24

We’re Only Ordinary Men

What Cultural Celebrities Orbited Pink Floyd?

Rock groups comprise a strange fraternity. Bands with much in common musically or politically often don’t get along personally—see Oasis’ Gallagher brothers and Blur’s Damon Albarn, or the Velvet Underground and the Mothers of Invention—white seemingly strange bedfellows can form strong friendships. For instance, Alice Cooper, Micky Dolenz, Harry Nilsson, Jesse Ed Davis, and Keith Moon were all part of John Lennon’s mid-seventies retinue.

In their more than forty years in the rock underbrush, the members of the Pink Floyd encountered high and mighty, high and low, and high and sober showbiz folks with plenty of tales to tell. Here are stories of some of their encounters.

Douglas Adams

Writer, musician, philosopher, actor . . . Douglas Adams, a true Renaissance man, interacted with many of the coolest countercultural figures of the 1960s and 1970s, counting among his friends and collaborators Pink Floyd, the members of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, Monkees guitarist Michael Nesmith, and singer Gary Brooker of Procol Harum.

Just trying to make his way as a writer in the early 1970s, the Cambridge-born Adams hooked up with Monty Python’s Graham Chapman, wrote a few skits for the show, and even appeared in two sketches of the group’s last (non–John Cheese) series.

After various careers in other fields, he found the true outlet for his writing with The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, first a BBC radio series in 1978 and later a five-book series that expanded to film, comics, and even computer games. He also wrote Doctor Who episodes.

Adams regularly worked references to Beatles and Pink Floyd songs into his work, and counted fellow Cambridge native David Gilmour as a good friend. Adams, Gilmour, and Nick Mason shared a taste for auto racing.

As a birthday present to Adams—a left-handed guitarist who suggested The Division Bell as the title of the band’s 1994 album—Gilmour and Mason invited him on stage to play along with the band at their London show at Earls Court on October 28, 1994.

Adams moved to California in 1999 and passed away there of a heart attack in 2001 at age forty-nine. His official biography, published in 2003, is titled Wish You Were Here.

The Beatles

The young members of the Pink Floyd were jazz and R&B fans first and foremost, but even they fell under the spell of the Beatles. The Merseybeat phenomenon changed the landscape and blasted open the music scene, even for converted jazzers and blues freaks trying to become proper pop groups.

Syd Barrett, more than the other Floyds, embraced both the emerging underground and the notion of pop songwriting. The rest of the band, realizing that their young leader was the only one with an idea for slicing through the pop music jungle, fell in line.

While the Beatles were already international pop stars by early 1966, they hadn’t stopped checking out what was happening below sea level. Paul McCartney, in particular, was a benefactor of the London underground, lending financial support to the Indica Bookstore and the International Times, both of which trumpeted the Floyd’s efforts. (John Lennon also, later, donated to IT.) These subterranean connections made the Beatles and the Pink Floyd fated to come into contact.

It’s unlikely that the Beatles played any part in getting the Floyd signed to EMI subsidiary Parlophone (the Fabs’ label) in 1967, but their former engineer, Norman Smith, was lobbying for bands he could produce, and had some pull.

McCartney had checked out and enjoyed the nascent Floyd at the Roundhouse (“dressed as an Arab,” noted the press reports) on November 15, 1966, then again at the UFO club’s premiere on Friday, December 23, 1966. A tripping Lennon visited the Fourteen-Hour Technicolor Dream on April 29, 1967. It’s unlikely, however, that he stayed around long enough to hear the Floyd’s set, which took place at dawn after the band arrived from another gig earlier that evening.

On March 21, 1967, ten days after “Arnold Layne” was released, Norman Smith brought Syd, Roger, Rick, and Nick into Abbey Road for a short “meeting” between his new band and the Beatles. Smith was really pulling a favor; the Beatles rarely had any visitors in the studio. On this evening, the Fabs were working on overdubs for “Lovely Rita,” and as an added benefit, John Lennon was—unusually at Abbey Road—stoned out of his gourd.

