Chapter 15

Hot-Button Issues for Mormons

In This Chapter

Understanding Mormon views on race and gender

Understanding Mormon views on race and gender

Coming to terms with a colorful history

Coming to terms with a colorful history

Dealing with the fruits of free speech

Dealing with the fruits of free speech

Facing troublesome sexual issues

Facing troublesome sexual issues

Like any human organization, Mormonism has its fair share of seeming gray areas, contradictions, and conflicts that, for some members, require patience and faith to negotiate. Many of the challenges result from this young religion’s dynamic, evolving nature, which leaves some people wanting to return to earlier ways, some struggling to reconcile the past with the present, and some trying to speed up the process of change.

This chapter looks at some of the key areas where Mormons and outside observers experience the most disagreement or lack of resolution. Certainly, the faith’s zigzagging approach to race is troubling to many. Although Mormon views on gender roles have stayed fairly consistent — liberal for the 19th century, but conservative for the 21st — some people are dissatisfied with them. Mormon history and scripture are riddled with twists and pitfalls, and challenging voices from both inside and outside the faith continually clamor to be heard. Finally, many Mormons are still struggling to come to terms with homosexuality and polygamy (though not usually at the same time).

Race and Gender Controversies

Non-Mormons who happen to catch a session of LDS General Conference on the DISH Network may be startled by what they see: a parade of grandfatherly white men who run the show, codify the doctrine, and make all the decisions about the direction of the Church. In an age when women and African Americans have ascended to the top of many other Christian organizations, the current leadership of the LDS Church seems like a throwback to a less-enlightened age.

Of course, the situation isn’t that simple, and what goes on in the upper echelons of leadership in Salt Lake City sometimes takes a while to catch up with the reality of Mormon life, which is increasingly international and multiracial. In this section, we explore the controversies that Mormonism has brought about with its leadership practices and also look at the role that women and blacks play in the Church.

Black and white and shades of gray

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has experienced a lot of controversy in its history (for more on that, see just about any chapter in this book), but perhaps none so painful and long lasting as that caused by the Church’s 150-year denial of the priesthood to its black members. As you see in this section, the issue wasn’t fully resolved in 1978, when the Church finally reversed that priesthood denial.

Going back to the beginning

In the early days of the Church, when people in the southern United States still practiced slavery, outsiders generally saw the Mormons as abolitionists. In fact, when Joseph Smith ran for president of the United States in 1844, he did so on an abolitionist platform.

After Joseph Smith’s death, however, Brigham Young and some other leaders increasingly preached reasons why the Church shouldn’t allow African Americans to be ordained to the priesthood. No doubt the prevailing racist attitudes of 19th-century America influenced them. In 1852, Young announced that from then on, Church policy said that blacks didn’t have access to priesthood ordination or to the temple and that they weren’t allowed to serve as missionaries. Throughout the 19th century and continuing into the 20th, Church leaders offered two teachings as the basic justification for the ban:

Leaders sometimes suggested that black skin was a consequence for individuals who were less valiant as spirits in the premortal life (for more on premortality, see Chapter 2). In this view, some individuals sided more readily with the Savior in the War in Heaven, and their reward was white skin, but others took their time to join forces with Christ and got black skin as a result. One folk belief was that blacks stayed neutral in the War in Heaven, but several leaders taught that it was impossible to remain neutral.

Leaders sometimes suggested that black skin was a consequence for individuals who were less valiant as spirits in the premortal life (for more on premortality, see Chapter 2). In this view, some individuals sided more readily with the Savior in the War in Heaven, and their reward was white skin, but others took their time to join forces with Christ and got black skin as a result. One folk belief was that blacks stayed neutral in the War in Heaven, but several leaders taught that it was impossible to remain neutral.

Even more pointedly, Brigham and others taught that those of black African descent were cursed with the mark of Cain, which set them apart because these spirits didn’t qualify to receive the priesthood. Some felt that this consequence was because these spirits, during premortality, were somehow in cahoots with Cain, a wayward spirit who still qualified to come to earth and gain a body. But early Church leaders more commonly tied black skin to the curse of Cain in Genesis 4 of the Old Testament, saying that blackness was the direct result of Cain’s sin on earth. This teaching was ironic because it seems to contradict the basic Mormon insistence that each human being is responsible only for his or her own sin, and not for someone else’s transgression. (For more on that, see Chapter 2.)

Even more pointedly, Brigham and others taught that those of black African descent were cursed with the mark of Cain, which set them apart because these spirits didn’t qualify to receive the priesthood. Some felt that this consequence was because these spirits, during premortality, were somehow in cahoots with Cain, a wayward spirit who still qualified to come to earth and gain a body. But early Church leaders more commonly tied black skin to the curse of Cain in Genesis 4 of the Old Testament, saying that blackness was the direct result of Cain’s sin on earth. This teaching was ironic because it seems to contradict the basic Mormon insistence that each human being is responsible only for his or her own sin, and not for someone else’s transgression. (For more on that, see Chapter 2.)

The speculative belief about the mark of Cain, sadly enough, was popular in many other Christian traditions in the 19th century and into the 20th, but Mormonism had the unfortunate distinction of holding onto it longer than the Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians. The teaching on the premortal life was, of course, uniquely Mormon. Both ideas seem to have a basis in Mormon scripture (see Chapters 9 and 10), in which a curse of “blackness” is interpreted in a literal, physical way and not in a merely spiritual sense.

Changing Church policy

In June 1978, President Spencer W. Kimball announced that the priesthood was extended to all worthy men, regardless of race. Kimball’s revelation, contained in the Doctrine and Covenants as one of two official declarations near the end of the book, obviously came as a result of deep prayer and constant questioning of the Lord.

