DAY ONE Sunday, March 21

Goal: David Hall’s Farm

EXACTLY TWO WEEKS after Bloody Sunday, Dr. King led the procession from Brown Chapel. Religious leaders from across America walked beside him. Lynda’s father had been adamant that she couldn’t go all the way to Montgomery. He didn’t want her to take such a big risk. But she had enlisted five respected, wise women who promised to watch out for her on the march, and he’d relented. She wanted Governor Wallace to see he hadn’t hurt her spirit. “I wanted him to see my shaved head and I wanted him to see my face,” she said, “‘cuz it was still swollen and I still had bandages on it.” Used to being away in jail, she packed extra underwear, shirts, and food. Charles and Bobby were enlisted as marshals for the whole march—to help get under way each day, assist those who needed it, and keep an eye out for trouble. Joanne, Sheyann, and Rachel were going for only the first day.

Near the front of the line was Cager Lee, the eighty-two-year-old grandfather of Jimmie Lee Jackson, whose death had sparked the march. “Yes, it was worth the boy dying,” Cager Lee said. “He took me to church every Sunday, he worked hard. But he had to die for something. And thank God it was for this!”

Marchers flooded down Sylvan Street onto Alabama Avenue and made a wide turn onto Broad Street. The line kept swelling until three thousand people were streaming toward the Edmund Pettus Bridge in the early spring sunshine. Some carried suitcases and bedrolls.

Despite the joyful marchers’ songs filling the air, organizers’ nerves were strung tight. At a black church in nearby Birmingham, a ticking bomb made of forty-eight sticks of dynamite had been discovered, set to go off at noon. Demolition experts defused it, then rushed to disarm three more deadly bombs in town.

Above the line of marchers, two large military helicopters circled low, on the lookout for anything threatening. Governor Wallace had refused to provide protection, forcing President Johnson to federalize the Alabama National Guard, putting them under his control. For further safety, Johnson ordered 2,000 regular army troops to help guard the route.

Brisk winds swept over the marchers as they headed up and then down the arch of the Edmund Pettus Bridge. As they passed the site of Bloody Sunday and Turn Around Tuesday, they broke into cheers and singing.

Paul and Silas bound in jail

Had no money for da go de bail

Keep your eyes on the prize, hold on

Hold on, hold on

Keep your eyes on the prize, hold on

Songs rippled down the line of marchers. The line was so long, three or four songs could be sung at the same time without overlapping. In the adjacent lane, army jeeps, cars full of reporters, medical vans, water trucks, and flatbeds loaded with portable toilets drove slowly up and down the road.

“How could you ever think a day like this would come,” said Cager Lee as he walked. He was marching for freedom in an area bound by the chains of slavery for his family. “My father was sold from Bedford, Va., into slavery down here. He’d tell how they sold slaves like they sold horse and mules. Have a man roll up his shirt sleeve and pants so they could see the muscles, you know.”

At a rest stop seven miles out, Sheyann and Rachel saw Dr. King and rushed up to greet him. Buses were parked nearby, ready to take most of the marchers back to Selma. They had reached the point where Highway 80 narrowed from four lanes to two, and Dr. King had been ordered to limit the march to three hundred people until the highway widened to four lanes again near Montgomery. A few of the teenagers who weren’t chosen to keep going protested the twenty-two whites who got to continue marching. Andrew Young had to point out that including whites offered some protection against violence, and that it was meant to be an inclusive march.

