom to vote for just laws, freedom to elect judges and mayors and governors who would make sure the laws were enforced. One of Williams’s phrases rang in Sheyann’s mind: “If you can’t vote,” he said, “you’re a slave.” Sheyann was mesmerized. When they broke for lunch she suddenly realized the morning was gone, and ran to school.

Excitement gathered around the SCLC and SNCC workers. Even what they called themselves—Freedom Fighters—felt promising. Some days Sheyann cut school and sat in the back of the church listening. When she went to school, her teachers would ask her what was going on in the church. What were the Freedom Fighters saying? Teachers were afraid to go to the meetings. The all-white school board would fire them if they went.

After school let out for the day, Sheyann would meet up with her best friend, Rachel West, who lived next door. Rachel’s parents had opened their apartment to take in King’s aides from out of town. James Bevel, an impassioned, visionary aide to King, was staying with them. He said gaining the right to vote was more important than anything they’d done before: it could open all the doors that were still shut tight.

The Freedom Fighters made a point of reaching out to teenagers, wanting to get them involved. To make the movement in Selma succeed, they’d need the full-on participation of people too young to vote. In the Birmingham civil rights protests in 1963, when there had no longer been enough adults willing to fill the jails, kids and young adults had stepped up. Being blasted by high-powered fire hoses hadn’t stopped them, nor had being attacked by snarling police dogs. As young as six, they’d stood their ground until arrested, then gone to

Rachel West and Sheyann Webb listen to speakers in Brown Chapel.

jail proudly, to the dismay of their terrified parents.

“Don’t worry about your children,” Dr. King had reassured parents. “Don’t hold them back if they want to go to jail.” He was in awe of their willingness and bravery. “They are doing a job for not only themselves but for all of America and for all mankind. They are carving a tunnel of hope through the great mountain of despair.” Kids were so integral to the success of the Birmingham struggle that it had quickly become known as the “Children’s Crusade.”

Now it was time for the students in Selma to step up. First, they had to learn to question the way they lived. “Why do you have to drink out of the ‘colored’ fountain?” the Freedom Fighters asked them. “Why can’t your mother and father vote?”

Charles Mauldin, a quiet, serious student at the all-black Hudson High in Selma, was intrigued. “I always had an answer for everything and I was really stunned because I had no answer for those questions.” There were so many aspects of segregation he had blindly followed. Why did he have to step off the sidewalk when a white person walked by? Why wasn’t he allowed to look whites directly in the face?

Charles remembered when he was eleven or twelve, hiding under someone’s front porch on Jefferson Davis Avenue, watching a long line of cars full of hooded Ku Klux Klan members drive openly, arrogantly, through his all-black neighborhood. It had seemed to Charles that more than a hundred cars rolled by. He realized he could be taken away by men in hoods, and nobody could stop them. What made it especially sickening was that he probably knew many of them from his job as a caddy at Selma’s all-white country club.

At first Charles was intimidated by what it would take to challenge the way things were in Selma. But he started going to meetings, listening to the Freedom Fighters. Nonviolence did not mean being passive. Students had to be willing to march in the streets and face off against the deputies so their parents could stand in line to register. Since they weren’t the breadwinners, teens and children could afford to go to jail repeatedly without jeopardizing the family’s income. The movement needed people to take dramatic risks to challenge unjust laws. Were the students willing?

Charles and other students were eager to accept the challenge, but one thing was nearly impossible to understand : How could they let someone spit on them, beat them, or hurt them, and not fight back?

Freedom Fighters explained they were already taking all kinds of hurt, being injured every single day. Violence was more than physical blows to the body: it was psychological blows to the mind and spirit as well. And did they react violently? No, they stepped off the sidewalk, kept their heads down. They did only what whites allowed them to do. Now it was time to stand up for their rights, for a sense of purpose and dignity, and to do it without any violence. They weren’t trying to dominate, or be the winner—they were trying to change their relationship with whites so they could be equal partners as Americans.

Charles spread the word. He encouraged others at his high school to come to meetings of the Dallas County Youth League in the basement of Tabernacle Baptist Church. With his steady, thoughtful ways, Charles was elected the group’s leader.

