After the Great War, Art Smith, The Bird Boy of Fort Wayne, remained in the United States Army Air Service as a test pilot flying the experimental craft first imagined during the recently concluded hostilities and now realized in Ohio. One such vehicle was a quadrotor named the de Bothezat Helicopter but known to the flight crews at Dayton’s McCook Field, as “The Flying Octopus.” As its nomenclature implied, the airframe supported four six-bladed rotors, that provided the lift, deployed on sweeping arms of cantilevered girders reinforced by a system of guy wires and turnbuckle stays. In flight, the helicopter very much resembled a roofed railroad truss bridge dislodged by a tornado. Maneuvering was achieved through another twin set of vertical props that the designer George de Bothezat named “steerable airscrews.” Two more fans mounted above the underpowered Le Rhone engine (soon to be replaced by a Bentley in a rotary configuration) were meant to provide additional airflow and cool the power plant.

Art Smith was one of only two men, the other being Major T. H. Bane, qualified to take the contraption aloft. The controls and instruments were particularly complicated. The aircraft mounted dual spoked wheels for banking, a yoke for the whole aircraft’s pitch and trim which was wired with six toggles to adjust each rotor’s variable pitch setting, a half dozen throttles, one regulated with one’s knees, and a set of foot pedals for yaw. The flap-like air brakes were engaged via an umbilical belt attached to the pilot’s waist and activated with a rotary motion of his hips during the landing. Though the airplane itself was scrapped in 1924, the control array is on display at the Smithsonian Institution.

Surprisingly, the airplane flew. Or more accurately, on 18 December 1922, the helicopter hovered two meters above the ground. The contraption proved to be a remarkably stable platform, due, perhaps, to its many angled lift rotors canted toward the center of gravity. In its year of testing, the craft successfully lifted off over one hundred times, eventually attaining a sustained altitude above twenty meters, and was able to carry up to four passengers to that height.

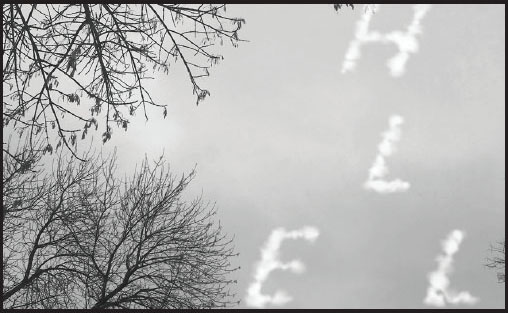

The early test flights demonstrated the craft’s ability to do little more than vertical takeoff and landing. Its lateral motion was dictated by the prevailing wind that would push the craft hither and yon in an uncontrolled fashion. Art Smith, in later flights, attempted to address the craft’s directional deficiency, going so far as to attach his skywriting mechanism with its panel of instruments to map the vectoring he sought to achieve. Pictured here, the result of his experimentation that fall, are the unstable remnants of erratic and abrupt course correction. An abandoned “HELICOPTER,” perhaps, or an aborted “HELLO” graced the sky over Dayton for a moment as the Octopus, generating fog from all of its many spans and booms, left a telltale tracing of its seemingly stable and steady and sustained flight.