Introduction

Overview

Paul’s purpose in writing connects with the situation of the church in Rome and his own circumstances and ministry plans. He seems to have not one but several reasons for writing Romans.

One reason Paul writes this letter is to unify the different house churches. Notice the theme of “peace” that runs through the entire letter (Rm 1:7; 2:10; 3:17; 5:1; 8:6; 14:17, 19; 15:13, 33; 16:20). Paul’s attempt to heal this division is most apparent in his discussion of the “weak” and the “strong” in 14:1–15:13. On the one hand, the “weak” Jewish Christians were probably condemning Gentile Christians for failing to observe certain food laws or keep particular holy days. They believed strongly in the importance of religious rituals in the Christian life. On the other hand, the “strong” Gentile Christians probably looked down on the Jewish Christians for not taking their freedom in Christ seriously enough. Paul rebukes both groups for placing their own personal convictions above the gospel itself. Paul can understand both worlds quite well as a Jew (see 9:1–5) who has also been commissioned to serve as the “apostle to the Gentiles” (11:13; cf. 1:5; 15:16). He hopes this clear and comprehensive explanation of the gospel of Jesus Christ will refocus both groups on what is most important and, as a result, unify the church in Rome.

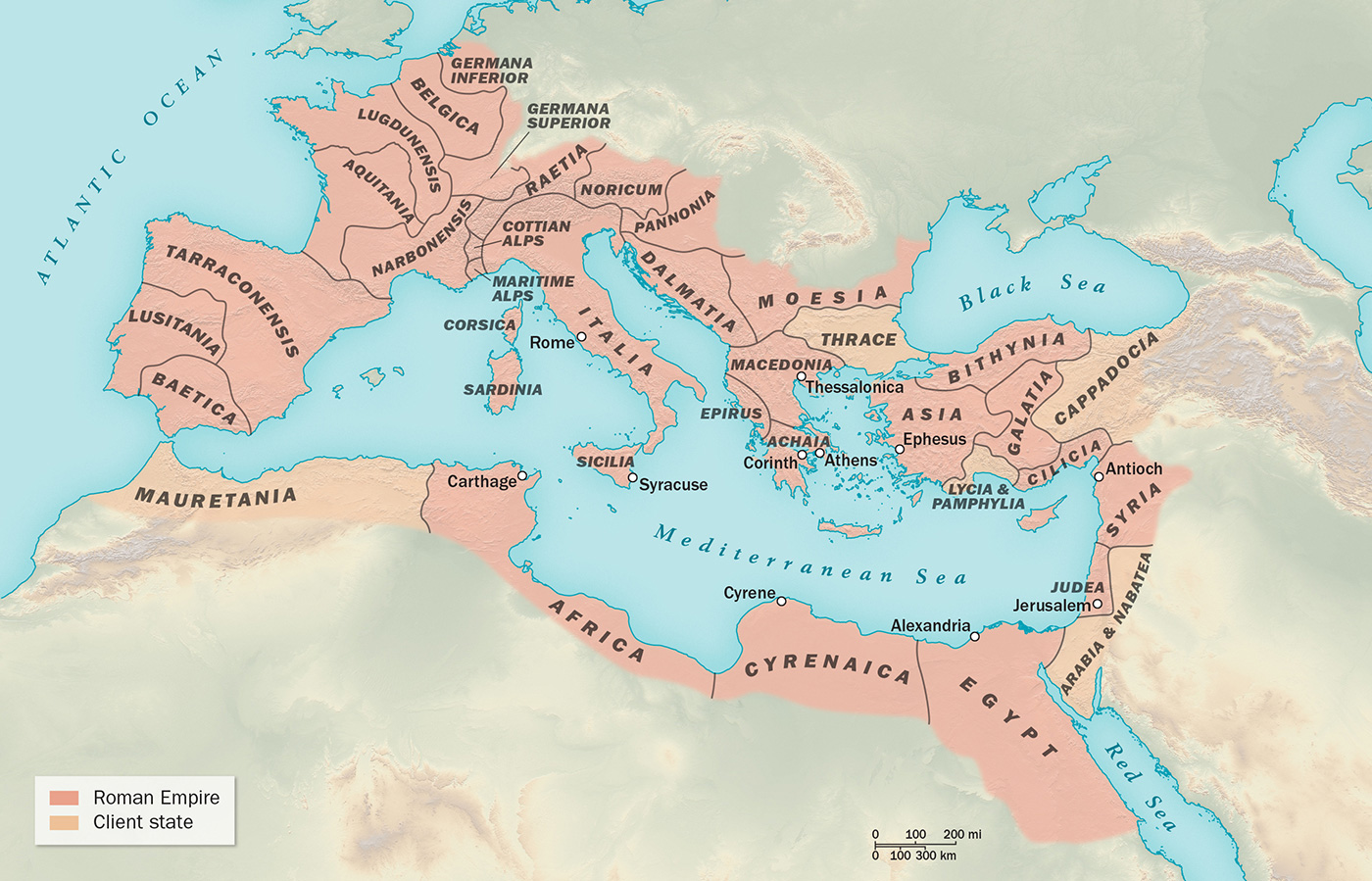

The Location of Rome

Rome stood on the western side of the Italian peninsula. It was the center of a vast empire that in Paul’s day reached from western Spain to Armenia and from northern Gaul to the upper Nile region.

Paul’s own circumstances also lead him to write the letter. He plans to take the collection from the Gentile churches back to the poor Jewish Christians in Jerusalem (15:25–27). Then he hopes to visit Rome on his way to Spain (15:22–29). He wants to encourage and strengthen the church in Rome (1:8–15), but he’s also counting on their financial support for his mission trip farther west (the term for “assist” in 15:24 often refers to financial assistance). The heart of Romans may be summarized in this way:

| The gospel | → | unity in the church | → | mission of the church |

With his forceful and comprehensive account of the good news (gospel) of a righteousness from God (1:17), Paul attempts to persuade the Gentile and Jewish Christians in Rome to unite. A church unified around the gospel of Jesus Christ is a church on mission. [The City of Rome]