Bobby Simmons, another student at Hudson High, was skeptical that they could change their relationship with whites. “From a child up at that time you was taught to fear them,” he said. “Our parents explained to us kids that the white was almost the Great God or the Great Father. If they say we couldn’t go places, we couldn’t go.“ The Silver Moon Café, the Garden Café, Thirsty Boy Drive-In-all were off limits. Even after the Civil Rights Act outlawed segregation, the owner of Carter’s drugstore had hit a boy in the head with an ax handle when he’d sat down at the lunch counter. Bobby understood why parents insisted on obeying the rules. ”They had a lot of fear in them,“ he said, ”because of the punishment they had took and the abuse.“

Young convicts at work in the field in 1903. Boys and men were often shackled in heavy chains as they worked.

Bobby’s mother was hysterical. She thought they would all end up getting killed. She was terrified Bobby would be jailed. “Please,” she begged him, “leave that mess alone.” She was old enough to remember when conditions for jailed blacks were horrific. Up until World War II twenty-five years earlier, men—even teenagers and younger—could be snatched off the streets, thrown in jail on the flimsiest of charges such as vagrancy, using obscene language, or gambling. After being sentenced, they’d quickly be sold by the deputies in a convict leasing program—sold as laborers to plantations, lumber mills, turpentine camps, mines, and factories throughout the Deep South until they had worked off their jail time. Shackled, fed poorly, worked hard, and cruelly punished, many convicts died.

Bobby didn’t want to upset his mother. But something new was happening now, exhilarating and empowering. He would slip away from the house, not telling her where he was going.

The students began their meetings singing spirituals, gospel, and freedom songs—new lyrics put to comforting songs everyone already knew. Someone would “raise” a song—starting it up with a verse, and the others would join in. Their voices blended into a rich sound as they poured their commitment into the song.

Lynda made it to nearly every youth league meeting. She could feel that something really big was going to happen. “The movement was like a fire inside that just kept spreading and spreading and spreading,” she said. “It was not a fire that you wanted to put out. It was something that you wanted to increase and let burn.” Every morning she woke up singing freedom songs.

Joanne was the youngest to regularly attend the student meetings, and became the group go-fer. She didn’t mind. The talks at the meetings sometimes bored her so much she was happy to run errands. But where words failed, the singing reached deep inside her, filling her with the spirit of the movement.

Blacks and whites were not allowed to use the same restrooms. Segregation laws even extended to vending machines.

A teenager leads a meeting at First Baptist Church, where the students often gathered.

January 18-22

MONDAY, JANUARY 18, Dr. King returned to Selma and led an inspiring rally at Brown Chapel. The next day the courthouse would be open for voter registration, and he would march there with willing people. After his speech, Sheyann and Rachel were invited up to sing in front of the congregation.

Rachel got home to find her apartment jammed with people. Besides her seven brothers and sisters, Freedom Fighters filled the apartment, sitting on the couch, the chairs, even the floor. Rachel was excited and a little frightened. While her mother made cup after cup of instant coffee, they talked about the days to come. Rachel lay on the living room floor and listened. Right in her apartment were whites and blacks, Catholics and Baptists, all willing to put their lives on the line for one thing: freedom. That night, she fell asleep thinking this wasn’t just King’s movement or the people’s movement. It was something greater, something divine.

The next day was sunny but cold. Three hundred children and adults gathered in Brown Chapel and headed out. Sheyann walked with the one teacher in her school who dared to march, Mrs. Margaret Moore. They passed city hall on Alabama Street and headed to the courthouse.

While everyone waited outside, Mrs. Boynton took an old black farmer into the courthouse to register. He nervously began to fill out the form. The registrar, looking at his writing, said, “Now, you’re going across the line, old man. You failed already, you can’t register, you can’t vote, you just as well get out of line.”

