plus

A Badly Behaved Rabbit,

Henry Ford’s Food Fetish, A Dose of

Devil’s Porridge, The Amazing Career

of Cat’s-Eyes Cunningham, and

A Royal Embroidery Contest

Large, naked raw carrots are acceptable as food only to those who lie in hutches eagerly awaiting Easter.

FRAN LEBOWITZ

Beatrix Potter’s Peter Rabbit, certainly the most famous rabbit in literature, didn’t eat carrots. No, really. He didn’t. Once he wiggled under Mr. MacGregor’s garden fence, he gorged on lettuces, French beans, and radishes, and then, feeling sick, he went off in search of parsley. At that point he rounded a cucumber frame, encountered the justifiably enraged Mr. MacGregor, and spent most of the rest of the book running. That evening, still without a carrot in sight, his well-behaved siblings, Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cottontail, got blackberries and milk for supper, while the reprehensible Peter was put sternly to bed with a dose of chamomile tea.

Rabbits will eat carrots but, frankly, carrots don’t seem to be all that high on the rabbit food list. Their preferred vegetables are peas, beans, and beets, and if you grow any or all of these, the only way to keep rabbits from munching up the lot is to put a two-foot fence around your garden. Alternatively you can sprinkle the perimeter with dried blood or fox urine — or you can get a ferret. Not that these are guarantees. Rabbits are pushy, persistent, and tough.

People, on the other hand, not only eat carrots, but apparently adore them. Each of us consumes about twelve pounds of carrots a year (up from a mere four annual pounds in 1975); and kids, who turn up their noses at squash and spinach, routinely list carrots among their vegetable favorites. Historically, foremost among American carrot fans was industrialist Henry Ford, whose passion for vegetables was perhaps second only to his fondness for the automobile.

Ford was anti-milk (“the cow is the crudest machine in the world”) and anti-meat (he promoted soybeans in lieu of beef and oatmeal crackers as a substitute for chicken), but he was devoted to the carrot which, he was convinced, held the secret to longevity. At one point he was the guest of honor at a twelve-course all-carrot dinner, which began with carrot soup and continued through carrot mousse, carrot salad, pickled carrots, carrots au gratin, carrot loaf, and carrot ice cream, all accompanied by glass after glass of carrot juice.

One story holds that Ford became interested in the painter Titian when his son Edsel donated a Titian painting (“Judith and the Head of Holofernes”) to the Detroit Institute of Arts. It wasn’t the artist’s work that interested him; it was the fact that Titian had reportedly lived to be ninety-nine. He wanted to know if Titian ate carrots.

The first carrots, botanists believe, came from Afghanistan and were purple. Scrawny, highly branched, and unpromising, these wine-colored roots belonged, like their plump cultivated descendants, to the Apiaceae family, some 300 genera and 3,000 species of aromatic plants commonly known as umbellifers. As well as the crunchy carrot (Daucus carota), the Apiaceae include celery, parsnips, anise, caraway, chervil, cilantro, cumin, dill, fennel, lovage, parsley, and poison hemlock — this last, known in Ireland as “Devil’s porridge,” an infusion of which killed Socrates. Characteristically, the umbellifers have hollow stems: Yann Lovelock in The Vegetable Book (1972) describes how the stalks of wild parsnip were once used as straws for sipping cider and weapons for shooting peas.

The ancestral carrot probably looked very much like Queen Anne’s lace, the ubiquitous wild carrot of present-day fields and roadsides. The cultivated Greek and Roman carrots were probably still branched — a witchy characteristic referred to by modern breeders as “a high degree of ramification” — but were most likely larger, fleshier, and less bitter than their wild relatives. Experiments in the late nineteenth century by French seedsman Henri Vilmorin demonstrated the relative ease with which primitive farmers could have developed the cultivated carrot. Starting with a spindly-rooted wild species, Vilmorin was able to obtain thick-rooted equivalents of the garden carrot in a mere three years.

