Staddle stones like this one were once used as supports to raise granaries off the ground to protect them from rats and other pests. Such an ornament fits my criterion of garden art being largely utilitarian.

THE GARDEN AT BRANDYWINE COTTAGE WAS NOT created in a month or even in the first year or two. While I knew I could make a wonderful garden on that appealing piece of land, it did not come to me all at once. I had created several other gardens in my adult life, and I knew it would take years to make the garden of my dreams a reality. I also knew it would end up being different from the dreams, because reality is less forgiving and dreams change over time. Even if I had been able to conjure up a complete picture immediately, I still would have wanted to take the time to let it unfold, and to do the work myself.

A garden like ours, in which there are layers of interest in every month of the year—even flowers to cut for indoor arrangements—is not a common achievement in the temperate climate (USDA zone 6) of my region, where freezing temperatures keep most gardeners indoors from November through March. More common in that area are what I call “big bang” gardens, which feature extravagant floral displays that begin in the spring and wane in midsummer. By then gardeners often feel as burned out as their plants, and might even be praying for an early frost so they can be done with it until the next spring.

For Michael and me, frost simply means the start of another gardening season. It is a slower season, for sure, a time for a final cleanup of the borders, dealing with hardscape problems, doing necessary pruning and other chores that we failed to get to during the garden’s peak seasons. Even with snow on the ground, we can be cleaning and sharpening tools and getting the shed organized, which is more than just busywork. Working during the usual gardener’s downtime makes everything go more smoothly when the rush of outdoor chores arrives—a rush that begins for us when the winter layer of the garden begins to pop in February, months earlier than the usual April start time for most of our gardening neighbors.

Since we never really stop working, sometimes I am not even sure which garden season I am tending. Take my crocuses and snowdrops, for instance: in March, Crocus tommasinianus might be blooming with Galanthus elwesii; in fall the combination might be Crocus pulchellus and Galanthus ‘Potter’s Prelude’. So the question is, are those spring crocuses and snowdrops the first of the year to bloom in my garden, or the last? I do not have an answer to that chicken-egg question, but since our gardening year never ends, it really does not matter. Our garden is a living-growing-dying art form, always unfolding, always changing—an unfinished rhapsody that we continue to edit and refine as the seasons come and go, as plants grow and die, and as new ideas and obsessions are added to the mix.

top and bottom: We see this view of the hillside every day when we go in and out of the house, so the combinations need to be both pleasing and change with the seasons. The two photographs were taken in early spring about three weeks apart.

The key to creating a many-layered garden is understanding and taking advantage of the ways plants grow and change through the seasons and over the years, providing different textures, colors, and effects and evoking a variety of feelings. Garden layers are made up of a variety of plants, some with complementary or contrasting colors, others with interesting shapes or textures. Layers are more than just perennials, or annuals, or bulbs, or groundcovers—they are more than just the ground layer of plants that is the sole focus of many gardeners. Beautiful combinations are certainly possible, even on the tiniest scale: dwarf Solomon’s seal underplanted with moss certainly makes a precious 6-inch-high picture. But to get the most interest from any garden, all the layers need to be considered, from the ground level to the middle level of shrubs, and small trees up to the canopy trees. Growing plants on vertical surfaces—walls, fences, trellises, arbors, and other supports, even climbing up trees when we can be sure they will do no harm—adds to the picture by bringing flowers and foliage to eye level and above.

I also consider entire beds, or even entire garden sections, as layers unto themselves. My hillside, which looks like a tilted canvas when viewed from below, could be considered a layer, while the flat area around the house is another layer. These areas in turn are divided into smaller and smaller spaces, right down to the level of three-plant combinations—as when I underplant witch hazel (Hamamelis ×intermedia ‘Pallida’) with a yellow Galanthus cultivar and winter aconite (Eranthis hyemalis), with the yellow of the witch hazel flowers reflected in the plants on the ground.

Our garden at Brandywine Cottage has been designed so that different areas peak at different times: For example, when the hillside is at its height of bloom in early spring, the borders below are barely breaking dormancy, and when the borders peak later in spring, the hillside has entered a quieter phase. Most areas have more than one peak. The hillside puts on a second show when hydrangeas bloom, and a third show with colorful fall foliage; the ruin wall goes through several waves of bloom; and the borders offer a series of waves that carry on until frost.

I would not be happy with a garden in which everything bloomed at once. From a gardener’s point of view, I would have little motivation to do any work once that peak had passed. And from a design point of view, it would be like listening to a cacophony rather than a symphony—which, like my garden, has its crescendos, its quiet spaces, and its movements, all carefully composed. Each section has multiple layers of interest, sometimes working in concert and at other times playing off each other. It is the gradual, suspenseful revelation of the composition—the hallmark of any good piece of art—that I find most exciting. The only difference is that the occasional mournful adagios in a garden are never planned, only dealt with in the aftermath, and often sadder than any music can be.