Some outsiders dismissed the revelation as politically convenient, the Church’s response to pressures from a wider culture that increasingly focused on civil rights. But if that were the case, the declaration probably would’ve happened a decade earlier. Instead, the catalyst seems to have been the Church’s international expansion into multiracial areas such as Brazil, where it was about to dedicate a temple that many local members could never enter under the previous policy.

For many members of all races, the ban on blacks holding the priesthood caused considerable heartache. As with Kennedy’s assassination, many Mormons can still tell you exactly where they were and what they were doing when they first heard the electrifying news that blacks could finally hold the priesthood. In Utah, drivers who heard the announcement on the radio turned on their car lights in the middle of the day and honked at one another, some weeping tears of gratitude and pulling over for spontaneous prayer.

Finding remnants of racism

Although the 1978 revelation was clear that all worthy males can hold the priesthood, it didn’t specifically denounce the folk beliefs that people had touted for decades as justification for the old priesthood ban. Because the Church has never come out and said that blacks could’ve been as valiant in the premortal life as other people or refuted the notion that they all carry the mark of Cain, some Mormons continue to hold onto these politically incorrect beliefs and assume that they apply across the board as doctrine.

These old folk beliefs still linger in some LDS literature, for instance. The current edition of Apostle Bruce R. McConkie’s influential work, Mormon Doctrine, still contains 1966 statements that the 1978 priesthood revelation surely overrode. In the book, for example, McConkie writes that those of African ancestry “have been cursed with a black skin, the mark of Cain, so they can be identified as a caste apart, a people with whom the other descendants of Adam should not intermarry.” The fact that this statement, which many Mormons regard as untrue and offensive, remains in a quasi-official book written by a General Authority and published by a Church-owned press is a problem for many Latter-day Saints, black and white. Despite McConkie’s statement, it’s not uncommon to find interracial marriage and adoption among today’s Latter-day Saints.

Mormon leaders hesitate to openly declare a past teaching to be wrong, preferring instead to quietly emphasize the Church’s new direction and focus on the positive. Earlier editions of McConkie’s book, for example, used to say that blacks “were less valiant in [the] pre-existence.” That statement has disappeared. McConkie himself disavowed his earlier teachings shortly after the 1978 revelation, urging members to forget everything he ever said on the issue and instead to honor the “new flood of intelligence and light on this particular subject.” And in 2004, a spokesman for the Public Affairs Department of the LDS Church stated, “Various opinions about the reason for this [priesthood] restriction were superseded by the 1978 revelation,” which is certainly helpful, although this statement doesn’t specify exactly which racial opinions are remnants of the past.

A prophet probably won’t come right out and say, “Brigham Young was wrong about race,” but he may do what LDS President Gordon B. Hinckley did in 1998 when speaking before a gathering of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. In his speech, President Hinckley affirmed the sacred worth and divine nature of every person, regardless of race. “Each of us is a child of God,” Hinckley declared. “It matters not the race. It matters not the slant of our eyes or the color of our skin. We are sons and daughters of the Almighty.”

Welcoming black Mormons today

Since the 1978 priesthood revelation, the LDS Church has experienced a miniexplosion of conversions in Africa, the Caribbean, and Brazil. (For more on this growth, see Chapter 14.) Most of these new converts are black or multiracial. Conversions among blacks in the United States have been slower, but they’ve still increased substantially since 1978. (The Church doesn’t keep statistics on members’ race and ethnicity, but anecdotal evidence and surveys suggest that black converts in the United States have a low retention rate, a possible indication that African American members’ initial enthusiasm for the gospel diminishes when they find out about Mormonism’s racially troubled history or don’t adjust well into white-dominated Mormon culture.)

Some black members have entered the ranks of local and regional leadership in the Church, serving as bishops and in stake positions (see Chapter 6). Three men of African descent have served as General Authorities (see Chapter 8) since 1978, a number that will surely increase as more blacks rise through the ranks of Church leadership.

Meanwhile, the LDS Church has made conscious efforts to reach out to the black community in various ways, such as the following:

A company owned by the Church publishes books on the experiences of black Mormon pioneers, raising the profile of African American Mormons.

A company owned by the Church publishes books on the experiences of black Mormon pioneers, raising the profile of African American Mormons.

The Church sponsors a semiofficial organization of black Latter-day Saints called the Genesis Group (www.ldsgenesisgroup.org), which helps black members find fellowship and common ground.

The Church sponsors a semiofficial organization of black Latter-day Saints called the Genesis Group (www.ldsgenesisgroup.org), which helps black members find fellowship and common ground.

Mormons have initiated programs to help African Americans of any faith research their genealogy.

Mormons have initiated programs to help African Americans of any faith research their genealogy.

In particular, in 2001 the Church released 11 years’ worth of research on the Freedman’s Bank, which in the 1870s held the financial records and family history information of thousands of former slaves. Approximately 10 million African Americans can now find out about their ancestors as far back as the 18th century. In 2004, the Church contributed time and money to creating a FamilySearch center in the new National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati, Ohio.

These efforts are small but promising bridges in the future relations of blacks and Mormons, who may find reconciliation by exploring the past.

Beyond Molly: Women in the LDS Church

She bakes delicious bread, wears corduroy jumpers, and shuttles her six kids around in a slightly battered minivan. She’s a stay-at-home mom who decorates her suburban home with quilts she made herself and serves as president of the Relief Society, the Church’s organization for women.

