It was August 4th, and I guess it already had been for a while. To be totally honest I didn’t even notice the change at first. My life was already serving up these big fat sweltery summer days anyway, one after the other, each one pretty much exactly the same as the one before it … probably a more powerfully alert and observant person would have picked up on the change sooner.

What can I say, it was summer. It was hot. Anyway, here’s what was going on: Time had stopped.

Or it hadn’t stopped, exactly, but it got stuck in a loop.

Please believe me when I say that this is not a metaphor. I’m not trying to tell you that I was really bored and it seemed like summer would never end or something like that. What I’m saying is, the summer after my freshman year of high school, the calendar got to August 4th and gave up: Literally every single day after that was also August 4th. I went to bed on the night of August 4th. I woke up, it was the morning of August 4th.

The chain had slipped off the wheel of the cosmos. The great iTunes of the heavens was set on Repeat One.

As supernatural predicaments go it wasn’t even that original, given that this exact same thing happened to Bill Murray in Groundhog Day. In fact one of the first things I did was watch that movie about eight times, and while I appreciate its wry yet tender take on the emotional challenges of romantic love, let me tell you, as a practical guide to extricating yourself from a state of chronological stasis it leaves a lot to be desired.

And yes, I watched Edge of Tomorrow too. So if I ran into an Omega Mimic, believe me, I knew exactly what to do. But I never did.

If there was a major difference between my deal and Groundhog Day, it was probably that unlike Bill Murray I didn’t really mind it all that much, at least at first. It wasn’t freezing cold. I didn’t have to go to work. I’m kind of a loner anyway, so I mostly took it as an opportunity to read a lot of books and play an ungodly amount of video games.

The only real downside was that nobody else knew what was happening, so I had nobody to talk to about it. Everybody around me thought they were living today for the first time ever. I had to put a lot of effort into pretending not to see things coming and acting surprised when they came.

And also it was boiling hot. Seriously, it was like all the air in the world had been sucked away and replaced by this hot, clear, viscous syrup. Most days I sweated through my shirt by the time I finished breakfast. This was in Lexington, Massachusetts, by the way, where I was already stuck in space as well as time, because my parents didn’t want to pony up for the second session of summer camp, and my temp job at my mom’s accounting firm wouldn’t start till next week. So I was already killing time, even as it was.

Only now, when I killed time, it didn’t stay dead. It rose from the grave and lived again. I was on zombie time.

Lexington is a suburb of Boston, and as such is composed of a lot of smooth gray asphalt, a lot of green lawns, a lot of pine trees, a bunch of faux-colonial McMansions, and some cute, decorous downtown shoppes. And some Historick Landmarks—Lexington played a memorable though tactically meaningless role in the Revolutionary War, so there’s a lot of historical authenticity going on here, as is clearly indicated by a lot of helpful informational plaques.

After the first week or so I had a pretty solid routine going. In the morning I slept through my mom leaving for work; on her way she would drop my impressively but slightly disturbingly athletic little sister at soccer camp, leaving me completely alone. I had Honey Nut Cheerios for breakfast, which you’d think would get boring fast, but actually I found myself enjoying them more and more as time went by. There’s a great deal of subtlety in your Honey Nut Cheerio. A lot of layers to uncover.

I learned when to make myself scarce. I found ways to absent myself from the house from 5:17 p.m. to 6:03 p.m., which is when my sister muffed the tricky fast bit in the third movement of Vivaldi’s Violin Concerto in A Minor seventeen times straight. I generally skipped out after dinner while my parents—they got divorced a couple of years ago, but my dad was over for some reason, probably to talk about money—had a nastier-than-usual fight about whether or not my mom should take her car into the shop because the muffler rattled when you went over bumps.

It put things in perspective. Note to self: Do not waste entire life being angry about stupid things.

As for the rest of the day, my strategies for occupying myself for all eternity were mostly (a) going to the library, and (b) going to the pool.

Generally I chose option (a). The library was probably the place in Lexington where I felt the most at home, and that’s not excluding my actual home, the one where I slept at night. It was quiet at the library. It was air-conditioned. It was calm. Books don’t practice violin. Or fight about mufflers.

Plus they smell really good. This is why I’m not much of a supporter of the glorious e-book revolution. E-books don’t smell like anything.

With an apparently infinite amount of time at my disposal, I could afford to think big, and I did: I decided to read through the entire fantasy and science fiction section, book by book, in alphabetical order. At the time, that was pretty much my definition of happiness. (That definition was about to change, in a big way, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves.) At the point where this story starts it had been August 4th for I would say approximately a month, give or take, and I was up to Flatland, which is by a guy named, no kidding, Edwin Abbott Abbott.

Flatland was published in 1884, and it’s about the adventures of a Square and a Sphere. The idea is that the Square is a flat, two-dimensional shape, and the Sphere is a round, three-dimensional shape, so when they meet the Sphere has to explain to this flat Square what the third dimension is. Like what it means to have height in addition to length and width. His whole life, the Square has lived on one plane and never looked up, and now he does for the first time and, needless to say, his flat little mind is pretty much blown.

Then the Sphere and the Square hit the road together and visit a one-dimensional world, where everybody is a near-infinitely thin Line, and then a zero-dimensional world, which is inhabited by a single infinitely small Point who sits there singing to himself forever. He has no idea anybody or anything else exists.

After that they try to figure out what the fourth dimension would be like, at which point my brain broke and I decided to go to the pool instead.

You might jump in at this point and say: Hey. Guy. (It’s Mark.) Okay, Mark. If the same day is repeating over and over again, if every morning it just goes back to the beginning automatically, with everything exactly the way it was, then you could basically do whatever you want, am I right? I mean, sure, you could go to the library, but you could go to the library naked and it wouldn’t even matter, because it would all be erased the next day like a shaken Etch A Sketch. You could, I don’t know, rob a bank or hop a freight train or tell everybody what you really think of them. You could do anything you wanted.

Which was, yes, theoretically true. But honestly, in this heat, who has the energy? What I wanted was to sit on my ass somewhere air-conditioned and read books.

Plus, you know, there was always the super-slight chance that that one time it wouldn’t work, that the spell would go away as suddenly and mysteriously as it had arrived, and I would wake up on August 5th and have to deal with the consequences of whatever crazy thing I just did.

I mean, for the time being I was living without consequences. But you can’t hold back consequences forever.

* * *

Like I was saying, I went to the pool. This is important because it’s where I met Margaret, and that’s important because after I met her everything changed.

Our neighborhood pool is called Paint Rock Pool. It has a lap area and a kids’ area and a waterslide that sometimes actually works and a whole lot of deck chairs where the parents lie around sunning themselves like beached walruses. (Or walri. Why not walri? These were the kinds of things I had time to think about.) The pool itself is made out of this incredibly rough old concrete that, I’m not kidding, will take your whole skin off if you fall on it.

Seriously. I grew up here and have fallen down on it several thousand times. That shit will flay you.

The whole place is sheltered by huge pine trees, and therefore is sprinkled with pine needles and a very fine dust of canary-yellow pine pollen, which if you think about it is pine trees having sex. I try not to think about it.

I noticed Margaret because she was out of place.

I mean, first I noticed her because she didn’t look like anybody else. Most of the people who go to Paint Rock Pool are regulars from the neighborhood, but I’d never seen her before. She was tall, tall as me, five-foot-ten maybe, skinny and very pale, with a long neck and a small round face and lots of kinky black hair. She wasn’t conventionally pretty, I guess, in the sense that you would never see anybody who looked like her on TV or in a movie. But you know how there’s a certain kind of person—and it’s different for everyone—but suddenly when you see them your eye just snags on them, you get caught and you can’t look away, and you’re ten times more awake than you were a moment ago, and it’s like you’re a harp string and somebody just plucked you?

