DAY TWO Monday, March 22

Goal: Rosa Steele’s Store

THE COLD, STIFF marchers were routed out of their tents early for the seventeen-mile trek to the next campsite. A heavy frost crackled under their feet as they shuffled forward in the chow line, where gluey oatmeal and watery coffee were being served out of the garbage cans.

As Lynda came out of the tent, she saw three National Guardsmen standing in front of a jeep, the butts of their guns perched on their waists, bayonets pointing up at the sky. She realized with a shock that they were just like the men who’d beaten her on the bridge. “It looked like they were staring straight at me,” she said, as Bloody Sunday rushed back to her. “I thought they were there to kill me—to finish off the job they’d started.” She started screaming.

Some people thought Lynda should be sent back to Selma, but the women looking out for her disagreed. They surrounded her, listening, soothing, talking. “They knew they couldn’t send me back as scared as I was,” Lynda said. “It would have destroyed me.” A one-legged white man, Jim Letherer, told Lynda that before he’d let anyone hurt her, he’d lay down his life for her. She was astonished. “What kind of person would I be,” she thought, “if I let him die for me?” Her determination rushed back. She was going all the way to Montgomery.

Marchers walk under gathering storm clouds. A recognizance plane from

the National Guard circles overhead, on the lookout for trouble.

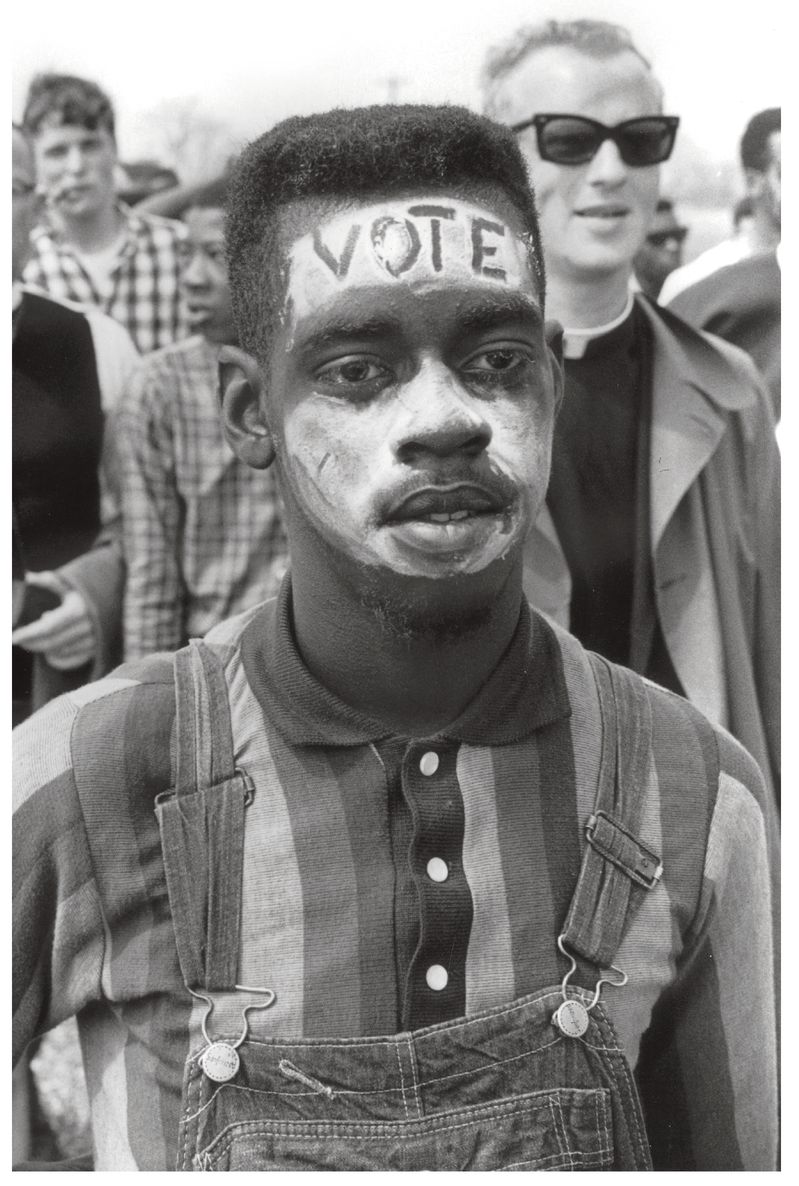

Bobby Simmons used thick white sunscreen to write on his forehead.

When the march crossed into Lowndes County, military protection increased. Eight new army jeeps went ahead of the marchers, along with a demolition team to check under the bridges for explosives. The helicopters circled protectively as the marchers entered the gloomy swamp, crossing Soapstone Creek safely, and then Big Swamp Creek. They sang their way past the draping Spanish moss, the murky water thick with mud and floating algae.

It was a relief when the swamp gave way to pasture-land where small weathered shacks stood in the big fields, green grass pushing up through the stubble of last year’s corn crop. Marchers shed sweaters and sweatshirts as the spring sun bounced off the asphalt. Soon they came to Trickem Fork, a cluster of houses with one church and a school. They’d made it nearly halfway to their goal: twenty miles from Brown Chapel, they had thirty more miles to go.

New rumors spread fast as they reached the end of day’s march: a man had been spotted planting a bomb under a road bridge; twenty white men were seen prowling through a nearby field, armed with guns. But the gossip was quickly squelched: it was just a boy who had hopped off his bike to relieve himself under the bridge; army demolition experts had been checking the area around the campsite.

As people ate dinner and settled down for a second night on the ground, the medical team busily treated exhausted marchers with blistered feet. Dr. King gave a short press conference, and everyone readied themselves for another cold, damp night.

At midnight, Charles was woken up by a frightened teenager who’d slipped into the tent. He was thinking about starting a youth movement in his high school and wanted to know what motivated Charles. “You really believe in non-violence?” the boy asked Charles.

“I do,” Charles said. “I used to think of it as just a tactic, but now I believe in it all the way.” He wasn’t worried about more violence for his own sake. It would only be a test of his commitment. “It’s easy to talk about non-violence,” he said, “but in a lot of cases you’ve got to be tested, and re-inspire yourself.” His only concern was for the others from Hudson High School, making sure they were all safe.

By 2 A.M. everyone in the campsite was asleep except for the night guards and two shortwave radio operators in a truck. They were in constant touch with Selma, where busloads of people were still pouring into town.

The marchers camped on Rosa Steele’s property, near her small general store. Asked if she was worried about retaliation from local whites, Mrs. Steele replied, “I’m not afraid. I’ve lived my three score and ten.”