Date and Historical Context

Paul provides information that helps us situate the letter in its historical context. He informs the Roman Christians that he has brought to an end his work as a pioneer missionary among Gentiles in the eastern regions of the Mediterranean (15:18–23). He intends to visit them in Rome on the way to Spain, where he wants to open up a new region for the proclamation of the gospel (15:23–24, 28–29). Before coming to Rome, something he has wanted to do for some time (1:13), he will first travel to Jerusalem in order to hand over the funds that were collected in the churches he established in Macedonia and Achaia (15:25–28). He asks the Roman Christians to pray for him as he travels to Jerusalem, as both his safety and the acceptance of the collection funds are uncertain (15:30–32).

Paul wrote his letter to the Christians in Rome in the winter and early spring of AD 56–57 while staying in Corinth. After he completed his missionary work in Ephesus, where he had worked from AD 52 to 55 (Ac 19), he visited the churches in Macedonia and Achaia (Ac 19:21). He stayed in Corinth for three months (Ac 20:2–3), waiting for shipping on the Mediterranean Sea to resume in the spring (Ac 20:3), as he wanted to be in Jerusalem for the day of Pentecost (Ac 20:16). Paul’s host during this time was Gaius (Rm 16:23), presumably the same Christian whom he baptized when he established the church in Corinth (1 Co 1:14).

Audience

The addressees of the letter are the Christians in the city of Rome (1:6–7). The history of the church in the capital of the Roman Empire is known only in broad outline. Scholars agree that the origins of the church in Rome are connected with Jews living in Rome who were converted to faith in Jesus as Messiah. The questions of when and where Roman Jews first came into contact with the gospel of Jesus Christ have been answered in different ways. Jews of Rome who visited Jerusalem on the occasion of Pentecost in AD 30 could have met Peter and the other apostles, been converted to faith in Jesus the Messiah, and taken the message of Jesus back to Rome. Luke mentions “visitors from Rome” among the pilgrims at Pentecost (Ac 2:10). Jews of Rome could also have come into contact with Jewish Christians in other cities in the eastern Mediterranean at an early date, perhaps in Antioch in Syria. Peter might have traveled to Rome when he left Jerusalem because of the persecution instigated by Herod Agrippa I in AD 41/42 (Ac 12:17).