The conical root shape characteristic of carrots today seems to have shown up in the tenth or eleventh century in Asia Minor, and may have reached Europe in the twelfth century by way of Moorish Spain. No one, however, seems to have rushed to adopt it: John Gerard, in the sixteenth century, remarks that as nourishment goes, the carrot is “not verie good,” although botanist John Parkinson, author of Paradisus in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (1629), who seems to have liked it better, says it can be “eaten with great pleasure” if boiled in beef broth. The roots, he added, are “round and long, thicke above and small below,” and come in either red or yellow, while the dark green foliage, in autumn, turns red or purple, “the beautie whereof allureth many Gentlewomen oftentimes to gather the leaves and stick them in their hats or heads, or pin them on their arms instead of feathers.”

The emperor Caligula, who had a fun-loving streak, once fed the entire Roman Senate a feast of carrots in hopes of watching them run sexually amok.

Carrot Clarinets and Pumpkin Drums

The Vienna Vegetable Orchestra consists of a group of eleven musicians whose concerts around the world are performed on instruments made of fresh vegetables, such as carrot flutes, recorders, and clarinets; pumpkin drums; and leek violins.

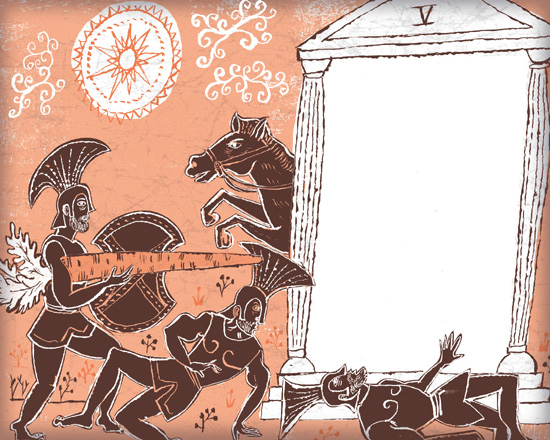

The primitive purple, violet, red, and black carrots owed their color to anthocyanin, a pigment that dominated the carrot world until approximately the sixteenth century, when a pale yellow anthocyanin-less mutation appeared in western Europe. It thus must have been an anthocyanin-laced purplish carrot that Agamemnon’s soldiers legendarily munched (presumably quietly) inside the Trojan Horse “to bind their bowels,” and that Greeks on the home front used to concoct an aphrodisiacal potion or philtron. Like any vegetable even vaguely resembling a penis, the carrot was thought to be a passion promoter. Devious Roman soldiers boiled carrots in broth to release the sexual inhibitions of their female captives, and the emperor Caligula, who had a fun-loving streak, once fed the entire Roman Senate a feast of carrots in hopes of watching them run sexually amok.

The purple carrot quickly fell from favor with the advent of the yellow and, later, orange varieties. The cultivated purples, though tasty, turned an unappetizing muddy brown when cooked, which put off even the most stolid of chefs. The aesthetically appealing orange carrot is said to be a late-sixteenth- or early-seventeenth-century development of the Dutch, who were the dominant European carrot breeders. Some evidence for this comes from the sudden appearance of orange carrots in period oil paintings: Dutch painter Joachim Wtewael’s “Kitchen Scene” (1605), for example, a detailed portrayal of a crowded and active kitchen complete with kids, dogs, cats, and a flirtation going on in the corner, features a large bunch of orange carrots sprawled, dead center, on the floor.

From the first orange original, Dutch growers soon produced the even deeper-colored Long Orange, a hefty carrot intended for winter storage, and the smaller and sweeter Horn. The Horn was further fine-tuned to yield, by the mid-eighteenth century, three breeds of orange carrot varying in earliness and size: the Late Half Long, the Early Half Long, and the smaller Early Scarlet Horn. Collectively, these 200-year-old Dutch carrots are the direct ancestors of all orange carrots grown today.

Carrots owe their orange to carotenoids, a collection of some five-hundred-odd yellow and orange pigments that function in plants to protect the all-important green chlorophyll from sun damage. About 10 percent of carotenoids are also vitamin A precursors, and beta-carotene — the most prominent carotenoid in carrots — is one of these. In the human digestive tract, beta-carotene is clipped in half by a helpful enzyme to form two molecules of vitamin A, also known as retinol.

