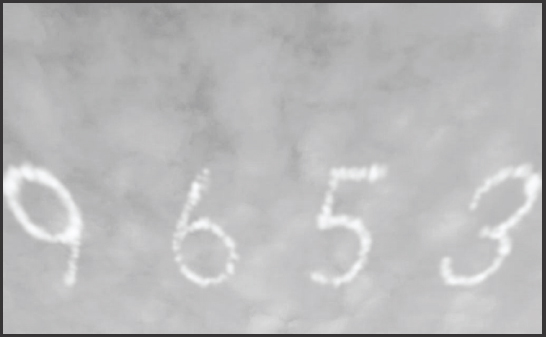

On Christmas, 1921, President Warren G. Harding commuted the sentence of Socialist Eugene V. Debs who had been imprisoned since 1919 in Atlanta for sedition. Debs arrived home in Terre Haute, Indiana, three days later and was met at the rail depot by thousands of cheering Terre Hauteans. At that moment, Art Smith, The Bird Boy of Fort Wayne, was aloft, over the city known as The Crossroads of America, the intersection of highways 40 and 41, affixing the number 9 6 5 3 in frigid pristine Indiana air. This is not an estimate of attendance or of the crowd size gathered on the ground, but the number given to the famous agitator and pacifist (now speaking animatedly from the open vestibule platform of the observation car below) by the Federal Bureau of Prisons. As Convict #9653, Debs had run for President of the United States, again, his fifth attempt, the year before, garnering nearly a million votes while behind bars. Art Smith had heard of Debs, but had not voted for him. In fact, there appears to be no record of his having voted for anyone at all. He had been and would be in the future on the move, never establishing a permanent residence really. And, as he was often perched high overhead, flying over precincts and wards, more often than not, he felt detached from the earthbound goings on beneath him. Even though he allowed the epithet of “The Bird Boy of Fort Wayne” to remain connected to his name, trailing Art Smith like the new advertising banners he had begun to deploy behind his aircraft to augment his skywriting, he no longer felt attached to that place as he once did. A Bird Boy, yes, but of Fort Wayne, less and less. Politics and the voting that accompanied it, he understood, was attached to place. No, it had dawned on him a while ago that he was now, more and more, a citizen of the sky. Debs had been sentenced to ten years hard labor, and he had been disenfranchised for life for his seditious speech at Canton, Ohio, during the Great War. In many ways, Debs too was as disconnected from the world as Smith was now. Even bound he had been unbound, not local but global. Rootless.

The Root Glass Company had originally lured Art Smith to The Crossroads of America. In 1915, the company entered a contest to design and exclusively manufacture a new proprietary bottle for the Coca-Cola Company. Their design, inspired by the ribbed and ellipsoid contour of the cocoa plant seedpod, shown here,

won the competition handily and their “hobble-skirt” bottle, cast in the distinctive German Green glass, was an instant success, and the container remains connected to what it contains even today a century later. In 1921, the patent for the product was about to expire. Coca-Cola and Root embarked on a campaign, the first of its kind, to have not just the name or slogan or text about a product trademarked but also its actual package. Its vessel would speak the protected name. A shape would be a brand. To that end the companies hired a semi-ridged dirigible, similar to the one shown here,

to hover over The Crossroads of America and, through an act of subliminal free association, have the public below connect the shape of the blimp to the bottle to the seedpod to the product. Art Smith contributed to the effort circling the oblong balloon and skywriting the company’s name in such a manner as its oblong O’s seemed to effervesce, floating, making a halo of haloes around the airship.

The skies over Terre Haute, The Crossroads of America, bustled in the closing days of 1921. Eugene V. Debs had been released from prison and been welcomed home a hero. The Root Glass Company had captured lightning in a bottle and the bottle itself had become a kind of lightning. Hulman & Company also was headquartered in Terre Haute, a wholesale grocery and manufactory of leavening agents. Now as the company wished to expand into the retail market, they considered a rebranding as well. Art Smith experimented with his new idea of a more permanent form of “skywriting.” He would write his message in bold letters printed on giant panels of silk. The message? The chemical formula for the company’s signature product, baking soda. The streaming silk banner unfurling and flapping in Art Smith’s wake dictated that he create, in the face of the banner’s new and unique aerodynamics, whole new techniques and tweaks for steering and stirring the aircraft for sustaining controlled flight. The buffeting was an amplification of the popping and puckering of the scarf he wore around his neck that would slap him, wrapping around his head and blinding him during gravitational gyrations caused by his acrobatic maneuverings. The tail of letters had a life of its own in the slipstream. But flying with a banner was in no way as challenging as the actual production of letters out of thin air. He easily set his stick and throttle to a kind of automatic course, a slow broad circle over The Crossroads of America with the actual crossroads below serving as a kind of center on which he pivoted. It wasn’t challenging to fly this way simply hauling the letters, letters that seemed nonsensical to him, lugging them through the lower thicker air. And he could continue to display the advertisement even into clouds, clots that rose into lofts of white wispy loafs, that accumulated and expanded into billowing banks and bluffs in which he would disappear only to reappear, his trailing message intact like a ticker tape threading itself through gloved fingers. There was that. He didn’t need an empty sky to promote this leavening agent. Hulman & Company would rename the baking soda Clabber Girl in the New Year. And he would be back with another banner calibrated to the new name, churning and chugging through an undulating cloudscape, a curdled buttermilk sky.