By the early 40s, there were Jewish Christians in Rome. The Roman historian Cassius Dio mentions an edict of Claudius issued in AD 41 intended to quell unrest in the Jewish community of Rome, commanding the Jews to adhere to their ancestral way of life and not to conduct meetings. This edict probably presupposes missionary activity of Jewish Christians in the synagogues of the city of Rome. The existence of Jewish Christians in Rome is probably the background for another edict of Claudius. In AD 49 the emperor ordered the expulsion of the Jews from Rome. Suetonius reports measures undertaken by Claudius against people of foreign birth, pointing out that “since the Jews constantly made disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus, he expelled them from Rome” (Claudius 25.3–4). The disturbances were probably provoked by the missionary outreach of Jewish Christians who preached Jesus as Messiah (Gk christos). Luke reports that in Corinth Paul met the Jewish couple Aquila and Priscilla, who had recently come from Italy because “Claudius had ordered all the Jews to leave Rome” (Ac 18:2). Paul arrived in Corinth in AD 50, just after the expulsion of the Jews from Rome.

Rome

In the first century, Christians in Rome were largely concentrated in the Transtiberine region (home to a large Jewish population) and along the Appian Way near the Porta Capena, two swampy areas where the poorest populations lived. The Aventine Hill, home to many aristocrats, was likely the location of the church of Priscilla and Aquila.

When Paul wrote to the Roman Christians in AD 56/57, seven years had passed since Claudius’s edict of AD 49. By this time some of the expelled Jews had returned to the city, including some of the Jewish Christians who had been forced to leave, such as Aquila and Priscilla (Ac 18:2; Rm 16:3). However, the expulsion of the Jews must have changed the composition of the church membership considerably. While the church originated among Jewish believers and probably had a majority of Jewish believers before AD 49, it had become a predominantly Gentile church by the time Paul wrote his letter. This is also suggested by Paul’s argument in Rm 11:17–24.

Bust of Emperor Claudius, who ruled the Roman Empire from AD 41 to 54

Why did Paul write to the Roman Christians? The answer to this question needs to take into account Paul’s goal to recruit the Christians in Rome for his plan to begin missionary work in Spain (15:24). As a letter of introduction to the Christians in Rome, Paul’s letter is rather long—Cicero’s letters range from 22 to 2,530 words, Seneca’s from 149 to 4,134 words, while Paul’s letter to the Romans has 7,111 words (in the Greek text). We also must take into account that Paul was about to visit Jerusalem, where he would meet traditionalist Jewish Christians who believed that Gentile followers of Jesus should submit to Jewish law and to circumcision. The questions about the gospel he preached are the same questions that were controversial during the previous two decades, in which he had been active as a missionary. Paul thus wrote a long letter in which he provided a synthesis of the gospel of Jesus Christ he had been preaching. He had been called by God on the road to Damascus to proclaim the crucified and risen Lord Jesus Christ among the Gentiles (Gl 1:15–16). The fundamental convictions that Jesus Christ is the only source of salvation for both Gentiles and Jews (Rm 1:16) and that Jesus Christ unites Jews and Gentiles in the one new community of the followers of Jesus (Gl 3:28) are central elements of what Paul calls the “truth of the gospel” (Gl 2:5, 14). These convictions raise questions about several matters: (1) how Jewish Christians should view Gentiles (and Gentile Christians) and how Gentile Christians should view Jews (and Jewish Christians); (2) the sin of Gentiles and the sin of Jews; (3) God’s condemnation of sinners and God’s salvation, which is now available to all through Jesus the Messiah; (4) the validity of the Mosaic law; (5) God’s righteousness in terms of the reality of everyday life; and (6) God’s righteousness in the context of the reality of his promises to Israel and of Israel’s rejection of the Messiah.

Outline

1. Introduction (1:1–17)

A. Sender, Address, and Salutation (1:1–7)

B. Thanksgiving and Petition (1:8–15)

C. Theme of the Letter (1:16–17)

2. The Gospel as the Power of God for Salvation to Everyone Who Has Faith (1:18–15:13)

A. The Justification of Sinners on the Basis of Faith in Jesus Christ (1:18–5:21)

B. The Reality of Justification by Faith in the Life of the Christian (6:1–8:39)

C. The Reality of Justification by Faith in Salvation History (9:1–11:36)

D. The Reality of Justification in the Christian Community (12:1–15:13)

3. Conclusion (15:14–16:27)

A. Paul’s Missionary Work and Future Travel Plans (15:14–33)

B. Greetings (16:1–24)

C. Final Doxology (16:25–27)