BLOODY SUNDAY March 7, 1965

BY NOON ON March 7, hundreds were milling around Brown Chapel, waiting for the march to start. Rumors flew that the troopers would use tear gas on them. “Tear gas will not keep you from breathing,” a doctor explained. “You may feel like you can’t breathe for awhile. Tear gas will not make you permanently blind. It may blind you temporarily. Do not rub your eyes.”

Charles Mauldin reviewed protective moves with a group of kids and teenagers. Dodge any blows you could. If clubbed or kicked, curl into a tight ball and protect your stomach. If tear-gassed, drop to the ground to breathe, as the gas would slowly rise.

Rachel practiced with the others. She put her nose to the ground to breathe over and over again, with a growing sense of alarm. She couldn’t stop thinking about all the ways they could be hurt. Snipers could hide behind trees. Clark’s posse, on their huge horses, with their clubs and cattle prods, could chase them down. Bombs could be hidden in the church when they gathered, or flung through the windows.

Everyone was tense. Clark had put out a call for more deputies, and Governor Wallace had made it clear that he would stop the march. No doubt people would be jailed; some might even be injured. Dr. King was not there to reassure and inspire the marchers. Because of recent death threats, his advisors had talked him into staying away. He was in Atlanta, preaching at the church he co-pastored with his father.

The marchers set off around four in the afternoon, led by Freedom Fighters Hosea Williams and John Lewis. In case of trouble, another Freedom Fighter, Andrew Young, stayed behind at Brown Chapel. The marchers walked two by two down Sylvan Street, turned right onto Water Street, and headed for the bridge. No one sang or clapped. No one even talked. There was just the sound of their scuffling feet on the pavement. Mrs. Boynton and Charles were close behind Williams and Lewis. Not far behind them were Lynda, Bobby, and Sheyann. Lynda wanted her sister beside her, but Joanne lingered at the church, then joined the line farther back with friends. Rachel stood in front of Brown Chapel, watching the marchers leave, too afraid to join. Everyone was quiet, solemn, and anxious. What lay ahead?

A left turn took the marchers onto the Edmund Pettus Bridge, arching high up over the Alabama River, too steep for the marchers to see the other side. When Williams and Lewis hit the crest of the bridge, they came to a dead stop.

At the foot of the bridge stood a line of Alabama State Troopers in blue uniforms and helmets, blocking the road. To one side was Sheriff Clark’s posse, sitting high on their horses. White bystanders waited on the frontage road, shouting and jeering.

Williams and Lewis stepped forward, and the march resumed. “We were going to get killed or we were going to get free,” said one marcher.

Looking straight ahead, Charles didn’t let himself think about how vulnerable he felt. He had set his mind on Montgomery. “There’s a type of coolness that you develop, a steeling of the nerves so that you can accept whatever happens,” he explained. “There was no going back, and so you’re willing to accept whatever it takes. That’s what we were equipped with, just a sense of moral indignity.”