No matter what your grandma told you, carrots won’t give you full-fledged nocturnal vision, any more than bread crusts will make your hair curl.

Raw or Stewed?

A single orange carrot provides the average adult with more than his or her recommended daily allotment of vitamin A. In terms of beta-carotene, however, the carrot cooked is far more forthcoming than the carrot raw. Crunched down à la Bugs Bunny, raw carrots release only about 3 percent of their total beta-carotene to the human digestive system. In boiled carrots, where the cooking acts to break down the root’s thick cell walls, up to 40 percent is released; and blended or juiced carrots release up to 90 percent.

Vitamin A plays a number of essential roles in the human body, among them the support of cell growth and reproduction and the regulation of the immune system — but it is perhaps best known for its effect on eyesight. In the retina of the eye, vitamin A binds to a protein (opsin) in the rod cells to form the visual pigment rhodopsin, which allows us to see — more or less — in the dark. In fact, the first hint of vitamin A deficiency is impaired dark adaptation (“night blindness”), and a severe or prolonged lack of vitamin A can lead to permanent blindness.

No matter what your grandma told you, however, carrots won’t give you full-fledged nocturnal vision, any more than bread crusts will make your hair curl. The carrot-based night vision hype can be traced to the Battle of Britain in World War II, when Britain’s newly installed radar network, which effectively tracked incoming German bombers, began to give a distinct advantage to the fighter pilots of the Royal Air Force.

During World War II, innovative home front housewives produced carrot toffee, carrot marmalade, carrot fudge, and a drink called Carrolade made from crushed carrots and rutabagas.

Legendary pilot John Cunningham, nicknamed “Cat’s Eyes” for his reputed ability to see in the dark, was the first person to shoot down an enemy plane with the aid of radar, and he soon went on to chalk up an impressive record of kills. The RAF, in an attempt to distract German attention from the bristling radar towers along the British coast, spread the story that Cunningham and his fellow night-flying pilots owed their success to a prodigious diet of vision-enhancing carrots. It’s not clear how the carrot con went down with the German high command, but the British civilian population swallowed it, in the belief that eating carrots would help them navigate in the blackout.

Although carrots can’t give you bona-fide night vision, they can, if you eat enough of them, turn you yellow. This syndrome, known clinically as carotenemia or carotenosis, results from the deposition of carotene pigments in the subcutaneous fat, just beneath the skin. Though visually somewhat startling, carotenemia seems to be physically harmless and disappears within a few weeks if the victim lays off carrots.

Carotene also gives cream its rich yellowish hue. In the seventeenth century, cows fed on the champion Dutch carrots were said to yield the richest milk and the yellowest butter in Europe, which in turn was held to be responsible for the famous rosy-cheeked Dutch complexion. Butter makers in colonial America, starting with less well-fed cows, often colored their butter after the fact by adding carrot juice to the churn.

As well as beta-carotene, carrots are also high in minerals, notably potassium, calcium, and phosphorus. In 2008, Kendal Hirschi and his team at Baylor College of Medicine in Texas created a genetically engineered high-calcium “super carrot,” capable of delivering to the eater over 40 percent more calcium than the ordinary carrot. Super carrots may eventually help stave off such conditions as brittle bone disease and osteoporosis.

Carrots also contain a lot of sugar. A single 7½-inch carrot contains some seven grams of carbohydrate, most of it — as in honey — in the form of fructose and glucose. Carrot carbs were made much of by the British Ministry of Food during World War II, when sugar was essentially unobtainable. The Ministry’s “War Cookery Leaflet 4,” devoted to the preparation of carrots, included recipes for carrot pudding, carrot cake, and carrot flan. Under the urging of the government’s vegetable-promoting “Dr. Carrot,” a gigantic carrot tricked out in a lab coat and top hat, innovative home front housewives produced carrot toffee, carrot marmalade, carrot fudge, and a drink called Carrolade, made from crushed carrots and rutabagas.