Meet Molly Mormon, who serves as most people’s stereotype for a Mormon woman. (She’s also the bogeywoman to Latter-day Saint women who feel they can’t measure up.) Is she an accurate stereotype? Yes and no. True, every ward has at least one Molly Mormon, and the stay-at-home mom remains the gold standard for Mormon families. Mormons are totally committed to the idea that children come first and believe that no role is more fulfilling than parenthood. A popular saying in the Church is that no success outside the home can ever compensate for failure within it. Because of this claim, Mormons place a high value on keeping a parent at home full time with the children. Usually, the mom gets that job, though we do know of a few LDS families with stay-at-home dads.

But the story has another side, too. Mormon women today take up public as well as private roles on a wide and diverse spectrum. Mormon women in the United States are statistically just as likely to work outside the home as non-LDS women, though they’re more likely to work part time and take off a chunk of time when their kids are young. Mormon women are in the workplace in all kinds of fields — education, medicine, law, science, business, what have you. Many resent the assumption that Mormon women are somehow oppressed.

Pointing out where Mormon theology serves women well

Mormon women often feel that their religion offers elements that are uniquely empowering to women, including

Belief in a Heavenly Mother: Mormonism may be unique among Christian denominations in its conviction that God has a dynamic and holy female partner (see Chapter 3). Although Mormons don’t yet know everything about Heavenly Mother because God hasn’t revealed much about her, they cherish the knowledge that they have a mother in heaven as well as a mother on earth.

Belief in a Heavenly Mother: Mormonism may be unique among Christian denominations in its conviction that God has a dynamic and holy female partner (see Chapter 3). Although Mormons don’t yet know everything about Heavenly Mother because God hasn’t revealed much about her, they cherish the knowledge that they have a mother in heaven as well as a mother on earth.

An unusually positive view of Eve and her role in creation: As we explain in Chapter 2, Mormons don’t see Eve as someone to blame for bringing sin into the world or — darn it! — forcing us all to forsake the good life in Eden. Instead, Eve was a heroine who understood that the highest and noblest task of humanity was to become more like God and that she could help open the way only by eating the forbidden fruit of mortality. You go, girl!

An unusually positive view of Eve and her role in creation: As we explain in Chapter 2, Mormons don’t see Eve as someone to blame for bringing sin into the world or — darn it! — forcing us all to forsake the good life in Eden. Instead, Eve was a heroine who understood that the highest and noblest task of humanity was to become more like God and that she could help open the way only by eating the forbidden fruit of mortality. You go, girl!

An understanding of the divine nature of each woman: In the Mormon view, it takes two to tango up into the celestial kingdom, and women are every bit as holy and innately divine as men. (In fact, some would argue that women are naturally more holy, but we’ll save that topic for another day.) For more info on the celestial kingdom and eternal marriage, see Chapters 2, 5, and 7.

An understanding of the divine nature of each woman: In the Mormon view, it takes two to tango up into the celestial kingdom, and women are every bit as holy and innately divine as men. (In fact, some would argue that women are naturally more holy, but we’ll save that topic for another day.) For more info on the celestial kingdom and eternal marriage, see Chapters 2, 5, and 7.

Is abortion ever okay?

The short Mormon answer to the question of whether abortion is justified is extremely rarely. Mormons don’t support abortion except in the following unusual circumstances:

When a physician believes the mother’s life is in serious danger

When a physician believes the mother’s life is in serious danger

In cases involving rape or incest

In cases involving rape or incest

When a physician has determined that the baby will have defects leading to death shortly after birth

When a physician has determined that the baby will have defects leading to death shortly after birth

Even in these circumstances, many Mormons would choose to have the baby, because LDS belief and practice are so geared toward the fundamental importance of children. For Mormons, remember, a mortal life is necessary for the progression of each spirit to the celestial kingdom. So abortion is a kind of double-whammy sin: Abortion violates the sixth commandment (“Thou shalt not kill”) by taking a physical life, and it also prevents — or at least delays — a person’s ability to progress spiritually.

When female converts join the LDS Church, they’re typically asked during the baptismal interview if they’ve ever had an abortion. Mormons consider unnecessary abortion to be such a serious sin that an individual must specifically repent of it before the sacred ordinance of baptism can be administered. The Church can discipline members who receive, perform, or agree to unnecessary abortions.

Drawing a line between women and the priesthood

Although Mormon women may seem to be second-class citizens because they don’t hold the priesthood, most Mormon women don’t feel that way. In the first place, the priesthood, like other spiritual gifts, is a vehicle for service. The role isn’t an opportunity for men to lord their position over women but to serve the Church and the world. (In fact, the first level of the Aaronic Priesthood is called deacon, which stems from the Greek word for servant.) Moreover, Mormon women can still receive all the blessings of the priesthood even though they aren’t ordained to it. (For more on the priesthood, see Chapter 4.)

Mormon women can hold a number of nonpriesthood callings, such as teachers, auxiliary presidents, counselors (see Chapter 6 for those three positions), family-history specialists, media-relations directors, and full-time missionaries (see Chapter 14). On a practical level, women generally have as much to do with the running of local church units as men do. In fact, most Mormon women feel they have all the opportunities for service that they can handle!

A few LDS women have fought for women to be granted the priesthood, and though President Gordon B. Hinckley hasn’t ruled out the idea as a future possibility, he and other Church leaders have expressed doubt about it. A number of folk rationales exist among rank-and-file Mormons for why women don’t hold the priesthood, though no official doctrine on this point exists. For some possible explanations, see Chapter 20.

Hullabaloo over History and Holy Books

Some of the Church’s most persistent controversies stem from ongoing debates about its history and sacred texts. In this section, we touch on some of these enduring arguments — er, discussions — with a special focus on the Book of Mormon and the LDS commitment to faithful history.

