Chapter 1

Filing Information with the Streams Library

IN THIS CHAPTER

Seeing the need for a streams library

Seeing the need for a streams library

Opening a file

Opening a file

Dealing with errors

Dealing with errors

Working with flags to customize your file opening

Working with flags to customize your file opening

You’ve heard of rivers, lakes, and streams, and it’s interesting just how many common words are used in computer programming. That’s handy, because it lets programmers use words they already know with similar meaning. Using common terms makes it easier to visualize abstract concepts in a concrete way.

Most programmers think of a stream as a file — the type stored on a hard drive, Universal Serial Bus (USB) flash drive, or Secure Digital (SD) card. But streams go beyond just files. A stream is any type of data structure that you can access as a flow of data, essentially a sequence of bytes. Streams are used to access all sorts of devices, such as smart speakers. Rather than just fill a 500MB data structure and then drop it onto the hard drive, you write your data piece after piece; the information goes into the file.

Streams go further than a wide variety of devices, however. Opening an Internet connection and putting data on a remote computer usually requires a stream-based data structure. You write the data in sequence, one byte after another, as the data goes over the Internet like a stream of water, reaching the remote computer. The data you write first gets there first, followed by the next set of data you write, and so on.

This chapter discusses different kinds of streams available to you, the C++ programmer. In addition, you discover how to handle errors and use flags to modify how you open files.

Seeing a Need for Streams

When you write an application that deals with files, you must use a specific order:

-

Open the file.

Before you can use a file, you must open it. In doing so, you specify a filename.

-

Access the file.

After you open a file, you either store data into it (this is called writing data to the file) or get data out of it (this is called reading data from the file).

-

Close the file.

After you have finished reading from and writing to a file, you must close the file.

For example, an application that tracks your stocks and writes your portfolio to a file at the end of the day might do these steps:

- Ask the user for a name of a file.

- Open the file.

- For each stock object, write the stock data to the file.

- Close the file.

The next morning, when the application starts, it might want to read the information back in. Here’s what it might do:

- Ask the user for the name of the file.

- Open the file.

- While there’s more data in the file, create a new Stock object.

- Read an individual stock entry from the file.

- Put the data into the Stock object.

- Close the file.

- Other applications might be waiting to use the file. Some operating systems allow an application to lock a file, meaning that no other applications can open the file while the application that locked the file is using it. In such situations, another application can use the file after you close it, but not until then.

- When you write to a file, the operating system decides whether to immediately write the information onto the hard drive or flash drive/SD card or to hold on to it and gather more information, finally writing it all as a single batch. When you close a file, the operating system puts all your remaining data into the file. This is called flushing the file.

You have two ways to write to a file:

- Sequential access: In sequential access, you write to a file or read from a file from beginning to end. With this approach, when you open the file, you normally specify whether you plan to read from or write to the file, but not both at the same time. After you open the file, if you’re writing to the file, the data you write gets added continually to the end of the file. Or if you’re reading from the file, you read the data at the beginning, and then you read the data that follows, and so on, up to the end.

- Random access: With random access, you can read and write to any byte in a file, regardless of which byte you previously read or wrote. In other words, you can skip around. You can read some bytes and then move to another portion of the file and write some bytes, and then move elsewhere and write some more.

Back in the days of the C programming language, several library functions let you work with files. However, they stunk. They were cumbersome and made life difficult. So, when C++ came along, people quickly created a set of classes that made life with files much easier. These people used the stream metaphor we’ve been raving about. In the sections that follow, you discover how to open files, write to them, read from them, and close them.