The old man straightened up and looked right at the registrar. “Mr. White Man,” he said, “you can’t tell me that I can’t register. I’ll try anyway. For I own a hundred and forty acres of land. I’ve got ten children who are grown and many of them are in a field where they can help other people. I took these hands that I have and made crops to put them through school. If I am not worthy of being a registered voter, then God have mercy on this city.“

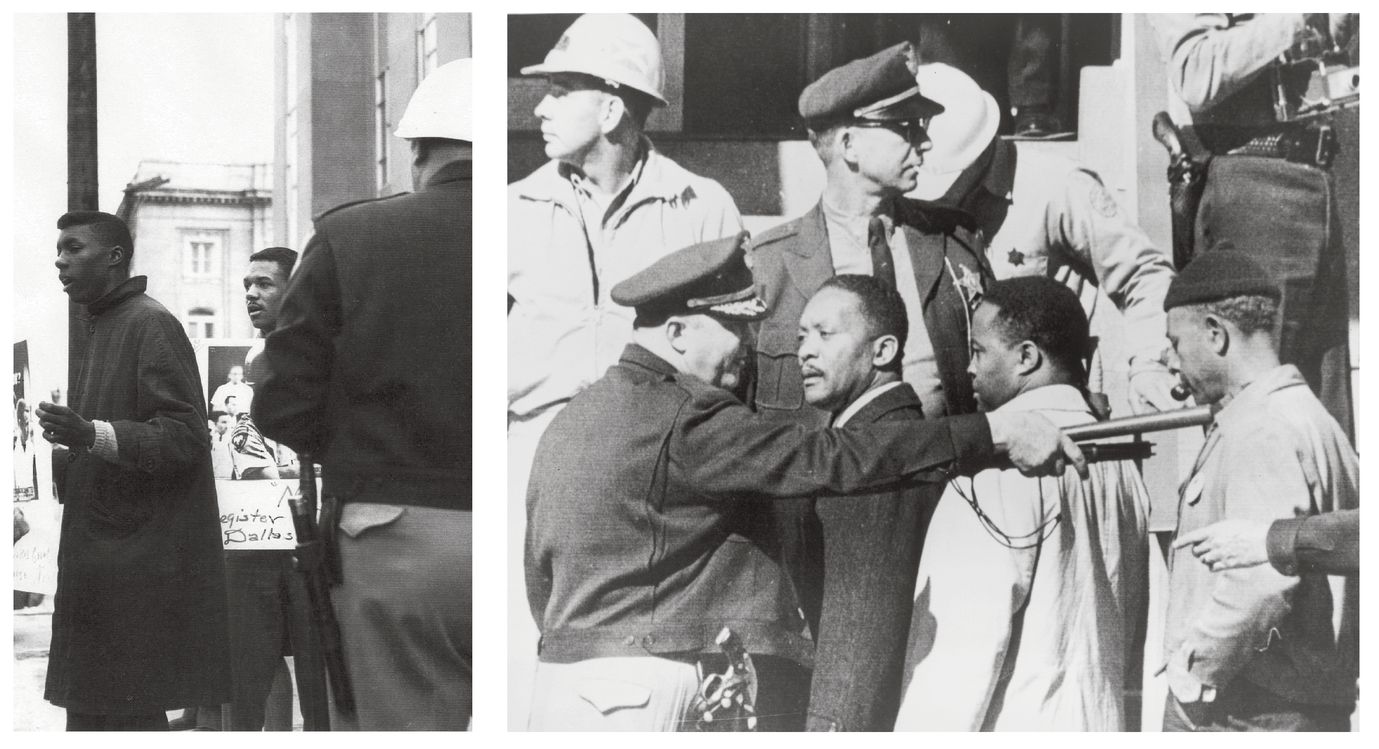

Charles Bonner explains to newsmen why he is protesting. Sheriff Clark looks on. RIGHT. Sheriff Clark sticks his billy club in a man’s neck as he orders waiting applicants to move away from the Dallas Courthouse. In the same hand, Clark holds an electric cattle prod.

Mrs. Boynton stepped back. She figured he had said it all. She left the courthouse and began to walk down the sidewalk. Sheriff Clark ordered her to join the line of people waiting to register. She refused and kept walking. There was no reason for her to be in line. Clark hated to be disobeyed. He lost his temper, pushed her roughly down the sidewalk into a patrol car, and arrested her.

The sheriff began shouting at the marchers. People jammed tightly together as deputies with nightsticks and electric cattle prods closed in on them. Sheyann wanted to run. “Baby, don’t be afraid,” said Mrs. Moore. “You’re young, but just don’t be afraid.”