The Book of Mormon in the hot seat

Type Book of Mormon problems into any Internet search engine and you’ll get tens of thousands of hits. Bitter anti-Mormons spit out criticisms of the Book of Mormon, claiming that it doesn’t present real history and that the story is a big hoax. Meanwhile, zealous Latter-day Saints counter with what they say is evidence for the book’s historicity and trustworthiness, answering their critics’ charges and sometimes unfairly cutting down the critics themselves.

Questioning the Book of Mormon

Welcome to the Book of Mormon wars. If you thought the wars discussed in the Book of Mormon were fierce, wait till you get a taste of the ongoing wars about the book. The questions never end: Did Joseph Smith make it up? Did he plagiarize it from someone else? Can archaeological findings prove or disprove the Book of Mormon? Why haven’t archaeologists discovered the great cities that the book mentions? How come today’s Native Americans don’t have Hebrew DNA? And on and on. Although we can’t answer all these questions for you (about a gazillion more-detailed sources are available to help), see Table 15-1 for some of the more common criticisms of the Book of Mormon and the Mormon response.

| Issue in Question | The Mormon Response |

|---|---|

| How can the Book of Mormon talk | The word horse in the Book of Mormon |

| about horses, when no archaeological | may be only an approximate English |

| record of horses before the arrival of | translation, with a similar animal |

| Columbus exists? | intended in the original language. (This |

| theory is also true of the mentions of | |

| iron and steel in the Book of Mormon.) | |

| Of course, horses may have existed in | |

| ancient America, but physical evidence | |

| hasn’t yet sprung up. | |

| Didn’t Joseph Smith just make up a lot | Mormons don’t think so. At least |

| of biblical-sounding names to make the | 14 names in the Book of Mormon aren’t |

| Book of Mormon appear to be ancient? | found in the Bible but have been discov |

| ered on various Hebrew inscriptions and | |

| funeral documents from the period. | |

| Because archaeologists have discov | |

| ered these names since the 1960s, | |

| Joseph Smith couldn’t have known that | |

| they were authentic Hebrew names. | |

| Doesn’t the fact that Christ says | The texts have some minor differences, |

| almost exactly the same thing when | but they’re indeed very similar. From the |

| he appears in the Book of Mormon as | Mormon point of view, this fact doesn’t |

| he does in the New Testament show | present a problem. Why would Christ |

| that Joseph Smith merely plagiarized | teach one gospel to the people in the |

| New Testament passages? | Old World and a totally different one to |

| the folks in the New World? | |

| Isn’t the Book of Mormon too unsophis- | True, the translation sometimes sounds |

| ticated in its writing style to be an | clunky in English (“and it came to pass,” |

| authentic work of scripture? | repeated ad nauseam). But the Book of |

| Mormon also features sophisticated | |

| allegories, chiasmus (complex, symmet | |

| rical literary patterns), and some beauti | |

| ful poetry. |

Putting up a defense

In 1979, some ambitious Mormons founded an organization called the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, or FARMS for short, to expand Book of Mormon scholarship and prove to the world that the Book of Mormon is legit. (And no, its scholars don’t come to work in overalls and straw hats.)

FARMS is unapologetically apologetic, by which we mean that the organization exists to defend the faith. In fact, FARMS is now housed at Brigham Young University, having taken its place as a sort of officially unofficial Mormon organization. The Church doesn’t directly sponsor the organization, but leaders have certainly used some FARMS findings in official writings and settings.

FARMS has raised the bar for Mormon scholarship, professionalizing it to the extent that it has answered many of the old anti-Mormon criticisms with serious research into linguistics, archaeology, biblical studies, and the like.

Conquering questions about genetics

The hot new issue these days in the Book of Mormon wars is definitely the problem of DNA studies. In a nutshell, DNA tests have shown no genetic link between modern-day Native Americans and Jews, or descendants of the original Israelites. If Native Americans are supposed to be descended from the Lamanites of the Book of Mormon (see Chapter 9), wouldn’t these two groups have a direct genetic link?

Not necessarily. For starters, Mormon scholars today are very careful to note that not all Native Americans are necessarily descended from the Lamanites; in fact, given the amount of murder at the end of Book of Mormon times, it’s likely that very few are. Although some 19th-century Mormons boldly claimed Lamanite ancestry for all American Indian peoples, Mormons today realize that the reality is probably far more complex. The Book of Mormon itself never says that all Native Americans are Lamanite descendants or that Nephites and Lamanites were the only people in the New World from 600 B.C. to A.D. 400, the 1,000-year period when Book of Mormon events took place. (In fact, the book is pretty clear that other groups were there already.) In addition, a DNA researcher at Brigham Young University has made a convincing case that although DNA studies can establish some genetic relationships, they can’t prove lack of genetic relation so far back.

The DNA findings, then, don’t disprove the Book of Mormon, though they may disprove former interpretations of the Book of Mormon.

Faithful versus accurate history

One of the other ongoing hot-button issues for Mormons is the question of how to appropriately communicate Mormon history. Some Latter-day Saints prefer to write history by highlighting how God intervened at key moments to guide his people, the Mormons, to ever-greater righteousness. Sometimes, this method risks leaving out evidence of the flaws and foibles of the human participants in history. Others write Mormon history in the same way that they’d tell the story of any group, focusing on human activity and presenting key leaders such as Joseph Smith with warts and all. Some Church leaders feel that this method inappropriately downplays the miraculous and may cause members to lose faith in the ways God acted through LDS leaders of the past.

Obviously, these two approaches can sometimes come into conflict. Such was the case in September 1993, when six members of the LDS Church were excommunicated or disfellowshiped (a lesser disciplinary action after which an individual remains a member of the Church but can’t take the sacrament, hold a calling, or enter the temple). All six had published or spoken publicly about Mormon history, theology, or leadership; several were outspoken feminists.