Programming with the Streams Library

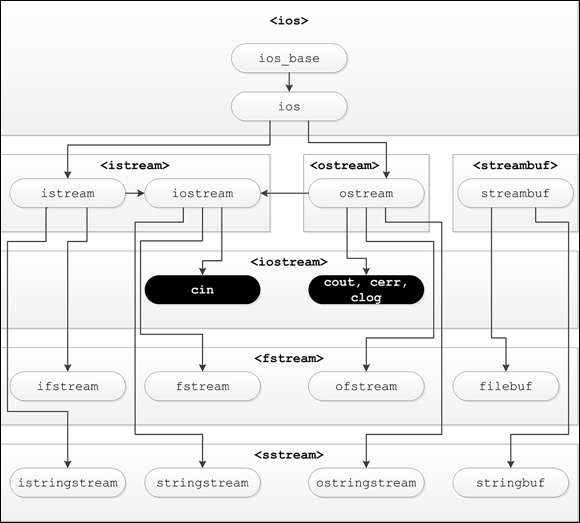

The libraries you use to work with streams are divided into various groups, each of which requires its own header. The libraries divide input and output into separate classes, as shown in Figure 1-1. In addition, the kind of input and output determines which header you use. The libraries also support specific commands that include cin and cout — the commands you have used for so many purposes so far.

FIGURE 1-1: Working with streams requires use of the appropriate headers and commands.

Now that you have a basic overview of how these various headers and commands work with the streams library to provide stream output, it’s time to get the details. The following sections help you understand how to use code to create streams of data that could go to a file, Internet connection, or some other location, such as a smart speaker.

Getting the right header file

The streams library includes several classes that make your life much easier. It also has several classes that can make your life more complicated, mainly auxiliary classes that you rarely use. Here are three of the more common classes that you use:

ifstream: This is a stream you instantiate if you want to read from a file. The if part of the name stands for input file.ofstream: This is a stream you instantiate if you want to write to a file. The of part of the name stands for output file.fstream: This is a stream you instantiate if you want to both read and write to a file. The f part of the name stands for file (in a general sense, rather than specifically for input or output).

Before you can use the ifstream, ofstream, or fstream classes, you #include <fstream>. As with many C++ classes and objects, you find these classes inside the std namespace. Thus, when you want to use an item from the streams library, you must either

- Prepend its name with

std, as in this example:std::ofstream outfile("MyFile.txt"); - Include a

usingdirective before the lines where you use the stream classes, as in this example:using namespace std;

ofstream outfile("MyFile.txt");

Opening a file

Opening a file means to obtain access to a file on disk. The process of opening a file returns a variable that allows you to do things with that file, such as read or write it. You have two options for opening a file:

- Create a new file: The file doesn’t currently exist, so you must create a new one.

- Open an existing file: The file does exist, so you open the existing one on disk.

Some operating systems treat these two methods as a single entity. The reason is that when you create a new file, normally you want to immediately start using it, which means that you want to create a new file and then open it. So the process of creating a file is often embedded right into the process of opening a file.

When you open an existing file that you want to write to, you have several choices:

- Erase the current contents; then write to the file.

- Keep the existing contents:

- Write your information to the end of the file. This is called appending information to a file.

- Write your information to the beginning of the file. This is called prepending information to a file.

- Search for a particular location in the file and then add data at that point.

- Overwrite all or part of the existing contents by replacing existing information with new information.

The FileOutput01 example code, in Listing 1-1, shows you how to open a brand-new file, write some information to it, and then close it. (But wait, there’s more: This version works whether you have the newer ANSI-compliant compilers or the older ones!)

LISTING 1-1: Using Code That Opens a File and Writes to It

#include <iostream>

#include <fstream>

using namespace std;

int main() {

ofstream outfile("../MyFile.txt");

outfile << "Hi" << endl;

outfile.close();

cout << "File Written!" << endl;

return 0;

}

The short application in Listing 1-1 opens a file called MyFile.txt. (The ../ part of the file path places the file in the parent directory for the example, which is the Chapter01 folder; see the “Finding your files” sidebar, in this chapter, for details.) The application opens the MyFile.txt file by creating a new instance of ofstream, which is a class for writing to a file. The next line of code writes the string "Hi" to the file. It uses the insertion operator, <<, just as cout does. In fact, ofstream is derived from the same class as cout, as shown in Figure 1-1, so anything you can do with cout you can also do with your file. When you finish writing to the file, you close it by calling the close() method.