Deputies herded them down Alabama Street toward city hall, shoving the marchers with their clubs and jolting them with the cattle prods.

More than sixty people were arrested, but Sheyann was able to slip away as the marchers were herded up to the second floor of city hall to the jail, to be held under “charges named later.”

The metal door clanged shut behind the marchers. It was frightening to be jailed, to hear the scrape of the key in the lock. But they were together. Humming, swaying, shoulders touching shoulders, they found their way into one freedom song, then another.

The next day a photograph of Mrs. Boynton’s arrest was carried by The New York Times and The Washington Post. Footage of her arrest dominated television news-casts. Across the United States, people were shocked by the sheriff’s rough treatment. Suddenly Selma had the national attention Dr. King sought.

Students cut school and held an impassioned meeting. Thanks to the Freedom Fighters, they’d learned to look at their lives very differently. As long as they were forced to live within strict limits imposed by violence and humiliation, they were still slaves. That had to change. “If death was the option to not being a slave,” said one student, Charles Bonner, “then so be it.”

Oh freedom

Oh freedom

Oh freedom over me!

And before I’ll be a slave

I’ll be buried in my grave

And go home to my Lord and be free

These were powerful words, put to deeply rhythmic music more than a century earlier by enslaved blacks. “That song was always very motivating to us,” said Charles. “We sang it with great passion.”

Still singing, the students marched to the courthouse. “Not that any of us were so brave we weren’t scared,” said Charles. “We were scared to death. We acted in spite of the fear.”

The sheriff arrested as many of them as he could. They were bused to the county work farm, overfilling the long, narrow buildings. Each building had only one metal toilet, one sink. People shared blankets, and once the bunks were filled, slept on the filthy floor. They were fed black-eyed peas, undercooked and gritty with sand. Sometimes they had plain grits with no salt or butter, or a boiled chicken neck. Deputies hid behind doors and jolted them with cattle prods as they went through. “They treated you miserable,” said Bobby.

But no one had to stay in jail long. Lawyers, using money from the SCLC coffers, worked around the clock posting bail, getting people out as fast as they could. “After the first time you go to jail,” Bobby said, “you get the fear out of you.” He’d keep marching.

Outraged by the students’ arrests, the black teachers had finally had enough—their students were showing more courage than they were. They met in the high school cafeteria and decided to march to the courthouse on Friday afternoon, January 22. One hundred and five teachers—nearly every member of the Selma Negro Teachers Association—decided: it was time to get registered or go to jail trying.

But Clark refused to even admit them to the courthouse. Looming above them on the stairs, fuming, he accused the teachers of making a mockery of the courthouse. Decades of training made it hard to look right at the burly sheriff as he lectured them. Their eyes flitted up to his face, then darted back down. But they stood their ground. Reporters lounged across the street, waiting for some action.

The white superintendent showed up and told the teachers to leave. They stayed. The superintendent conferred with Clark, insisting he hold back and make no arrests. It would be a disaster if Clark jailed the teachers, or if he had them all fired. Nearly every black kid in Selma would be on the loose, free to join the protests. After being shoved and prodded backward by the deputies, the teachers realized they weren’t going to be jailed, and they marched to Brown Chapel.

Students were waiting in three churches. They’d agreed to pack the jails if their teachers weren’t allowed to register. When the teachers solemnly walked in to Brown Chapel, everyone leaped up, applauding. Kids danced around, hugging and congratulating them. It was unbelievable that the teachers had defied Sheriff Clark and the superintendent. Never before had a group of black teachers marched together in the civil rights struggle in the Deep South. From Brown Chapel, they called the other two churches. All the students headed out, straight into the waiting arms of the deputies.

