6

SIGNALS FAILURE ON THE LINE TO TANNENBERG

On 15 August Russian 1st Army, based in Vilna under General Pavel von Rennenkampf, drove into northern East Prussia from the east. The other arm of the pincer, Russian 2nd (or Warsaw) Army under General Aleksandr Samsonov had originally been intended for a strike southwards into Galicia, but moved instead northward across the border into East Prussia on 20 August. Between the two prongs of the Russian attack, there was no coordination, partly because of inadequate logistics; partly due to the difficult terrain of the Augustovo Forest and the Masurian Lakes which lay between them; but mostly because the two army commanders were known for refusing to speak to each other, even when face-to-face. Rennenkampf also refused to speak to his own chief of staff or to read any communication addressed to the chief of staff and not to himself. So inadequate were his communications with his front commander, General Yakov Zhilinski at northern front HQ in Bialystok that Zhilinski was reduced to pleading with Stavka for assistance. Five messages were sent from Stavka to Rennenkampf, who did not deign to reply, or to receive an emissary from Grand Duke Nikolai. It says a lot about the senior officers of 1st Army that its cavalry commander, the elderly Khan of Nackichevan was unable to mount a horse because he suffered from piles – and ended by having a nervous breakdown.1

The two Russian armies tasked with the adventure into East Prussia totalled 208 battalions and 228 squadrons of cavalry against less than 100 battalions in German 8th Army opposing them. In terms of military planning, the staff of 2nd Army had arranged for 10,145 hospital beds to be available for casualties from the campaign, a number sufficient only for the victims of syphilis undergoing treatment.2 Fortunately for the enemy, Russian intelligence was generally appalling: on one occasion General Nikolai Russki commanding 3rd Army on the south-western front acted on a war-game assumption that he was outnumbered while actually facing nine Austro-Hungarian divisions with twenty-two of his own.

All sides were already intercepting and/or jamming each other’s diplomatic radio traffic, but military signals interception was in its infancy, although the Germans were sufficiently technically advanced for them regularly to decipher coded communications between the Western Allies in Flanders. Russian military radio communications were transmitted en clair, and thus easily intercepted by front-line German signals intercept units, which were so efficient that Marshal Joffre’s Order of the Day for the Battle of the Marne in September 1914 was deciphered and read by the German High Command before it had reached the French front line.3

After Rennenkampf’s initial victories at Stallupönen (modern Nesterov) on 17 August and Gumbinnen (modern Gusev),4 on 20 August, Prittwitz learned of the approach of Samsonov’s army, and panicked, ordering a strategic retreat all the way back to the River Vistula – which meant evacuating most of East Prussia. On reflection, he amended this order to a retreat to the River Passarge,5 which still left the 50 × 20 mile German enclave of the Königsberg peninsula cut off and relying on re-supply by sea. As head of OHL, Helmuth von Moltke immediately decided to sack Prittwitz and telegraphed on 22 August to 66-year-old retiree General Paul von Hindenburg, calling him back to the colours. Hindenburg’s soldierly reply was a 2-word telegram: Bin bereit – am ready – after which he got on the next train to Hannover and a return to military life. Moltke also sent a letter by courier to Major General Erich Ludendorff, appointing him chief of staff to Hindenburg and ending: ‘There is no one I trust more than you. Perhaps you can save the situation in the East.’ That perhaps is a measure of the alarm engendered in Berlin by Prittwitz’s panic.

