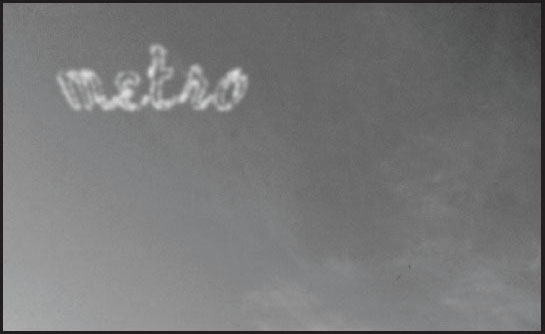

July 15th, 1915, was Metro Day at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, honoring the contributions the Metro Pictures Corporation had made to the fair. Francis X. Bushman, president of the company, led the Metro delegation through the throngs on the Avenue of Palms to the Court of the Universe where officials of the Exposition received them. Speeches were given and tokens exchanged. Edward A. McManus, general manager of the Hearst-Selig News Pictorial service, said, “The one striking new feature of modern life is the wider and wider diffusion of information. The press hitherto has been a great instrument of this beneficent work. With the supreme inventive genius of modern men the press has been supplemented by the moving picture, which not only gives the same wide presentation of the subject, but which visualizes it in presenting it pictorially, and which has established itself a new and vital educational force in the modern civilized community.” The party then proceeded to Filmland on the Zone, the Exposition’s entertainment area, where a beauty contest was in progress. Twenty-five aspirants posed for the camera. The evening was completed when Art Smith, The Bird Boy of Fort Wayne, mounted his illuminated aeroplane and, in the still evening sky, climbed to 3,000 feet only then to descend in a crazed looping spiral corkscrewing dive with the fusees on his wing sparking and flashing as if indicating the foreshadowing of a fiery and fatal crash. Thousands below watched in amazement. Thousands more watched from San Francisco’s surrounding hills. But all witnessed finally a carefully designed but thrilling aerobatic stunt. When safely on the ground, Smith was presented with a gold medal by Francis X. Bushman, the head of Metro Pictures. The presentation was not filmed. Later, the negative plates were developed. The overexposed still photography record of his recent flight, that seemingly aborted night flight, was developed. The message in the madness could finally be read. There, in a cursively connected script of flare and fire, was the salutation, M E T R O, etched in bright white light into the black night, enveloping the whole wide San Francisco Bay and the cities and towns on its shores and even in the hills and valleys beyond.

It is said that in one year when the population of the United States was 90 million, 17 million saw Lincoln Beachey, The Man Who Owns the Sky, fly. A San Franciscan, Lincoln Beachey, The Master Birdman, was the obvious first choice to be the featured stunt aviator at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition. He opened the fair with an amazing feat, taking off inside the Machinery Palace on the exposition grounds, flying his Curtiss Pusher at 60 miles per hour, and landing it, all within the confines of the hall. Art Smith, The Bird Boy of Fort Wayne, assisted Beachey’s performances, an understudy of sorts, who in his midget race car would chase the low flying master along the Avenue of the Palms. On March 14th, Beachey launched out over the Bay in his new monoplane to perform his famous maneuver, a series of inside loops. But the overpowered airplane’s controls could not handle the torque and the strain. The plane crumpled and fell into the water between two Navy ships. He survived the crash, the autopsy later revealed, but was unable to escape the harness. He drowned. Art Smith took his place, flying the daily demonstrations and the nightly skywriting shows spotlit by the General Electric Scintillator emanating from the Tower of Jewels. But before that, he needed to practice, to attempt to reach the skill of his recently deceased mentor and friend, Lincoln Beachey. “An aeroplane in the hands of Lincoln Beachey,” Orville Wright had said, “was poetry.” Smith needed a place to learn to write in the sky. He needed a place, too, to steady the nerves, tamp down the tide of rising fears, to be alone with his machine in the air and the dynamic physics of not falling even as you fall. He discovered, twenty miles south of San Francisco, the necropolis of Colma, California. Colma, the city of cemeteries. After the earthquake, the city of San Francisco had closed the cemeteries in the city and evicted the dead. Beachey had been buried somewhere down there. The fields were a patchwork of tombs, mausoleums, ossuaries. Art Smith bombed the fields with flowers. Then with the wings of his aeroplane outfitted with small smudge pots, railroad flares, roman candles, Art Smith wrote for the dead. Again and again, he wrote, writing, always beginning in a profound dive, mimicking an out-of-control tailspin to make his gyrations look erratic, but, in reality, he was spelling out, in the exhaust, little prayers, letter to letter to letter, each ligature a bridge, a reprieve, each serif another breath caught and another, a stair-stepping signature. He wanted to feel the weightlessness as he fell, sense the levitation of the smoke as it rose up behind him and was propelled upward by the rising heat of the highlands below. Somewhere down there was what was left of Beachey and up above were the streamers of smoke, the trail of sparks, braiding together like wraiths, like ghosts, like stars, the rising residue of colmacolmacolma.