If you want to open an existing file and append to it, you can modify Listing 1-1 slightly. All you do is change the arguments passed to the constructor, as follows:

ofstream outfile("MyFile.txt", ios_base::app);

The ios::app item is an enumeration inside a class called ios, and the ios_base::app item is an enumeration in the class called ios_base. The ios class is the base class from which the ofstream class is derived. The ios class also serves as a base class for ifstream, which is for reading files.

Reading from a file

You can read from an existing file. You perform this task in a manner similar to using the cin object to read from the keyboard. The FileRead01 example, shown in Listing 1-2, opens the file created by Listing 1-1 and reads the string back in. This example uses the parent directory again as a common place to create, update, and read files.

LISTING 1-2: Using Code to Open a File and Read from It

#include <iostream>

#include <fstream>

using namespace std;

int main() {

string word;

ifstream infile("../MyFile.txt");

infile >> word;

cout << word << endl;

infile.close();

return 0;

}

When you run this application, the string written earlier to the file in Listing 1-1 — Hi — appears onscreen.

Reading and writing a file

You may notice in Figure 1-1 that there is an fstream class that derives from iostream, which itself derives from both istream and ostream. Using the fstream class can save a lot of effort when you need to both read and write a file. The FileReadWrite01 example, shown in Listing 1-3, demonstrates how to both read and write the same file without closing the file handle first.

LISTING 1-3: Reading and Writing a File Using a Single Handle

#include <iostream>

#include <fstream>

using namespace std;

int main() {

fstream outfile("../MyFile.txt",

ios::in | ios::out | ios::trunc);

outfile << "Hi" << endl;

outfile.flush();

string Data;

outfile.seekg(0, ios::beg);

outfile >> Data;

outfile.close();

cout << "File Written!" << endl;

cout << Data << endl;

return 0;

}

The first part of this example works just like the example in Listing 1-1. You add opening modes to ensure that the handle works as anticipated: ios::in means that the file is open for input, ios::out means that the file is open for output, and ios::trunc means that the file is truncated (the old data is removed) before you add new data. Instead of closing the file, you call flush(), which ensures that the data actually appears on disk.

The example then creates an input string, Data, to receive information from the file. Before you can look at the file data, however, you must reposition the file pointer to point to the beginning of the file by using seekg(). A file pointer tells you the place where you will either read or write in a file. When you initially write to the file, the file pointer is at the end of the file, so to read the file you must reposition it to the beginning of the file. Notice that you now read the data just as you did in Listing 1-2.

Working with containers

You’re not very likely to write single bits of data to a file in most cases. You usually want to work with something more complicated, like a container (Book 5, Chapter 6 tells you about various kinds of containers). The basic idea is to combine the file techniques in this chapter with the container techniques shown in Book 5, Chapter 6 to create an application that works with containers. Listing 1-4 shows the OutputVector example that demonstrates how to perform this task.

LISTING 1-4: Saving a Vector to Disk

#include <iostream>

#include <fstream>

#include <vector>

using namespace std;

int main() {

vector<string> MyData;

MyData.push_back("One");

MyData.push_back("Two");

ofstream outfile("../MyData.txt");

for (Element : MyData)

outfile << Element << endl;

outfile.close();

cout << "File Written!" << endl;

return 0;

}

The example begins by creating a vector, MyData, that stores two strings. It then opens a file for output and uses a for loop to process the MyData elements one at a time. Each element appears on a separate line, which allows you to read the input file one line at a time to recreate the original vector from the disk file.

Handling Errors When Opening a File

When you open a file, all kinds of things can go wrong. A file lives on a physical device — a fixed disk, for example, or perhaps a flash drive or SD card — and you can run into problems when working with physical devices. For example:

- Part of the disk might be damaged, causing an existing file to become corrupted.

- You might run out of disk space.

- The directory doesn’t exist.

- Your application doesn’t have the right permissions to create a file.

- Removable media is missing.

- Network connection is down.

- File is locked.

- The filename was invalid — that is, it contained characters that the operating system doesn’t allow in a filename, such as

*or?.

- The operating system will generate an error (the default for Windows).

- The operating system will create the required path and file.

