From the air, the world, falling away below, grew so small. It always struck Art Smith, The Bird Boy of Fort Wayne, how diminished, how minuscule the people in the crowds of people who had come to see him fly became as he climbed. They shrank. Or, more exactly—collapsed, flattened, contracted. Even evaporated. Boiled down to nothing. He was aware of this and other optical illusions flying created. The forced perspective of this new kind of distance was proof that human eyes were not built to see clearly under such circumstances. Our eyes were not like those of the raptors, who could glimpse and target the smallest of the small growing smaller as they soared.

This effect never failed to amaze his passengers back in the early days of exhibition flying. Those observers would have been lucky to have climbed as high as the rooftop of a five-story building or the belfry of a church steeple. They squealed through the prop wash and roar of the engine, “Look, look!” their shouts scrambled and shushed. They gestured instead, squeezing the air between their closing fingers to pinch upon the ever-compressing image of a shrinking spectator below.

Art Smith had met Paul Guillow, a naval aviator, during The Great War, when together with other test pilots and instructors they developed the close comradeship of the airmen’s barracks in Ohio. This intense friendship went so far as to the creation of a tontine whose capital consisted of patent applications, blueprints, and aeronautical drawings of wing, engine, and fuselage design each individual club member had devised. Guillow imagined after the war that there would be a public interest in scale models of the life-sized aeroplanes he and his compatriots had built in barns and backyard sheds at the dawn of powered flight. Far from the war where the exigencies of combat were accelerating design modifications of the new fighter aircraft at the front, Art Smith and Paul Guillow experimented with the miniaturization of aeroplanes from the past, fabricating from balsa wood, tissue paper, dope, thread gauge wire and foil, the replicas of their flying machines.

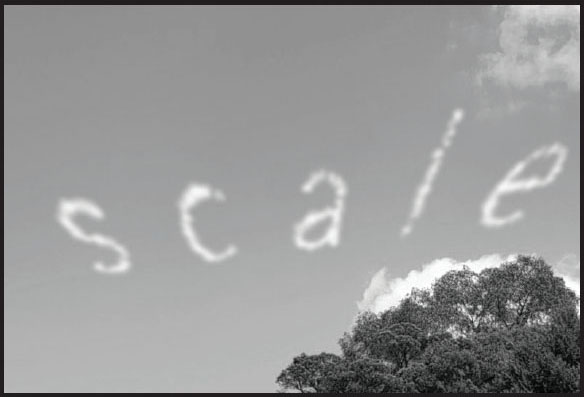

The war over, Paul Guillow went on to found the company that to this day bears his name. Guillow manufactures model kits of actual aircraft as well as simple penny gliders that when thrown with their pliant wooden wings warped to the proper degree perform rudimentary aeronautic maneuvers, barrel rolls and loops, as they sail through the air. Guillow engaged his former barracks mate and fellow tontine subscriber, Art Smith, to compose, in skywriting, advertising for the new company. Above Wakefield, Massachusetts, in 1925, Art Smith experimented, constructing the message, scaled scales, careful to retrace the schematic he had drawn, s c a l e, on a piece of gridded paper onto an unruled sky. From the ground, his airplane was but a mere speck in the heavens, a pinpoint, the nib of an invisible pen from which the letters billowed forth and then disappeared in an invented distance.

After all these years of “skywriting” it was still difficult for Art Smith to judge how his compositions appeared to the earthbound onlooker. From where he sat, he was lost in a maze of his own invention. He counted out the seconds during the long reach of an “l,” to the point where he felt the stroke should be stopped. The curves and arches and loops were more difficult to produce. He must hold a banking turn while monitoring his compass as it swung through the wide arch of bearings. In the midst of a witty sentiment, he was entangled and enveloped by the clouds, the fog, he himself had generated.

Your eyes can play tricks on you. They seem not to be calibrated to see, to comprehend size over great distance, a perspective now made readily possible by heavier-than-air powered flight. Art Smith would, the next year, mistake a light in a farmyard for the lights of the landing strip in Toledo. One night, he found in the depths of one pocket of his flight jacket a newly minted dime whose obverse bore the profile of Liberty in a winged cap though widely mistaken as portraiture of Mercury, the messenger god. He drew it out, and, out of his pocket, the dime’s silvered surface caught a flash of moonlight. That clear night, flying with the full moon riding on his wing tip, Smith eyed the planetary heft of that moon muscling into the sky and then, like that, he held up the coin, the thin little wafer tweezed between his fingers, held it at arm’s length, and saw it blot out any inkling of another nearby world in all that nearby closing darkness.