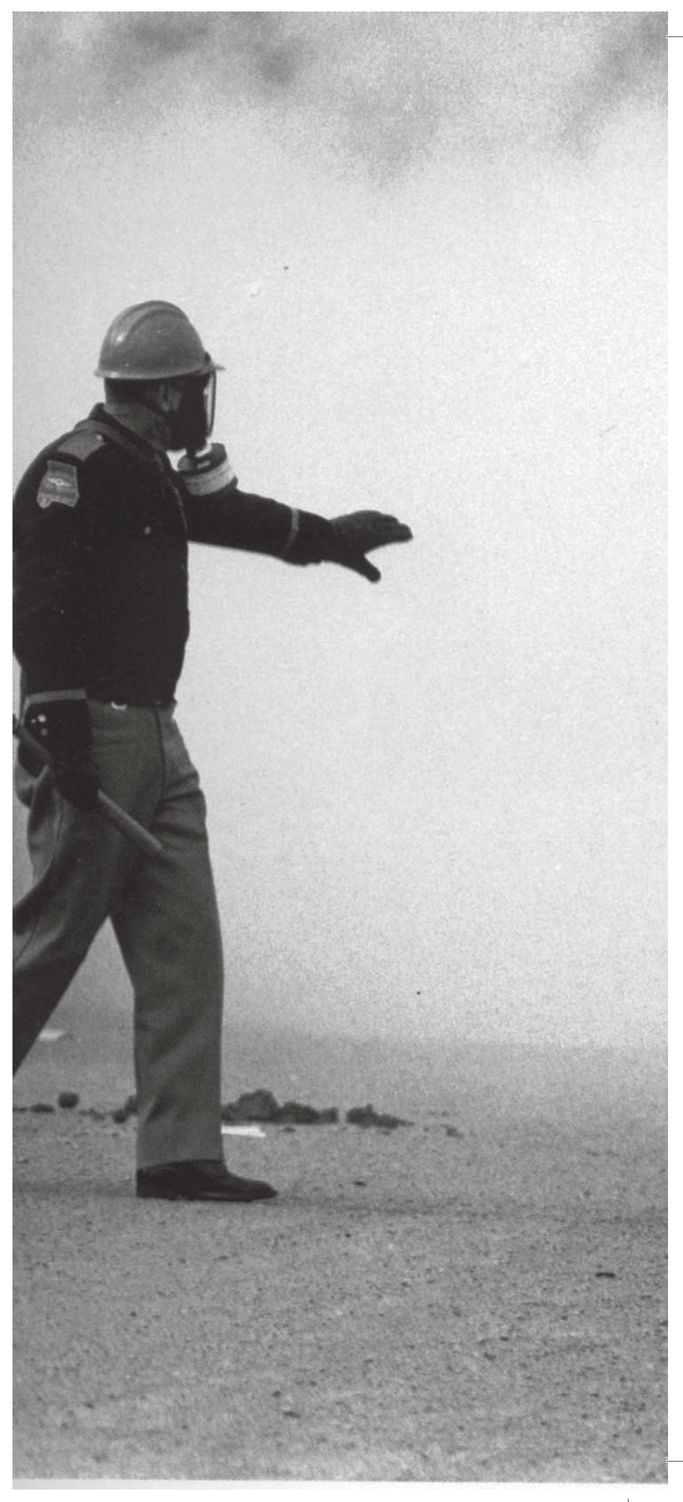

Troopers and posse pulled on gas masks, felt for the nightsticks hanging from their belts. Williams and Lewis walked to within fifty feet of the troopers and stopped. They were ordered to disperse in the next two minutes. “Go home or go to your church,” said a trooper through a bullhorn.

LEFT: Moments before the Alabama State Troopers attack, white onlookers eager to watch gather on the sidelines. Charles Mauldin is at the right under the Coca-Cola sign.

A burly trooper swings his billy club at John Lewis’s head. The blow left him hospitalized.

They stood.

One minute and five seconds later, troopers shoved into the marchers, swinging their clubs. Whites watching from the sidelines whooped and cheered. Charles heard John Lewis’s head crack as a billy club hit him. Lewis threw up an arm to protect himself, was struck again, and fell to the pavement.

Tear gas canisters crashed onto the bridge, spewing thick clouds of gas. Lewis felt strangely calm as he lay on the pavement. “This is it,” he thought. “People are going to die here. I’m going to die here.” Mrs. Boynton was struck in the head, blacked out, and fell to the ground.

Charles’s lungs were imploding from the tear gas. Desperate for air, he ran to a low area near the river where tear gas hovered a few feet about the ground. But a mounted posse forced him back to the bridge, into the gas. Bobby dodged the troopers, ran forward, and was cut off from the bridge, caught in the parking strip in front of several small businesses. “People were laying out, bleeding, coughing, crying,” he said. “We were pure defenseless.”

Lynda, still on the bridge, was enveloped in clouds of tear gas. A trooper grabbed her from behind, one hand at the back of her collar and one in front, and pulled her backward. Without thinking, she bit the hand in front, hard, and was hit over her eye with a billy club. The hands pushed her forward, and she was hit again on the back of her head. She stood and ran, chased deeper into the tear gas by the trooper.

The posse urged their horses forward into the running, falling, screaming marchers. Sheyann ran blindly back up the steep slope of the bridge, afraid she’d tumble off the bridge into the water or be trampled to death. Suddenly a Freedom Fighter scooped her up under the armpits and kept running up the bridge. Legs pumping, she yelled at him to put her down. He was running too slowly. But he held on tight until they were across the bridge before he let her go.