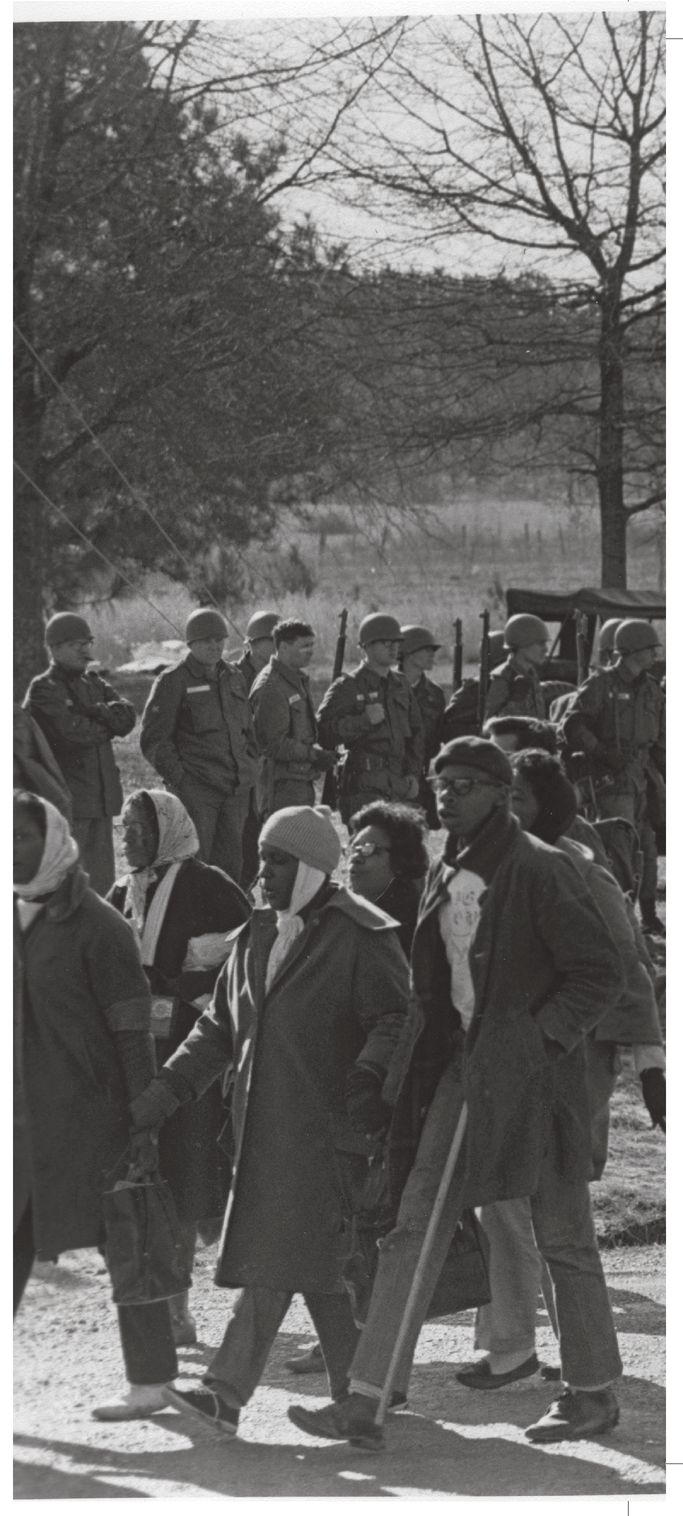

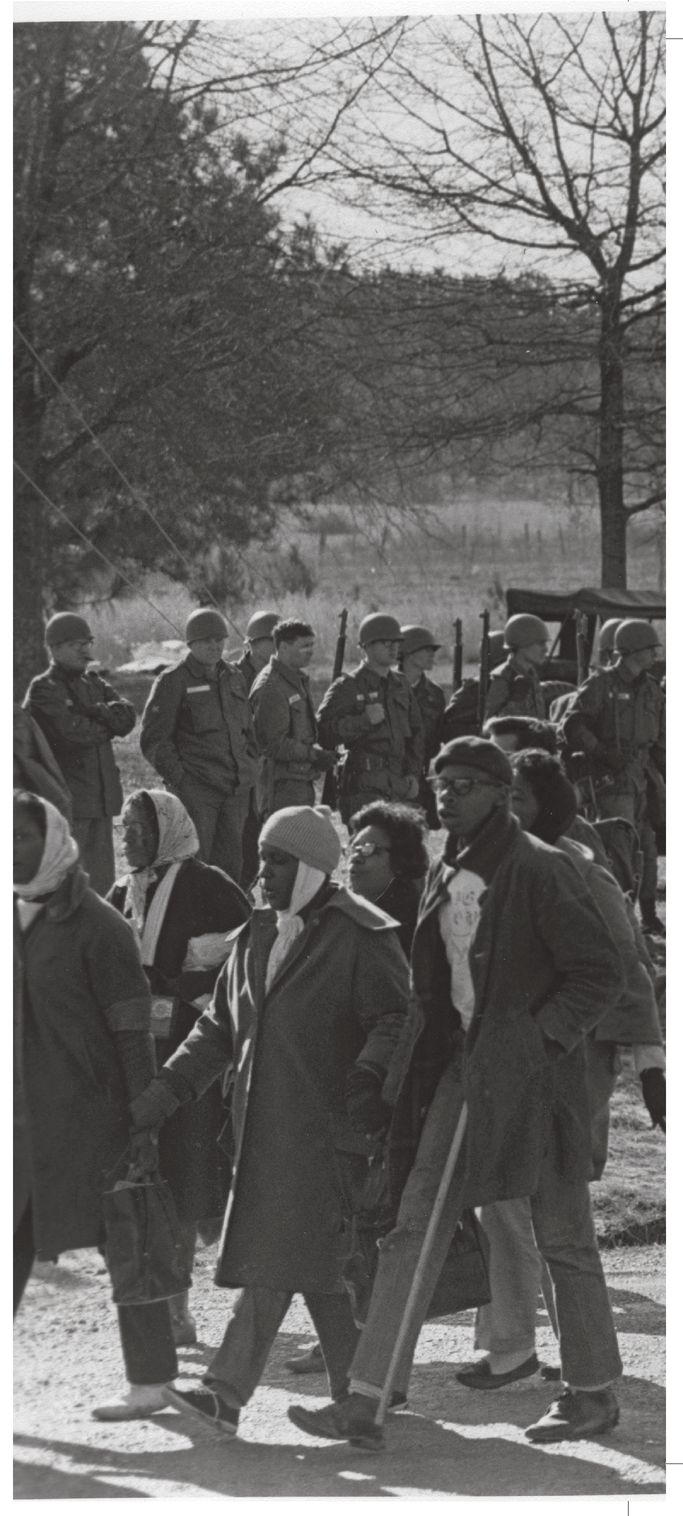

National Guardsmen, ordered by President Lyndon Johnson to protect the marchers, stand watch as the protestors leave Selma.

Along with other tired marchers, Sheyann, Rachel, and Joanne clambered onto the buses for the ride back to Selma. Three hundred and eight marchers, most under twenty years old, and one-third female, turned off the highway onto a narrow country road leading to a farm. Four huge tents had been set up in the field. As evening fell, a large yellow rental truck drove up and unloaded shiny new metal garbage cans filled with dinner: spaghetti, pork and beans, and cornbread.

As soon as the sun disappeared, temperatures plummeted, and people headed into the tents. A generator growled in the background, fueling a few bare lightbulbs in each tent. Hissing kerosene heaters took the edge off the cold.

The students weren’t ready to settle down. They stood three and four deep around a lead singer, singing and swaying through gospel and freedom songs. The leader suddenly shouted out, “One more time and really cool it.” He sank down, lightly snapping his fingers. Around him voices softened as people crouched, swaying, whisper-singing.