While Hunter Davies in The Beatles characterized their meeting as a series of “half-hearted hellos,” Nick Mason was a bit more loquacious on Inside Out: “The music sounded wonderful, and incredibly professional, but in the same way we survived the worst of our gigs, we were enthused rather than completely broken by the experience. . . . There was little if any banter with the Beatles. We sat humbly, and humbled, at the back of the control room while they worked on the mix.”

Some have accused the Fabs of ripping off sounds coming from Floyd’s sessions, and others believe that Barrett & Co. could have taken things they’d heard from the Beatles down the hall. Both scenarios are possible, but unlikely; there’s little evidence to support either argument.

The Fabs had already experimented, by the end of 1966, with backward recording, random noise, Indian instrumentation, treated keyboards, vari-speed recording, double-tracked vocals, and sound effects, and their lyrics and melodies were the best in the field.

The Floyd were still new to the studio and in a similar position to the Beatles in 1963: recording their live set and a few new songs that rarely, if ever, were played at gigs. But PF’s own musical direction was already laid out in a diametrically opposite direction from that of the Beatles. Its rock was heavier and its folk folkier, though Waters later would borrow an approach and a few ideas from John Lennon.

The two bands rarely met, although both continued to work at Abbey Road during the rest of the 1960s. The Floyd were often on tour, and often were forced to record hurriedly. Once Piper emerged, however, McCartney reaffirmed his interest in the group and its ability to explore avant-garde areas in which his Beatle cohorts weren’t necessarily interested.

Decades later, Macca would work on multiple occasions with Barrett’s replacement, Dave Gilmour, who had taken inspiration from George Harrison’s guitar sounds, particularly on Abbey Road.

Kate Bush

British pianist and singer Kate Bush, born in 1959, was already writing songs by her early teens. Her work has always contained a variety of styles and influences, making her a progressive-rock-inspired songwriter. She incorporates elements of modern dance, spiritual seeking, humor, and classic literature into her work; few other artists could (or would) write songs about Joan of Arc, Wilhelm Reich, and Adolf Hitler.

Perhaps this far reach is part of what attracted David Gilmour to her music; he heard a demo tape she made in the early seventies and was impressed. Gilmour helped her make a more polished demo and eventually played a role in EMI’s decision to sign her in 1974.

At age fifteen, she wasn’t ready to record a proper album, so she spent time gigging with a hand-picked band, taking dance lessons, and writing songs. Her first album, 1978’s The Kick Inside, produced a British number one single in “Wuthering Heights,” the first-ever British number one record written and performed by the same woman.

Gilmour has retained ties with the eccentric and singular singer over the decades, singing backup on 1982’s The Dreaming and adding guitar to The Sensual World in 1989. (Pink Floyd collaborators Michael Kamen and James Guthrie also worked on her 2005 Aerial double CD.)

The two appeared at The Secret Policeman’s Other Ball in 1987, with Gilmour backing Bush on her 1985 monster hit “Running Up That Hill,” a song that Gilmour has quoted during the occasional PF show. During a 2002 Gilmour gig in London, Bush took the stage for a version of “Comfortably Numb,” singing the part created on record by Roger Waters.

Ms. Bush remains close to Gilmour and continues to publicly acknowledge him for his contributions to getting her career off the ground.

The Damned

What do Pink Floyd and a first-generation British punk band have in common? Just one album.

The Damned were the first British punk rockers to release a single, 1976’s “New Rose.” While they were certainly in tune with the tenor of the times, some hint of the band’s 1960s sentiments emerged on the 45’s flip side, a high-speed recasting of the Beatles’ “Help!”

When Stiff Records considered producers for the band’s second album, one name that came up was Syd Barrett, who was Damned guitarist Captain Sensible’s hero. Unfortunately, Barrett wasn’t available, even though the Sex Pistols, also fans, had tried to smoke him out in Cambridge.