At the end of the 20th century and into the 21st, the debates became quieter, with few high-profile excommunications. Perhaps because of the negative media scrutiny in 1993, or perhaps because of the gentle patience that has marked Gordon B. Hinckley’s presidency (he became the prophet in 1995), the Church seems to have backed off slightly from public battles. Some signs suggest that the Church may be relaxing its opposition to secular approaches to history. Regarding the Mountain Meadows Massacre controversy, for example (see Chapter 13), the Church has agreed to open its archives to investigators and make available every document it possesses related to that tragedy.

Evolution or evil-ution?

Some Mormons view evolution as one of God’s creative tools, but others deny it happens or say it’s merely the byproduct of a fallen world.

Mormons don’t profess to understand exactly how, when, or where God created humans or what went down prior to Adam, but most Mormon leaders teach that God’s actual spiritual children have been inhabiting human bodies on this planet for only about 6,000 years. In any event, nothing in Mormon theology precludes the notion that other biological forms existed on earth millions of years ago, especially since some Mormons believe that the “days” referred to in the Genesis creation story symbolize a much longer period of time that could be consistent with the time span of organic evolution. Mormons expect God to reveal the solution to the fossil puzzle—dinosaurs, Neanderthals, and so on—in his own due time. In the meantime, Mormon biologists take comfort in the belief that scientific truth and religious truth spring from the same basic source, with a great deal still to learn in both arenas.

Various leaders of the Church have agreed or disagreed with evolutionary theory, but the Church has never taken a specific official position on the subject. Back in 1909, when evolution was a hotter topic, the LDS First Presidency affirmed that

God created humans in his own image.

God created humans in his own image.

Adam was the first human on this earth.

Adam was the first human on this earth.

Human bodies bear the characteristics of the eternal spirits dwelling within.

Human bodies bear the characteristics of the eternal spirits dwelling within.

Humans didn’t develop from “lower orders of the animal creation” but resulted from a “fall” from a higher state of being.

Humans didn’t develop from “lower orders of the animal creation” but resulted from a “fall” from a higher state of being.

According to this First Presidency statement, the only form of human evolution that really matters to Mormons is that everyone is capable of eventually evolving into a god.

Today, LDS Church–owned Brigham Young University teaches the theory of evolution, along with other scientific theories that may or may not stand the test of time.

Voices in Conflict

Inside Mormonism, freewheeling debate about all aspects of the religion bubbles up in a variety of independent venues, despite official attempts to keep matters sweet and simple. From outside the faith, people who are convinced that Mormonism isn’t true, as well as ex-Mormons who are disgusted with the faith, broadcast their exposés and warnings to anyone who will listen.

Free speech on the inside

For racehorses, blinders serve a valuable purpose by keeping the horse focused on reaching the finish line. Under mandate to bring people to the Savior and prepare for his Second Coming, Mormonism uses some focusing techniques to keep people aimed at the goal. The main formal focusing technique used by the Church as an institution is the Correlation Committee, which simplifies and sanitizes all official Mormon messages to members and the world.

However, for many Mormons — especially those with an intellectual or artistic bent — there’s a time and place for taking off the blinders and looking at situations from a personal, realistic slant, as opposed to just taking the Church’s position at face value. The Internet, for example, is full of Mormons having frank, intimate, questioning conversations that the Correlation Committee would never approve for official Church communication channels.

When it comes to formalized publications and meetings, two independent organizations carry the torch of open Mormon expression:

The Dialogue Foundation, which publishes Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought

The Dialogue Foundation, which publishes Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought

The Sunstone Education Foundation, which publishes Sunstone magazine and holds symposia

The Sunstone Education Foundation, which publishes Sunstone magazine and holds symposia

Both groups provide essential outlets for freethinking Mormons, although both struggle with sometimes coming across as too critically authoritative and with not paying enough respectful attention to traditional, orthodox views.

Sunstone

More calm and careful now than it used to be, the Sunstone Education Foundation (www.sunstoneonline.com) explores Mormon topics in two ways: by publishing a magazine and by sponsoring yearly symposia in Salt Lake City and other cities across the country. Following the motto “Faith Seeking Understanding,” this group bills itself as an open, honest, and respectful forum for examining and expressing all aspects of Mormonism.

