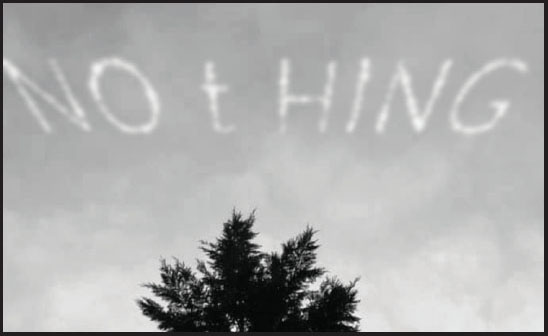

In 1902, Dr. Charles Otis Whitman, a zoologist of Chicago University, in an attempt to reverse the catastrophic collapse of the wild passenger pigeon population, sent a captive breeding pair to the Cincinnati Zoo in the hope that a rock dove there would foster the distracted passenger pigeons’ eggs. In 1910, Professor Whitman, working in his laboratory attempting to describe Columbicola extinctus, a louse thought at the time to be unique to the passenger pigeon and disappearing as the host species disappeared, caught a chill and died. Four years later, Martha, one of Dr. Whitman’s birds, died in Cincinnati, becoming the endling of her species. Shortly before that, the zoo, in a vain hope, commissioned Art Smith to survey the Wabash and Maumee watersheds of Indiana, serving as a scout in what was to be the final wild passenger pigeon round-up. For several weeks, he scoured the river valleys in search of any evidence of a tattered covey of the pigeon that was thought to have numbered in the billions only half a century earlier. Then, Audubon lost count of the number of flocks, flocks made up of millions of individuals, when he attempted to record their passage near Louisville. “The air,” he writes in Birds of America, “was literally filled with pigeons; the light of noon-day was obscured as by an eclipse; the dung fell in spots, not unlike melting flakes of snow; and the continued buzz of wings had a tendency to lull my senses to repose…” The skies over Indiana were now empty as Art Smith flew through them. As he banked his airplane, composing the O, he thought, perhaps, of the egg he had been shown, preserved in the collection of fossils and feathers at the funereal zoo. Years later, in 1947, long after Art Smith had died and was buried, the naturalist Aldo Leopold would compare the disappeared flocks to “a living wind.” Art Smith began to climb, climbing by means of a spiral ascent, in long wide-open circles. Leveling off at last, he could see the horizon all around him. He was high enough to make out the initial warping off in the distance, the curvature of the earth, its promised declivity. As he lined up his craft again and began the application of smoke to cross the T, he experienced, suddenly, a patch of rough air, a turbulence, invisible, that, nevertheless, from its sheer force of downdraft, aberrated his plotted course, spoiling the capitalization, abrading the message he was attempting to send through all that empty emptiness.