Because of their lip-smacking sweetness, carrots historically have been used in desserts. A recipe for carrot conserve — a sweet jam — survives in the fourteenth-century Menagier de Paris. The conserve, whose carrots are referred to as “red roots,” also contains green walnuts, mustard, horseradish, spices, and honey. John Evelyn’s 1699 Acetaria: A Discourse of Sallets contains a recipe for a distinctly unsaladlike carrot pudding, a luscious-sounding mix of cream, butter, eggs, sugar, nutmeg, and grated carrot. The Irish, who doubtless found carrots a welcome relief from a relentless diet of potatoes, called them “underground honey.”

Even sweeter than the carrot is the related parsnip, Pastinaca sativa, which Ogden Nash, not a parsnip lover, compared damp-ingly to an anemic beet. Historically, it fared better: cheap, sugary, and substantial, the parsnip was a prime entrée in the Middle Ages, especially during the lean days of Lent.

The parsnip, like the bustle, began to fall from favor in the nineteenth century when, along with the Jerusalem artichoke, it was ousted from gardens by the more versatile Irish potato. Pre-potato, however, it was a garden staple: the rich ate parsnips in cream sauce and the poor ate them in pottage. John Gerard and Sir Francis Bacon both put in a good word for them; and Sir Walter Scott wrote sardonically that fine words don’t butter any parsnips, meaning that flattery is worth diddly-squat.

Most parsnips are long, pale, funnel-shaped roots, a sort of oversized khaki-colored carrot. (Round turniplike varieties, introduced to the United States in 1834, never really caught on.) The large meaty types known as hollow-crown parsnips were developed in the Middle Ages; still grown today, these have a saucer-shaped depression at the top of the root (the “hollow crown”) from which sprout the stems and leaves. Parsnips contain, root for root, about twice as much sugar as carrots, most in the form of sucrose, the sugar of sugarcane.

Aunt Hannah, having passed through port and rum, hit the parsnip wine, which led her to sing “a song about Bleeding Hearts and Death, and then another in which she said her heart was like a Bird’s Nest.”

Historically, the sugary parsnip has been boiled down into syrup and marmalade and, with the help of a little yeast, brewed into beer and wine. One early nineteenth-century source directs hopeful winemakers to boil twelve pounds of sliced parsnips, strain through a sieve, add loaf sugar and yeast, and then age for twelve months. Modern winemakers, however, according to biologist (and parsnip fan) Roger Swain, opt for aging up to ten years, and a lot of wine connoisseurs suggest never, under any circumstances, taking the stuff out of the cask.

Drunk, however, it seems to be effective: in A Child’s Christmas in Wales, Dylan Thomas’s susceptible Aunt Hannah, having passed through port and rum, hit the parsnip wine, which led her to sing “a song about Bleeding Hearts and Death, and then another in which she said her heart was like a Bird’s Nest.”

The sweeter the parsnip, the more efficient the fermentation process — which means that winemakers should harvest their parsnips in the spring. Many plants, including parsnips, cabbages, and potatoes, sweeten after exposure to temperatures below 50 degrees F (10 degrees C). As early as the first century CE, Pliny the Elder commented on the phenomenon: “Turnips are believed to grow sweeter and bigger in cold weather,” and “With any kind of cabbage, hoarfrosts contribute a great deal to their sweetness.”

Low-temperature sweetening occurs in leaves, shoots, and roots of responsive plants. The sugar content of cabbages doubles after thirty days in the cold; overwintered parsnips contain nearly three times more sucrose by weight than their autumn-harvested buddies.

No satisfactory explanation yet exists for this sweetening process. One hypothesis suggests that the increased sugar acts as a cryoprotectant, a species of natural antifreeze. A similar explanation has been advanced to account for the increased spring sugar content of some tree saps, like that of the syrup-generating sugar maple.

Carrots and parsnips are biennials. The starches and sugars of the fat storage roots are meant to support the development of flowers and seeds in the second year of growth. Permitted to progress to year two, carrots produce lacy compound umbels on two- to six-foot stalks, similar to the flowers of Queen Anne’s lace. The largest flower, which ripens first, is called the king umbel, followed by a lesser array of side umbels, from all of which develop carrot seeds.