If my garden is a symphony, I hope I have made it a romantic one. I want my garden to seduce me, to draw me in, to make me forget about the rest of the world as long as it holds me under its spell. Even though I have no children, I understand why my grandmother expressed such pleasure whenever she had all the family around. I like to have all my plants around, to be surrounded and embraced by those I love.

One other garden layer—or maybe garden player is a better term—is the passage of time. After twenty years spent gardening the same space, it seems that times does go by faster now, maybe because I am always pushing the seasons, always looking ahead to the next thing. When I started the garden, I was so anxious to see things come into bloom that I always picked the earliest blooming cultivars. Now, as I am growing older along with the garden, I have learned the rewards of stretching out each season as far as I can, by adding the late bloomers of a genus to the mix. I started with an early rhododendron, Rhododendron mucronulatum, and now I plant late-blooming native azaleas. To my plantings of early cyclamineus types of narcissus, I have added later blooming jonquils. As I savor the fullness each season has to offer, I think of my mother’s advice whenever I gobbled my food as a child. “Slow down,” she told me. “Enjoy it!”

All these layers of plants, viewed in real time and as time passes, make the garden interesting, and provide us with seemingly endless challenges and surprises. Sometimes we plan our combinations and layers, and they work, but serendipity also plays a role, and teaches us what plants we might throw together more purposefully next year. Sometimes the most memorable garden moments are the most fleeting, as when a single leaf, backlit by the sun, is transformed from opaque to a translucent tracery of veins more beautiful than any stained glass. I hate to leave my garden for any length of time because it means I miss these moments, or the more predictable blooms of favorite plants. It is no consolation to remember that I may have seen these same plants in bloom many times before, and that such transcendent moments are out in the garden every day, if we only pay attention.

This June view, looking into the ruin garden from the deck above, shows how every layer is used, from the ground-hugging plants to the taller plants to those growing in the wall, on to the trees and shrubs behind the wall. The ruin garden was created in the ruins of the barn’s stable on the property.

One way I try to make the seasons last longer is by extending the bloom time of favorite plants. I have expanded my collection of narcissus to include both early and late blooming varieties, such as (left) Narcissus cyclamineus, shown in late March, and (right) N. ‘Pipit’ in late April.

This late April view, looking over the formal hellebore bed to the hillside, shows how the sections of the garden play off and with each other, and how the entire garden works together to create a symphony of color and texture.

My first attempt at designing the north border (inset) was not offensive, it was something worse: dull. Twenty years later, you can see the difference, in color choices and other aesthetic characteristics.

In my classes at Longwood Gardens and in my advice to garden design clients, I stress the importance of making a plan, but not necessarily following it to the letter.

If you have a dream for a space, a plan can help solidify that dream and make vague ideas more concrete, but it should not make your ideas as immoveable as concrete. A plan can serve as an outline, but once you make it, put it in a drawer. The only exception might be the hardscape, such as a formal patio, which can sometimes become a weak point in a garden if it is not carefully designed and constructed. But when dealing with plants, it is best to consider a garden as living sculpture—always in flux and, if we learn to pay attention, always teaching us what it wants to become.

A plan made in one particular moment in time and rigidly followed will satisfy neither the gardener’s creativity nor the garden’s full potential. If clients force me to commit my ideas to paper, I tell them, “This is only an idea, a sketch.” I do not want to hear from them a year down the road, when I change my ideas: “But the plan says you were going to put a yucca here!” That is not following the creative impulses of the moment; that is gardening by numbers.

I have similar advice when it comes to rules. Some gardeners get so hung up on all the “rules” that have been laid down by so many “experts” that they are constantly wondering, “What am I doing wrong?” My first rule for designing a garden is that there are no rules, at least none that everyone must follow. In any creative endeavor, rules help to show us what has worked before, but as we gain more experience, the rules can be put in the same drawer as our plans. You might even find that knowingly breaking the rules can be fun, once you realize that the taste police are not going to knock on the door and drag you away for doing this. The only punishment might be a few raised eyebrows from the primly rule-bound, but these reactions alone sometimes make rule-breaking worthwhile. As in any pursuit, stretching and bending and breaking rules can get out of control. But it is within that tension that gardeners (and any artists) do their work—trying to maintain the balance between too light a touch and being ham-handed, the straight lines and the playfulness.

The bottom line is that a garden should be fun. If plants and gardening are things you are obsessed with, as I am, having fun certainly helps pass all the hours devoted to them. Why spend all this time if we are only following someone else’s rules? Experiment, play with colors, do what pleases you, and do not be afraid to change things if you wish. In your own garden, you are the director; you have the ultimate say. Of course, there is much to learn from other gardens and gardeners, from magazines and TV shows and, I hope, even from books like this one. But take what you learn and make it your own. I have run with that idea for more than twenty years, and I plan to continue.

