Tree Divination:

The Ogam

When it comes to certain magical practices, I am of the opinion that if it isn’t broken, don’t fix it. The ogam or ogham (pronounced oh-wam) has erroneously been attributed as an ancient Celtic system of divination—when, in fact, it is no such thing. Irish mythology informs us that the ogam was created by the god Ogma and consists of twenty basic letters formed as notches upon a crossbar. A further five letters were added later to account for foreign words borrowed into the Celtic languages. 87 The following exploration will focus only on the original twenty letters of the ogam system.

The ogam as a divinatory tool was invented or created by the twentieth- century writer Robert Graves in his highly influential book The White Goddess. Although a greatly admired piece of work and essential reading to the modern Pagan, it is safe to deduce that Mr. Graves came to some rather incorrect conclusions, the ogam being one of them. But something rather magical happened—however incorrect the belief that this system of divination is ancient, it has become a colorful and appropriate system for modern Pagan practice. The ogam did exist, as the inscribed stones of Britain and Ireland proclaim, and although preserved mostly by the Irish Celts, there is evidence that the ogam was used in the British Isles. The majority of surviving stone inscriptions date from between the fourth and eighth centuries of the Common Era.

There may be little evidence to suggest its use as a divinatory tool, but it was undeniably a system of writing that was culturally specific predominantly to the Irish Celts. Epigraphic examples on stones and wood suggest a commemorative function and a manner by which coded messages could be effectively and covertly disseminated. The fourteenth-century manuscript the Book of Ballymote contains over ninety examples of ogam usage, of which a peculiar mandala-type sigil known as “Fionn’s window” is of particular interest to modern Pagans. It places the four aicme, or family groups of the ogam, within five concentric circles that radiate out from the central circle to form four distinct paths along a cardinal circuit. While the function of Fionn’s window may be lost to us, according to ogam authors Mark Graham and Heather Buchan, it has been adopted into current practice to symbolize the wheel of life and the stages for the evolutionary journey of the human soul. 88 From this aspect a modern divinatory function has evolved.

Symbols are powerful allies in themselves, and the continuous development and usage of the ogam from its misty past through its resurrection in the twentieth century is indicative of its ability to inspire and spark the human imagination. I have a rather straightforward attitude to the ogam in that I like it; I think it’s a valuable tool that has had some bad press, mostly due to Mr. Graves and his musings. I have heard many claim that it should not be used as it is not genuinely Celtic. Its divinatory aspect may be recently invented, but that does not negate its value or power. It still has presence, and it does connect us to the lands and the culture of the Celts. We must remember, too, that the Celts were not a group of people that existed only in the distant past, and that for anything to have validity it must come from the past and be of the past. The Celts survive; we are still here, continuously making this spirituality relevant and applicable to a modern world.

Systems of divination are only as effective as the magician’s connection to the tool, therefore an understanding, symbiotic relationship with the primary trees of the ogam system will work in a divinatory sense. Using that methodology, one could easily attribute symbols to the trees and shrubs listed in “The Battle of the Trees” and use them as casting tools for divination—there would be absolutely nothing wrong with that, and I would hazard a guess that it would be rather effective. But when it comes to the ogam, the majority feel somewhat put off by its assumed complexity, when in actuality it is not in any form complicated or difficult. As with most things in life, there is a knack to using it effectively, and I aim to share that with you here.

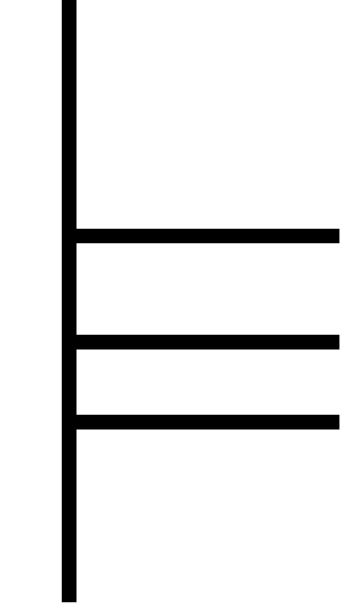

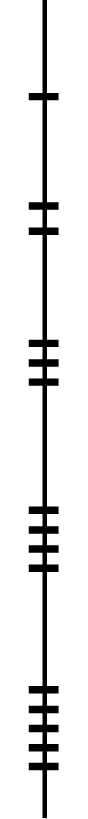

Traditionally the ogam is composed of slivers of wood, preferably taken from each individual tree and fashioned into “staves,” little short sticks no longer than around 2 or 3 inches in length and ½ to 1 cm wide. A symbol is then etched onto the stave to represent the individual tree; for example, the ogam stave for alder (fearn) would be represented as:

A number of these are then randomly selected from a bag or box and cast onto a reading surface. In the several workshops I have given on ogam divination, the first complaint I hear is the fact that folks do not know what to cast them onto or how to read the staves in a manner that brings meaning to the reading, i.e., the position or pattern they form upon casting. Chapter 29 of this book will provide you with a glyph upon which to cast your ogam staves (and any other form of divinatory tool); this offers a point of reference in conjunction with Celtic myth by which to read the tool against.

Normally books present the ogam as a complete list of twenty trees, with the ogam stave symbol alongside it; these consist of lines etched to the left, right, directly across, or diagonally traversing a central column. Then one is presented with the English name, Celtic name, and their quality. All in all, most people take one look and think, “Well, that’s bloody complicated!” and promptly abandon it. Like most things in life, there is an easy way and a difficult way.

First and foremost, it is essential to note that the ogam is split into four aicme, which roughly translates as “family, clan or tribe” and is pronounced “AYKH-muh.” Each aicme is subdivided into a group of five trees, all sharing a commonality within that grouping. To each group I assign a quality that is indicative of the journey upon the Tree of Life and encapsulates the function of each group, which I list thus:

- the branch of beginning

- the branch of gaining wisdom

- the branch of introspection

- the branch of transformation

The separate aicme are identified by the Celtic name of the first tree within that grouping; for example, the first tree of the first aicme is birch (beith), therefore this group is called aicme beith.

Faced with twenty bizarre and alien sigils on a stick and a multitude of trees to remember in order is difficult for most people, so the easiest way is to avoid looking at it as a sequence of twenty trees and focus instead on them being four groups. Five trees are far easier to digest than twenty. See the glossary for pronunciation of the Celtic names.

The branch of beginning, Aicme Beith, is grouped thus:

|

english name |

celtic name |

mnemonic |

quality |

symbol |

|

birch |

beith |

birch |

vitality, beginning |

|

|

rowan |

luis |

ran |

quickening, insight |

|

|

alder |

fearn |

away |

foundation |

|

|

willow |

saille |

with |

intuition |

|

|

ash |

nuinn |

ash |

rebirth, peace |

Look at the tree list. They have something in common: they are mostly colonizing trees—they prepare the ground for new growth and future woodlands. They are the trees of beginning; they pave the way for future generations. On a spiritual or divinatory level, these are the trees that embody our quest, the journey through life and into the spirit. The qualities needed for life are imbued within these trees; to find them in a reading implies innocence, vitality, and the qualities required to create a firm foundation for the future. Focus on the first five trees until you are deeply familiar with them. By proxy of studying this system, you will naturally be drawn to study and observe these particular trees. Relationship will ensue; it is this relationship and the attributions of the trees that you will utilize in divination.

Mnemonics—where the first letter of the English names are replaced with something that will jog the memory into recalling the sequence of trees—will aid memory. A tip: the sillier and more nonsensical the mnemonic, the more it will stick in your mind. The mnemonic provided here is birch ran away with ash.

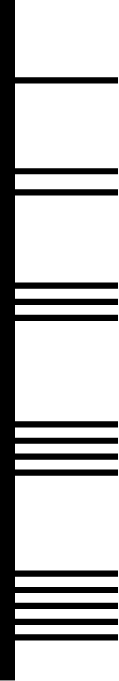

The branch of gaining wisdom, aicme huath, is grouped thus:

|

english name |

celtic name |

mnemonic |

quality |

symbol |

|

hawthorn |

huath |

hawthorn |

challenge |

|

|

oak |

duir |

or |

endurance |

|

|

holly |

tinne |

holly |

balance |

|

|

hazel |

coll |

have |

creativity |

|

|

apple |

quert |

appeal |

beauty, eternity |

The foundation has been set: the land prepared and made ready for new growth, new species, and new experiences. The five trees of this aicme are the trees of wisdom. They represent our expressive qualities and the setting of new patterns. On a psychological level they express our coping mechanisms and our ability to deal with the human condition. The patterns laid down by the first aicme influence these trees; they are a continuation of the previous qualities. The first steps towards maturity require us to adequately access our own inner strength and creativity, to be functional, well-balanced individuals. This may be hampered or influenced by the functions of the first aicme. Focus on the five trees until you are deeply familiar with them. How do you glean meaning from these attributions, and what other qualities would you place on these trees?

