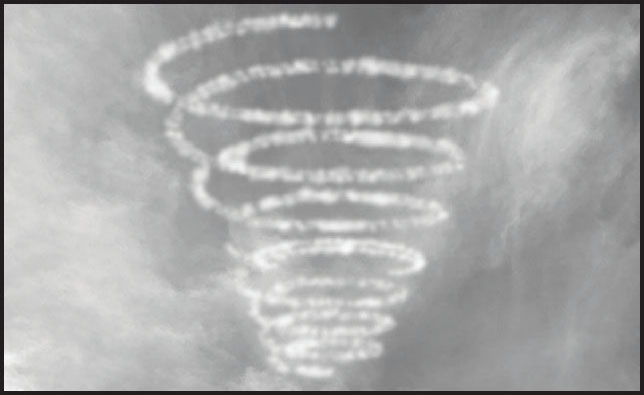

He called it “The Falling Leaf,” Art Smith, The Bird Boy of Fort Wayne, did. He had, many times, descended from altitude by such means, employed a spiral trajectory, either narrowing the loops as he approached the earth or widening the loops as he fell. In all those initial attempts in early aerobatics, however, he was unable to record the graceful decline; map the difficult maneuver in order for an audience to appreciate these daring initial experiments in the physics of controlled powered flight. In other words, the onlookers were unable to tell “the dancer from the dance” to quote W. B. Yeats, a poet Art Smith was known to admire. Perhaps this lack of the ability to inscribe the complicated exertion against and in tandem with gravity, circling through the transparent air, incited Smith to create “skywriting” in the first place! “The Falling Leaf” is seen here in the December night sky of 1915 at San Francisco’s Panama-Pacific Exposition. To record the stunt that night, he used intense light tracings that would score the overexposed photographic negatives of the under-illuminated event. He accomplished it by using burning phosphorescent fusees borrowed from the Southern Pacific Railroad Company, an extremely dangerous combustible to have on board his wood and canvas aircraft. The leaf he was thinking of, I think now, must have been the palm-sized maple leaf prevalent in his hometown in Indiana. And what with its fiery colors of autumn—the reds and oranges and yellows—a camouflage of flame while falling, the leaf, no doubt, suggested to him the pyrotechnical display he would create. I can see him now, transfixed, watching the whirling leaves landing one after one. Or, perhaps more accurately, he sought to mimic the motion of the cantilevered construction of the maple tree’s winged seeds, double samaras, with their elegant helical transcriptions as they spun to the earth through the late summer’s humid air. In any case, this stunt became Art Smith’s signature, literally, written each night in the sky over the exposition.

It is the “graveyard spiral” but also known as the “vicious spiral,” the “deadly spiral,” or, simply, the “death spiral.” This fatal spiral dive, initiated, accidentally, when a pilot flying in fog, night, or other visually obscured phenomenon is blind to the horizon. The sensory deprived pilot listens to the signals, illusionary signals it turns out, emanating from the inner ear. He feels that he is in level flight but losing altitude and reacts (he cannot help himself) to pull up. But in doing so, he only tightens the turn, accelerating into the banking turn his plane is already locked into. It creates a kind of vertigo for the plane. But that vertigo is kept from the pilot in the blind cockpit where the instinctual maneuver of “pulling up” feels like life-saving equilibrium. Trusting one’s “seat of the pants” over the feedback of flight instruments, a pilot over-corrects. He gets the “leans,” sensing he is level when he is not, he continues to compensate to the false whisper in his ear. It is paradoxical that the confused and confusing organ complicit in the service of the “death spiral” should be the inner ear with its corkscrewing cochlea and its braid of semicircular canals that sculpt in bone and tissue the very deadly flight path the ear fails to read or comprehend. Art Smith, The Bird Boy of Fort Wayne, trained with early, view-limiting devices, trained and then trained others to fly with instruments, to override the messages his own sensing apparatus mistakenly produced. Shown here, a controlled death spiral, very much like “The Falling Leaf” of San Francisco, over Dayton, Ohio, sometime after he began flying for the Mail Service. His “skywriting” transcribing, in a controlled manner, the nightmarish spiral for student observers on the ground. His own fatal crash, a few months later, would be ruled a pilot error. But it was a different kind of mistake, one of visual acuity not auditory derangement as he mistook the lights of a farmyard as aids to navigation at a landing field. Still, after all this time, a failure to recognize or respond to instrument readings is the most common cause of what we now call “a controlled flight into terrain.”

It might have been that Art Smith, The Bird Boy of Fort Wayne, first read W. B. Yeats’s poem “The Second Coming” in the magazine The Dial where it was first published in 1920. The Christian Science Reading Room in Fort Wayne did carry the magazine in its inventory out of the mistaken belief that it was still the Transcendentalist journal it was at its founding in 1840. Or did the book in which the poem was later collected, Michael Robartes and the Dancer, fall into his hands a year later in a Cleveland bookseller’s shop or the Allen County Public Library between sorties for the Mail Service or applications of skywritten advertisements? He would have been taken by the imagery of flight and flying encapsulated by the falcon and falconer as well as the evocation of the “widening gyre” the bird turns through in the poem’s opening line. The sublime apocalyptic symbolism would have struck a chord as the poem addresses the aftermath of The Great War’s traumatic disruptions. The bombing of cities from the air. Aerial dogfighting with rapid firing machine guns diabolically designed to fire in the clear intervals between spinning propeller blades. Fiery midair disintegrations of fragile and unstably tuned aircraft. Smith and many veterans read the bleak verses generated by the carnage. Sassoon, Owen, Brooke, Graves. The early optimistic elation that airplanes and flying promised seemed broken and exhausted as aviation and Art Smith settled into routines of hauling bags of letters through the air punctuated by the prosaic tattooing of the sky with advertisements for cigarettes and shaving cream. The center not holding. This lyrical curlicue was captured over rural Zulu, Indiana, in the summer of 1922 amidst the circling turkey buzzards and quarreling crows. A folly of exhaustion? A distracted doodle? An attempt to recapture some of the spent joy of his boyhood flight? A transcription of a sigh? A hieroglyph of a death wish?

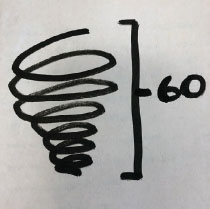

On Wednesday, March 18th, 1925, the deadliest tornado in the history of the United States cut through Missouri, Illinois, and Indiana. The Tri-State Tornado killed close to 700 and injured more than 2,000, damaging 20 cities, four of which were effaced from the earth. It was a fast moving storm, averaging 60 miles per hour as it moved diagonally from southwest to northeast. It traveled over 300 miles, in the five hours it was on the ground, carving a path that ranged from 1 to 3 miles in width. Had there been satellites, the ruled straight-edged course of the storm’s destruction would have been visible from space. And even a few months after the event, that scored course remained visible to Art Smith, The Bird Boy of Fort Wayne, who, from a mere mile aloft, easily tracked the storm’s irresistible vector as it plowed through the mostly rural landscape. The shadow of his Jenny fell on the actual trued black furrow in the fields below still papered with debris, tangled metal wreckage, alluvial fans of masonry, clapboard sticks, and swaths of shingles. At the end of his reconnoitering near Princeton, Indiana, where half the town was destroyed and the Heinz factory flattened, Smith pulled up, performed a slow circling climb into thinner and ever thinner air, probably not even aware that he had initiated the telltale smoke of his skywriting, and disappeared there, above a high ceiling of reddish cirrocumulus clouds also known as a mackerel sky.