After retirement, Hindenburg lived on his estate in East Prussia, where his wife had wanted to plant apple trees, until he remarked dryly that it would be pointless because, by the time they were mature, the area would be occupied by Russians. In fact, it was occupied by Poles, but the apples would not have filled German bellies either way. Hindenburg devoted three years in walking tours of the province, during which he familiarised himself with the topography, noting probable avenues of invasion by Russia and the best ways of frustrating any such incursions. After the defeat in 1918, Hindenburg became the great apostle of the Dolchstosslegende – the stab-in-the-back fantasy that Germany’s defeat on the battlefield had little to do with Allied superiority in arms and manpower, even after the arrival in Europe of US troops and materiel, but was mainly due to treachery by the civilian population, by mutineers and Communists – and eventually, of course, the Jews. So it was that he, as president of the Weimar Republic, summoned Adolf Hitler to become chancellor of the first Nazi government, although privately referring to him as ‘the Austrian corporal’. Ludendorff, who had been one of the co-accused at the 1924 trial of Hitler’s cabal, had by then changed sides and wrote scathingly to his old commander about Hitler’s rise to power. But all that was a long way in the future.

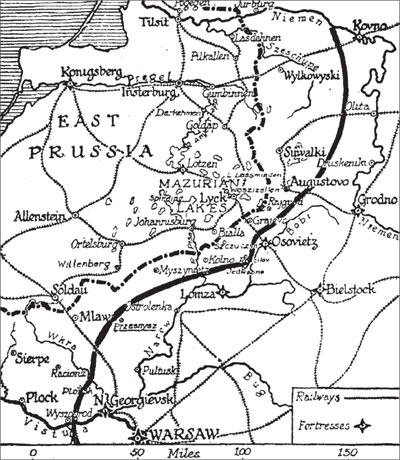

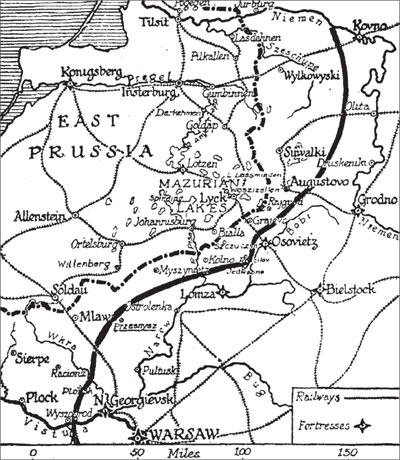

East Prussia – the area invaded by Rennenkampf and Samsonov. Contemporary map with anglicised place names.

Inspecting the south-western front a long way south at Rovno, where he met General Nikolai Ivanov, the genial 55-year-old front commander, Colonel Knox described his new host as being ‘simple and unpretentious in his manner’, having worked his way up the ladder from humble beginnings. This was reflected in the fare at table. Russian peasants used to say, ‘Shchi da kasha, pishcha nasha’ – cabbage soup and gruel of buckwheat, that’s all we ever get to eat. It was also what Knox got to eat at Ivanov’s table, where no wine was to be served until the war was ended. It amused the English observer to see Princes Dolgoruki and Karakin imbibing lemonade instead.

After the meal, the officers went outside to talk to the troops and Knox spoke to one ‘fine fellow, over six feet tall, belonging to the 4th Heavy Artillery Division.’ This reservist told him that he had left a wife and five children at home. When assured by the officers that he would survive, the artilleryman shook his head sadly. ‘It is a wide road that leads to the war,’ he said, ‘and a narrow path that leads home again.’ Knox had heard General Samsonov complaining about the problems of launching an offensive in these regions, purposely left roadless by the Russian government to delay any enemy incursions. Heading towards the town of Dubno – on horseback, of course – Knox recorded passing a column of the 127th Infantry Regiment plodding along through the deep mud under torrential rain at a pace little faster than marking time, and with a look of unreasoning misery on their faces. He summed them up as unlikely to win their imminent contact with the enemy.6