For me, Margaret was that kind of person.

And there was something else, too, even beyond that, which was that she was out of place.

Rule number one of the time loop was that everybody behaved exactly the same way every day unless I interacted with them and affected their behavior. Everybody made exactly the same choices and said and did exactly the same things. This went for inanimate objects too: Every ball bounced, every drop splashed, every coin flipped exactly the same. This probably breaks some fundamental law of quantum randomness, but hey, you can’t argue with results.

So every time I showed up at the pool at, say, two o’clock, I could count on everybody being in exactly the same place, doing exactly the same thing, every time. It was reassuring in a way. No surprises. It actually made me feel kind of powerful: I literally knew the future. I, god-emperor of the kingdom of August 4th, knew exactly what everybody was going to do before they did it!

Which was why I would have noticed Margaret anyway, even if she hadn’t been Margaret: She’d never been there before. She was a new element. Actually, the first time I saw her I couldn’t quite believe it. I thought maybe something I’d done earlier that day had set off some kind of butterfly-wing chain of events that caused this person to come to the pool when she never had before, but I couldn’t think what. I couldn’t decide whether or not to say anything to her, and by the time I decided I should, she’d already left. She wasn’t there the next day. Or the next.

After a while I let it go. I mean, I had my own life to live. Things to do. I had a lot of ice cream to eat and not get fat from. Also I had this idea that, with an infinite amount of time to play with, maybe I could find a cure for cancer, though after a few days on that I started to think maybe I didn’t have sufficient resources to cure cancer, even given an infinity of time.

Also I’m not smart enough by a factor of like a hundred. Anyway I could always come back to that one.

But when Margaret came back a second time, I wasn’t going to let her get away. By this time I’d seen the same day play out at the pool about twenty times, and it was getting a little monotonous. Heavy lies the head that wears the god-emperor’s crown. I was ready for something unexpected. Talking to strange beautiful girls is not something I excel at particularly, but this seemed important.

Anyway, if I said something stupid she’d just forget about it tomorrow.

I watched her for a while first. One of the evergreen features of August 4th at Paint Rock Pool was that every day at 2:37 one of the kids playing catch with a tennis ball massively overthrew it, so that it was not only uncatchable but also cleared the fence at the back of the pool, at which point it was essentially unrecoverable, because beyond that fence was a perilously steep and rocky gully, and then beyond that was Route 128. Nothing that went over that fence ever came back.

But not today, because along came Margaret—just casually; I would even say she was sauntering—wearing a bikini top and denim shorts and a straw sun hat, and when the kid threw she reached up on her tiptoes—flashing her even paler shaved underarm—and snagged the ball out of the air with one long skinny arm. She didn’t even look at it, just pulled it down, flipped it back into the pool, and kept walking.

It was almost like she knew what was coming too. The kid watched her go.

“Thank you,” he said, in a weirdly accurate impression of Apu from The Simpsons. “Come again!”

I saw her lips move as she walked: She said it too—“Thank you, come again”—right along with him. It was like she was reading it off the same script. She plopped down on a deck chair and reclined it all the way back, then changed her mind and hiked it back up a notch. I went over and sat down on the deck chair next to hers. Because I’m smooth like that.

“Hi.”

She turned her head, shading her eyes against the sun. Up close she was even prettier and more string-plucking than I’d thought, with a spray of freckles splashed across the bridge of her nose.

“Hi?” she said.

“Hi. I’m Mark.”

“Okay.”

Like she was granting me the point: Yes, fair enough, your name might well be Mark.

“Look, I don’t know how to put this exactly,” I said, “but would you happen to be trapped in a temporal anomaly? Like right now? Like there’s something wrong with time?”

“I know what a temporal anomaly is.”

Sunlight flashed off sapphire pool-water. People yelled.

“What I mean is—”

“I know what you mean. Yes, it’s happening to me too. The thing with the repeating days. Day.”

“Oh. Oh my God!” A massive wave of relief broke over me. I didn’t see it coming. I fell back on my deck chair and closed my eyes for a second. I think I actually laughed. “Oh my God. Oh my God. Oh my God.”

I think up until that moment I hadn’t even understood how deeply freaked out I was, and how alone with that feeling I’d been. I mean, I was having a perfectly fine time, but I was also really starting to think that I was going to be stuck forever in August 4th and that no one but me would ever know it. No one would ever believe it. Now at least somebody else would know.

Though she didn’t seem nearly as excited about it as I did. I would almost say she was a little blasé.

I bounced back up.

“I’m Mark,” I said again, forgetting that I’d already said it.

“Margaret.”

I actually shook her hand.

“It’s crazy, right? I mean, at first I couldn’t believe it. I mean can you seriously believe it?” I was babbling. “How messed up is this? Right? It’s like magic or something! Like it seriously doesn’t make any sense!”

I took a deep breath.

“Have you met anybody else who knows?”

“Nope.”

“Do you have any idea why this is happening?”

“How would I know?”

“I don’t know. I don’t know! Sorry, just a little giddy here. I’m just so, so glad you’re in this too. I mean not that I’m glad you’re trapped in time or anything, but Jesus, I thought I was the only one! Sorry. It’s going to take me a second.” Deep breath. “So what have you been doing with yourself this whole time? Besides going to the pool?”

“Watching movies, mostly. And I’m teaching myself to drive. I figure it doesn’t matter if I mess up the car because it’ll just be fixed in the morning.”

I found her hard to read. It was weird. Granted, I was hysterical, but she was the opposite. Strangely calm. It was almost like she’d been expecting me.

“Have you?” I said. “Messed up the car?”

“Yes, actually. And our mailbox. I still suck at reverse. My mom was pretty pissed off about it, but then the entire universe reset itself that night and she forgot, So. What about you?”

“Reading mostly.”

I told her about my project at the library. And about the curing cancer thing.

“Wow, I didn’t even think of that. I guess I’ve been thinking small.”

“I didn’t get very far with it.”

“Still. Points for trying.”

“Maybe I should scale it down and just go after athlete’s foot or something.”

“Or pinkeye maybe.”

“Now you’re talking.”

We sat in silence for a minute. Here we were, the last boy and girl on earth, and I couldn’t think of anything to say. I kept getting distracted by her long legs in those shorts. Her fingernails were plain, but she’d painted her toenails black.

“So you’re new, right?” I said. “Did you just move here or something?”

“Couple of months ago. We’re in that new development on Tidd Road, across the highway. Technically I think we’re not even eligible to come here, but my dad fudged it. Look, I gotta go.”

She stood up. I stood up. That was a thing I would learn about Margaret: Even with an infinity of time available, she always seemed to have to go.

“Can I have your number?” I said. “I mean, I know you don’t know me, but I feel like we should probably, you know, stay in touch. Maybe try to figure this thing out. It might go away all by itself. But then again, maybe it won’t.”

She thought about that.

“Okay. Give me your number.”

I did. She texted me back so I’d have hers. The text said it’s me.

* * *

I didn’t text Margaret for a few days. I got the impression that she liked her personal space, and that she wasn’t necessarily overjoyed at the prospect of spending forever with a person of my undeniable dorkiness. I’m not one of your self-hating nerds or anything; I’m comfortable with my place in the social universe. But I get that I’m not everybody’s idea of the perfect guy to spend an infinite amount of time with.

I lasted till four in the afternoon on day five A.M. (After Margaret).