There have been so many “rules” about color in gardening—which ones go well together and which ones do not, which ones are in and which ones are out—that trying to make sense of them all would make a muddle out of anyone’s color sense. Rules about color certainly provide guidance, and even prevent anarchy in some cases, but what does it matter if we have a little anarchy in our gardens? We are not talking about riots in the street. As messy as it might be, the only thing hurt by a riot of color is an oversensitive eye. Making messes just might be an integral part of the creative process: think of all the great cooks who started out making mud pies. They tried to eat them, spit them out, and kept on trying until they got it right. Sometimes the way we learn best is by following our impulses, and then sorting out the resulting messes by ourselves.

One fall when I was still in grammar school, I talked my mother into letting me buy tulip bulbs for our garden. I chose every color they had in the store and planted the bulbs like soldiers marching single file, thinking it would be quite elegant to line the walkway and driveway like that. This was not two dozen tulips—I was doing obsessively large plantings even then—and when they came up the next spring, of course everyone commented on how beautiful they were. I will never know if those people were just being kind to a kid, or if they really did not see what I saw, because even at that young age I knew something was not right. The flowers reminded me of the jumble of candy colors in my Easter basket—great if you are a boy with a sweet tooth, but not so great, I realized, for a garden.

This tulip planting was my first lesson in design, and though I surely could not have put it into words back then, “lack of unity” comes to my mind now. As I recall, the following fall I planted tulips again, and this time they were all one color. They still might have soldiered down the driveway, but eventually I learned that lesson, too—that they would look more natural in clumps and drifts. And today, instead of being daunted by tulips (as I might have, if the color police had arrested me after the tulip incident), I plant them all over my garden.

Combining unusual plants, as in this match between the flower of Trillium luteum and the golden leaves of a Convallaria cultivar, is more than good design. It makes people think. The most frequent comment I hear about this combination is, “What are those plants?”

Taking a cue from the white flowering dogwoods and white color of the cottage, we added the white tulips to bring the color down to ground level in a controlled way.

Repeating colors across borders (here, from the west border of the vegetable garden into the north border) helps unify the garden. In spring, I like to work primarily in pastels, which look particularly pleasing in the angular, pristine light of this season.

Another childhood memory: Grandmother Culp had a narrow border beside her house in Florida, and one year when I was visiting, I noticed she had planted flowers that were bronzy brown, yellow, orange, and peachy—odd sunset colors. I am certain this combination was not in vogue, but she was following her own vision, and a vision of this richly hued bed stayed with me—perhaps traumatized me—for years. “What a weird lady my grandmother is,” I thought. “Nobody else I know uses colors like this in their gardens.”

Psychologists understand that stimuli from when we are young, like being baffled by a grandmother’s color choices, can trigger responses many years later. Now I use these colors in my garden, and where did that idea come from? It did not just pop into my head, and I do not remember reading anywhere that this was trendy. In many cases I do give myself permission to push the limits, buck the trends, break the rules—but maybe in this case I was simply remembering and recreating what my grandmother did so many years ago. A moral of this story might be that there really is nothing new in horticulture, just new gardening grandsons to rediscover everything their grandmothers did.

My one rule about color is that you should do what you like; that way you are assured of pleasing at least one person in this world. Take the rest of what anyone says as guidelines, and let your own eyes be the judge. If you do not like the combinations shown in the pictures in this book, I will not be insulted. And if you do like them, feel free to claim them as your own. I am all about sharing.

When I started this garden, I did not follow this advice. In early years I did not even use any yellow. Less experienced and more impressionable, I had bought into the pinky-blue palette so fashionable back in the 1980s. Fast-forward a few years, and with my confidence ratcheted up a few notches, I realized that this was my garden, to do with as I pleased. If I liked a particular color, no matter how gaudy or outré, then it was my job to make it work. Yes, using some colors can be a challenge. Orange is one, because of its attention-getting brightness—there is a reason that traffic cones, safety vests, and life preservers are this color. But just as there are no bad plants, no color is intrinsically bad. It needs to be considered in context, in juxtaposition with other colors.

I remember attending a lecture at which a well-known gardener stated that you should never use yellow and pink together. This did not sound right to me—I thought immediately of all the pink flowers that have yellow anthers—so I went out in my garden and proved this speaker wrong. I combined pink roses with yellow honeysuckle on the pillars in my rose bed, and pink phlox and yellow black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta) in my border—and both combinations stood up well under the bright midsummer light. The amount of light or shade in which a particular combination is viewed, which also can change with the time of day and the season, has a definite impact on how it may look to your eye. For me, the same pink and yellow combination that looks wonderful in summer might need brighter colored companions in the lower, slanting light of spring or fall, to make it really pop.

One of the joys of a layered garden is that it allows for flexibility, letting me change the predominant colors in a bed several times during the season: white, along with yellow and pastels, in spring; hot colors such as acid yellow, purple, red, and orange in summer; and warm colors such as creamy yellow, apricot, and burgundy in fall. To me, such changes are what make a garden exciting. If my garden were a book, these changes would make me want to keep turning the pages, keep looking.