The Damned were set to record their album, eventually titled Music for Pleasure, at the Floyd’s Britannia Row Studios. Perversely, drummer Nick Mason ended up with the production assignment.

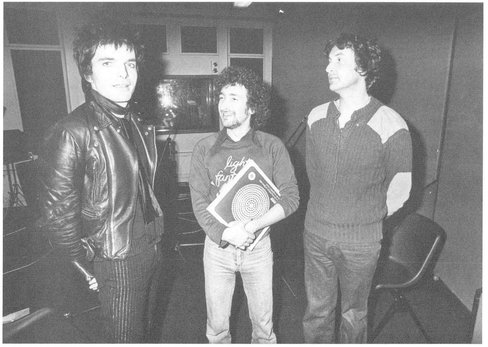

Nick Mason looks a tad uncomfortable with the Damned’s Brian James and DJ Nicky Horne during recording sessions for the Mason-produced Music for Pleasure. The album was panned and James soon left the band. Photo by Erica Echenberg/Redferns

Arguably the least “musical” of the Floyds and certainly the least like Barrett, the affable skinsman seemed a ridiculous choice to marshal a punk rock band into the studio (despite previous experience producing Gong and Robert Wyatt), but the band didn’t have much say.

The band and Mason got on fine personally, though they had little in common. The Damned’s way of working, however—quick, dirty, and few if any overdubs, amid an endless series of juvenile jokes—was in complete opposition to Mason’s methods, both in the Floyd and with his outside production assignments. The group hated the album, and so did the press.

Bob Geldof, K.B.E.

Irish sextet the Boomtown Rats were perhaps the first commercial pop-punk band. Each of their first ten singles, beginning in 1977, hit the British Top 40, using a hyperactive, cartoonish style that blended punk energy with pop songwriting dynamics.

Lead singer/songwriter Bob Geldof would have seemed an odd choice to have anything to do with an old-guard band like Pink Floyd, but when The Wall was optioned as a film in 1981, a bankable star was needed to play the character of Pink. At that point, the Boomtown Rats were among the biggest bands in Britain, and Geldof was a pinup with charisma.

Though Geldof had never worked in film, his screen test was apparently excellent and he was game for the film’s more difficult scenes. This was, however, his only feature film as an actor; he would find music (and, eventually, philanthropy) more interesting and less taxing than shaving off all his body hair, being painted with pink slime, and starring in a film featuring music by a group he couldn’t stand.

Eventually Geldof became the first rock star since George Harrison to take a starring role in eradicating poverty, helping write and produce the 1984 Band Aid single “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” Eventually Geldof’s project became Live Aid, two rock concerts (in London and Philadelphia) held on July 13, 1985 to help raise funds to feed the hungry of the world. The Floyd weren’t playing together at that time, though; having done many charity shows in the past, they regretted not being at Live Aid. Two decades later, the Floyd did help out Geldof, who by now had been knighted for his anti-poverty efforts, astonishingly reuniting for a short set at Live 8 on July 2, 2005. It was their first gig together since the four had played The Wall in 1981.

The quartet showed no animosities, though pushing and shoving had certainly happened behind the scenes. Galvanized to action by an uncharacteristic Waters phone call to Gilmour, Pink Floyd played five classics, three from Dark Side (“Speak to Me,” “Breathe,” “Money,”) as well as “Wish You Were Here” and “Comfortably Numb,” during which MTV showed its everlasting commitment to music by cutting to a commercial during Gilmour’s guitar solo.

Geldof’s response to the Pink Floyd “reunion”? “Not that I can stand you cunts, but you’ve made an old retro punk very happy. ‘Cos I never liked the music, really.”