Four o’clock was about when the repetitiveness of it all started to get to me. At the library, I watched the same old guy clump up to the circulation desk with his walker. I heard the same library flunky walk by with the same squeaky cart. The same woman with hay fever disputed a late fee while having a sneezing fit. The same four-year-old had an operatic meltdown and got dragged out of the building.

The problem was that it was all starting to seem less and less real—the endless repetition was kind of leaching the realness out of everything. Things were mattering less. It was fun to just do whatever I wanted all the time, with no responsibilities, but the thing was, the people around me were starting to seem slightly less like people with actual thoughts and feelings, which I knew they were, and slightly more like extremely lifelike robots.

So I texted Margaret. Margaret wasn’t a robot. She was real, like me. An awake person in a world of sleepwalkers.

Hey! It’s Mark. How’s it going?

It was about five minutes before she got back to me; by then I’d gone back to reading The Restaurant at the End of the Universe by Douglas Adams.

Can’t complain.

Getting dangerously bored here. You at the pool?

I was driving. Jumped the curb. Hit another mailbox.

Ow. Good thing time is busted.

Good thing.

I thought that brought things to a nice, rounded conclusion, and I wasn’t expecting anything more, but after another minute I got the three burbling dots that meant she was typing again.

You at the library?

Yup.

I’ll swing by. 10 mins.

Needless to say, this outcome greatly exceeded my expectations. I waited for her out on the front steps. She drove up in a silver VW station wagon with a scrape of orange paint on the passenger-side door.

I was so glad to see her I wanted to hug her. It took me by surprise again. It was just such a relief not to have to pretend anymore—that I didn’t know what was coming next, that it hadn’t all happened before, that I wasn’t clinging to a sense that things mattered by my absolute fingernails. Probably falling in love is always a little like that: You discover that one other person who understands what no one else seems to, which is that the world is broken and can never, ever be fixed. You can stop pretending, at least for a little while. You can both admit it, if only to each other.

Or maybe it’s not always like that. I don’t know. I’ve only done it once. Margaret got out and sat down next to me.

“Hi.”

“Hi,” I said.

“So. Read any good books lately?”

“As it happens I have, but hang on. Wait. Watch this.”

The collision happened every day, right here on this spot. I’d seen it at least five times. Guy staring at his phone versus other guy staring at his phone and walking his dog, a little dachshund. The leash catches the first guy right in the ankles and he has to windmill his arms and do a little hopping dance to keep from falling over, which gets him even more wrapped up in the leash. The dog goes nuts.

It went perfectly, the way it always did. Margaret snorted with laughter. It was the first time I’d seen her laugh.

“Does he ever actually fall over?”

“I’ve never seen it happen. Once I yelled at them—like, Watch out! Sausage dog! Incoming! And the guy looked at me like, Come on, of course I saw the guy with the dog. That would never happen in a million years. So now I just let them do it. Besides, I think the dog enjoys it.”

We watched the traffic.

“Wanna drive around for a while?” she asked.

“I don’t know.” I played hard to get. Because I’m smooth like that. “You don’t make it sound like the world’s safest activity.”

“What can I tell you? Life’s full of surprises.” Margaret was already walking to the car. “I mean, not our lives. But life generally.”

We got into the station wagon. It smelled like Margaret, only more so. We cruised past the many olde-timey shops of Lexington Center.

“Anyway,” she said, “if we die in a heap of hot screaming metal, we’ll probably just be reincarnated in the morning.”

“Probably. See, it’s the probably part that worries me.”

“Actually I’ve been thinking about that, and I’m pretty sure we’d come back. Other people do. I mean, think about how many people in the world die every day. If they didn’t all come back, then all those people would turn up dead in the morning when the world reset. Or they’d be vanished or Raptured or something. Either way, somebody would have noticed by now. Ergo, they must get resurrected.”

“And then die again. Jesus, people must be having to die over and over again. I wonder how many.”

“One hundred fifty thousand,” she said. “I looked it up. That’s how many people die every day, on average.”

I tried to picture them. A thousand people standing in a line, all marching off a cliff. And then a hundred fifty of those lines.

“God, imagine if you had a really painful death,” I said. “Or even just a really shitty day, like you’re sick and suffering. Or you get fired. Or somebody dumps you. You’d get dumped over and over again. That would be horrible. Seriously, we have to fix this.”

She didn’t seem interested in pursuing this line of inquiry. In fact, she went stone-faced when I said it, and it occurred to me for the first time to wonder whether August 4th might be not as simple a day for her as it was for me.

“Sorry, that was getting a little depressing,” I said.

“Yeah,” she said. “Probably lots of good things are happening over and over again, too.”

“That’s the spirit.”

We’d reached the edge of town. It’s not a big town. Margaret took an on-ramp onto Route 2.

“Where are we going?” I asked.

“Nowhere special.”

It was, as always, a blazing hot afternoon, and the highway was clogged with rush hour traffic.

“I used to listen to the radio,” she said, “but I’m already sick of all the songs.”

“I wonder how far this thing goes. Like, is it just Lexington that’s in the time loop, or is it the entire planet that’s stuck like this? Or is it the entire universe? Wouldn’t it have to be the entire universe? Black holes and quasars and exoplanets, all resetting themselves every day, with us in the middle of it? And we’re the only beings in the whole universe who know about it?”

“That’s kinda egocentric, don’t you think?” she said. “Probably there are a couple of aliens out there who know about it too.”

“Probably.”

“Actually I was thinking, if it is just a local thing, maybe if we went far enough we’d get outside the field or zone or whatever it is and time would go forward again.”

“It’s worth a try,” I said. “Like, just get in the station wagon and floor it and see what happens.”

“I was more thinking of getting on an airplane.”

“Right.”

Though to be honest at that moment I was enjoying just riding in Margaret’s car so much that I wasn’t sure I wanted time to start working again quite yet. I would’ve been happy to repeat these five minutes a few hundred times. She turned off the highway.

“I lied before. About where we’re going. I want to show you something.”

She turned into a sandy parking lot. Gravel crackled under the tires. I knew where we were: It was the parking lot for the Wachusett Reservoir. My dad took me here all the time when I was little and he was teaching me how to fish. It’s stocked with zillions of pumpkinseed sunfish. Though once I passed puberty I developed empathy with the fish and refused to do it anymore.

Margaret checked her watch.

“Shit. Come on, we’re going to miss it.”

She actually took off running through the thin pine woods around the reservoir. She was fast—those long legs—and I didn’t catch up with her till she stopped suddenly a few yards short of the brown sandy beach. She put a hand on my arm. It was the first time she ever touched me. I remember what she was wearing: a T-shirt, orange washed to a pale sherbet peach, with an old summer camp logo on it. Her fingers were unexpectedly cool.

“Look.”

The water was glittering with beads of molten gold in the late afternoon. The air was still, though you could hear the drone of the highway in the background.

“I don’t—”

“Wait. Here it comes.”

It came. A hawk swooped down out of the air, a dense, dangerous bundle of dark feathers. It hit the water hard, back-winged frantically for a second, spraying jeweled droplets everywhere, then beat furiously back into the sky with a flashing, wriggly pumpkinseed sunfish twisting in its claws and was gone.

The hot, dusty afternoon was as still and empty as before. The whole thing had taken maybe twenty seconds. It was the kind of thing that reminded you that a day you’d already lived through fifty times could still surprise you. Margaret turned to me.

“Well?”

“Well? That was amazing!”

“Wasn’t it?” Her smile could have stopped time all on its own. “I saw it just by chance the other day. I mean today, but you know. The other today.”

“Thank you for showing it to me. It happens every time?”