The mnemonic of this aicme is hawthorn or holly have appeal.

The branch of introspection, aicme muin, is grouped thus:

|

english name |

celtic name |

mnemonic |

quality |

symbol |

|

bramble |

muin |

bramble |

looking within |

|

|

ivy |

gort |

is |

development |

|

|

reed (broom) |

ngetal |

ready |

harmony |

|

|

blackthorn |

straif |

but |

control, coercion |

|

|

elder |

ruis |

elderly |

change |

These are the trees that epitomize our search for meaning, for looking deep within to the place of mystery. They express our desire to fill the void—the deep emptiness that may afflict individuals as they approach the midpoint of life. Our lives may have fallen into repetitive patterns of behavior, secure in our insecurity. The bramble sends out a long, spiky shoot; unaware of where that arching will take her, she leaps, knowing deep down that her arch will touch firm ground and take root. We may long for the sense of being rooted to home, work, lifestyle, spirituality, or tradition. Our attempts to control our own fates and fortunes may lead to inappropriate action—we may long for change while simultaneously fearing it. Reed, or broom, teaches us to live in harmony with our environment, while the danger of blackthorn is its surreptitious attempts to gain control over any given situation, sometimes to its detriment.

What do these five trees tell you? Watch them and the manner in which they interact with their environment. These are trees steeped in lore and legend; seek them out.

The mnemonic for this aicme could be something along these lines: bramble is ready but elderly.

You will note that this, along with the other mnemonic, contains the actual names of the trees themselves to jog your memory. Play with words, like the above “elderly” that hides the word elder within it.

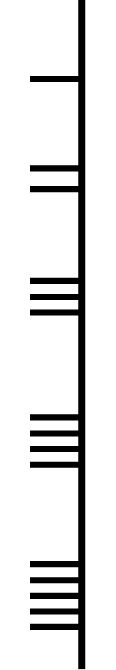

The Branch of Transformation, Aicme Ailm, is grouped thus:

|

english |

celtic name |

mnemonic |

quality |

symbol |

|

pine |

ailm |

perfect |

objectivity |

|

|

gorse |

onn |

groves |

wisdom, synthesis |

|

|

heather |

ur |

have |

gateway, passion |

|

|

poplar |

eadad |

popular |

overcoming, insight |

|

|

yew |

idad |

yews |

death, immortality |

This is the aicme of acceptance, of coming into being, of being comfortable within your own skin—yet it is as challenging and complex as the previous aicme. On a psychological and spiritual level these trees teach us about the mysteries of being and transformation. We learn to stop fighting and stand in our own power; it is the power of acceptance, of being who we are and who we want to be in this experience. On the surface of things it seems that this aicme leads only to death; however, the nature and message of yew is quite the contrary, for they truly may be immortal. Death is merely a midpoint in existence, and these trees lead us to this understanding. In the journey of life we become elders, experienced; we learn to watch and listen before responding and utilizing our wisdom of the journey to help others on theirs.

Study these trees and learn their mysteries. What other qualities can you add to their attributions?

The mnemonic for the aicme could be composed thus: perfect groves have popular yews.

ª ª ª

So there we have it: a snapshot of the window of ogam. Used alone, it can seem cumbersome and messy; used in conjunction with other methods, it bursts into life. Before you attempt to use the trees in a divinatory sense, get to know them—create your own set of staves, try not to jump ahead, focus on one aicme at a time; the others will come in due course. The qualities provided are keywords—they serve only to jog your memory; further meaning can be gleaned from research and connection to the trees. Get out there and find the trees, move into relationship with them, and decorate your understanding of the trees’ divinatory qualities by proxy of relationship.

I suggest that, when casting, you use no more than nine staves at a time. When creating your staves, fork the bottom end of the symbol with two prongs so that you can immediately identify if the stave is upright or not. If you really can’t get your head around the symbols, there is absolutely nothing wrong in writing the name of the tree on the reverse side of the stave.

ª ª ª

And so we depart from the shades of the forest and cast our eyes closer to the ground, to our companions in the plant kingdom.