TURN AROUND TUESDAY March 9

A THOUSAND EAGER, anxious people crammed into Brown Chapel Monday night for a mass meeting. Clergy had been arriving all day and sat in the front pews. At 10:30 Dr. King finally arrived. The crowd leaped to its feet and burst into song:

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord:

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored;

He hath loosed the fateful lightning of His terrible swift sword:

His truth is marching on.

For nearly five minutes they sang and clapped before settling down to let Dr. King speak. Grateful to the newly arrived clergy, he asked them to stand and introduce themselves. They were Catholic and Protestant, Baptist and Jewish. There were priests and nuns, pastors and rabbis. This was bigger than any difference in worship: this was a time for all to respond to Dr. King’s call.

“Thank God we’re not alone,” Dr. King said to each of them after they introduced themselves. He gave a heartfelt tribute to the marchers who had endured beatings and tear gas, then he roused the crowd for Tuesday’s march. “We must let them know that if they beat one Negro they are going to have to beat a hundred,” he thundered, “and if they beat a hundred, then they are going to have to beat a thousand.”

Late that night Dr. King was told that a federal judge was issuing a court order prohibiting the march until further notice. The order put Dr. King in a terrible bind. He had no qualms about violating state and local laws that were rigged against blacks, but this was different. In all his civil disobedience he’d never defied a federal order. He was counting on the federal courts to uphold civil rights legislation.

Informed of the court order, President Johnson was adamant that Dr. King needed to wait. Marching now, in defiance of the order, could be used to justify renewed violence from Governor Wallace’s state troopers. Aides for the president worked deep into the night, phoning and visiting King, asking him to reconsider. President Johnson even had his Attorney General call Dr. King, begging him to be patient and postpone the march until there was a hearing. Dr. King listened thoughtfully, then replied, “Mr. Attorney General, you have not been a black man in America for the past three hundred years.”

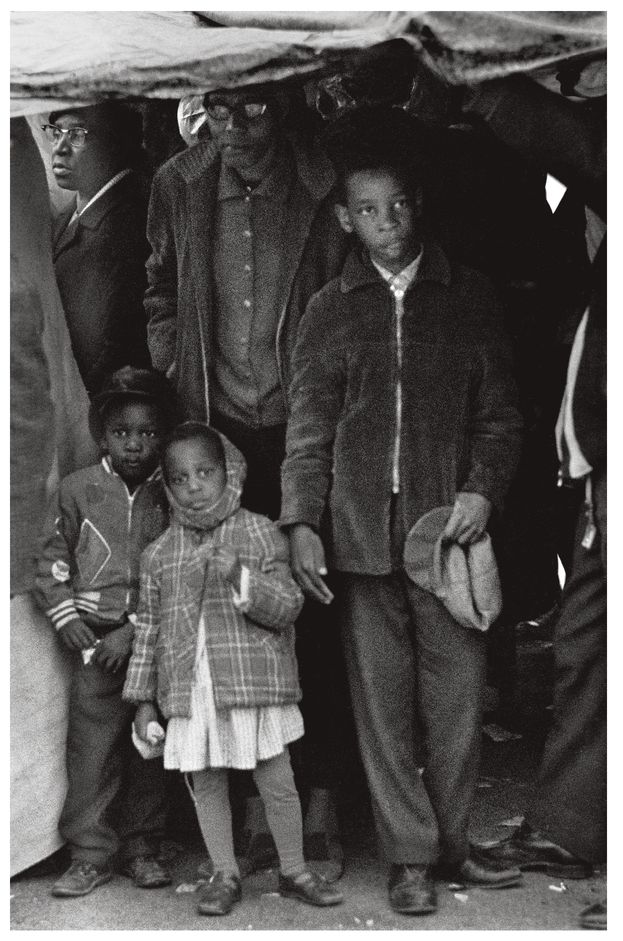

Despite the cold weather, people waited outside on the grounds of the Carver Homes to hear Dr. King speak, March 9, 1965.

King arrived at Brown Chapel Tuesday morning with a heavy heart, unsure what to do. More than two thousand people crowded around the chapel, including most of Hudson High’s students. The mood was incredibly tense as everyone readied themselves for a repeat of the violence of Bloody Sunday. But they weren’t going to back down: the time for justice was this day, this moment.

King disappeared into the parsonage of Brown Chapel to strategize and pray with his aides. People milled around the grounds of Carver Homes, waiting. At two o‘clock, Dr. King emerged and stood on the stairs of the chapel. The crowd moved in closer to listen. “I do not know what lies ahead of us.” King’s voice rolled across the crowd. “There may be beatings, jailings, tear gas. But I would rather die on the highways of Alabama than make a butchery of my soul.”

Joanne was afraid to go, but she got in line close to the front with Lynda. “I held Lynda’s hand this time,” Joanne said. “She didn’t have to worry about me bein’ anywhere else but with her.” Despite his own deep misgivings, their father had encouraged them to march. “If you don’t go,” he said, “it means they won.” Bobby, Charles, and Sheyann all joined the march as it left Brown Chapel.

