A year before his own death, Art Smith, found himself in western Ohio at the service of First National Pictures, advertising with his skywriting the company’s new moving picture, The Lost World. His mission brought him over the Little Miami River valley to The Land of the Cross-Tipped Churches, a farming region settled by immigrant German Catholics who still spoke a Westphalian, Oldenburgian, and Lower Saxonic dialect, an isogloss, centered around the Grand Lake St. Mary. Minster, Fort Loramie, St. Rose, Montezuma, St. Henry, Sebastian, Cassella, Chickasaw, and Maria Stein, all these towns featured 19th-century red brick Gothic Catholic churches with their steeples topped with crosses. Art Smith could navigate the valley by means of steeple, using the spires as a kind of slalom pylon, banking, vectoring back and forth over the rich grid of quilted farmland spread out between the towns. He was flying a new WACO 7 biplane, shaking down the prototype for the Advance Aircraft Company, the manufacturer, headquartered just a few miles north in Troy. The Lost World, a silent movie, was adapted from a book written by Arthur Conan Doyle who appeared in the front piece of the film as himself, introducing the trailing adventure. The movie concerned a scientific expedition to a lost and forgotten plateau in Venezuela of intimidating geology, ancient flora, and prehistoric beasts, dinosaurs of all kinds. Smith had been told by the accounts office at First Republic that Doyle himself, without revealing the source as a Hollywood movie, had taken test reels showing the various dinosaurs fighting and grazing and flying to a meeting of the Society of American Magicians. The audience, which included Houdini, was astonished by the extraordinary lifelike visuals concocted by the trick photography. The stop-action animation effects were created by Willis O’Brien who years later would place an articulated puppet, King Kong, on a model Empire State Building attacked by a swarm of live split-screen projected Naval Reserve Curtiss O2C-2 biplanes. Art Smith would not live to see that monster’s death, but now he sat stone still, amazed in the darkened theater in Celina, Ohio, by the sight of the rampaging allosaurus attacking a family of terrified triceratops. He could, if he thought about it and if he looked very closely, see the slight twitch in the joints and limbs of the models as they moved, skipping from one frame of film to the next, but it was mostly seamless, this illusion of movement, how the eyes and the brain smoothed things over in the dark, skipping stone to stone, like his plane’s invisible ligature from one inanimate and monstrous letter to the next until it made sense.

Art Smith thought that, from a distance, the holey, moth-eaten exhausted strokes of his message looked a lot like the slivers of bone, splinters of wood, shards of marble, threads of fabric, locks of hair, or crumbs of cartilage on display at The Shrine of the Holy Relics in the town of Maria Stein. He had a whole week in The Land of the Cross-Tipped Churches, writing each day on the erased and refreshed vault of heaven overhead, a rosary of quirky quickly decaying letters commanding the volk below to attend this strange new movie. By the time he landed his WACO in a pasture or gleaned field—this was northwestern Ohio after all, full of flatness, that had been, at one time, the vast flat floor to an ancient inland sea after having been scraped flat by an eon of sanding by tidal waves of ice age glaciers—to visit the towns he daily flew over, he could regard his melting handiwork, gauge the remnants of his writing in the sky, now shattered fragments, scratches, smears. On one such landing he poked his head into The Shrine with its colorful and ornately carved side altars and reliquaries. Several Sisters of the Most Precious Blood knelt in a continuous vigil of veneration, murmuring prayers toward a forest of host-encumbered monstrances and ostensoria. There were the displayed relics but also everywhere else, in the aisles and the alcoves, there were cartons and crates of relics, shipped to The Shrine for safety as the Great War in Europe bloomed and churches there were consumed in the bombardments and conflagrations. Now, in 1925, there were no churches to return the bones to and The Shrine was becoming a parody of archeology, buried in artifacts with no spoil at all.

After finishing that day’s application of L O S T W O R L D, Art Smith glided smoothly downward, landing in a vast field outside of the town of Maria Stein that he soon discovered was the test track for the New Idea agricultural implement factory. As he descended, Smith saw several teams hauling the New Idea manure spreaders, their ground driven gears and axles rotating the flails and paddles at the rear of the wagons that launched the chaff of agitated chopped manure and broadcast it in wide arches in their wakes. He landed into the wind, of course, and through the layers of rich ripe and ripening smells, skipping over the slick, wet treated furrows below and jinking around and over the lifting roiled columns of steaming clouds of dust to find solid ground off in a far corner of the field. On the ground he looked back over to where the machines were working, the dung eruptions’ acrobatic percolations, amused by this other kind of terrestrial “writing” spewing from another tail end. The “new idea” had been another use for the wing, the winglike paddles set at odd angles that aerated, scooped, and threw the wide-ranging shit.

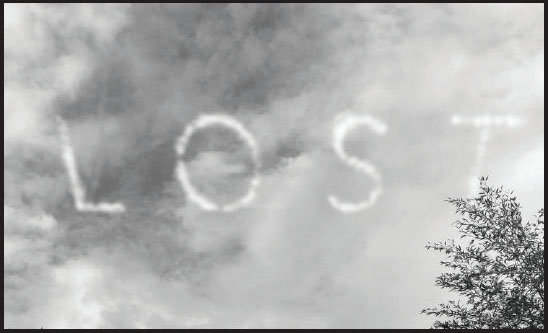

The first prehistoric beast seen by the explorers in the movie The Lost World is the flying reptile pteranodon. Art Smith, The Bird Boy of Fort Wayne, on the last day of skywriting advertisements for the film above the villages of western Ohio spelled out the name (from the Greek for toothless wing) of the soaring dinosaur. The pteranodon circles above the Venezuelan plateau of The Lost World, working the invisible thermals, Smith knew, with its voluminous ribbed wings spanning over twenty feet, half the length of wingspan of his own WACO 7. Its sleek head looked like a missile, the long sharpened beak blending back into the narrow skull topped with tapering dorsal crest of some kind, like the vertical rudder on a plane. How strange it all was. Smith concentrated on the spelling. He had made several mistaken efforts already. The fourth and final effort is shown here. The name was strange. Foreign. From another world itself. All vowels and a bizarre unknown digraph. And what was stranger, Smith asked himself, the haunting image captured on film or knowing that the articulated model of the beast represented a long lost reality of the fossil record? The pteranodon had once soared using the same convection and physics that were second nature to him in the air over Ohio.

Later that year, The Lost World would become the first movie to be shown to passengers on a regularly scheduled airliner. Imperial Airways, flying from London to Paris, presented the nine passengers on a Handley-Page O/400 the fantasy film of forgotten time. The plane, a converted bomber constructed of canvas and wood, was a dangerous setting to show the movie with its highly flammable nitrate film stock. A few months before, Art Smith, leaving The Land of Cross-Tipped Churches, devised one last signature to affix above the Maumee River Valley, the M O V E being torpedoed by a dive-bombing “i.” The print of The Lost World, having been a hit with its multiple showings in Celina, was now being transported by another WACO plane, the brand new WACO 8, the company’s first cabin craft, a big biplane seating six, to Toledo, the big city to the north on Lake Erie. Art Smith, The Bird Boy, escorted the ungainly 8 in its early evening departure, having already inscribed his cryptic farewell to the towns below. Later that year, upon hearing of the news from Europe that they had shown The Lost World movie in a moving airplane, he remembered his own flight that night, starboard and slightly trailing the bumbling big transport as it made its jerking lurches and inarticulate stuttering stalls to altitude. He remembered the flickering of illumination, the flashes of light he caught sight of through the big cabin windows of the 8 and the dark silhouettes inside, transfixed, staring dead ahead, spellbound, lost.