The new command team taking over German 8th Army 400 miles to the north-west in East Prussia decided to adopt a plan by Prittwitz’s deputy operations officer Colonel Maximilian Hoffmann – a baby-faced officer with full lips and pince-nez spectacles that belied a shrewd military mind. Like Knox a fluent Russian-speaker who had spent several years in Russia, Hoffmann had witnessed the mutual recriminations of Samsonov and Rennenkampf after the defeat of Mukden7 during the Russo-Japanese war of 1904, and was certain that it would be possible to surround Samsonov’s army long before Rennenkampf came to its rescue – and trap it in what they called eine Kesselschlacht or ‘killing cauldron’. Accordingly, General Hermann von Francois’ I Corps was transported by the efficient German rail network to confront the left flank of Samsonov’s army, where some inconsequential skirmishes had already taken place, while XVII Corps and I Reserve Corps, commanded by Generals Mackensen and von Below, were held ready to march south and tackle Samsonov’s right wing. The inherent risk in Hoffmann’s plan was that the outer defences in the south of the Königsberg enclave would be substantially depleted in manpower until German 1st Cavalry Division was redeployed to screen them, and that Rennenkampf’s 1st Army could swing south to threaten the German left flank in order to take the pressure off Samsonov.

Taking command on 23 August, Hindenburg and Ludendorff immediately approved Hoffmann’s plan. Still advancing north-westwards on the following day, Samsonov was having logistics problems and understood from General Zhilinski in Byalistok that all was going according to Plan 19A in the north. He had no idea that Rennenkampf had paused to regroup after Gumbinnen instead of pressing on in a south-westerly direction to effect the planned link-up of the two armies. Lindendorff ordered General von François’ I Corps to begin its attack on Samsonov’s left flank on 25 August but François held back for two further days, protesting to Ludendorff and Hoffmann, who travelled in person to put pressure on him, that his artillery was still in transit. François’ correct assessment of the situation, and his failure to attack prematurely, nevertheless earned his superiors’ lasting hatred and effectively stunted his military career after Hindenburg and Ludendorff were subsequently given command of all the German armies.

Back in Berlin, Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke was uneasy about the situation in East Prussia, surprising Ludendorff by telephoning him to say that he was detaching a cavalry division and three army corps from France and sending them to the Russian front. Knowing that Schlieffen’s dying words had been, ‘Keep the right flank strong’, Hindenburg and Ludendorff both considered that the promised reinforcements could be far better used in France, where the drive to surround Paris was already slowing down because the right flank was not sufficiently strong. Although they protested that they did not need reinforcements in East Prussia, these were sent anyway, proving Schlieffen’s dying fears prophetic as the weakened right flank was brought to a halt well short of its objective.

Shortly after the conference with François, on 25 August Hoffmann received two clear-language signals intercepts of Russian transmissions. The one from Rennenkampf’s HQ revealed not only the exact distance then separating the two Russian armies but also gave away the compass bearing on which 1st Army was advancing. The intercept from Samsonov’s HQ revealed how he believed erroneously that the German forces ahead of him were withdrawing northwards. In fact, by pursuing them, he was leading his army further into a trap. Ludendorff wondered whether the intercepted signals could have been a ruse because it seemed incredible that neither would be in code, but Hindenburg supported Hoffmann’s assessment that they were genuine. Accordingly, German XX Corps was moved into position between Allenstein and Tannenberg.

There, German XVII Corps attacked Samsonov’s right flank near Seeburg and Bischofstein on 26 August. The battle is rather confusingly referred to in German war history as the Battle of Tannenberg although geographically at some distance from there. This was a later idea of Hoffmann’s, to expunge the memory of the humiliating defeat of the Teutonic Knights in that area by a Polish-Lithuanian army in 1410. German XX Corps was able to hold a line near Tannenberg, while the Russian 13th Corps drove unopposed on Allenstein. In twenty-four hours, German I Corps under François had neutralised Samsonov’s left flank. For whatever reason, he disregarded this and obstinately drove his five centre divisions onwards to their doom after German XVII Corps turned his right flank. The next day, General François used his artillery and now adequate stock of shells to break through Russian 1st Corps. Colonel Knox commented that one Russian regiment had nine out of sixteen company commanders killed; a company that began the action 190-strong lost all its officers, had 120 other ranks killed and most survivors wounded.8 But worse was to come. Russia still had vast reserves of men, permitting the replacement of a quarter-million men taken prisoner or killed at Tannenberg and the First Battle of the Masurian Lakes. What it did not have was an endless supply of rifles, from which to replace the quarter-million rifles lost with these men.