Color-themed gardens do not need to be all of the same color exclusively. For example, a white garden will look better with blue flowers as an accent, rather than bluish-whites or yellowish whites, which in this context can look dirty or unflattering. Another color accent can enhance the values of the featured color (or provide a contrast, if that is your wish). White heightens the color of any other color it is placed beside. For a different effect, purple, bronze, and some shades of gray soften any brighter colors next to them. When in doubt, I add blue, which works with both hot colors and cooler pastels.

Many people are initially drawn to gardening by the colors of flowers—I know I was. But over many years of designing with plants, I have come to believe that the shape of plants, more than their colors, is what gives any garden its drama and punch. Try taking a photograph of your garden, edit out the color, and see how interesting this picture is. If you can make out distinct shapes and textures (texture being the surface quality of a shape), then you have probably gotten this right. If everything in your picture seems to blend together, it may be time to invite some bolder plants to your garden party.

My garden’s signature shape is provided by upstanding plants and man-made elements with vertical profiles. Since the predominant orientation of the garden is horizontal, these verticals—by piercing that horizontal plane—stand out, connect the earth to the sky, and help carry the eye from space to space when repeated throughout the garden. The rose pillars, bamboo teepees, and even the pointed pickets of the vegetable garden fence provide year-round vertical interest, while our selection of upright plants changes with the seasons. Taking the north border as an example, springtime verticality is provided by the flowers of Digitalis species, Salvia nemorosa ‘Caradonna’, and Stachys macrantha ‘Superba’, to name a few; in the summer, specimens of Kniphofia, Acanthus, and Thermopsis; and in fall, Leonotis, Canna, and Agastache selections. In all three seasons, Phormium specimens in containers add verticality to the same border.

While some vertical plants end up towering over human beings, the key is not their sheer size but the contrasts among the plants in a specific grouping or bed. On a smaller scale, the strappy, pointed leaves of irises can provide vertical interest after the flowers have bloomed. The same can be said for various ferns poking through a woodland garden composed mostly of groundcovers. Even the flower stalk of bolting lettuce can be a vertical accent in the vegetable garden (at least until Michael cannot stand it anymore and rips it out).

The trees that cover more than half the property gave me the cue for the use of verticals in the borders. The combinations I like best intermingle interesting shapes and textures as well as colors.

Having a signature shape is as important as having a signature color. I like vertical shapes, for the sense of drama they impart to my garden.

Some people do not like using umbels in their gardens, since many weeds (such as Queen Anne’s lace) have flowers of this type, but I like using plants like this Angelica gigas for just that natural feeling. They also provide horizontal elements that work well with adjacent verticals. The places where these vertical and horizontal planes intersect are where the excitement happens in a garden.

I am not a hosta collector, but I find the genus Hosta’s variety of leaf shapes and colors to be important design elements in my shady borders.

I like Acanthus spinosus for its unusual vertical flower spikes, and because it does well in dry conditions.

Shapes and textures are especially useful in punching up the interest in a shade garden, where any plants that flower tend to be subtler than their sun-loving counterparts. There is a wealth of shade plants with bold-shaped leaves, like hostas and hellebores, as well as many lacy-leaved plants, such as ferns. The challenge is to find vertical and finer grass-like shapes to add to these combinations. Many species of the shade-loving genus Carex fit both these bills, providing grassy texture and upright interest. Natives like C. pensylvanica, C. plantaginea, and C. flaccosperma, make themselves even more useful by thriving in dry situations once they are established. The pleated leaves of C. plantaginea can provide added texture to plantings. It is also semievergreen, which extends its season of interest and, as with all evergreen plants, makes it a great foil for ephemeral flowers. Both C. flaccosperma and C. laxiculmis ‘Bunny Blue’ offer a glaucous, gray-blue color note that tends to lighten up areas of deep shade, and provide a contrast or complement to other plants in the garden.

Selections of Hakonechloa macra offer shade gardeners grassy foliage in a range of bright colors. ‘Aureola’, with a graceful texture and arching mounded habit, is beautiful as a specimen or in drifts. Both ‘Aureomarginata’, with its yellow variegation, and ‘All Gold’ will light up a shady area; these two cultivars work well with other yellow or yellow-variegated shade plants. ‘Albovariegata’ is a good companion for plants with white or cream variegations. Recent introductions such as ‘Nicolas’, ‘Beni Kaze’, and ‘Naomi’ have green leaves that turn red in fall, offering another color to brighten up the shade. I especially like ‘Beni Kaze’ (Japanese for red wind) because its red coloration appears earlier than the other two. Even the dark green foliage of the straight species, H. macra, is compelling, if in a more serene and understated way.

I also love the strappy evergreen (really ever-purple) foliage of Ophiopogon planiscapus ‘Nigrescens’, which seems to mimic the patterns of light and shadow on the forest floor. Every year I find more uses for its deep-purple, near black color, which is an elegant addition to many combinations in the shade. We use many potted Agave specimens as accents in the sunny parts of the garden, their spiny leaves arching out from the center like so many synchronized divers leaping from a single point. Selections of Sempervivum can be architectural in a similar way, if on a much smaller scale. Other shapes I use throughout the garden include the bubble shape of flowers like alliums, and the chalice shape of hellebores and magnolias. With all these plants, a single specimen will stick out like a sore thumb, so I try to use many specimens, often spread through several beds.