“Exactly the same time. 4:22 and thirty seconds. I’ve watched it three times already.”

“It almost makes being stuck in time worthwhile.”

“Almost.” Then she thought of something and her smile faded a little. “It almost does.”

* * *

Margaret dropped me off at the library—I’d left my bike there—and that was that. I didn’t ask her out or anything. I figured it was quite enough that she was trapped in time with me. It’s not like we could avoid each other. We were like two castaways, except instead of being stranded on a desert island we were stranded in a day.

Because I am a person of uncommon strength of will, I didn’t text her again till two days later.

Found another one. Back stairs of library—the ones in the parking lot—11:37:12.

Another what?

One. Come.

She didn’t answer, but I waited for her anyway, just in case. I didn’t have anything better to do. And she came, the boatlike station wagon heeling into the parking lot at 11:30. She parked in the shade.

“What is it?” she said. “Like another hawk?”

“Keep your voice down, I don’t want to screw it up.”

“Screw what up?”

I pointed.

The rear entrance of the library had concrete stairs leading down to the parking lot. There was nothing particularly extraordinary about the stairs, but they had that mysterious Pythagorean quality that attracts fourteen-year-old skateboarders like a magnet attracts iron filings. They flocked to it like vultures to a carcass. They probably showed up the second the concrete was dry.

“That’s the thing?” she said. “Skate rats are the thing?”

“Just watch.”

Each kid took his or her turn going down the steps, one after the other, did his or her thing, then walked back up the wheelchair ramp and got back in line. It never stopped.

“Okay,” I said. “So what do you notice about these skate rats?”

“What do you mean?” Margaret was visibly unintrigued.

“What do they all have in common?”

“That ironically, despite the fact that skateboarding defines their very identity, they all suck at it?”

“Exactly!” I said. “The iron law of skate rats the world over is that they never, ever land that one trick they’re always trying to land. Now look.”

A skateboarder rolled toward the top of the steps, knees bent, jumped, and his skateboard went clattering off at a random angle without him. Cue next skater. And the next. And the next.

I checked my watch. 11:35.

“Two more minutes,” I said. “Sorry, I figured you’d be late. How’s everything else?”

“Not bad.”

“How’s the driving?”

“Great. I need a new challenge. It’s between juggling and electrical engineering.”

“Gotta be practical. Juggling’s the future.”

“It’s the sensible choice.”

A skater went down, a potentially ugly fall, but she rolled out of it and came up fine. The next one chickened out before he even got to the top of the steps.

“Okay, two more.” Miss. “One more.” Miss. “Okay. Showtime!”

The next turn belonged to a round-faced, thick-bodied kid with a dark hair-helmet under his real helmet, whom we’d already seen muff a few tricks. His face was set and determined. He pushed off, found his balance, set his feet, crouched down, hit the steps, and jumped.

His board flipped once, then came down hard on the railing in a perfect grind. Seriously, it was like in a video game—this was like X Games–level shit. The kid grinded all the way down the rail, ten feet in one long second, arms out wide. The first time I saw it I figured that was it. He’d nailed the trick, that was enough; his name would live in song and story forever. But no, it wasn’t enough. He had to go for all the glory: a full 360 flip out of the grind.

With an athleticism that seemed to have nothing to do with his pale, doughy physique, he popped off the rail and into the air, levitating while his board spun wildly along both axes. Then wham!—he stomped down on it, both feet. And he stuck it.

He stuck it! The board bowed so deeply it looked like it was going to snap, but he kept his feet, and as he straightened up … his face! He couldn’t believe it! He made the happiest face that it is anatomically possible for a human to make.

“Oh my God!” He held up both fists. “Oh my fucking God!”

The rats came pouring down the steps. They mobbed him. It was, and might quite possibly always be, the greatest moment of his life.

“Tell me that wasn’t worth it,” I said.

Margaret nodded solemnly. She was looking at me differently than she had before. She seemed to be seeing me, really paying attention to me, for the first time.

“It was worth it. You were right. It was a perfect thing.”

“Like the hawk.”

“Like the hawk. Come on, let’s go get something expensive and bad for us for lunch.”

We got the most brutally fattening thing we could find, which was bacon cheeseburgers—extra bacon, extra cheese. That was the day we came up with the idea for the map of tiny perfect things.

* * *

It’s tough getting through daily life, finding stuff that doesn’t suck to take pleasure in—and that’s in normal life, where every twenty-four hours you get a whole fresh new day to work with. We were in a tougher situation, because we had to make do with the same day every single day, and that day was getting worn pretty thin.

So we got serious about it. The hawk and the skate rat were just the beginning. Our goal was to find every single moment of beauty, every tiny perfect thing, that this particular August 4th had to offer. There had to be more: Moments when, for just a few seconds, the dull coal of reality was compressed by random chance into a glittering diamond of awesomeness. If we were going to stay sane, we were going to have to find them all. We were going to have to mine August 4th for every bit of perfection it had.

“We have to be super-observant,” Margaret said. “Stay in the moment. We can’t just be alive, we have to be super-alive.”

In addition to being super-alive we were going to be organized. We bought a snazzy fountain pen and a big foldy survey map of Lexington and spread it out on a table in the library. Margaret found the spot on the Wachusett Reservoir and wrote “HAWK” and “16:32:30” on it in snazzy purple ink. (Military time made it seem that much more official.) On the spot marking the rear steps of the library, I wrote “11:37:12” and “SKATE RAT.”

We stepped back to admire our work. It was a start. We were a team: Mark and Margaret against the world.

“You realize that when the world resets in the morning the whole map’s going to be erased,” she said.

“We’ll have to remember it. Draw it again from scratch every day.”

“How do you think we should go looking for them? The perfect things?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “Just keep our eyes open, I guess.”

“Live in the now.”

“Just because it’s a cliché doesn’t mean it’s not true.”

“Maybe we can work in sectors,” she said. “Like divide the town into a grid, then divide the squares of the grid between the two of us, then make sure we’ve observed each square at every moment in the twenty-four-hour cycle, so we don’t miss anything.”

“Or we could just walk around.”

“That’s good too.”

“You know what this reminds me of?” I said. “That map in Time Bandits.”

“Okay. I have no idea what that means.”

“Oh my God! If the universe stopped just so I could make you watch Time Bandits, then I think it’s all worth it.”

Then I started trying to explain to her what it said in Flatland about the fourth dimension, but it turned out I was totally mansplaining, because not only had she already read Flatland but also, unlike me, she actually understood it. So she explained it to me.

“We’re three-dimensional, right?”

“I’m with you so far.”

“Now look at our shadows,” she said. “Our shadows are flat. Two-dimensional. They’re one dimension down from us, just like in a flat universe the shadow of a two-dimensional being would be a one-dimensional line. Shadows always have one fewer dimensions than the thing that cast them.”

“Still with you. I think.”

“So if you want to imagine the fourth dimension, just imagine something that would cast a three-dimensional shadow. We’re like the shadows of four-dimensional beings.”

“Oh wow.” My flat little mind, like the Square’s, was getting blown. “I thought the fourth dimension was supposed to be time or something.”

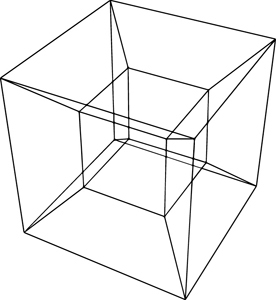

“Yeah, that turned out to be a made-up idea. They’ve even worked out what a three-dimensional representation of a four-dimensional cube might look like. It’s called a hypercube. Here, I’ll draw one for you. Although with the caveat that my drawing will be merely two-dimensional.”