Stephane Grappelli

Violin legend Stephane Grappelli (1908-97) was one of the greatest European jazzmen ever. A CV as varied as his—he worked with Django Reinhardt, Paul Simon, Yo-Yo Ma, bluegrass picker David Grisman, and Yehudi Menuhin, among others—would naturally have to include a Pink Floyd session.

Urbane, sophisticated, and well dressed, the string virtuoso first made his mark as the violinist with the Hot Club Quintet of France in the 1930s and 1940s, establishing unexpected musical and personal rapport with earthy, nearly illiterate gypsy guitarist Reinhardt. Despite having little in common with him, Grappelli added a solid, swinging, melodic sense to Django’s fiery playing, making this odd couple of jazz one of the most charming and thrilling duos in musical history.

Following Django’s death in 1953, Grappelli went his own way, collaborating with jazz giants Duke Ellington, Gary Burton, McCoy Tyner, Phil Woods, and Barney Kessel, as well as fellow violin legends Jean-Luc Ponty and L. Subramaniam.

During 1975, he and Menuhin—the finest classical violinist of his generation but also a devotee of jazz, pop, and Indian music—were at Abbey Road Studios recording a set of 1930s popular songs arranged in chamber style. Finding these two musical giants in the same studio where they were laying down Wish You Were Here, the Floyd thought it might be fascinating to have both of them on a track.

While Menuhin declined to participate, Grappelli (after negotiating a session fee said to be three hundred pounds) set up and began sawing away. The intention was to put his work at the end of “Wish You Were Here,” and some folks swear that they can hear the fiddle. The Floyd themselves don’t seem to think that Grappelli made the final mix, and didn’t credit him on the album sleeve in order to avoid trivializing him.

Gilmour noted in a much-quoted interview from 1999 that part of the session with Grappelli involved “avoiding his wandering hands. Was he gay? I don’t think many people would argue about that.”

Grappelli, who passed away in 1997, is interred at the same Paris cemetery that holds the mortal remains of Edith Piaf and Jim Morrison.

Jimi Hendrix

The Pink Floyd and Jimi Hendrix were certainly aware of each other from their travails in the London club scene starting in 1966. The two acts didn’t cross paths until 1967, though, by which time both were working on their first albums.

On May 29, the Floyd, Hendrix, and the Move all played a disastrous gig in a barn in Lincolnshire, a show “celebrated” for its horrid smell, terrible equipment, and crooked promotion. Not long afterward, Hendrix caught the Floyd at the UFO.

That summer, both bands engaged in abortive American tours. The Pink Floyd’s run in the U.S. ended ignominiously when Syd Barrett flamed out in California, while Hendrix was thrown off the Monkees’ tour (he’d been personally recruited by the band’s drummer, Micky Dolenz) after some fans objected to his sexually suggestive stage antics.

Pink Floyd and Hendrix (and the Move) met again on a U.K. package tour that began on November 14, 1967. While the Floyd, avant-garde and somewhat arch on stage when outside of London, had already begun to lose face (and bookings) due to Syd Barrett’s worsening mental state, Hendrix—the headliner, with years of experience on the R&B scene—had established the necessary chops and flair to entertain even the most provincial of fans.

Hendrix referred to the group’s troubled guitarist sardonically as “laughing Syd Barrett,” but apparently the rest of the band got on well with all three members of the Experience.

The next year, at the start of their second U.S. tour, the Floyd found themselves in New York without their promised stage gear. Hendrix, in Nick Mason’s words, “saved us ... he sent us down to Electric Lady, his recording studio and storage facility on West Eighth Street, and told us to help ourselves to what we needed. There are some real rock ‘n’ roll heroes.”

Barrett’s replacement, David Gilmour, was a huge Hendrix fan, right down to the Fender Stratocaster guitar, and several pre-Dark Side Floyd tracks (notably “Fat Old Sun” and “The Nile Song”) betray a strongJHE influence.

Petit, Nureyev, and Polanski

Roland Petit, director of the Ballets de Marseille, an unlikely Pink Floyd fan, contacted the band in 1970 with the idea of a collaborative project. The Floyd, all fans of the continent, were happy to take the opportunity to go to France.