When parts of the garden start to get loose and blowsy in the summer months, I like to beef up this layer by adding cannas and bananas. Anyone who has grown these tropical plants knows that the flowers are secondary; what they provide is the bold shape of their large, glossy leaves and a dramatic upright accent that will carry through until frost cuts them down, by which time they are among the last sentinels in the garden.

Our garden does not have the luxury of distinct areas—separated from each by other walls, hedges, or other visual barriers—which can be as different as night and day. Except for the ruin garden, which was created in the ruins of a stable next to the barn on the property, each of our beds and borders can be viewed from many others, so I have tried to make them all relate to one another even while giving each its own character. My goal has been to create a series of garden rooms without walls in which the transitions between the different areas, rather than feeling abrupt and jarring, meld more or less seamlessly together.

One key to creating unity in a garden full of diversity is repetition. I repeat plants in different beds, sometimes the same plants and other times different species of the same genus. I repeat colors across garden areas, as well as vertical accents and other shapes and textures. Each season can have a predominant color, or a genus that takes center stage, which is an easy way to unify different areas. The straight edges of the borders of our garden are appropriate for the age of the house, but these neat lines also provide continuity and definition to our otherwise ebullient planting style. Another repeating element that ties the various garden areas together is the paths and walls, which are composed of similarly colored stone and gravel, as well as grass.

I use Crocus tommasinianus not only for its colorful blooms (shown on the hillside in February), but also because it naturalizes freely.

I use many forms of corydalis in my garden, including the soft rose-red Corydalis solida ‘George Baker’ and the yellow-flowered C. cheilanthifolia. The latter plant sows itself into crevices of the stone walls. Before it blooms, its foliage is often mistaken for a diminutive fern.

As various self-sowing species of Corydalis, Thalictrum, Rudbeckia, Dicentra, Stylophorum, Crocus, and Chionodoxa spread themselves throughout the garden, they loosen up the design, naturalize and soften the space, and make the garden look like it has a mind of its own, which, of course, it does. A garden can be akin to theater, but there can also be magic in the air, sleight of hand performed by a gardener who knows how to manipulate plants and point of view. If self-sowing plants make a garden look loose and happy, I try to extend this illusion to make it appear as if other plants are self-sowing as well. One way I do this is with the arrangement of hostas on the hillside. By pairing larger varieties higher up the hill with smaller ones of the same leaf color and form below—Hosta ‘Big Daddy’ with the smaller ‘Blue Cadet’, ‘Sum and Substance’ with the diminutive ‘Zounds’, H. sieboldiana with the H. ‘Mouse Ears’ series—it looks as if the larger plants are happily scattering their progeny down the hill. In this and many other ways, I see myself as the wizard behind the curtain, manipulating the scene in thought-provoking but not obvious ways, always trying to let the plants and their natural beauty speak first.

As well versed in the theoretical aspects of design as any of us might be, our ideas eventually have to be interpreted in the context of an actual garden site. We like to think of ourselves as the creators of our gardens, and in many ways this is true. But our gardens also help to make themselves by clearly showing us what will and will not thrive in the particular conditions available. Accepting these limitations can take time: How many gardeners have imagined that they have enough light to grow the sun-loving plants they love, only to finally realize, several years and many dead plants down the road, that what they really have is a shade garden? Some frustrated gardeners, faced with the inability to grow what they want, may resort to drastically altering a site to accommodate their desires.

As a collector, I need to use every trick in the book to give the garden unity. Here, the blue of Myosotis sylvatica links the beds together. Beware of overplanting forget-me-nots; one small specimen of this biennial can spread to cover a wide territory.

The ruin garden, in the beginning (top) and twenty years later (bottom): I tried to accept the property as I found it, and in the ruined stable, I immediately saw an important piece of hardscape that I wanted to celebrate and work with. The two troughs were only the lead in the novel that the ruin has become.

When I moved to Brandywine Cottage, I pretty much left the landscape as I found it, but another gardener might have clear-cut the hillside to get more sun, amended the soil with truckloads of organic matter to make it more moisture-retentive, created a waterfall and dug a pond to house water lilies and a school of colorful koi. While such landscape makeovers can work, they can be very expensive, and by altering the natural landforms they can also lead to unintended consequences. If I had made all of these alterations, chances are that the soil on the hillside would have eroded and the well, which was there and working, would have run dry. At the very least, the simple historic character of the property would have been irrevocably changed, and the wildlife the garden now harbors would have been far less diverse.

