1914. The Great War begins in Europe. There, it quickly becomes evident that the utter devastation meted out by modern weaponry will be so pervasive as to lay desolate the great rose gardens of Europe. 1915. That spring, hybridists of all the Major Powers meet secretly in Switzerland to discuss the creation of a grand refuge for the flower far from the lethal battlefields and the now newly aerially bombed cities. Meanwhile, half a world away in Philadelphia, Art Smith, The Bird Boy of Fort Wayne, is engaged by rose enthusiast, George C. Thomas, later Captain Thomas of the United States Army Air Service, to initiate a campaign of public awareness and fund raising for the creation of such a botanical refuge in one of the far western states. Art Smith takes to the air after adapting his skywriting mechanism to produce a deep red effluent, imploring the curious onlookers to cultivate the most beloved bloom.

Smith and Thomas also modified Smith’s aeroplane to carry a cargo of rose petals, an apparatus mostly constructed of a netted hamper that when agitated proceeded to expel the petals. During a prolonged sweeping turn along the Schuylkill, Smith released his delicate cargo, creating, what was reported at the time, a crimson signature of flowers, a blood-red cloud curtain evocative of the noble carnage being spilled on the denuded plains of France and Belgium. The flowering trees along the river were in bloom, and the remnants of the raining rose petals clung to the native blossoms for days later until they too fell to the ground mixed with the now blown and spent native display.

Upon his return to the United States after his first successful tour of Japan in 1916, Art Smith, The Bird Boy of Fort Wayne, took to the air once more. His severe injury—a broken femur, sustained in the spectacular crack-up at Sapporo—was on the mend. He headed east, on several missions, one of which was to resuscitate the neglected drive to establish a sanctuary for rose propagation far from the botanical gardens of war-torn Europe.*

Again, he flew to Philadelphia to assist George Thomas in his campaign. This time he composed a message that extended the length of the Delaware River waterway, the airy letters drifting as they dissipated in the prevailing breeze decaying over the far reaches of the New Jersey shore. Once more, Smith followed, in the wake of the desiccating inscription, with an infusion of iridescent petals that drew a shimmering curtain in front of the setting sun. The petals were so buoyant and the drafts of air that day so stirring that the shower Smith unleashed seemed to levitate instead of falling. Stalling, it continued to rain down through the gloaming, giving Smith enough time to land his aeroplane on the Jersey waterfront and enjoy the sparkling drizzle of fragrant confetti. Unbeknownst to Art Smith that day, his craft served as an unwitting vector for an insidious invader. Concealed within the precipitation of roses was a stealthy stowaway transported from Japan, its eponymous beetle, Popillia japonica, that copper-colored clumsy flier discovered and scientifically confirmed a few months after Art Smith’s departure by a Rutgers entomologist in a Riverton, New Jersey, florist’s greenhouse.

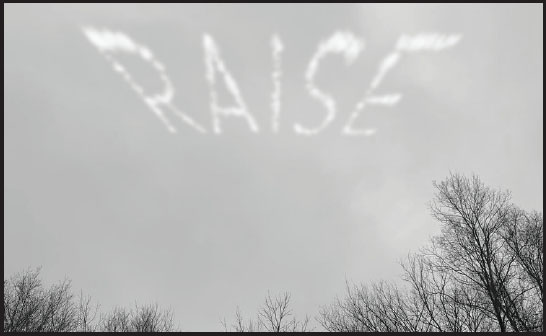

In the spring of 1918, the rose cultivars began arriving in Portland, Oregon, soon to be known as the “City of Roses.” The site of The International Rose Test Garden would grow to over four acres of terraced plots and sculptured beds. There would be nearly 10,000 plants and 600 varieties represented including the Rosa kordesii Rupert Brooke, named for the poet who died on his way to Gallipoli and is buried on the Greek island of Skyros. Art Smith, a long-standing proponent of the rose refuge, was transporting a bare root Rupert Brooke start with him as he installed the evocative message, above, in the dirty weather over Portland. |