The edible taproot, for which gardeners routinely forfeit the aesthetic delights of carrot flowers, consists of a central core of vascular tissue and an outer layer called the cortex, composed of storage tissue. In the carrot, as increasing amounts of starch are accumulated, the central core pushes outward, maintaining a two-part pattern, which is why the carrot in cross-section looks like a slice of hard-boiled egg. In the beet, in contrast, vascular and storage tissue are laid down in alternate rings, like those of a tree trunk, while in the radish and turnip, vascular and storage cells are indistinguishably intermixed.

Queen Anne, the story goes, challenged her ladies-in-waiting to make a piece of lace as fine as the flower of the wild carrot.

The taproots of today’s garden carrots average five to eight inches long. These are weenie by ancestral standards. Nineteenth-century growers boasted of two-foot roots, a foot or more in circumference at the thickest, and weighing up to four pounds. Amelia Simmons, in her 1796 American Cookery, after a discussion of the superiority of the yellow carrot over the orange and the red, advises the “middling sized” carrot for cooking, by which she means a hefty vegetable a foot long and two inches across at the top. She recommends it as an accompaniment for veal, though it is also “rich in soups” and “excellent with hash.” Carrots in Mary Randolph’s Virginia Housewife (1824) require three hours of boiling, which implies a vegetable of substantial size.

The carrot arrived in North America with the first settlers. The Jamestownians planted them between tobacco crops; and John Winthrop, Jr., included “Carrets” on his seed list of 1631. Carrots figured in the earliest of American seed advertisements: in 1738, one John Little offered orange carrots for sale along with his other “new garden seeds”; in 1748, “Richard Francis, Gardner, living at the sign of the black and white Harre at the South end of Boston” offered the gardening public carrots in a choice of orange or yellow. Jefferson grew carrots in several colors at Monticello.

From all of these widespread colonial gardens, the carrot promptly escaped and reverted to the wild. The ubiquitous American Queen Anne’s lace of fields and country roadsides descends from ex-cultivated escapees.

The Queen of these lacy flowers is said to be Anne of Denmark, wife of England’s James I and an expert needle-woman. Queen Anne, the story goes, in an attempt to alleviate the mind-crushing boredom of court living, challenged her ladies-in-waiting to make a piece of lace as fine as the flower of the wild carrot. The Queen herself, not surprisingly, won hands down, and the flower was rechristened in her name. Less romantically, it is known as bird’s nest or devil’s plague.

On both sides of the Atlantic, the 1870s were a banner decade for carrots, ushering in both the Danvers carrot, a dark orange, medium-long variety with exceptionally high yields, developed in Danvers, Massachusetts, and the Nantes carrot, named for its town of origin in France. Burpee’s 1888 Farm Annual neglected the Nantes in favor of the equally French Chantenay (“of more than usual merit”) and Guerande (“of very fine quality”) — but reserved special praise for the homegrown Danvers, variously described as “handsome” and “first-class.” Also offered by Burpee were the Early Scarlet Horn and the related Golden Ball, a stumpy little vegetable that looked less like a carrot than a deep-yellow radish.

French seedsmen Vilmorin-Andrieux, in The Vegetable Garden (1885), diplomatically mention both the Danvers and the Nantes varieties along with some twenty-three other carrots, in a range of shapes and sizes. Impressive among them is the English Altringham carrot, whose bronze or violet roots measured over twenty inches long.

Garden carrots today generally belong to one of four major types: Imperator, Danvers, Nantes, or Chantenay. In general, Imperator and Danvers carrots are long and pointed; Nantes and Chantenay carrots, shorter and blunt; but the vast number of carrot cultivars available today tend to blur distinctions. Most carrot eaters agree that Nantes and Chantenay types are best for eating raw, while Danvers types — known for “broad shoulders” — are best for slicing and popping in stew.

It’s safe to say, however, that there’s a carrot out there for everybody. In fact, the online World Carrot Museum, an extraordinary collection of all things carrot, includes a list of common carrot varieties that includes at least one for (almost) every letter of the alphabet, from the New Zealand Akaroa to the (good for juicing) Zino.