Petit came up with the idea of the band providing music for a balletic interpretation of Marcel Proust’s novel Remembrance of Things Past. That project died, in part because none of the members of the Floyd could be bothered to finish reading the lengthy and somewhat difficult book.

Eventually the Floyd worked with the company for a week in 1972, jamming “Careful with That Axe, Eugene” and “Echoes,” but not enjoying the experience very much; all four members of the band were uncomfortable with tailoring their performance to the timing of the dancers.

Some time after this gig, Rudolf Nureyev, the world’s greatest and most famous dancer, organized a lavish lunch/planning session at his English home for either a filmed ballet of Aladdin or a ballet-cum-soft-core-porno-rock-opera Frankestein (nobody was quite sure which). Waters, Mason, and manager Steve O’Rourke attended the event, along with Petit and Roman Polanski, who was slated to direct whatever project emerged from the meeting.

This evening remains legendary in Pink Floyd lore for several reasons: Nureyev’s beautiful home and matchless collection of decorative arts, the lavish outlay of wine and food, a lack of planning for the proposed project, and the very non-heterosexual character of the evening’s activities. (“Didn’t you smell a rat?” Mason asked Waters later. His reply: “I smelt a few poofs.”)

The whole experience, which ended just before the release of Dark Side of the Moon, led the group away from the higher arts.

The Soft Machine

When Peter Jenner and Andrew King got Syd Barrett into the studio to record his first solo album, The Madcap Laughs, they needed musicians to back him up. The full Floyd was out of the question, of course, although David Gilmour and Roger Waters tried to help out by taking over the production from Malcolm Jones halfway through the process. Eventually it was decided to bring in some members of the Soft Machine.

The Softs, like Barrett (and Dave Gilmour) hailed from Cambridge and were the second most popular psychedelic band in the late ‘66 and early ’67 London scene. They and the Floyd were huge favorites among the London underground and at UFO. Their love of whimsy and free jazz, as well as the ability to play at hurricane-force rhythms, put them at the forefront of a progressive rock movement that seemed, at the time, limitless.

The band’s early 1967 single “Love Makes Sweet Music” is among the greatest British rock songs of the era, blending the spacey rush of psychedelia with a solid rock backbeat. Despite its failure on the charts, this 45 helped establish the Softs’ credentials.

Drummer Robert Wyatt was a star singer and whirlwind behind the kit; keyboardist Mike Ratledge combined jazz introspection and a sense of anarchy. Bassist Kevin Ayers and guitarist Daevid Allen were suitably gnomish characters, the former blessed with pop-star looks and a gift for melody, the latter a truly far-out character who, after leaving the group, set up the hippie collective band Gong.

By 1969 both Ayers and Allen were gone and the band, like Pink Floyd, had abandoned all pretense of pop, moving full-on into a bookish fusion of jazz and rock.

The free, rhythmically shifting Softs—perhaps the most advanced jazz-rock group in England—still had a hard time dealing with Syd Barrett in 1969–70. The group struggled just to understand the guitarist’s directions in the studio, much less back him up competently. Eventually, David Gilmour decided to have Barrett lay down tracks and have the Soft Machine play over them later.

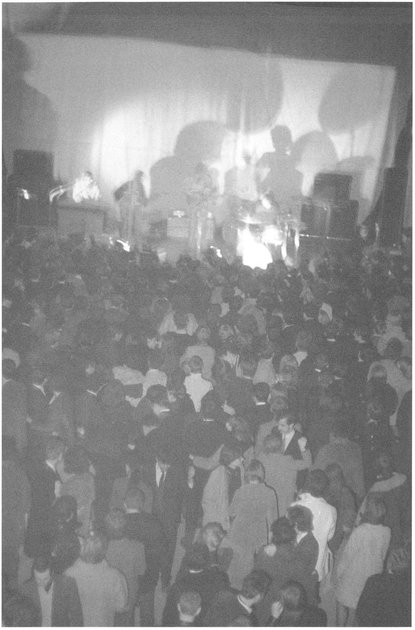

The Pink Floyd entertains at the International Times newspaper’s “All Night Rave” launch party at London’s Roundhouse, October 15, 1966. By this time, pop celebrities like Paul McCartney, and Pete Townshend—and the cream of London’s underground and “beautiful people” contingent—were picking up the nascent band’s vibrations.