Certainly, a successful and beautiful layered garden could have been created here even if the site had been heavily altered. But Michael and I have a general philosophy of gardening that could be summed up by saying that we try to work within our means and leave a light footprint on the land. This philosophy—which extends to our minimal use of watering, fertilization, and pesticides—might seem to have little to do with the layered garden, but in fact it has everything to do with it, since it has informed all of our choices, from the particular plants we choose to the methods by which we grow them.

Rather than trying to force our own wishful thinking onto a piece of ground, I believe we can avoid much wasted time and effort by learning to garden with the site rather than against it. It is what we have tried to do: work with what we found to make a garden that looks inevitable, rather than imposed on the landscape. While this path might seem easier, because it involves no drastic interventions, in some ways it is more challenging because it demands that we carefully observe the site over time so we can learn what it has to offer. A garden might be compared to a favorite book: the more time we spend in it, the more we read between the lines, the more we can glean from it and the more delight we can experience from it. The flaw in this analogy is that authors do not rewrite their books between our readings, while gardens are always being rewritten, either by our own hands or the unseen hands of their original creator—which means we can never stop paying attention.

When I began working on the Brandywine Cottage property in February 1990, I had to spend months cleaning it up before I could even consider making a garden. As I worked my way across the acreage, I began to get a feel for the landscape. For any gardener, giving a new property time to reveal itself keeps us from doing anything that we might have to undo later, and will inform many future planting decisions. I noted how the light played across the property, through the day and over the seasons; where water collected after rainstorms and where the soil dried out first. By watching where the snow melted first, I discovered warmer spots that I knew would be possible locations for late-winter bloomers or borderline hardy plants. If you are going to garden with minimal water and fertilizer, as we do, it also is important to figure out what type of soil you have, and its pH level, before you waste money planting (and losing) a host of inappropriate plants.

I like to make color combinations at all levels of the garden. In April, at tree level, the pink flowers of Prunus ‘Okame’ combine with the new chartreuse foliage of a willow.

I found numerous black walnut trees on the property, which were an important food source for early residents but are the bane of anyone trying to garden beneath them because they affect the soil. Actaea ‘Brunette’, with unusual purple stems and foliage, is one of many plants that will tolerate this location.

Sanguinaria canadensis f. multiplex ‘Plena’, a cultivar of native bloodroot, will also grow under black walnut trees. Something this beautiful would seem difficult to grow, but I have had it in the garden for twenty years. When in bloom, it stops traffic on our garden paths.

In learning the lay of the land, I came to appreciate trees more than I ever had before. As a designer, I knew that mature trees can help a new garden look older and more established, and by providing shade they certainly make it more comfortable, especially in the summer heat. They also provide a layer of interest that most people neglect, with foliage and bark colors and textures that can be echoed and contrasted both in other trees and in the shrub and herbaceous layers below. As a remnant of the forests of the mid-Atlantic region, the native trees also contributed to the garden’s sense of place. Native trees and shrubs thrive in their indigenous habitats, so reestablishing them in the garden links the created landscape at Brandywine Cottage to the larger wild garden beyond.

If these were the only reasons I had for leaving most of the trees I found here, I still would have been doing a good thing. But I also knew that trees provide both food and habitat for a wide range of wildlife—birds, squirrels and other mammals, and a host of insects from butterflies to beetles. For those of us with trees on our properties, how we maintain them will determine how much benefit they provide for these other forms of life. Dead trees could be considered unsightly, but we leave them standing on our hillside, where the holes in them provide homes for cavity-nesting animals, and the rotting wood provides food for insects, which in turn become food for other animals like woodpeckers. Neither do we remove all fallen twigs or logs from the hillside; we may move this debris if it lands on a choice plant, but otherwise this material is left, along with the fallen leaves, to break down into the humus that acts as the natural fertilizer of the woodland. We sometimes carefully limb up our trees, to allow more light for the understory plants, but we do this purposefully and not often, since once removed, a limb cannot be superglued back on.

Just as trees give visual definition and interest to a landscape, they also define what we can grow beneath them, by the amount of light they let through their canopies, the shallowness of their roots, the amount of moisture they need and, in some cases, the chemicals they secrete. In inventorying the trees, I identified a small stand of Juglans nigra, a native black walnut tree that exudes a chemical called juglone that prevents many other plants from growing beneath it. Someone else might have cut down these trees and planted something more benign, but I took it as my special challenge to find genera that would live in their vicinity. Over the years I have developed a good list— Aucuba, Smilacina, Asarum, Pulmonaria, Convallaria, Helleborus, Hosta, Disporum, Sanguinaria, Cimicifuga, Galanthus, Tricyrtis—with which to make interesting combinations and layers in this part of the garden.

On the down side, over time I discovered a number of plants that simply will not grow here. Most moisture-loving plants have a hard time, along with those that need acidic soil, like many members of the Ericaceae. In the South, I had grown to love evergreen azaleas, and when I moved to Brandywine Cottage, I blithely assumed that they were easy to grow. It was difficult for me to accept that many of them liked neither the pH nor the dryness of the soil in my northern garden. Eventually I learned that the deciduous azaleas do much better for me, but I killed a number of plants in the learning process.