The waves of tear gas hit Joanne, still on the upslope of the bridge. People were running past her, screaming, followed by state troopers swinging their billy clubs. Even the horses, surrounded by terrified people, breathing tear gas themselves, were frightened. “They ran those horses up into the crowd and were knocking people down, horses rearing up, kicking people,” she said. “Blood was everywhere.” Joanne saw a dazed woman step in front of a horse and get knocked to the ground, her head bouncing on the pavement. Joanne fainted.

Panicked marchers ran back to the Carver Homes, chased by the posse, who were beating and whipping any marchers they could reach. “They would lean over the horse and hit you as hard as they could,” said Bobby. “It was so cruel.” He made it back across the bridge, dodging uniformed Selma firemen who were grabbing people and holding them for the posse to hit.

Wearing gas masks, troopers use their billy clubs to force protestors back into the choking, blinding cloud of tear gas.

When Joanne groggily came to, she was lying in the back of a car parked beside the bridge. Lynda was bending over her, crying and crying, her tears dropping down on Joanne. When Joanne came fully awake, she realized it wasn’t tears but blood from two gashes in Lynda’s head dripping on her.

Lynda was taken to the hospital, where doctors and nurses worked feverishly to care for more than one hundred patients laid out on every surface, even the floor of the employees’ dining room. Around her, people’s bloody lacerations were stitched shut, broken bones were set, and tear gas washed out of irritated, burning eyes. It took more than thirty stitches to close Lynda’s wounds, but the pain was nothing compared to the searing realization she had about the white men who’d attacked them. “It was pure hatred,” she said. “They came ready to do what they did. They would go to any means necessary to keep us subservient and docile. These people beating us, they took pleasure in it.”

As battered, coughing children staggered home, furious fathers grabbed their guns. Charles’s mother stopped her husband as he tried to get out the door. At Brown Chapel, Andrew Young had to talk sense into men who wanted to fight back. The .32 or .38 shotguns they had were no match for automatic rifles and ten-gauge shotguns. There were at least two hundred guns out there filled with buckshot. “You ever see what buckshot does

to a deer?“ Young asked. Most of them had. They realized it would be suicidal to try to fight back.

That evening, everyone crept into Brown Chapel. The smell of tear gas, clinging to people’s clothes and hair, hung heavily in the room. Sheyann came in the back door and stood and looked at everyone for a long time before she sat down. It wasn’t that people were afraid: it was as if they didn’t care to try any longer. The hope had been beaten out of them. It was, she said, “like we were slaves after all and had been put in our place by a good beating.”

Some people sat in stunned silence; some were crying and softly moaning. After a while, a slow, quiet humming mixed in with the moaning. At first it wasn’t clear what the song was, it was so slow, like the sound of a funeral song. Then the humming and moaning got louder, and picked up speed.

Ain’t gonna let nobody, Lordy, turn me ‘round ...

Turn me ‘round ...

Turn me ‘round ...

Ain’t gonna let nobody, Lordy, turn me ‘round ...

Keep on a-walkin’

Keep on a-talkin’

Marching up to Freedom land.

Soon the song was coming out loud and strong and pure. New verses were made up as they sang. Ain’t gonna let no horses turn me ‘round ... no tear gas ... no sheriff ... no troopers.... People leaped to their feet, clapping and swaying, singing some more. They took their defeat and sang their way back to strength. They’d stayed committed to nonviolence. They were willing to go out again and face state troopers and mounted posses with whips and tear gas and clubs. The music made them bigger than their defeat, bigger than their fear. It wove them together, filled them once more with courage and strength.

While the marchers were in the church, footage taken by news crews was being broadcast across the country on all three major television networks. ABC interrupted a Nazi war crimes movie, Judgment at Nuremberg, to show viewers the violence in Selma. People were shocked to see composed, nonviolent Americans being attacked by heavily armed troopers on horses. ABC let the footage run for nearly fifteen minutes. Forty-eight million viewers watched in growing disbelief and horror as men, women, and children desperately fled for safety.

In Atlanta, Dr. King was distraught that he hadn’t been with the marchers. He immediately sent telegrams to more than two hundred religious leaders sympathetic to the civil rights movement, asking them to come to Selma for a peaceful march on Tuesday.

A woman tends to Amelia Boynton, who lies unconscious on the ground at left.