By 2:30, Dr. King was leading the marchers up the arch of the Edmund Pettus Bridge and down the other side, where he was ordered to halt. One hundred troopers stood blocking the road, twice the number present on Bloody Sunday.

Dr. King asked for permission to pray, which was granted.

The marchers knelt, and Dr. King led them in prayer. As they stood back up, they were confronted by an incredible sight. The barricades had been pulled away and the troopers had stepped to the side of the road.

King was stunned.

Was it a trap? If Dr. King led the marchers forward, would he be leading them into a bloodbath? Were the troopers trying to humiliate him, undermine his leadership by offering a path he couldn’t afford to take? Behind him two thousand marchers stirred, ready to move forward.

Dr. King suddenly wheeled around and shouted at them to go back. The marchers were confused. Dr. King shouted a second time for them to turn around, then walked back up the bridge. Andrew Young stood at the bottom of the bridge, motioning people to turn around. Slowly, the marchers turned in a tight circle and walked back across the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

Emotions ran the gamut in the crowd of U-turning marchers. Many were euphoric that they hadn’t been forced into the powerful blows of the troopers’ nightsticks. Others felt betrayed, sure King’s decision was a low point of moral courage for the whole civil rights movement.

Back at Brown Chapel, the crowd surged and floundered, filled with the energy to march and nowhere to go. Sheyann, relieved and excited there’d been no violence, slipped quickly between adults on the lawns of the Carver Homes, finding clergy from out of town, leading them by the hand to her apartment for a cup of coffee and a chance to sit down. One of the ministers, James Reeb, talked with her mother and promised he’d be back later for a cup of coffee after a meal in town at Walker’s Café.

He never returned. Leaving the café with two other ministers, they were ambushed by four white men who clubbed Reeb in the head before vanishing into the darkness. Reeb was taken to the hospital in Birmingham, where he lay in a deep coma.

Dr. King stood on a razor’s edge of self-doubt about his decision to turn the march around. He asked the out-of-towners to stay, sure the judge would grant them the right to march as soon as he reviewed the facts surrounding Bloody Sunday. Some disgusted out-of-towners left immediately, dubbing the march “Turn Around Tuesday,” but others bunked down on floors in the Carver Homes and waited.

Protestors gathered on the wide, blocked-off street outside of Brown Chapel after the assult on James Reeb. When it rained, they stood under makeshift shelters and tarps.

The next morning the mayor put up a wooden barrier across the street less than a block from the church and forbade all marching. Deputies, troopers, and Clark’s posse backed him up. Protestors quickly dubbed it the “Berlin Wall” and hundreds of them kept up a constant vigil in the rain, singing freedom songs, chanting, and praying. On Thursday, March 11, Reeb died. More than a thousand kids cut school Friday and again Monday to stay out on the streets and protest.

On March 15, eight days after Bloody Sunday, protestors came in from their rain-soaked vigil to watch President Johnson address Congress in a live, televised broadcast. Dr. King and John Lewis had been invited to Washington, D.C., to hear the president speak in person, but decided to stay in Selma with other SCLC aides to watch on TV.

“I speak tonight for the dignity of man and the destiny of democracy,” Johnson began, in a speech that had been written just minutes earlier.

“Rarely, in any time, does an issue lay bare the secret heart of America itself,” he said. “The issue of equal rights for American Negroes is such an issue.... What happened in Selma is part of a far larger movement which reaches into every section and state of America. It is the effort of American Negroes to secure for themselves the full blessings of American life.”

Listeners in Congress and across America were astonished. Johnson had just claimed Selma as a crucial battleground for civil rights, and thrown his full, public support behind it. Johnson went on to say that in two days he would be sending to Congress “a law designed to eliminate illegal barriers to the right to vote.” His speech was interrupted over and over again by applause.

“Their cause must be our cause too. It is not just Negroes, but all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice.

“And we shall overcome.”

Protestors often stood for hours with linked arms singing Freedom Songs while they waited for news of James Reeb’s condition. These nuns came to Selma after seeing footage of Bloody Sunday. Joanne Blackmon is on the far right in the light coat, and Sheyann Webb is squeezed between two sisters.

King’s aides burst into cheers as the president evoked their anthem, the heart and soul of the civil rights movement, and adopted it as his own. Only Dr. King was silent. Lewis looked over at him and saw a tear slide down his cheek.

On Wednesday the federal judge officially issued his ruling on the right to march. When he compiled all the facts, he found an “almost continuous pattern ... of harassment, intimidation, coercion, threatening conduct, and sometimes, brutal mistreatment” by state and local lawmen, “acting under the instructions of Governor Wallace.” He granted Dr. King the right to lead a march from Selma to Montgomery.

The same day, President Johnson introduced a voting rights bill into Congress. With the federal government behind him, Dr. King immediately set a new march date: Sunday, March 21. And this time, they were going all the way to Montgomery.