This list of failures could be much longer—I have friends who save all the labels of the plants they have killed as a reminder not to try them again—but I would rather not dwell on what dies when there are so many plants that live and so many new ones to try. I believe that any resourceful gardener can come up with a satisfying palette of plants that will thrive on any particular site. For me, some of the plants that thrive here turned out to be ones I already loved, like hellebores (along with many members of their family, Ranunculaceae). Others I tried after seeing them growing well in similar conditions elsewhere, and when they did well here too, I fell in love with them. In Italy, I saw Arum italicum thriving on a dry hillside, and I came home, planted it on my own dry hillside, and have loved it ever since. It is good advice, in the garden and beyond, to love what loves us back, and not to covet what loves the gardens of others.

In late March, it is “all systems go!” for the borders surrounding the vegetable garden. After cutting everything back, putting down a light mulch, and painting the fence if necessary, it is time for us to step back and let the plants perform.

For anyone trying to create a garden, layered or not, it is crucial to define the extent to which you will pamper your plants to achieve the look and effects you desire. It makes no sense to plant moisture-lovers unless you have the water to support them, or to plant hybrid tea roses unless you commit to a fertilization and pesticide-application regimen to keep them looking good. Knowing how much time and effort you are willing to devote to maintenance should play a large part in defining both the plants you will grow and the type of garden you will create.

Although Brandywine Cottage abuts a suburban development, it is too far out in the countryside to be connected to a municipal water supply. We rely on a 360-foot-deep, slow-filling well for all our needs, which means that if we are to “garden with the site,” we have to keep the water needs of the garden to a minimum. We have a lawn, which we seed every year so it at least has a predominance of grass over other green plants, but we do not fertilize or water it. It is not only the lawn that gets little pampering here. Unless the weather is blazing hot and dry for days, we hardly water anything at all, and we rarely use chemical fertilizers.

In creating new beds at the garden’s inception, I tilled in generous amounts of compost and cow manure to add organic matter to the soil. Each year we top-dress the beds with a thin layer of triple-shredded hardwood mulch or leaf mold—so thin that it must be done every year. The idea is not so much to suppress weeds, since this would also suppress the self-sowing plants we like to encourage, but more to feed the soil. Once or twice we have applied low-nitrogen fertilizer in late winter, but we are careful not to overdo this. Too much fertilizer can make plant stems overly long, weak, and floppy. Also, the more fertilizer you use, the more leaves the plants put out and the more water they require. Even if we had a more generous well, we would still choose to grow our plants “lean and mean,” which makes them look more natural, conserves water, and makes the entire garden more sustainable.

A layered garden could be compared with a theatrical production of many acts: a variety of players take center stage at different times. As with stagecraft, the trick is in the timing, making sure that each plant gives up the limelight gracefully to the next plant, and no plants hog the stage or step on another’s toes as they make their entrances and exits. Rather than a comedy of errors (which no gardener wants) or a tragedy (which the weather sometimes forces on us), my goal is to create a sublime horticultural drama, full of surprises that keep the audience engaged.

I much prefer to work with, and thin if necessary, plants that have a vigorous nature than to do extensive horticultural acrobatics to get a plant to grow. I would not want to do without the sky-blue flowers of Symphytum azureum, even though I have to rip much of it out every other year to prevent it from overrunning choice plants like my black hellebores.

Creating these surprises and having them play out in a seamless fashion is a never-ending task. Any garden with a succession of plants grown closely together will have places where vigorous plants butt up against less vigorous neighbors. And it is up to the gardener to arbitrate these territorial disputes and do what needs to be done to assure that the weaker plants get enough space and light to thrive. This editing process is not the same as drawing a line in the bed, and snipping off any part of any plant that dares cross into the territory of another. Editing in a garden, especially one in which a naturalistic effect is desired, needs to be more subtle than that. It can be as simple as nipping off a few leaves from a taller plant that is shading a smaller neighbor, or as drastic as the outright removal of extra plants that have self-sown or spread into another’s territory.

With herbaceous perennials that die back every year, such editing does no permanent harm. Pruning woody shrubs has to be more carefully thought out, to avoid deforming the shape and structure of the plant. One example in our garden is Viburnum rhytidophyllum, which has to be carefully pruned in order to allow a neighboring variegated Cornus mas to grow and express itself.

Other plants we often have to liberate from aggressive neighbors include peonies, irises, epimediums, and kniphofias. With ephemeral plants such as trilliums, Cardamine quinquefolia, and Cypripedium parviflorum (lady’s slipper orchids), as well as many spring bulbs, allowing the foliage to die back naturally without being overshadowed is particularly important, since these plants have only a short window in which to emerge, bloom, and then recharge before going dormant. Sometimes the aggressors are common self-sowing plants that, once removed, end up on the compost pile. But in this collector’s garden, even rarities have their run-ins once in a while. I have a hundred-dollar variegated lily of the valley from Japan that keeps trying to overrun a hundred-dollar clump of galanthus. The consolation is that any division I can pry off the lily of the valley (a beautiful plant, variegated in an unusual spatter pattern) makes a nice gift for a friend, or can be traded with other collectors for plants to add to the mix.