I accepted this caveat. She drew it. It looked like this:

I stared at the drawing for a long time. It didn’t look all that four-dimensional, though I guess how would I know?

“Do you think,” I said, “that this whole time loop was somehow created by superior four-dimensional beings with the power to manipulate the fabric of three-dimensional space-time itself? That they folded our entire universe into a loop as easily as we would make a Möbius strip out of a piece of paper?”

She pursed her lips. She took the idea more seriously than it probably deserved.

“I’d be a little disappointed if it was,” she said finally. “You’d think they’d have something better to do.”

* * *

She texted me two days later.

Corner of Heston and Grand, 7:27:55.

I got there at 7:20 the next morning, with coffee. She was already there.

“You’re up early,” I said.

“Didn’t sleep. I wanted to see if anything weird happened in the middle of the night.”

“Weird like what?”

“You know. I wanted to be awake when the world rolls back.”

The crazy thing was, I had never even tried that. I had always slept through it. I guess I’m more of a morning person.

“What’s it like?”

“It’s the weirdest thing ever. Every day has to start exactly the same way, so if you woke up in your bed on August 4th—which I’m assuming you did, unless I’m severely underestimating you—”

“You’re not underestimating me.”

“So if you woke up in bed the first time, you have to wake up in your bed all the other times too, so that the day starts exactly the same way every time. Which means that if you’re not in bed at midnight, it puts you to bed. One second I was sitting on the floor dicking around with my phone, the next the lights were off and I was under the covers. It’s like there’s some invisible cosmic nanny who grabs you and tucks you in.”

“That really is the weirdest thing ever,” I said.

“Plus, when you hit midnight, the date on your phone doesn’t change.”

“Right.”

“I guess that part’s not that weird.”

“So what are we looking for here?”

“I don’t want to spoil it,” she said. “I think that should be part of the rules. You have to see it fresh.”

Heston and Grand was a busy intersection, or busy enough that it had a stoplight. It was weird to see rush hour traffic—everybody heading off to work, so urgent and focused, mocha Frappuccino in the cup holder, to do all the stuff they’d already done yesterday, which would get undone again at midnight. To make all the money they would unknowingly give back overnight.

7:26.

“I don’t know why I feel nervous,” she said. “I mean, it pretty much automatically has to happen.”

“It’s going to happen. Whatever it is.”

“Okay, watch for the break in traffic. Here we go.”

Lights changed somewhere upstream, and the road emptied out. A lone black Prius turned off a side street and rolled up at the red light right in front of us.

“Is that it?”

“Yup. Look who’s driving.”

I squinted at it. The driver did look weirdly familiar.

“Wait. That’s not…?”

“I’m pretty sure it is.”

“It’s whatshisname, Harvey Dent from The Dark Knight!”

“No,” she said patiently, “it’s not Aaron Eckhart.”

“Wait. I can get this.” I snapped my fingers a couple of times. “It’s that guy who gets his head cut off in Game of Thrones!”

“Yes!”

It was Sean Bean. Actual Sean Bean, the actor. Realizing he’d been spotted, he gave us his trademark rueful, lopsided grin and a half-wave. Then the light changed and he rolled on.

We watched him go.

“Weird to see him with his head back on,” I said.

“I know. But so, what do you think?”

“I liked him better as the guy who threw up in Ronin.”

“I mean what do you think? Is it mapworthy?”

“Oh, definitely. Let’s map it.”

We went back to her house to redraw the map and watch Time Bandits, which she still hadn’t seen. Her parents weren’t there; her mom had left for a business trip that morning, and her dad was always away at the same yoga retreat, forever.

But she was exhausted from having stayed up all night, and she fell asleep on the couch five minutes in, before the dwarfs even show up. Before the little boy even realizes that the world he lives in is magic.

* * *

It was like a big Easter egg hunt. Margaret got the next one, too: a little girl who made one of those enormous soap bubbles, the kind you make with two sticks and a loop of string, that always pop after like two seconds, only this one didn’t. It was huge, approximately the same size as she was, and it drifted low over Lexington Green, undulating like a weird, translucent ghost amoeba, farther and farther, past where you could even believe it hadn’t popped yet, before it finally crossed a sidewalk and met its end on a parked car.

I found another one two days later: a single cloud, alone in the sky, that for about a minute, seen from the corner of Hancock and Greene, looked exactly like a question mark. But I mean exactly. Like someone had typed it in the sky.

A full five days later she saw two cars pulled up next to each other at a light. License plates: 997 WON and DER 799. The next day I found a four-leaf clover in a field behind my old elementary school, but we disallowed it. Not moment-y enough somehow. Didn’t count.

That night, though, about eight o’clock, I was biking the streets at random when I saw a woman walking by herself. Thirtyish, heavyset, dressed like a receptionist at a real estate agency. Somebody must have texted her, because she looked at her phone and stopped dead. For a terrible second she squatted down and covered her eyes with one hand, like the news had hit her in the stomach so hard she could barely stand.

But then she straightened up again, raised a fist in the air, and ran off into the night singing “Eye of the Tiger” at the top of her lungs. Good voice, too. I never found out what the text was, but it didn’t matter.

That one was fragile: The first time I tried to show it to Margaret we ended up distracting the woman and she didn’t even notice the text. The second time she got the text but apparently didn’t want to sing “Eye of the Tiger” in front of us. In the end, we had to hide behind a hedge for Margaret to get the full effect.

We wrote them all down. CAT ON TIRE SWING (10:24:24). SCRABBLE (14:01:55)—some guy playing in the park made quixotic on a triple word score. LITTLE BOY SMILING (17:11:55)—he’s just sitting there smiling about something; you kind of had to be there.

It wasn’t all about the perfect things. We did other things, too, that had nothing to do with any of this stuff. We had contests: Who could come up with the most cash in one day without actually taking it out of the bank. (I could, by selling my mom’s car on Craigslist while she was at work. Sorry, Mom!) Who could acquire the best new skill that we’d never tried before even once. (I won that one, too. I played “Auld Lang Syne” very badly on the saxophone; she spent the day trying and increasingly furiously failing to ride a unicycle.) Who could get on TV. (She won by talking her way into the local news station, posing as a summer intern, and then “accidentally” walking on set while they were live. They got so many e-mails from people who enjoyed her cameo that by the end of the day they’d offered her an actual internship. That was Margaret for you.)

I couldn’t have cared less who won. With all apologies to the rest of humanity who were forced to repeat August 4th over and over again like so many lifelike animatronic automatons, being stuck in time with Margaret was better than any real time I’d ever had in my life. I was like the Square in Flatland: I had finally met a Sphere, and for the first time in my life I was looking up and seeing what a crazy, enormous, beautiful world I’d been living in without even knowing it.

And Margaret was enjoying it, too, I knew she was. But it was different for her, because as time passed—I mean, it didn’t, but you know what I’m saying—I began to wonder if there was something else going on in her life, too, something she didn’t talk about and that I didn’t know how to ask her about. You could see it in little things she did or didn’t do. She checked her phone a lot. At odd moments her eyes went distant, and she got distracted. She always left a bit early. When I was with her, I was only ever thinking about her, but it wasn’t like that for Margaret. Her world was more complicated than that.

We finally watched Time Bandits, anyway. It holds up pretty well, though I don’t think she liked it as much as I did. Maybe you have to see it as a kid, the first time. But she liked Sean Connery.

“Apparently it said in the script, ‘This character looks just like Sean Connery but a lot cheaper,’” I said. “And then Sean Connery read the script and called them up and said, ‘Let’s do it.’”