If you want to determine whether the ostream class was unable to create a file, you can call its fail() method. This method returns true if the object couldn’t create the file. That’s what happens when a directory doesn’t exist. The DirectoryCheck01 example, shown in Listing 1-5, demonstrates an example of using the fail() method.

LISTING 1-5: Returning True When ostream Cannot Create a File

#include <iostream>

#include <fstream>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

ofstream outfile("/abc/def/ghi/MyFile.txt");

if (outfile.fail()) {

cout << "Couldn't open the file!" << endl;

return 0;

}

outfile << "Hi" << endl;

outfile.close();

return 0;

}

When you run this code, you should see the message Couldn’t open the file! when your particular operating system doesn’t create a directory. If it does, your computer will open the file and write Hi to it.

As an alternative to calling the fail() method, you can use an operator available in various stream classes. This is !, fondly referred to as the bang operator, and you would use it in place of calling fail(), as in this code:

if (!outfile)

{

cout << "Couldn't open the file!" << endl;

return 0;

}

- Check whether a file creation succeeded.

- If the file creation failed, handle it appropriately. Don’t just print a horrible message like

Oops! Aborting!. Instead, do something friendlier — such as presenting a message telling users that there’s a problem and suggesting that they might free more disk space. (There are other reasons not covered in this book, such as lack of rights to the area of disk where the file is written — you need to perform application testing to locate all the possible reasons a file creation might fail and then provide error handling for each potential issue.)

Flagging the ios Flags

When you open a file by constructing a stream instance, you can modify the way the file will open by supplying flags. In computer terms, a flag is simply an indicator whose presence or lack of presence tells a function how to do something. The flag appears in the constructor when working with a stream.

A flag looks like ios_base::app. This particular flag means that you want to write to a file, but you want to append to any existing data that may already be in a file. You supply this flag as an argument of the constructor for ofstream, as shown here:

ofstream outfile("AppendableFile.txt", ios_base::app);

You can see the flag as a second parameter to the constructor. Other flags exist besides app, and you can combine them by using the or operator, |. Following is a list of the available flags:

ios_base::ate: Use this flag to go to the end of the file after you open it. Normally, you use this flag when you want to append data to the end of the file.ios_base::binary: Use this flag to specify that the file you’re opening will hold binary data — that is, data that does not represent character strings.ios_base::in: Specify this flag when you want to read from a file.ios_base::out: Include this flag when you want to write to a file.ios_base::trunc: Include this flag if you want to wipe out the contents of a file before writing to it.ios_base::app: Include this flag if you want to append to the current file pointer position of the file (which is at the beginning when you first open the file). It’s the opposite oftrunc— that is, the information that’s already in the file when you open it will stay there.

The FileOutput02 example, shown in Listing 1-6, shows how to use a flag to append information to the output of Listing 1-1.

LISTING 1-6: Appending to an Existing File

#include <iostream>

#include <fstream>

using namespace std;

int main() {

string filename = "../MyFile.txt";

ifstream check(filename);

if (!check) {

cout << "File doesn't exist.";

return -1;

} else {

check.close();

}

fstream datafile(filename, ios_base::app);

datafile << " There" << endl;

datafile.close();

cout << "File Written!" << endl;

return 0;

}

If the file exists, you want to close the file handle to it before you write to it by calling check.close(). You can then reopen the file for appending by adding the ios_base::app flag. The example outputs some additional text and closes the file.

You don’t have to type the source code for this chapter manually. In fact, using the downloadable source is a lot easier. You can find the source for this chapter in the

You don’t have to type the source code for this chapter manually. In fact, using the downloadable source is a lot easier. You can find the source for this chapter in the  If you try to open a file for writing by specifying a full path and filename but the directory does not exist, the computer responds differently, depending on the operating system you’re using. If you’re unsure how your particular operating system will respond, try writing a simple test application that tries to create and open a nonexistent path like

If you try to open a file for writing by specifying a full path and filename but the directory does not exist, the computer responds differently, depending on the operating system you’re using. If you’re unsure how your particular operating system will respond, try writing a simple test application that tries to create and open a nonexistent path like