It was once believed the sudden but cyclical reoccurrence of the respiratory disease we know as “the flu” was brought on by the periodic orbiting of heavenly bodies. The Italian word, “influenza” reflected this suspected connection that the radiation generated by the stars “influenced” the health and well-being of its earthbound recipients.

In the early months of 1918, a pandemic influenza swept the globe. It has become known as the “Spanish Flu,” not because of its origin there but because Spain, a neutral country in the Great War, did not censor the morbidity and mortality rates as the disease took hold, creating the appearance that the flu persisted there and not within the borders of its combatant neighbors. In reality, one of the earliest outbreaks occurred in Haskell County, Kansas, in March of 1918.

Art Smith, The Bird Boy of Fort Wayne, then an instructor and test pilot for the United States Army Air Service, was dispatched from McCook Field in Dayton, Ohio, to Fort Riley, Kansas, where most of the camp was stricken by this novel and deadly strain of the disease.

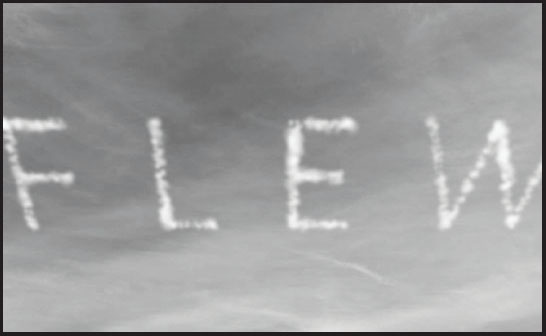

In an attempt to quarantine the decimated post while at the same time disguising the true nature and extent of the calamity and its casualties, Smith inoculated the sky arching over Fort Riley with this hom-onymic message. In the still pristine air over the prairie, the message persisted, could be read for miles. Unbeknownst to the incapacitated bivouacked below, the chemical makeup of the smoke had been altered, infused with a tincture of antiseptic Listerine in aerosol suspension. Its heavier-than-air hygienic ingredients separated out of the solution of shaped sterile clouds over the time it took to construct the word, rained down silently and invisibly upon the congregation of the ill and their beleaguered caregivers barely surviving on the infected ground beneath Smith’s feverish inscription.

At McCook Field, Art Smith had worked with engineer, Etienne Dormoy, on the early experiments in crop dusting, hauling aloft payloads of lead arsenate slurry to aerially apply the poison over a catalpa tree farm near Troy, Ohio. The target was a hawk moth, the catalpa sphinx caterpillar infesting the grove. The initial results seemed successful, the heavy metal mist being breathed in by the bugs’ accordion-like spiracles, wreaking havoc on its respiratory function, and plating their colorful carapaces with a grimy metallic coating that knocked them from the defoliated branches.

Flying over Kansas, Art Smith watched as, in the great distance, clouds piled up into the spectacular anvil-headed vaporous mountain ranges of an approaching front, the silent lightning within it tripping a telegraphy of bright bursts throughout the long line of relentless weather. Indeed, the dead and dying below were “under the weather.” And above it, in the thick occluded air, Art Smith, a devout Christian Scientist, circled and banked and dove and dipped, composing his kind of prophylactic prayer, an efficacious message to intercept and countermand the ill influences of that heaven domed above him. Seeded within the smoke, backlit by the green sunset filtered through the storm, sanded phosphorus ignited and oxidized, glittering as it burned within the words, creating a kind of smokescreen as the letters smeared into one another, propelled by the wind before the front. The writing became a silt of smoke, a fine flashing osmotic canopy of dust, another cloudy riddle absorbed into the approaching mass of clouds.