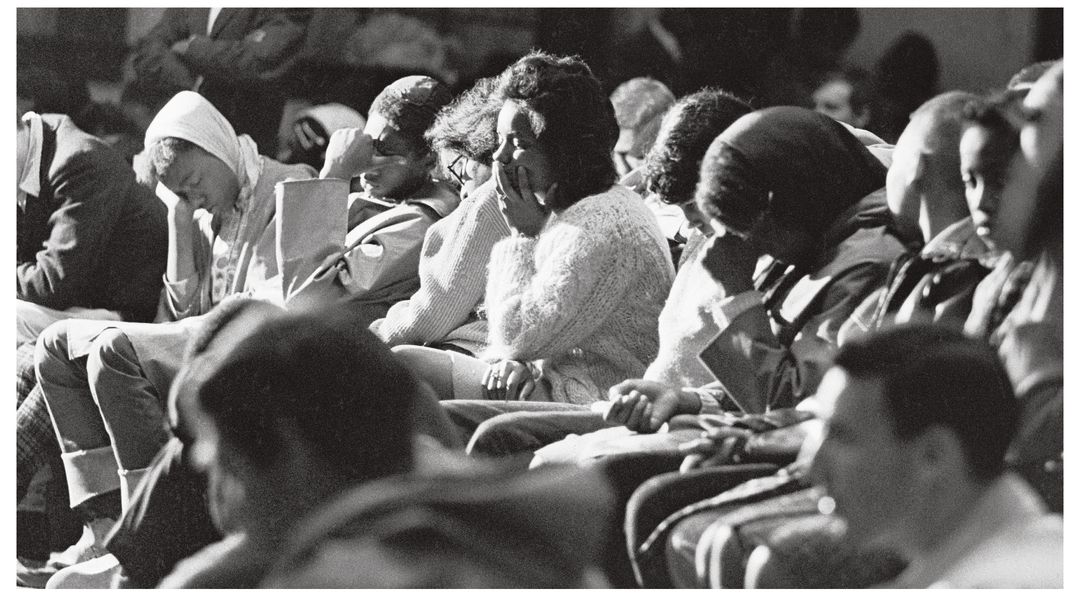

Teens often spent hours in church, singing, chanting, listening to speeches, and waiting. Some would leave the church to protest in the morning, and after they’d been arrested, a second group would head out.

February 1-17

ON MONDAY, FEBRUARY 1, Dr. King told an assembly at Brown Chapel that more than seven hundred people were gathered to march in nearby Perry County, expanding the movement. In another church in Selma, students were preparing to take off on their own march. “Even though they cannot vote,” King thundered, “they are determined to be freed through their parents.” He led 260 demonstrators out of Brown Chapel in a cold, drizzling rain. They headed up the street in a burst of freedom songs.

We’re gonna do what the spirit say do

We’re gonna do what the spirit say do

What the spirit say do we’re gonna

do, oh Lord

We’re gonna do what the spirit say do

They were all promptly arrested, including King and his trusted aide, Ralph Abernathy. They refused to be bailed out. The day after their arrest, Charles Mauldin led more than three hundred students to the courthouse. “We want to make them arrest us,“ he said. ”We’ll lock arms in front of the courthouse.“ They sang freedom songs until Sheriff Clark yelled, ”All of you underage are under arrest for truancy and the others for contempt of court. Turn that line around and let’s go.“

A policeman escorts teen marchers to jail following a demonstration in front of the courthouse, Selma 1965.

They were marched down to the old armory, a huge hangar with a cement floor. After processing the students at tables set up at one end of the building, deputies forced the boys to face the wall and stand on their tiptoes, their hands high up on the wall. The deputies paced behind the boys, reciting with relish what they’d do to them next: hang them from trees or drag them to death behind their cars. But the threats were empty. There were far too many reporters in town watching every move they made. The deputies settled for leaving everyone to spend the night on the cold floor.

Twelve-year-old Martha Griffin, a sixth grader, was one of the jailed students. “We had to sleep on the cement, with no cover,” she said. “And all those things [the guards] around there!”

Would she march again? “I’ll be right there,” she said. “I ain’t scared of those old things. They stuck my sister in the head with a pole and everything, but I’m not scared of them.”

Across the United States, people were shocked that Dr. King encouraged children to join in the civil rights struggle. “A hundred times I have been asked,” he said, “why we have allowed children to march in demonstrations, to freeze and suffer in jails, to be exposed to bullets and dynamite. The answer is simple. Our children and our families are maimed a little every day of our lives. If we can end an incessant torture by a single climactic confrontation, the risks are acceptable.”

On February 5, more than nine hundred students poured out of school to protest. In an effort to keep the kids off the streets, the all-white school board instituted a demerit system, threatening to expel kids who missed school, and warned parents they could be charged with misdemeanors if their children weren’t in class.