Photo by Adam Ritchie/Redferns

Even Kevin Ayers, the Softs’ onetime guitarist (and an utterly loony psychedelic figure) couldn’t clock Barrett’s weirdness, although he wrote the charming fable “Clarence in Wonderland” as a tribute to Syd.

The two bands continued to interact over the years. Robert Wyatt fell from a window on July 1, 1973 and suffered a broken back. The Floyd played two benefit shows to raise money for him that November.

Mason would produce Wyatt’s 1974 album Rock Bottom and later appear with him on Top of the Pops, sitting behind the drum kit for a lip-synch of Wyatt’s surprise hit single “I’m a Believer.” Years later, Wyatt sang on the Floyd drummer’s first solo project, Fictitious Sports.

Wyatt has enjoyed a successful solo career, becoming almost a father figure to various contemporary folk and world artists. He curated the 2001 Meltdown music festival, and sang “Comfortably Numb” during Gilmour’s performance.

Pete Townshend

By early 1966 the Who was one of the most talked-about pop groups in Britain for its auto-destructive tendencies, pop art motifs, explosive onstage energy—and for Pete Townshend’s songwriting.

The Pink Floyd were nothing like the Who, but that didn’t stop Townshend—in a phase during which he embraced the rock underground—from checking out the band at UFO. A tripping Townshend, viewing the elongated visage of Roger Waters, confided to a friend that he feared that the Floyd’s bassist might swallow him alive.

The Who’s mouthpiece was never afraid to express strong opinions about others’ work to the press, famously running down the Beatles’ “Strawberry Fields Forever” as well as Piper, which he felt was so dissimilar to the group’s live show as to be bubblegum. (This from a man whose band’s big 1968 single release was the trivial “Dogs.”)

Both bands, or at least the leaders of both bands, were searching for ways out of the normal pop paradigm. While Townshend wasn’t the first to do a true “rock opera”—the Pretty Things, recording with Norman Smith at Abbey Road in 1967, beat him to it with S.F. Sorrow—he was the first one to have a hit with the concept in 1969 with Tommy.

In the intervening years, the Who would engage successfully (Quadrophenia) and unsuccessfully (Lifehouse) with the dreaded “concept album,” but Floyd really perfected the formula sonically and lyrically with 1973’s Dark Side of the Moon.

While Townshend became friendly with the members of the Floyd, any hope of a long-term friendship between Roger Daltrey and the band was laid to rest when the Who’s singer mistook Rick Wright for Eric Clapton at a party.

Gilmour, always more interested in working with other musicians than were the other members of the Floyd, formed a friendship with Townshend in the 1980s.

The Who’s guitarist penned lyrics for two Gilmour tracks from 1984’s About Face album (“All Lovers Are Deranged” and “Love on the Air”); the two then cowrote the anthemic “White City Fighting”—originally submitted to Gilmour but rejected because he couldn’t relate to the lyric—and “Give Blood” for Townshend’s 1985 White City: A Novel.

Gilmour also played lead guitar in Townshend’s Deep End band the next year, ultimately appearing on the group’s live video and CD.

When the Floyd were inducted into the U.K. Music Hall of Fame on November 16, 2005, Townshend, a peer, contemporary, and supporter, was a logical choice to introduce the band. (Only Gilmour and Mason attended, as Waters was in Rome and Wright was in the hospital having surgery.)