“That must have been a perfect moment. But I don’t get why he comes back at the—”

“Stop! Nobody knows! It’s one of the great mysteries of the universe! Forbidden knowledge. We shouldn’t even be talking about it.”

We were on the foam couch in her family’s rec room, which had a thinly carpeted concrete floor and one glass wall that looked out at a big backyard.

I’d spent most of the previous hour inching imperceptibly sideways on the couch, nanometer by nanometer, and then subtly shifting my weight so that my shoulder rested against hers and we were sort of leaning against each other. It felt like some cool sparkly energy was flowing out of her and into me and lighting me up from the inside. I felt like I was glowing. Like we were glowing.

I don’t think anybody in the history of cinema has ever enjoyed a movie as much as I enjoyed Time Bandits that night. Roger Ebert watching Casablanca could not have enjoyed it one-tenth as much.

“Margaret, can I ask you something?” I said.

“Of course.”

“Do you ever miss your parents? I mean, I can hang out with mine pretty much whenever I want—and anyway, where my parents are concerned, a little of that goes a long way. But you hardly see yours at all. That’s got to be hard.”

She nodded, looking down at her lap.

“Yeah. That’s kind of hard.”

Her corkscrewy hair fell down over her face. It reminded me of double helices, of DNA, and I thought about how, somewhere inside them, there were tiny corkscrew-shaped molecules containing the magic formula for how to make corkscrewy hair. How to make Margaret.

“Do you want to go find them? I mean, we could probably track them down inside of twenty-four hours. Hit that yoga retreat.”

“Forget it.” She shook her head, not looking at me. “Forget it. We don’t have to.”

“I know we don’t have to, I just thought…”

She still wasn’t looking at me. I’d hit some kind of a nerve, a raw one that led off somewhere that I didn’t quite understand. It hurt me a bit that she wouldn’t or couldn’t say where. But she didn’t owe me any explanations.

“Sure. Okay. I just wish you’d gotten a better day, that’s all. I don’t know who it was that chose this day, but I question their taste in days.”

She half smiled; literally, one half of her mouth smiled and the other didn’t.

“Somebody has to have bad days,” she said. “I mean statistically. Or the bell curve would get all messed up. I’m just doing my part here.”

She took my hand—she picked it up off my lap in both of hers and sort of it squeezed it. I squeezed her hand back, trying to keep breathing normally while my heart blew up inside me a hundred times. Everything went still, and I almost think something might have happened—like that might have been the moment—except that I immediately blew it.

“Listen,” I said, “I had an idea for something we could try.”

“Does it involve unicycling? Because I’m telling you, I never want to see another of those one-wheeled devil-cycles in my life.”

“I don’t think so.” I kept waiting for her to put my hand down, but she didn’t. “You remember you had that idea once, where we travel as far as we can and see if we can get outside the zone where the time loop is happening? I mean, assuming it’s limited to a zone?”

She didn’t answer right away, just kept looking out at her backyard, which was getting darker and darker in the summer twilight.

“Margaret? Are you okay?”

“No, right, I remember.” She let go of my hand. “It’s a good plan. We should do it. Where should we go?”

“I don’t know. I don’t think it matters that much. I figure we should just head straight to the airport and get on the longest flight we can find. Tokyo or Sydney or something. But you’re sure you’re okay?”

“Absolutely. Absolutely okay.”

“We don’t have to. It probably won’t work. I just thought we should try everything.”

“We absolutely should. Everything. Definitely. Let’s not do it tomorrow, though.”

“No problem.

“Day after, maybe.”

“Whenever you’re ready.”

She nodded, three quick nods, as if she’d made up her mind.

“The day after tomorrow.”

* * *

We couldn’t start out before midnight, because of the cosmic nanny effect, but we agreed that at the stroke of midnight we would both leap out of bed and she would immediately book us flights on Turkish Airlines to Tokyo, leaving Logan Airport at 3:50 a.m., which was the earliest flight to somewhere really far away that we could find. Margaret had to be the one to do it because she had a debit card, because she had a joint bank account with her parents, which I didn’t. I promised I would hit her back if it worked.

Then I snuck out into the warm, grassy-smelling night to wait and be attacked by numberless mosquitoes. There was no moon; August 4th was a new moon. Margaret came rolling up with the lights off.

It felt close and intimate, being in her car with her in the middle of the night. In fact it was the most boyfriendy I’d ever felt with Margaret, and even though I was not in actual fact her boyfriend, it was a thrilling feeling. We didn’t talk till we were cruising along the empty highway, surfing the rolling hills on the way into Boston, under the indifferent, insipid orange gaze of the sodium streetlights.

“If this works, my parents are going to think we ran away together,” she said.

“I didn’t even think about that. I left mine a note saying I caught the bus into Boston for the day.”

“I’m just picturing my dad saying over and over that it’s okay if I’m pregnant, he totally understands, he just wants to talk about it.”

“The Tokyo thing’s going to be the weirdest part. Like, where did that come from?”

“I’m going to say it was your idea,” Margaret said. “You were tired of reading imported manga; you wanted to go straight to the source.”

“It’s cool that you’re so supportive of my enthusiasms.”

We were joking, but I knew—really knew right then—that I was in love with Margaret. I wasn’t joking, I was completely serious. I would have run away to Tokyo with her anyway, like a shot, for no reason at all. But I told myself I wasn’t going to say anything, I wasn’t going to do anything about it, till the time thing was fixed. I didn’t want her to feel like she was stuck with me. I wanted it to count.

Also, yeah, I was terrified. I had never been in love before. I had never wagered this much of my heart before. As badly as I wanted to win, I was even more scared of losing.

Gazing out the car window at the black trees against the light-pollution-gray sky, I thought about how much I would miss August 4th, our day, if this worked. Mark and Margaret Day. The pool, the library, the tiny perfect things. Maybe this was crazy. After all, I had time and I had love. I had it all, I had everything, and I was throwing it away, and for what? For real life? For getting old and dying like everybody else?

But yeah: everybody else. Everybody in the world who wasn’t getting to live their lives. They were getting robbed of everything, every day. My parents, getting up day after day after day and doing the exact same things, over and over again. Having their stupid fight about the car. My sister practicing her Vivaldi and never getting any better. Did it matter, if they didn’t know it? I wanted to think that maybe it didn’t. But I knew that it did.

And I knew that, deep down, I’d had enough of living without consequences too. Low-stakes living, where nothing mattered and all your wounds healed over the next morning, no scars. I needed something more. I was ready to go back to real life. I was ready to go anywhere, if it was with Margaret.

And it would be good to see the moon again.

This late at night the airport was almost empty. We collected our tickets from the kiosks and wandered through security. No lines. 3:50 a.m. is the only time to fly. We had no luggage so we breezed through security and just sat at the gate and waited. Margaret didn’t feel much like talking, but she rested her head on my shoulder. She was tired, she said. And she didn’t like flying.

After a while I went off to find us some Diet Cokes. They called our flight. We shuffled down the jetway with a lot of other tired, disheveled-looking people.

We’d gotten seats together. Margaret seemed more and more out of it, sunk inside herself, staring at the seat back in front of her. She felt far away even though we were sitting right next to each other.

“Are you worried about flying?” I asked. “Because, you know, even if we crash we’ve still got the whole reincarnation thing going. And anyway, if a plane crashed on August 4th we would’ve heard about it by now.”

“Don’t jinx it.”

“You know, in a way I hope this doesn’t work, because if it does we’re going to be out a ton of money. Did you book round-trip?”

I was babbling, like I did the day we met.