Hoffmann received another uncoded intercept, from Zhilinksii to Rennenkampf, which indicated clearly that Russian 1st Army had not been ordered to march to Samsonov’s support with all possible speed. On the strength of this, Ludendorff despatched von Below from Bischofsburg to strengthen the German centre, with Mackensen ordered south to close the ring around Russian 2nd Army.

Hoping to save the bulk of his army, Samsonov withdrew Russian 13th Corps from the drive on Allenstein, to redeploy it against the German line east of Tannenberg. On 28 August, as German forces squeezed both Russian flanks, Samsonov at last panicked, with his forces dispersed and reinforcements unable to reach him from the rear. That evening, he ordered a general withdrawal. Even had Rennenkampf been ordered to come to his aid, it was now too late, as the way was blocked by fast-moving German cavalry. Ordering 2nd Army to fall back to the southwest and regroup, Samsonov was wrong-footed by another refusal of François to mindlessly obey orders – in this case, to move north in case Rennenkampf, by forced marches, did come to Samsonov’s support. Instead, François ordered I Corps to drive eastwards to the south of Samsonov’s centre and block its retreat to safety in the Polish salient. This insubordination contributed greatly to the German victory, but did not restore him to Hindenburg’s favour.

Samsonov’s situation became completely unsustainable after German XVII Corps joined up with I Corps on 29 August. Something of the confusion and chaos can be gleaned from Knox’s diary. His entry for that day was a pious hope that Samsonov had not underestimated the strength of the German forces advancing towards him from the west and north-west. Chatting to a French pilot named Poiret, who had been flying dangerous low-level reconnaissance missions for the Russians north-west of Neidenburg (modern Nidzica), where his observer had been wounded that morning by shrapnel in the leg, Knox was told that the pilot’s assessment, based on observation, was that Samsonov was about to be hit by three entire army corps. Visiting the field hospital to enquire after Poiret’s wounded observer, he found little sign of preparation for casualties. With no beds provided, the wounded were lying haphazardly on the floor, the lucky ones having at best some straw to lie on.

During the visit, the sound of nearby rifle fire caused Knox to run outside and look up. An enormous Zeppelin was hovering overhead at a height of 900 to 1,000m. It dropped four bombs in quick succession, killing six men and wounding fourteen others. Rifle fire being totally useless against such a target, a nearby battery was brought into action, damaging the airship and forcing it to land. The crew was taken prisoner, to everyone’s great relief.

There were few women to be seen in this scene of desolation. Watching the survivors of two army corps straggle into the town of Ostrolenka, Knox learned that General Martos of 15th Corps had been injured when a German shell landed on his car. With him at the time was a German-speaking officer’s wife called Aleksandra Aleksandrovna, who had been acting as his interpreter. Apparently uninjured, she panicked, jumping out of the car after the explosion and ran off into the forest, never to be seen again.

Realising too late that his army was surrounded and trapped, Samsonov continued the hopeless fight for two further days until surrendering at a cost of 92,000 officers and men taken prisoner, another 50,000 killed and wounded and the loss of more than 400 guns.9 By then, Knox was back in Warsaw, which had been bombed several times by German aircraft and airships. More alarmingly, he found that the massive Poniatovski bridge over the Vistula was being wired for demolition. The families of government officials were already leaving for the safety of Mother Russia, with their menfolk preparing to follow them at a moment’s notice. A member of the State Duma, or Russian parliament, told him that Stavka envisaged losses of about 300,000 men in the defence of the city. Meeting the Frenchman Poiret again, he found him pessimistically saying to all and sundry that, if the Russians allowed Warsaw to be taken, it showed they were beaten.

So much Russian equipment had been abandoned on the field of battle by Samsonov’s men – including all their guns and transport – that more than fifty freight trains were required to transport it all back to Germany for further use. German casualties totalled less than half the Russian losses.