Besides editing, in a garden like ours where both gardeners have high standards for neatness and beauty, weeding and grooming are constant tasks. Michael enjoys cutting back and deadheading more than I do, whereas I enjoy weeding more, so we are well matched in the maintenance department. Herbicides are not an option; hand weeding is the norm in our garden. I like weeding because it gets me up close and personal with my plants and gives me a pleasing sense of accomplishment once the job is done. I especially enjoy this work when I return from a trip, because it gets me up to speed with what might have happened in the garden while I was gone.

I do admit that as an imperfect human being I am not a perfect weeder, and this point was made crystal clear by a garden visitor a few years ago. She noticed a plant with a serrated leaf in one corner of the garden that she thought was a poppy, and called me over to help confirm its identity. What I found was no poppy—it was one of the world’s largest specimens of Taraxacum officinale (dandelion), which I had somehow overlooked in my weeding. As a joke I told her, “It’s a dandelion, but the white-flowered form,” and we laughed as I made a mental note to dig it out as soon as she left. The real joke was that I was only half-joking. I had once been offered T. albidum, the white dandelion from Japan, but in a rare moment of restraint I turned it down.

Long ago I decided I could tolerate a garden that had a few chewed leaves because I would never want a garden without all the living things I love—the birds, bees, butterflies, fireflies, ladybugs, and so many more that might be harmed if I used chemicals to kill the leaf-munching critters. Like the preceding roundabout sentence, life is a circle: everything is interconnected and no one thing can be removed from a system without upsetting the balance. I could add fungi to the list of things I tolerate, like black spot on my roses. I would rather come up with a way to hide the disfigurement (in this case, by growing other plants to hide the denuded canes) than spray a fungicide that might kill more than just the fungus spores.

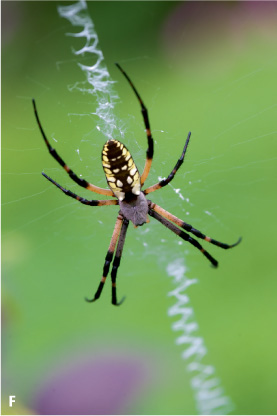

These diminutive garden performers can live in our garden because we almost never use chemical pesticides. Each of these insects is doing something besides providing us with momentary visual pleasure: (A) the praying mantis egg case will hatch out a host of insect-eaters; (B) the ladybugs on the Asclepias specimen are eating aphids; (C) the bee is pollinating Stachys officinalis; (D) and the black swallowtail larva will eventually metamorphose into a fluttering garden diva. (E) Monarch butterflies always add an otherworldly effect to the garden when they stop over on their late summer migration. (F) The “writing spider” (Argiope aurantia) inspires awe because of its size and color, and its unique ornamental web.

Another fungus, powdery mildew, often disfigures the leaves of herbaceous perennials, with phlox and monarda being among the most susceptible. In my garden I now have a pink-flowered strain of Phlox paniculata that has the mildew-resistant cultivar ‘David’ as one of its parents. By continuing to rogue out any mildewed plants before they go to seed, I hope to increase the resistance of this strain as the years go by. Trials in the 1990s at the Chicago Botanic Garden and elsewhere identified resistant varieties of Monarda; I grow one called ‘Jacob Cline’ that looks good most years. Some years it does not—resistance is no guarantee against disease, but only gives the plants a better chance—and there are few sadder sights in a garden than a flower struggling to bloom atop a three-foot stalk of mildewed, dying foliage. If this is how monarda grew in colonial times, no wonder gardeners stripped all the leaves and brewed them into Oswego tea (another common name for the plant).

As breeders have proven with these and other plants, it is possible to select varieties for their disease resistance and not just for the newest flower color or leaf variegation. In Germany, laws prohibiting the application of chemical pesticides on plants in public spaces have created a larger market for disease-resistant varieties. As consumers we have to demand this, not only to make our gardens easier to maintain, but for the sake of our lives, and all the lives that share the garden with us.

Where the pest is an insect, like a Japanese beetle, Michael and I handpick them whenever we can. Having insectivorous mobile garden art, which is how I sometimes view my chickens, also helps keep insect populations down, though if we are not careful to protect them, the chickens can be carried off by four-legged or avian predators and become part of the food chain themselves.

Beyond the harm to local wildlife, any chemicals we used in our garden might end up polluting our well, or run off the property. In a heavy rainstorm, this runoff may end up in nearby Beaver Creek, a tributary to the Brandywine Creek, which runs into the Delaware River, which flows into the Atlantic Ocean. These kinds of direct connections with the outside world exist in every garden, which is why I think we should always aim, in our gardening practices, to do the least harm and the greatest good.