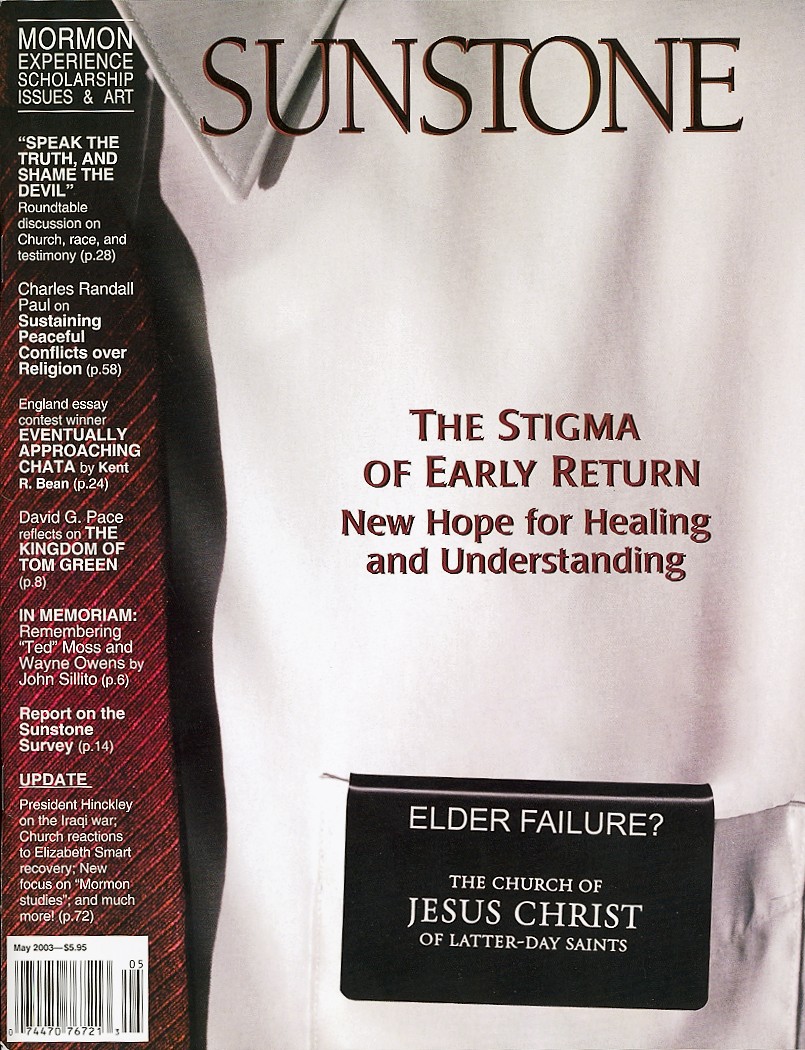

Sunstone magazine (shown in Figure 15-1), which ideally comes out six times a year, is a lively, visually appealing, 80-page smorgasbord of Mormon analysis and art, mixing heavy-duty articles with lighter reading, including cartoons and Mormon news.

Held in Salt Lake City and in smaller versions around the United States, Sunstone symposia strive for overall balance, although the more-controversial sessions tend to get blown out of proportion when the media covers them. Active, faithful Mormons publish articles in the magazine and speak in Sunstone forums, and so do inactive Mormons, excommunicants, outside observers from other faiths (or no faith), and representatives of fringe groups.

|

Figure 15-1: A typical edition of Sunstone magazine. |

|

Cover image courtesy of Sunstone magazine.

Here’s a sampling of session titles from the 2004 Sunstone symposium:

“Internet Mormons versus Chapel Mormons”

“Internet Mormons versus Chapel Mormons”

“Real Goddesses Have Curves (and Identities)”

“Real Goddesses Have Curves (and Identities)”

“The Best Idea in Mormonism”

“The Best Idea in Mormonism”

“How ‘Christian’ Should Mormonism Strive to Be?”

“How ‘Christian’ Should Mormonism Strive to Be?”

Dialogue

The main activity of the Dialogue Foundation (www.dialoguejournal.com) is publishing a quarterly journal that aims to connect Mormonism with the bigger picture of world religious thought and human experience. Published in a format somewhat like that of a loosely refereed academic periodical (with scant illustrations and occasional scholarly articles that seem to go on forever), Dialogue includes many provocative and groundbreaking articles, poems, short stories, and works of visual art.

Criticism from the outside

From the beginnings of Mormonism, perhaps no other U.S. religion has inspired such a large industry of critics — and yes, we mean industry, because some people earn their livelihoods from anti-Mormonism. This resistance isn’t surprising, considering that the LDS Church claims to be the world’s only true religion and aggressively evangelizes members of other faiths. From the Mormon perspective, the devil is the one who’s inspiring people to attack and misrepresent God’s church.

Sign-wielding anti-Mormon protestors routinely picket large Mormon events, and countless books, pamphlets, Web sites, and films attempt to expose the LDS Church as a sham. Nearly all anti-Mormons hail from evangelical Protestant Christianity, particularly the Southern Baptist denomination. In fact, many of the most dedicated anti-Mormons are former Mormons who “found Christ.” Their purpose is twofold: helping people leave Mormonism and keeping members of their own flocks from converting to Mormonism.

What’s the beef?

Common anti-Mormon complaints include the following:

The Bible: Much of the Protestant objection to Mormonism arises from different interpretations of Bible teachings, particularly the Godhead’s nature and identity, how and why people are saved, and what happened to the Savior’s church after he left the earth. In addition, conservative Protestants object to Mormonism’s acceptance of scripture beyond the Bible. (For more on Mormon views regarding the Bible, see Chapter 9.)

The Bible: Much of the Protestant objection to Mormonism arises from different interpretations of Bible teachings, particularly the Godhead’s nature and identity, how and why people are saved, and what happened to the Savior’s church after he left the earth. In addition, conservative Protestants object to Mormonism’s acceptance of scripture beyond the Bible. (For more on Mormon views regarding the Bible, see Chapter 9.)

The Book of Mormon: As we discuss earlier in this chapter, critics find many problems with Mormonism’s key scripture, mostly along the lines of alleged chronological errors and lack of scientific proof. (For more on the Book of Mormon, see Chapter 9.)

The Book of Mormon: As we discuss earlier in this chapter, critics find many problems with Mormonism’s key scripture, mostly along the lines of alleged chronological errors and lack of scientific proof. (For more on the Book of Mormon, see Chapter 9.)

Brigham Young: Joseph Smith’s prophetic successor made several statements that haven’t aged well, including racist teachings and the concept that Adam was in fact God, which today’s Church doesn’t accept as doctrine. (For more on Brigham Young, see Chapters 12 and 13.)

Brigham Young: Joseph Smith’s prophetic successor made several statements that haven’t aged well, including racist teachings and the concept that Adam was in fact God, which today’s Church doesn’t accept as doctrine. (For more on Brigham Young, see Chapters 12 and 13.)

Cult: In sociological lingo, a cult is a small and intense religious group that unites around a single charismatic individual. Some Mormons acknowledge that their faith began as a cult of Christianity, in much the same way that Christianity began as a cult of Judaism. However, the term has taken on extremely negative connotations, and many anti-Mormons claim that Mormonism is still a cult, even 175 years and 12 million members later. (For more on Mormonism’s founding, see Chapter 4.)

