Darkus continued reading, looking and listening for any clue.

Darkus felt his brain was being bombarded—not by positive messages but by negative ones. Still he read on.

Darkus understood his father’s frustration with the book: its shallow pursuit of a superficial world, its reliance on expectation and luck instead of the hard-earned achievement of the individual, which was what good detective work depended on. Agitated, he read on.

Darkus stopped. Something about the last sentence caught his attention. He went back and read it again, slowly, letting the peaks and troughs of the letters burn themselves into his visual cortex.

There was more to the text than first appeared.

“Dad?”

Knightley opened one eye, to determine whether it was worth interrupting his rest. “What is it, Doc?”

“Can I use your microscope?”

Curious, Knightley prized himself from his chair and walked to the shelf that held his forensic microscope: a white metal apparatus with two eyecups, a slide, and a rotating head with multiple lenses. He plugged it into a small TV monitor. The monitor flickered to life, then snowstormed. Knightley smacked it sharply, and the snowstorm switched to a display menu.

“Proceed,” said Knightley.

Darkus held up The Code and quickly tore out the page he’d been reading. Knightley winced. He’d seen many dead bodies and witnessed many brutal crimes, but there was still something violent about ripping a book.

“Allow me to offer up a theory,” said Darkus.

“Continue.”

Darkus held up The Code. “If the book isn’t inherently ‘evil,’” he began, “and its message—while morally questionable—isn’t specifically telling the reader to commit a crime . . . then the answer must lie within the text itself.”

“Wrong,” said Knightley with conviction. “If that was true, the text would affect every reader the same way. Instead it only affects a select few.”

“Let’s have a closer look.” Darkus placed the torn page under the lens. A blurred image appeared on the monitor.

“Try this.” Knightley rotated the lens head to a different magnification.

The printed words appeared on the monitor in black and white. Darkus positioned the page to capture the line that had caught his attention.

“There,” said Darkus.

Knightley’s eyes narrowed; his nostrils flared. Then his face unwound again.

“Just a printing error. The typeface is corrupted.”

“Exactly.”

“There’s no method to it. No logic.”

“Look again,” said Darkus.

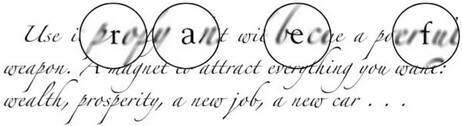

Knightley peered into the image on the monitor, genuinely puzzled. Then he moved even closer, the tip of his nose almost touching the screen as his eye picked out the odd letters, which now stood out boldly to him:

Knightley’s eyes lit up. “Certain letters are printed in a strange, slightly modified typeface, but not every time,” he noted. “Only when it spells r-a-e-f. You’re saying there’s a code in The Code?”

Darkus nodded. “The same letters are repeated in the same typeface, in the same order, every second paragraph.”

Knightley snatched the page from under the microscope and stared into it like he was staring into a void. The letters R, A, E, F stood out like the optical illusion of a face hidden in an abstract picture, or the haunted face of Jesus appearing on a household object. One moment it was ordinary, the next it was the vessel for a private secret.

Knightley’s eyes widened. Suddenly he wasn’t looking at a page of text, but a swirling vortex with the same four letters repeated over and over.

“r-a-e-f,” said Knightley. “If there’s a meaning, it’s lost on me.”

“You’re reading left to right,” said Darkus. “Try reading right to left.”

Knightley blinked, astonished. “Fear,” he said under his breath.

“Precisely.”

“But no one reads right to left,” argued Knightley. “Not in the Western world.”

“Not true. A boy in my class was diagnosed with attention deficit disorder. He had trouble focusing on words and reading basic sentences. He said it was just the way his brain worked.”

“Involuntary saccadic eye movements,” said Knightley, quoting the medical term. “Some people can’t read consistently left to right. Their eyes have a tendency to run ahead or lag behind instead of traveling smoothly. In theory, that would make them susceptible to the hidden message.”

“The theory’s sound,” said Darkus. “The message only affects readers whose brain chemistry prohibits them from giving the book their full attention.”

“Once again, Doc, you’ve out-reasoned me.”

“I like to believe there’s always a rational explanation rather than a supernatural one,” said Darkus.

“Then tell me this . . . ,” said Knightley. “What makes the reader commit the crime?”

Darkus stared into space for a moment, turning the problem over in his mind like a sphere spinning suspended in an electromagnetic field; he observed it from every angle. “The continual repetition of the word ‘fear’ would create feelings of anxiety and paranoia in the reader, without them ever consciously knowing why. For Lee Wadsworth it manifested as his worst phobia: the fear of insects. For every reader it would be different.”

Darkus turned the problem over in his mind again, divining the answer from the soup of possibilities, negatives and positives, zeros and ones.

“You’re right,” Darkus agreed. “He had to have received an instruction.” A thought struck him like a bolt of lightning.

“What is it?” asked his father.

“Underwood has a stutter.”

“Yes.”

“Lee Wadsworth said the voice that told him to rob the bank cut in and out. And you said Underwood practiced hypnosis.”

Knightley realized where he was heading. “Underwood delivered the instruction.”

“But how would Underwood contact them? And how would he know which readers to recruit?”

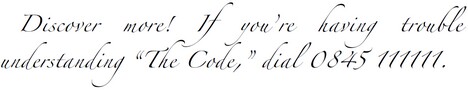

Darkus quickly leafed through the book until he reached the back cover. At the bottom of it, a tagline read:

“The readers contact him.” Darkus reached for his phone and dialed the number.

They both listened as an automated female voice said: “Your call is being transferred. Please hold.” The line continued ringing for another thirty seconds.

Then an automated male voice announced: “Please leave a message with your name and telephone number after the tone.”

Darkus ended the call. “That’s how Underwood locates them,” he said. “The readers are perfect criminals. They have no knowledge of one another . . . or of who gave them the orders.” He realized, not without irony, “They would think the book told them to do it.”

He looked to his father for congratulation, but Knightley’s face had suddenly clouded over, appearing more troubled than ever. Darkus opened his mouth to speak as Knightley held up a finger and urgently pointed to the doorway.

A single white dove had entered the room, strutting across the carpet, blinking at them impassively. It looked like some kind of sentinel, or sign.

“Dad . . . ? What’s it doing here?” whispered Darkus, lacking a suitable explanation for what was in front of him.

“Bogna!!” Knightley cried out. For once, there was no response. “Stay back, Doc. It’s a message.”

Knightley knelt down and picked up the bird, finding a small paper scroll attached to its neck. The dove flapped its wings as he gently removed the scroll and unfurled it. The message read simply:

![]()

“Doc,” said Knightley, feeling his heart thudding in his chest. “I want you to go and find the best hiding place you can.”