Like Rennenkampf, Samsonov had made his reputation as a cavalry commander. This, as Knox commented, was of no value in preparing the two generals to command large numbers of troops against their German opponents who were ruthless professional soldiers trained in the efficient, modern deployment of infantry and artillery, as well as the cavalry, and also knew the terrain of East Prussia intimately.10

In the early hours of 28 August Samsonov made what Knox called a ‘mad decision’, cutting himself off from his base and half his forces and sending much equipment, including all the wireless transmitters and receivers back to Russia.11 Knox found the general and his staff sitting on the ground, poring over their maps. Samsonov stood up and ordered eight men of the sotnya12 of Cossacks that acted as his bodyguard to hand over their mounts. Privately, he told Knox that the position was very critical, and advised him to head for the rear while there was still time. Samsonov then rode off to see how things were going at the front with his own eyes, as he had been accustomed to doing in Manchuria during the Russo-Japanese war of 1904–5. The eight officers and the rest of the sotnya rode off to the north-west on the Cossack ponies, while Knox was driven slowly back to Neidenburg, wondering whether the town with its Teutonic castle was still in friendly hands. In the town, badly damaged by the Russian artillery in Samsonov’s attack, everything was quiet, although shells were bursting 2 or 3 miles to the north-west. Walking wounded and stragglers were wandering aimlessly about among the ruins. One soldier, who had been caught looting, was screaming in agony as he was flogged with a knout by Cossacks outside the commandant’s house. His ordeal ended when a single shot was fired as the officers drove out of town.13

Although able at the last possible moment to escape from the pocket with about 10,000 officers and men, Samsonov and his staff had no contact or communication with the outside world after the evening of 29 August and were finally accompanied only by the remnant of their Cossack escort. From various survivors’ accounts, the story of their final hours was gradually pieced together. After being out of communication for three whole days, Samsonov and his staff officers became lost after he told the Cossack escort, who had suffered severely in charging a machine gun position, to shift for themselves. On the night of 29–30 August the small group of officers was stumbling on foot through the forest north of the railway line from Neidenburg to Willenberg. Holding hands to avoid losing one another in the darkness, they had one compass, but no maps. As Knox commented, Russian maps were in any case inaccurate and badly printed, but to have no maps at all defies imagination. Finally the matches they were striking to consult the compass gave out. Samsonov kept saying, ‘The Tsar trusted me. How can I face him after such a disaster?’ He went off into the darkness and the other officers heard a shot. After searching unsuccessfully for his body, they managed to reach Russian-held territory, having covered 40 miles on foot. Samsonov’s corpse was later recovered by German troops and given a respectful military funeral.14

The capital named St Petersburg by Peter the Great – the name was now thought to be too Germanic – was rechristened on 31 August with the Slavic name Petrograd. To the north of the great Russian defeat at Allenstein/Tannenberg, Rennenkampf still had fourteen divisions, a rifle brigade and five cavalry divisions, with Russian 10th Army on its way to join him with six more combat-ready divisions. Hoffmann immediately set in motion the mammoth manoeuvre of moving German 8th Army, hampered by the need to guard and feed all those prisoners, north-east to tackle Rennenkampf. His plan was classically simple: splitting forces so that the right wing could swing to the north-east through the Masurian Lakes to cut the Russian lines of communication and interdict the arrival of 10th Army, while the main force engaged Russian 1st Army. Underestimating the speed at which well-trained German troops could be redeployed on their home ground by a railway system that enabled large numbers of men to be transported long distances very rapidly, Rennenkampf failed to secure his position while this was still possible.