But the marches didn’t stop. Neither did the arrests. Prisoners were moved out of the surrounding jails as demonstrating adults and kids were crammed in.

The students kept their spirits up with their own lyrics to the civil rights song “If You Miss Me from the Back of the Bus.”

If you miss Governor Wallace

You can’t find him nowhere

Just come on over to the crazy house

He’ll be resting over there

If you miss Jim Clark

You can’t find him nowhere

Just come on over to the graveyard

He’ll be lying over there

After one arrest, Lynda spent eight days on a prison farm. But as soon as she was bailed out, she marched again. Sometimes jailors would wait until the middle of the night, then open the gates and tell the kids to go. From the Selma Prison Camp, it was several cold, dark miles to walk home, with no way to let their parents know where they were. They just prayed there was no one waiting in the dark to ambush them.

Sheriff Clark, frustrated he hadn’t stopped the marches, was increasingly agitated. On February 10, Charles marched with a group of students to the front of the courthouse. Arms linked, they stood singing in front of Clark and his deputies.

Instead of herding them off to jail as the students expected, Clark and his deputies brought around their squad cars and chased the students several miles out into the countryside. The deputies took turns jumping out of their cars, hitting and jabbing at them with nightsticks and cattle prods to keep them going. “You’ve been wanting to march,” the deputies shouted. “Now let’s go!”

“God sees you,” a fifteen-year-old said to a deputy, who clubbed him across the mouth. The students limped back into town, shaken and tearful, throwing up with exhaustion and fear.

Thirteen-year-old Cliff Moton was on the forced march. It made him mad to be run like that. But he’d kept going. “You’d be beat if you didn‘t,” he said. He’d been jailed earlier, but he was going to keep marching. “I want my parents to be able to get better jobs,” he said. “When I grow up, I want to be a carpenter. And be able to vote. I want my children not to have to be in this mess like we are in now.”

At first his mother didn’t want him to protest, afraid she’d lose her job. The day he got out of jail, she didn’t say anything to him. But by the next morning, she told him it was all right. Go on, she said.

Charles refused to let the forced march stop him. “You have to cut yourself off from your feelings,” he said. “You didn’t let yourself think about it or you would quit. We’d simply go back to the church and plan the next day.” He kept going, organizing, encouraging, leading groups of teenagers and kids out of the church to protest. “I’m proud of you,” he said to all of them after one march. “I used to wish I was white. Now I wish I was blacker.”

Watching their kids, more parents began to come to the meetings and join the marches, despite the risks. “The adults that came out anyway knew that their livelihoods were in danger, that they could be hung, killed in some horrible way—disappear forever, and their families would be left without any help,” said Joanne. “But yet they still got up and did it.”

If you cannot sing a congregational song at full power, you cannot fight in any struggle.... It is something you learn.

In congregational singing you don’t sing a song—you raise it. By offering the first line, the song leader just offers the possibility, and it is up to you, individually, whether you pick it up or not.... It is a big personal risk because you will put everything into the song. It is like stepping off into space. A mini-revolution takes place inside of you. Your body gets flushed, you tremble, you’re tempted to turn off the circuits. But that’s when you have to turn up the burner and commit yourself to follow that song wherever it leads. This transformation in yourself that you create is exactly what happens when you join a movement. You are taking a risk—you are committing yourself and there is no turning back.

When you get together at a mass meeting you sing the songs which symbolize transformation, which make that revolution of courage inside you.... You raise a freedom song.

—Bernice Johnson Reagon,

singer, songwriter, Freedom Fighter

Marches and arrests continued nearly every single day. At one point, Lynda was one of twenty-three girls crammed into a cell meant for two people in the city jail. The mattresses had been taken out, and the girls slept on the floor or the iron bed frames. By the third day, one girl was sick. Despite their pleas to the deputies for help, the girls were given brooms and told to clean the cell. Lynda grabbed hold of the broom handle, smashed out the small window overlooking Franklin Street, a black shopping area, and yelled for help.