Cult: In sociological lingo, a cult is a small and intense religious group that unites around a single charismatic individual. Some Mormons acknowledge that their faith began as a cult of Christianity, in much the same way that Christianity began as a cult of Judaism. However, the term has taken on extremely negative connotations, and many anti-Mormons claim that Mormonism is still a cult, even 175 years and 12 million members later. (For more on Mormonism’s founding, see Chapter 4.)

Joseph Smith: The Angel Moroni told Mormonism’s founding prophet that his name would “be both good and evil spoken of among all people” (Joseph Smith — History 1:33 in the Pearl of Great Price; see Chapter 10). Some of the most vicious anti-Mormon attacks focus on Joseph’s own alleged character flaws, such as his youthful treasure digging and adult practice of polygamy. (For more on Joseph, see Chapters 4, 9, 10, and 11.)

Joseph Smith: The Angel Moroni told Mormonism’s founding prophet that his name would “be both good and evil spoken of among all people” (Joseph Smith — History 1:33 in the Pearl of Great Price; see Chapter 10). Some of the most vicious anti-Mormon attacks focus on Joseph’s own alleged character flaws, such as his youthful treasure digging and adult practice of polygamy. (For more on Joseph, see Chapters 4, 9, 10, and 11.)

Masonry: Much has been made about the similarities between Mormon temple rites and Masonic rituals. (For more on Mormon temples, see Chapter 7.)

Masonry: Much has been made about the similarities between Mormon temple rites and Masonic rituals. (For more on Mormon temples, see Chapter 7.)

The Mormon response

As with most controversies in the religious arena, countering or proving anti-Mormon claims with hard evidence that either side would accept is difficult. Some Mormons enjoy debating, but most simply express their hope that truth seekers will learn about the religion from fair, trustworthy sources; take their questions and concerns directly to God in prayer; and then follow their own hearts.

Mormons sometimes warn each other to shun faith-destroying anti-Mormon literature, because it’s not unheard of for members to abandon the faith due to doubts raised by anti-Mormons. The LDS Church itself doesn’t typically respond directly to anti-Mormon claims, but some groups make an effort to defend the faith, most notably the Brigham Young University–based FARMS (farms.byu.edu), which we discuss earlier in this chapter, and the independent Foundation for Apologetic Information & Research (www.fairlds.com).

Getting along with other religions

Brigham Young famously urged tolerance and the right of all people to worship as they see fit. He told the Mormons to leave their neighbors alone and “let them worship the sun, moon, a white dog, or anything else they please, being mindful that every knee has got to bow and every tongue confess.” So although Mormons believe that in the afterlife all people will acknowledge Jesus Christ as Lord, in this world we all have to get along despite our religious differences.

How does that idea play out in daily life? Mormons believe very strongly in not allowing any one religion to be fused with civic government and in permitting all people to worship or not worship as they please. (See D&C 134 and the 11th Article of Faith.) Mormons do, of course, try to persuade governments to pass legislation that they view as moral and just — however, they feel the government doesn’t have the right to sponsor or suppress anyone’s religion.

Although they believe that their church is the only institution that Christ established on the earth, Mormons applaud the many righteous works of members of other denominations who are inspired by the Savior’s love and example. President Gordon B. Hinckley, the LDS prophet at this writing, speaks often and very positively about the strong friendships he enjoys with individuals of other faiths and the good that he believes they’re achieving in the world. Most Mormons — especially those who live outside of the U.S. Intermountain West and are therefore part of a minority religion — value the moral contributions of their non-Mormon neighbors, though they may agree to disagree about points of theology. In addition, the LDS Church sometimes donates money to other religions, such as in 2000 when it gave a Hindu society in Utah $25,000 to help build a Hindu temple there.

Beyond Heterosexual Monogamy

In Mormonism, the two most troublesome forms of sexuality usually overlap with opposite ends of the ideological spectrum. Polygamists tend to be conservative fundamentalists who claim that they’re upholding true Mormon tradition and that the mainstream LDS Church has drifted astray. Practicing Mormon homosexuals, on the other hand, tend to be progressive liberals who celebrate change and hope the LDS Church will one day grow to accept them.

Ultimately, however, the LDS Church excommunicates people who persist in either taboo sexual behavior. Meanwhile, many members struggle to resist homosexual desires or come to terms with their polygamous heritage.

Born that way?

For Mormons, heterosexual procreation is a basic principle of the universe and an essential element of God’s nature. In addition, the LDS Church’s recent Proclamation on the Family (see Chapter 10) declares that gender is an eternal attribute of each person’s soul. When it comes to homosexual tendencies and gender ambiguities, Mormons see those challenges as symptoms of an imperfect, fallen world that the Savior will eventually heal.

In the meantime, the LDS Church says that homosexual behavior is a sinful moral choice rather than an acceptable lifestyle option or unavoidable part of someone’s personality. However, most Mormons recognize that some people — for complex reasons probably related to both temperament and environment — truly struggle with unwanted homosexual impulses. In the Mormon view, involuntarily feeling homosexual attraction isn’t sinful; acting on the temptation — or failing to resist it — is where the sin comes in. In addition, Mormon authorities frequently affirm that people must treat homosexuals with kindness and charity — in other words, “Hate the sin, but love the sinner,” as it’s commonly said.

Mormons don’t like to use the word gay because it implies acceptance of the gay cultural identity. Instead, Latter-day Saint authorities use terms such as same-gender attraction, which describes the temptation rather than the person. Although Mormons believe that God doesn’t allow people to be tempted beyond what they can bear, they understand that some battles may last an entire lifetime, with victory only gradually emerging after years of effort and resistance.