Observing the chaos all around him, Knox noted that Army Orders reached local commanders sometimes as late as 10 a.m., so that troops being redeployed could only set off on foot at noon. Communication between the various corps had to be maintained by wireless but, as many staffs had not a single officer who could encipher or decipher, the messages were sent in clear, allowing the German intercept stations to prepare for every move. Reaching Allenstein on 27 August, many of Rennenkampf’s soldiers believed it to be Berlin.15 The sight of a modern, neat, tidy German city defied the imagination of a Siberian peasant conscript, used to mud roads and primitive housing unchanged since the Middle Ages. How could the enemy possess two such prosperous cities? he must have wondered. The conscript would have had as little idea of European geography as a Briton would know of Omsk or Tomsk. Four decades later, in 1958 when an RAF linguist colleague of the author asked a sentry at the small Soviet war memorial in West Berlin in Russian how he liked being stationed in Berlin, the sentry replied, ‘Chto eto takoye, Berlin?’ ‘What’s Berlin?’

Colonel Knox rightly considered it his duty to pass back to London the gist of his observations of the disastrous East Prussia campaign. Asking permission of front commander General Zhilinski to return to the renamed capital, from where he could send his despatches, he was informed that protocol demanded he must first obtain permission from Grand Duke Nikolai. Stavka was ignorant of the enemy’s movements and corps commanders were informed only of the immediate objectives of neighbouring units, but told nothing of what had happened to Samsonov’s army. So this was an excuse to keep him waiting in Bialystok for three days because Zhilinski feared the consequences of the only foreign officer to observe the debacle talking about it in Petrograd, where he was trying to cover his own inadequacy by accusing Rennenkampf of failing to move to Samsonov’s assistance and turning a personal profit from supplies contracts. However, Rennenkampf turned to his friends in the cavalry establishment, who persuaded the Grand Duke that the whole debacle was all Zhilinski’s fault. Nikolai believed them and told the Tsar, who dismissed Zhilinski, leaving Rennenkampf to fight badly another day.16 During his enforced wait at Stavka that ended on 6 September, Knox noted that the nerves of all ranks were so shaky that troops fired at every aircraft appearing in the skies and occasionally even at their own officers’ automobiles.

Within a week of the German victory at Tannenberg/Allenstein, eight German divisions confronted Rennenkampf with seven more, including two of cavalry, threatening his exposed left flank. Analysts have interpreted this to mean that Hindenburg and Ludendorff were not so much trying to annihilate Russian 1st Army as to force it to retreat back towards its start line at the border. If that was the plan, it worked even better than could have been expected. On 7 September, three German divisions attacked the Russian left flank in the First Battle of the Masurian Lakes, meeting sustained Russian resistance.

On 10 September Rennenkampf sacrificed two divisions to gain the time to disengage his main force in a strategic retreat. Slowed down by the need to march eastwards through their own chaotic, horse-drawn supply trains still heading for the abandoned front line, his men nevertheless managed to make 20 miles a day, travelling faster than their pursuers, who made no serious attempt to block their retreat to the frontier. Whether this was a retreat or a rout, is debatable. Certainly it was a costly manoeuvre that left a further 200 artillery pieces behind and the better part of two whole armies – totalling around a quarter-million officers and men – in East Prussia as casualties or prisoners by the time the German spearheads reached the border on 13 September and the front stabilised.

The Russian attack on East Prussia did arguably disrupt OHL’s execution of the modified Schlieffen Plan in France and play a part in preventing the fall of Paris, but its failure was a high price to pay for helping the Western Allies because it lowered morale at all ranks in the Russian armies and triggered a number of retreats over the next twelve months.

NOTES

1. Stone, pp. 58–9.

2. Ibid, p. 49.

3. G. Elliott and H. Shukman, Secret Classrooms (London: St Ermin’s Press/Little, Brown, 2002), p. 173.

4. In Kaliningrad oblast.

5. Knox, p. 56.

6. Ibid, pp. 50–1, 61 (edited).

7. It was widely believed that they had actually come to blows.

8. Knox, pp. 64–5.

9. Stone, p. 66, although Russian casualties are approximate.

10. Knox, p. 85.

11. Ibid.

12. A squadron, nominally of 100 riders.

13. Knox, pp. 70–2 (edited).

14. Ibid, pp. 82, 86–7.

15. Ibid, p. 84 (edited).

16. Stone, footnote to p. 95.