The furious deputies rushed in. They made some ugly remarks, then herded all the girls into a sweat box—a small metal cell with no windows. When the door clanged shut behind them, it was pitch black. They were packed in so tightly no one could move. It quickly became stifling hot and humid, filled with their own stale, exhaled air. The dark, crowded box was terrifying. How long would they be left inside? Would they run out of air and suffocate to death? Lynda passed out.

Hudson High students sing at a meeting.

When she came to, jail inmates were carrying her and the other girls into the courtroom. She had no idea how long they’d been left in the sweat box. The judge told them all to write down their names and go home. “And for God’s sake,” he said as they left, “bathe!”

February 19-March 6

NERVES WERE INCREASINGLY frayed on both sides. Whites were tired of the constant marches, the “outside agitators,” and reporters in town. Freedom Fighters were dismayed that they’d made no significant progress, despite more than three thousand arrests. They decided to ratchet up the intensity of the demonstrations with a march in Marion, a town thirty miles northwest of Selma. This time it would be a night march, much more dangerous because of what could happen under the cover of darkness. Leaders knew it was risky, but night marches forced into public view the lawlessness always lurking below the surface.

At 9:30 P.M. on February 19, four hundred and fifty people set out from the tiny Zion Methodist Church in Marion. Whites rushed out from nowhere, smashing cameras and spraying black paint across TV camera lenses. Suddenly the streetlights were cut off. Police and state troopers stormed the marchers, swinging their nightsticks across shoulders, into vulnerable stomachs and skulls. The dark street filled with screams and shouts as the panicked marchers fled for safety.

Some people ran back to the church, others into any place they could find shelter from the flailing, cracking sticks. Eighty-two-year-old Cager Lee was hit in the head and ran, bleeding, into Mack’s Café.

Troopers rushed in after him, nightsticks swinging. Lee’s daughter and his grandson Jimmie Lee Jackson tried to protect him. Jackson was slammed against a cigarette machine and shot twice in the stomach by a state trooper. He staggered out the door and fell to the ground, where he lay unconscious and bleeding. More than three hours later he was finally taken to the hospital.

A man speaks into a megaphone at a night march in Selma, March 1965.

To protest the brutality in Marion, Selma students decided to hold a night march of their own. One hundred kids and teenagers gathered on February 23 at Brown Chapel. Waiting until the sun was low in the sky, they headed for the courthouse, trailed by reporters. A few blocks from the chapel, they were stopped by James Baker, Selma’s Commissioner of Public Safety. A moderate man, he didn’t want the students to reach the courthouse because he knew the forces gathered there: Sheriff Clark was lying in wait, along with his deputies, posse members, and seventy-five state troopers who’d been in Marion.

Baker raised his bullhorn and warned the oncoming marchers, in the interest of their own safety, to turn around. They knelt in prayer. A few minutes later, he diplomatically asked them to go peacefully back to their church. Quietly at first, then bursting into song, the students walked back the way they’d come. Just being out together at twilight, they’d publicly shown their defiance. As the sun set in a blaze of orange, the students were safely back in the church.

On February 25, Jimmie Lee Jackson died from his wounds. James Bevel, the brilliant, stormy preacher staying with Rachel’s family, was distraught over his death. He met with Jackson’s mother and his bandaged grandfather, who swore he was ready to march again right away. Bevel was used to the tremendous courage shown in the face of violence, but Jackson’s death hit him hard.

In the pulpit at Brown Chapel that Sunday, Bevel was lit up with anger and bitterness. He said he wanted to take Jackson’s body all the way to Montgomery and lay it on the state capitol steps where Governor Wallace worked. He wanted the governor to see the lethal violence he sanctioned.

It was a crazy, grief inspired idea. When Bevel calmed down, he realized that Jimmie Lee Jackson needed to be buried. But he also had a new idea. Speaking to a crowd of more than six hundred at Brown Chapel, he called on the congregation to march all the way to Montgomery, more than fifty miles away. “Be prepared to walk to Montgomery!” he shouted from the pulpit. “Be prepared to sleep on the highway!”

The idea caught on like wildfire. On March 3, Dr. King presided at Jackson’s funeral in Marion. More than a thousand mourners came to honor Jackson. They crushed into the tiny church, and stood outside in a light rain. After the service, they walked three miles behind Jackson’s casket in a cold, drenching rain to lay him to rest in Heard Cemetery. Dr. King announced that a march from Selma to Montgomery would take place the following Sunday, March 7.