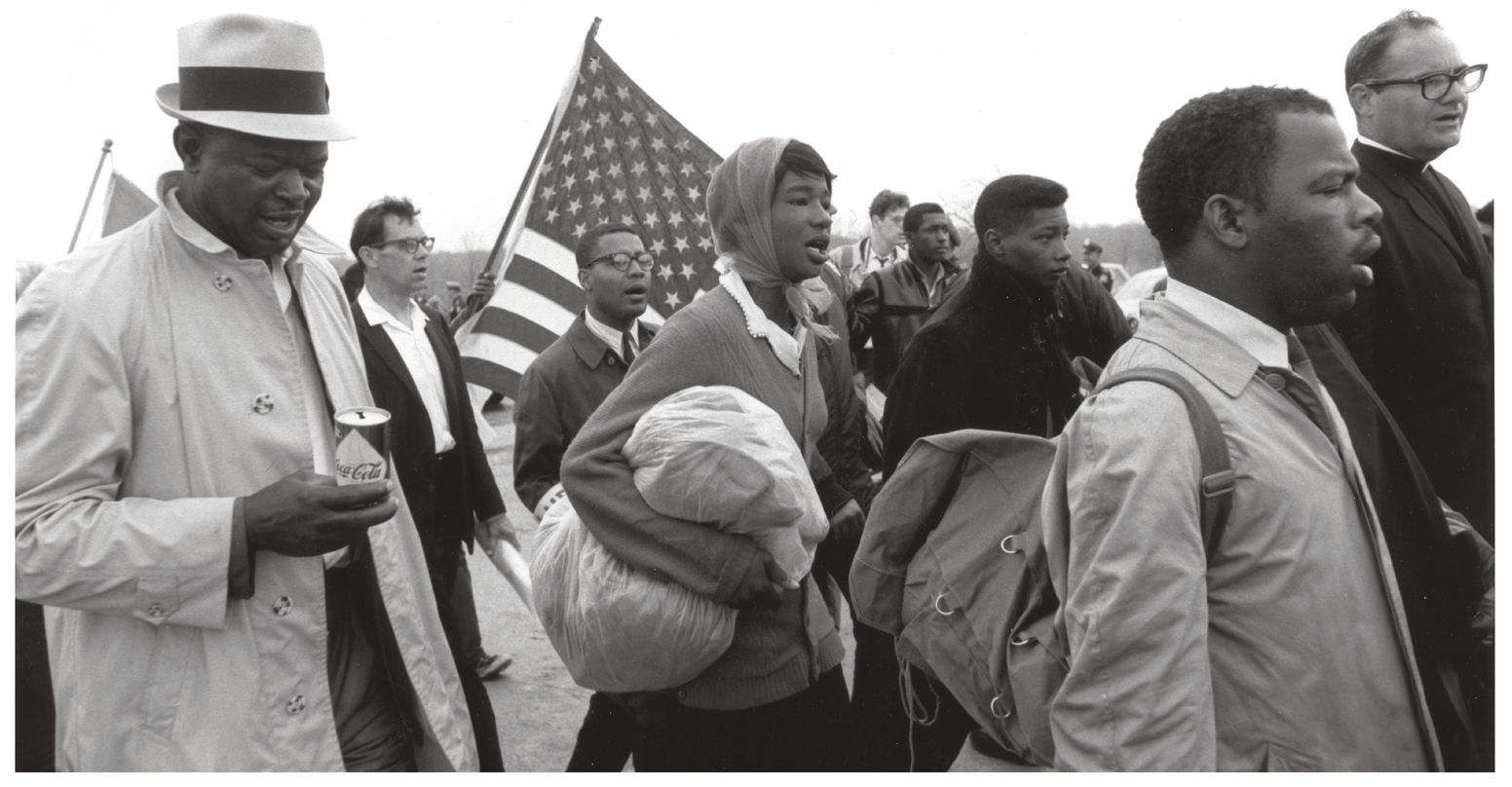

John Lewis, far right, packed a few belongings into his knapsack. Twenty-year-old Doris Wilson carried hers in a waterproof bag under her arm. She’d been fired from her twelve-dollar-a-week job in a school lunchroom for taking part in the demonstrations.

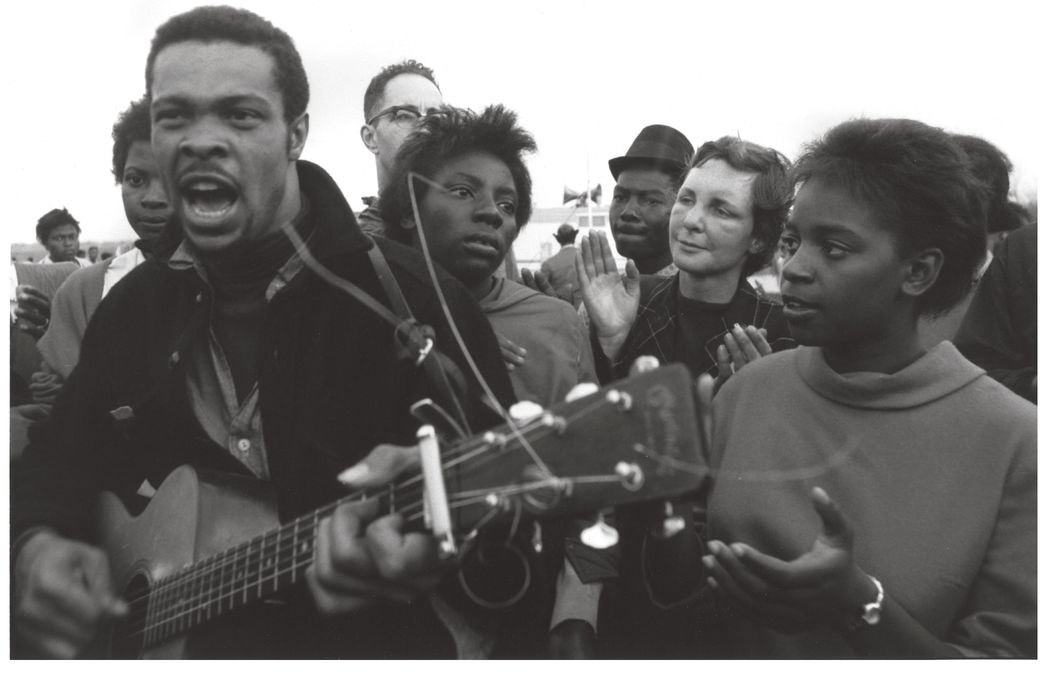

At the end of the day’s walk, marchers sing freedom songs.

“Jump!” shouted the leader and everyone shot up into the air and shouted out and sang some more until the singing blended with laughter and quiet talk.

Outside, the National Guardsmen assigned to night duty lit small, crackling fires for warmth, making patches of yellow light in the dark. Inside, the heaters sputtered and ran out of kerosene. Bone-chilling fog crept in. There weren’t enough blankets, coats, and sleeping bags to go around. Some people gave up trying to sleep and went outside, lit a fire in a trash barrel, and stood around it, shivering and talking quietly.

They were anxious about tomorrow, when they’d cross into Klan-infested Lowndes County. Instead of wide-open fields, they’d be walking through swamps and dense patches of woods. Most of the marchers lay in the tents, too tired to talk, too cold to sleep, listening as the students from Selma sang softly far into the night.