“I didn’t even think about that,” she said. “Though, on the bonus side, if it works we’ll have saved the world.”

“At least there’s that.”

I closed my eyes. My numberless mosquito bites itched. We hadn’t had a lot of sleep. I liked the idea of falling asleep next to Margaret.

“Though, what if,” I said, eyes still closed, “what if the world is going to end on August 5th? What if that’s what’s happening here? What if somebody made time start repeating exactly because the world was about to get hit by an asteroid or something, and that person had, in effect, saved the world by stopping time forever—albeit at a terrible cost—and if we break the time loop, then actually we’ll be dooming the Earth to certain destruction?”

She didn’t answer. It was a rhetorical question anyway. When I opened my eyes again some Turkish flight attendants were closing the doors. It took me a second to realize that Margaret wasn’t in her seat anymore. I thought she must have gone to the bathroom, and I even got up to check on her, but I was immediately herded back to my seat by concerned Turkish Airlines employees.

After five minutes I had to admit it to myself: Margaret was no longer on the plane. She must have run out just as the door was closing.

My phone chimed.

I’m sorry Mark but I just can’t I’m sorry

Can’t what? Fly to Tokyo? Fly to Tokyo with me? Leave the time loop? What? I started texting her back, but a Turkish flight attendant told me to please turn off all phones and portable devices or switch them to airline mode. She said it again in Turkish, for emphasis. I shut down my phone.

We taxied to the runway and took off. It was a long flight to Tokyo—fourteen hours. I watched Edge of Tomorrow three times.

* * *

After all that, it didn’t work. I waited in the gate area at Narita—which looks surprisingly similar to all other airports everywhere, except that everything’s in Japanese and the vending machines are more futuristic—until it was midnight in Massachusetts and the cosmic nanny reached out from halfway around the world and put me to bed, back in my house.

When I woke up that morning, I texted Margaret, but she didn’t text me back. She didn’t text me back the next day, either. I called her, but she didn’t answer.

I didn’t know what to think, except that she didn’t want the time loop to end and, whatever the reason was, it had nothing to do with me. My entire world was just the little bubble I shared with her, but her world was bigger than that. Maybe she had someone else, was all I could think of, because of course everything had to be about me. There was somebody else and she didn’t want to leave them behind. To me our life together was a perfect thing, and I couldn’t imagine wanting anything else. But she could.

It hurt. I’d had one glorious glimpse of the third dimension, and now I was banished back to flatness forever.

For the first time I wished I was one of the normal people, the zombies, who forgot everything every morning and just went about their business as if it was all fresh and new and for the first time. Let me go, I thought at the cosmic nanny. Let me forget. Let me be one of them. I don’t want to be one of us anymore. I want to be a robot. But I couldn’t forget.

I went back to my old routine, back to the library. I still had two more Hitchhiker’s Guide books to go, and I was nowhere even near done with the A section—I still had Lloyd Alexander and Piers Anthony to go, and beyond them the great desert of Isaac Asimov stretched out into the distance. I spent all day there, except that I went outside at 11:37:12 to watch the skateboarder nail his combo.

In fact I got into the habit of checking in with a couple of our tiny perfect moments every day, which was easy because, obviously, we had a handy map of them. Sometimes I redrew it; sometimes I just went by memory. I watched the hawk score its fish. I waved to Sean Bean at the corner of Heston and Grand. I watched the little girl make her huge bubble. I always hoped I’d see Margaret at one of them, but I never did. I went anyway. It helped me feel sad, which is maybe part of the process of falling out of love, which it was obviously time for me to do. I was getting good at feeling sad.

Or maybe I was just wallowing in self-pity. It’s a fine line.

I did catch a glimpse of Margaret once, by chance. I knew it would happen sooner or later; it was only a matter of time (or lack thereof). I was driving through the center, on my way to see the Scrabble game, when I spotted a silver VW station wagon turning a corner a block away. The classy and respectful thing to do would have been to let her go, because she obviously wanted nothing to do with me, but I didn’t do the classy thing. I did the other thing. I floored it and made the corner in time to see her turning right on Concord Avenue. I floored it again. Follow that car.

I followed her out to Route 2 and along it as far as Emerson Hospital.

I’d never known Margaret to go to the hospital. She’d never talked about it. It freaked me out a bit. My insides went cold, and the closer we got, the colder they got. I couldn’t believe what a stupid jealous bastard I’d been. Maybe Margaret was sick—maybe she’d been sick this whole time and just didn’t want to tell me. She didn’t want to burden me with it. Oh my God, maybe she had cancer! I should have stuck with trying to cure it! Maybe that was the whole point of this whole thing—Margaret has some rare disease, but then we work together, and because we have the repeating-days thing we have all the time we need, and finally we come up with a cure for it and save her and she falls in love with me …

But no; that wasn’t this story. This was a different kind of story.

I waited till she was on her way in, then I parked and got out and followed her. Listen, I know I was being a prying asshole, it’s just that I couldn’t stop myself. Please don’t let her be sick, I thought. She doesn’t have to talk to me, she can ignore me for the rest of eternity, she just has to not be sick.

The lobby was hushed and businesslike. Margaret was nowhere to be seen. I read the signs next to the elevator: Radiology, Surgery, Birthing, Bone and Joint Center, Wound Care … After weeks of timelessness it was strange to be here, where so much of time’s damage and destruction ends up. There’s nowhere less timeless than a hospital.

I tried them all. I finally found her in Cancer.

I didn’t speak to her, I just watched. She was sitting on a bench, knee to knee with a woman in a wheelchair who was way too young to look as old as she did. Bald and desperately thin, she was crumpled in a corner of the chair like an empty dress, her head drooping, half awake. Margaret was bent forward, speaking softly to her, though I couldn’t tell if the woman was awake or not, with both her gray, thin hands in Margaret’s young, vital ones.

It wasn’t Margaret, it was her mother. She wasn’t on a business trip. She was dying.

* * *

I drove home slowly. I knew I shouldn’t have followed Margaret to the hospital, that I had no business intruding on her private tragedy, but at least now I understood. It made sense of everything: Why Margaret always had somewhere else to be. Why she was so distracted. Why she didn’t want to escape the time loop. The time loop was the only reason her mother was still alive.

I still didn’t understand why Margaret had kept it a secret, but that didn’t really matter. This wasn’t about me. I thought I was the hero of this story, or at least the second lead, but I was nowhere near it. I was just a bit player. I was singing in the chorus.

I didn’t know what to do with myself, so I stopped in the center of town and bought a map and went home and filled it out. I looked over the tiny perfect things to see what was left. Too late for BOUNCY BALL (09:44:56). Too late for CONSTRUCTION SITE (10:10:34). Still time for REVOLVING DOOR (17:34:19). And good old SHOOTING STAR (21:17:01).

I realized it had been a while since I saw a new perfect thing. Somewhere along the way I’d stopped looking for them. I wasn’t super-alive anymore. I’d stopped living in the now. I’d dropped back into the then.

But what was even the point? Suddenly it all seemed kind of silly. Perfect moments, what did they even mean? They were blind luck, that was all. Coincidences. Statistical anomalies. I did some Googling and it turned out somebody had actually bothered to do the math on this, a real actual Cambridge University mathematician named John Littlewood (1885–1977; thank you, Wikipedia). He proposed that if you define a miracle as something with a probability of one in a million, and if you’re paying close attention to the world around you eight hours a day, every day, and little things happen around you at a rate of one per second, then you’d observe about thirty thousand things every day, which means about a million things a month. So, on average, you should witness one miracle every month (or every thirty-three-and-one-third days, if we’re being strictly accurate). It’s called Littlewood’s law.