Overcoming the sin

In bygone times, Mormons were among those who tried to cure homosexuality via extreme measures, such as aversion therapy, shock treatments, and — perhaps most ill-advisedly of all — heterosexual marriage. Nowadays, however, Mormons struggling with same-gender attraction can usually get enlightened assistance from LDS-affiliated therapists. In general, these therapists help their clients reclaim what the Church teaches is their God-given heterosexuality. They try to help patients figure out where their gender development went off-kilter so that those people can rebuild a proper sexual identity. Some Mormons eventually overcome same-gender attraction enough to become successful heterosexuals, and some never do.

Several support groups are available for Mormons dealing with same-gender attraction, whether their own or that of a loved one. An independent group called Evergreen International (www.evergreeninternational.org) finds the most favor among mainstream Mormons, with LDS General Authorities often speaking at its conferences. Evergreen’s mission is to help individuals “overcome homosexual behavior and diminish same-sex attraction.”

However, some people remain in the Church while defining themselves as gay. In general, the LDS Church doesn’t discipline its members for having a homosexual orientation, only for acting upon it by engaging in any form of nonmarital sex. A few organizations and support groups cater to homosexual Latter-day Saints, including Affirmation (www.affirmation.org), which seeks to help gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender Mormons come to terms with their identities.

Fighting gay marriage

Although Mormon authorities warn against any abuse or mistreatment of people with a homosexual orientation, the LDS Church formally opposes gay marriage. In fact, it has donated funds to support anti-gay-marriage campaigns and urges members to exercise their political muscle against it. Not since the LDS Church helped defeat the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1970s has the official organization spoken out so prominently on a national social issue — and the fight’s only just beginning.

I do, I do, and I do again . . .

Ah, the P-word that just won’t go away: polygamy. If there’s one thing that most Mormons — especially missionaries and public relations workers — wish they could change about the religion’s image, it may be the 19th-century practice of polygamy. Although the mainstream LDS Church completely abandoned the earthly practice of polygamy by the early 20th century, Mormon-style polygamy is still going strong among rebel sects in Utah and elsewhere, to the mainstream Church’s chagrin. (For more on Mormon polygamy’s historical roots and rationales, see Chapter 13.)

Nowadays, the way most Mormons feel about contemporary polygamists is similar to how many Protestant Christians feel about Mormons. Not only does the LDS Church excommunicate polygamists, but also Church officials insist that polygamists shouldn’t be called Mormons or linked in any way with the LDS Church. On the other hand, polygamists claim they’re the only true Mormons, because they’ve stayed true to founding prophet Joseph Smith’s teachings instead of allowing themselves to become corrupted by the pressures of the world.

For those who don’t care much about religious issues, Mormon polygamists still hold considerable fascination, as if the Amish had adopted free love. Increasingly, Mormon-related polygamists pop up in the national news, often for crimes such as child or spousal abuse, incest, statutory rape, child abandonment, welfare fraud, kidnapping, and murder. (Mainstream Mormons point to these crimes as evidence that polygamy without God’s sanction is corrupt.) In addition, polygamists are starting to crop up more often in popular culture. In 2004, for example, cable giant HBO announced that it’s developing — with the help of producer Tom Hanks — a new drama called Big Love about a polygamous family living in Utah.

Although many grassroots Mormons appreciate the Church’s refusal to talk about its polygamous past, others wish the Church could find a way to more openly and positively come to terms with its history. After all, many born-and-bred Mormons have polygamous ancestors, and LDS scriptures still proclaim doctrines of plural marriage (most notably section 132 of the Doctrine and Covenants). Even today, many mainstream Mormons believe — or perhaps fear is a better word — that some people will practice polygamy in heaven. In fact, in today’s LDS temples men can still get eternally sealed to more than one woman, usually in the case of remarriage after the first wife dies (see Chapter 7).

The LDS Church and politics

The LDS Church has gotten involved in some key political efforts to defeat same-sex marriage legislation in states such as Alaska, Hawaii, and California, pouring money into the fight to prevent gay marriage from being recognized by the government. However, that departure is unusual for the Church, which typically shies away from direct involvement in politics. The Church makes exceptions to its general rule of nonintervention when issues arise that the First Presidency sees as a moral threat to the nuclear family, such as same-sex marriage or, in the 1970s, the Equal Rights Amendment.

That’s not to say that individual Mormons aren’t involved in politics. Latter-day Saints consider voting a religious imperative, and they’re active in all aspects of the political process. Utah remained pretty Democratic through the Great Depression, even going against the suggestion of the Church president (published on the front page of the Church-owned Deseret News) to vote against Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932. But after World War II a seismic political shift occurred, in which most of the Latter-day Saints followed their leaders, almost all of whom were at least leaning toward the Republican Party. This shift was due, at least in some measure, to the connection of LDS leader Ezra Taft Benson serving during President Eisenhower’s oh-so-Republican cabinet as secretary of agriculture in the 1950s. At that time, Mormons gravitated to the Republican Party because it strongly opposed communism, which many Mormons considered to be a serious threat.

Although the communist menace is a thing of the past, many U.S. Mormons still self-identify with the Republican Party today, especially because it seems to most closely embrace their conservative social stance. However, a vocal minority of Mormon Democrats is ever present, including the highly visible Nevada politician Harry Reid, who became the U.S. Senate Minority Leader in November 2004.

On a regular basis, the First Presidency issues an official statement that local leaders read from the pulpit of every LDS congregation around the world, reiterating the Church’s policy of neutrality when it comes to political parties, platforms, and candidates and encouraging individual members to study the issues and exercise their right to vote.