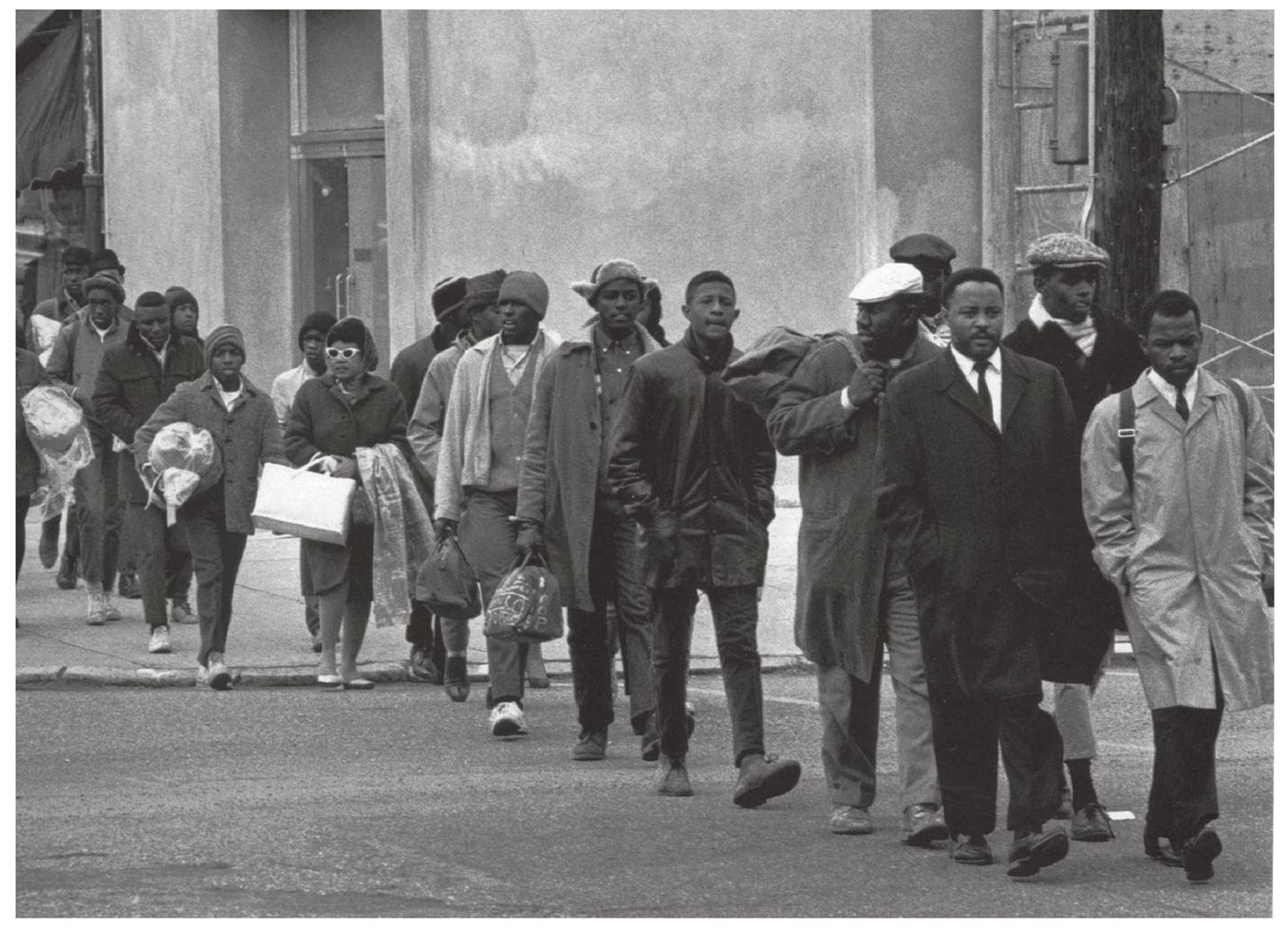

Marchers walk through downtown Selma, March 7, 1965, led by John Lewis, far right, and Hosea Williams, next to him. Sixth from the right, with his hands in his pockets, is Charles Mauldin.