So there you have it, a miracle a month. They’re not even that special. I stared at the map anyway, giving particular staring attention to the ones that Margaret had found, such is love. And I did love her. It made it better to understand why she couldn’t possibly love me, not now, probably not ever, but I’m not going to pretend it didn’t hurt.

The perfect moments were surprisingly evenly distributed. There were fewer of them in the nighttime, because nothing was happening and we weren’t really looking anyway, but the rest of the day was evenly filled. There was only one bare patch in the schedule, right around dawn—a bald spot where statistically you would’ve expected a perfect moment, but we’d never found it.

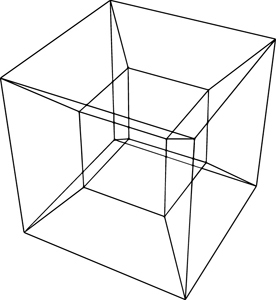

The longer I stared at the map, the more it looked like there was a pattern in it. I played a game with myself: Pretend that the points on the map were stars in a constellation. What did it look like? Look, no one should ever have to apologize for doing stupid things when the person they love has walked out of their life and they have way too much time on their hands. And I had an eternity of time. I sketched in lines between them. Maybe I could make—what? Her name? Her face? Our initials intertwined in a beautiful romantic love knot?

Nope. When I’d connected all the dots they looked like this:

Except not quite. There was one dot missing, down in the lower left corner.

I stared at it, and a funny idea struck me: What if you could use the map not just to remember when and where perfect things happened, but to predict when and where they were going to happen? It was a stupid idea, a terrible idea, but I sketched it in with a ruler anyway. The missing dot was right on top of Blue Nun Hill, which I happened to know well because it made an excellent sledding hill in winter, which at this rate it would never be again. Something should really be happening there, and judging by the rest of the schedule, it should be happening right around dawn.

The sun rose at 5:39 a.m. on August 4th, I happened to know. I waited until time flipped at midnight, then I set my alarm for five, to wake up in time for the last tiny perfect thing of them all.

* * *

I drove over to Blue Nun Hill in the warm summer darkness. The streets were deserted, the streetlights still on, houses all full of sleeping people resting up so they’d be bright-eyed and bushy-tailed and ready to sleepwalk through another day. It was still full night, not even a hint of blue on the horizon yet. I parked at the bottom of the hill.

I wasn’t the only one up. There was a silver station wagon parked there too.

I have never actually seen a Marine or any member of the armed forces take a hill, but I’m telling you, I’m pretty confident that I took that hill like a Marine. There was a big boulder at the top, dropped there casually by a passing glacier ten thousand years ago, during the Ice Age, and Margaret was sitting on it, knees drawn up to her chin, looking out at the darkened town.

She heard me coming because I was doing a lot of un-Marine-like gasping and wheezing after running all the way up the hill.

“Hi, Mark,” she said.

“Margaret,” I said, when I could sort of talk. “Hi. It’s good. To see you.”

“It’s good to see you too.”

“Is it all right if I join you?”

She patted the rock beside her. I boosted myself up. The hill faced east, and the horizon was now glowing a deep, intense azure. We didn’t talk for a while, but it wasn’t awkward. We were just getting ready to talk, that was all.

“I’m sorry I disappeared like that,” she said.

“It’s okay,” I said. “You’re allowed to disappear.”

“No, I should explain.”

“You don’t have to.”

“But I want to.”

“Okay. But before you do, I have a confession to make.”

I told her how I’d followed her to the hospital and spied on her with her mother. It sounded even worse when I said it out loud.

“Oh.” She thought about it. “No, I get it. I probably would’ve done the same thing. Kind of creepy, though.”

“I know. It felt that way even at the time, but I couldn’t stop myself. Listen, I’m just really sorry. About your mom.”

“It’s okay.”

But she choked on that last word, and her face crumpled, and she crushed her forehead into her knees. Her shoulders shook silently. I rubbed her back. I wished more than anything that I could spend all of my monthly one-in-a-million miracles at once, forever, to make her sadness go away. But things don’t work like that.

“Margaret, I’m so sorry. I’m so sorry. I’m so sorry.”

Birds were twittering joyfully now, tactlessly, all around us. She busily wiped away tears with the back of her wrist.

“There’s something else I have to explain,” she said. “The day before this whole thing started I went to see my mother at the hospital, and the doctors told me they were stopping treatment. There was no point—”

She squeaked that last word, and the sadness strangled her again, and she couldn’t go on. I put my arm around her shoulders and she sobbed on my neck. I breathed in the smell of her hair. She felt so thin and precious, to have all that grief inside her. She’d had it this whole time, all by herself. I wished I could take it from her, but I knew I couldn’t. It was her grief. Only she could carry it.

“When I went to bed that night, all I could think was that I wasn’t ready.” She swallowed. Her eyes were still red, but they were dry now, and her voice was steady. “I wasn’t ready to let go. I’m only sixteen, I wasn’t ready to not have a mom. I needed her so much.

“That night, when I went to bed, all I could think was that tomorrow cannot come. Time cannot go on. I am pulling the emergency brake of time. I even said it out loud: ‘Tomorrow cannot come.’

“And when I woke up that morning, it was true. It was the same day again. Time had stopped for me. I don’t know why; I guess it just didn’t have the heart to keep going. Somebody somewhere decided that I needed more time with her. That’s why I ran off that plane to Tokyo. I was afraid it would work, and I wasn’t ready.”

We were silent for a long time after that, while I thought about the love inside Margaret, how much of it there must have been that even time couldn’t stand up to it. There were no fourth-dimensional beings. It was Margaret’s heart, that was all. It was so strong it bent space-time around it.

“But I knew there was a catch. I always knew it. The catch was that if I fell in love, it would end. Time would roll forward again, like it always does, and it would take my mom along with it. I don’t know how, but I knew that was always the deal. When I could fall in love with someone, that’s how I would know it was time to say good-bye to her for real.

“I think that’s why you’re here. For me to fall in love with. That’s why you got sucked into this. I knew it as soon as I saw you.”

The sun was almost up, the sky was getting bright, and it was like I could feel a sun rising inside me, too, bright and warm, filling my whole self with love. Because Margaret did love me. And at the same time I was crying—the sadness didn’t go away, not in the slightest. I was happy and sad, both at once. I thought about what time is, how we’re being broken every second, we’re losing moments all the time, leaking them away like a stuffed animal losing its stuffing, until one day they’re all gone and we lose everything. Forever. And then, at the same time, we’re gaining seconds, moment after moment. Every one is a gift, until at the end of our lives we’re sitting on a rich hoard of moments. Rich beyond imagining. Time was both those things at once.

I took both Margaret’s hands in mine.

“Is it time? Is this the last day?”

She nodded solemnly.

“It’s the last one. The last August 4th. I mean, till next year anyway.” Tears were streaming down her cheeks again, but she smiled through them. “I’m ready now. It’s time.”

The sun cracked the edge of the world and began to rise.

“You know what’s funny though?” she said. “I keep waiting for the thing to happen. You know, the perfect thing, the last one. The way it’s supposed to on the map. But maybe we missed it while we were talking.”

“I don’t think we missed it.”

I kissed her. You can spend your life waiting and watching for perfect moments, but sometimes you have to make one happen.

After a few seconds, the best seconds of my life so far, Margaret pulled away.

“Hang on,” she said. “I don’t think that was it.”

“It wasn’t?”

“It wasn’t perfect. I had a hair in my mouth.”

She swept her hair to one side.

“Okay, kiss me again.”

I did. And this time it was perfect.