POSTSCRIPT: SKYSCRAPER

The writers of our generation... had one privilege: to write a poem in which all was but order and beauty, a poem rising like a clean tower.

Malcolm Cowley, Exile’s Return, 1934

To many, modernist America took its characteristic form in the “tower” skyscraper, an urban machine-structure that became a fact of life throughout the United States by the early 1920s. Before the turn of the century Frank Lloyd Wright had proposed a ten-story building of structural steel covered with translucent panels, and in the early 1920s he designed a skyscraper resembling a scaled-up version of his prairie-style houses in the suburban Chicago village of Oak Park. The village reference is not amiss. The title character of Sinclair Lewis’s novel, Babbitt, spends his workdays in an “austere tower of steel and cement and limestone ... as fireproof as a rock and as efficient as a typewriter.” The skyscraper, says the novelist, is the new American Main Street, and its inhabitants now live in a vertical village (Babbitt 5, 29, 30).

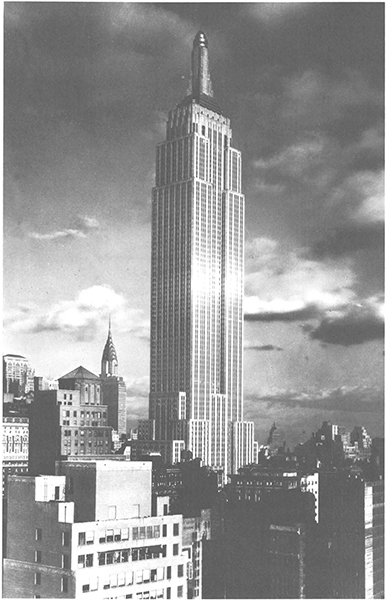

The so-called village objectified the new values of a culture shifting gears, for the skyscraper enacted the twentieth-century traits of functionalism, efficiency, and speed. Closely identified with New York City, the skyscraper gave rise to such landmarks as Manhattan’s American Radiator Building (1924) and the Chrysler Building (1930) with its white brick tower and stainless-steel arches. The passion for skyscraper height was best instanced in the Empire State Building (1931), which rose 102 stories and 1,250 feet. In the 1980s one architectural critic calls it “an immensely skillful piece of massing—a five-story base, filling out the full site, above which rises a tower with its mass correctly broken by indentations running the full height, and topped off by a crown of setbacks culminating in a gently rounded tower” (Goldberger 49, 58, 84-86). In the early 1930s so politically trenchant a critic as Edmund Wilson conceded, “There is no question that the new Empire State Building is the handsomest skyscraper in New York” (American Earthquake 292).

The classic setback skyscraper is the appropriate form with which to conclude this discussion. Visual and kinetic, paradoxically static and soaring, the skyscraper has direct connections with the poems and fiction of Dos Passos, Hemingway, and Williams. In crucial ways their texts did enact the values of what Malcolm Cowley called a “clean tower” of modernist poetic privilege. Of course, none of these writers wrote much about skyscrapers, not even Dos Passos, whose fiction centered in New York City, or Williams, who saw the skyscraper as a modern candy box (“skyscrapers / filled with nut chocolates” [I 99]). Once again, the issue is not mere representation, even though the skyscraper has long lent itself to pictorial treatment.

William F. Lamb, The Empire State Building, photograph by Irving Browning, 1931 (Courtesy New-York Historical Society)

The connection between literature and skyscraper arises from shared design values. John Dos Passos, for instance, wanted to grasp the life of a modern population within a structure, the novel. He built volume after volume, stopping U.S.A. when it became a trilogy—stopping, but not ending. Implicitly the novel-building by the self-styled “architect of history” could go on and on, just as the skyscraper continues its setback masses and invites the eye to see its movement of vertical line beyond its point of termination. Dos Passos’s fiction ever pushes for greater length, more windows on contemporary culture, more stories and storeys moving through time and space toward the future.

That swift movement of the eye along the flush planes and vertical thrusts of the skyscraper has implications for literary style. It calls to mind the Hemingway sentence, a direct statement proceeding without digression or qualification. It is the architectural equivalent of the straight line without curves, the column without entablature. “The trunks were straight and brown without branches,” writes Hemingway in the mind of the young Nick Adams. He continues, “Around the grove of trees was a bare space. It was brown and soft underfoot as Nick walked on it. . . . The trees had grown tall and the branches moved high. . . . Sharp at the edge of this extension of the forest floor commenced the sweet fern” (In Our Time 137). These are direct sentences in observation of the vertical lines and hard edges which the protagonist and the author admire. Both the sentence structure and the semantics support the design values of the “clean tower,” the skyscraper. They also point up the irony of Hemingway’s relation to nature. He is much identified as a lover of nature, but his prose style insists that his deepest allegiance lies with the geometric forms of twentieth-century urban civilization.

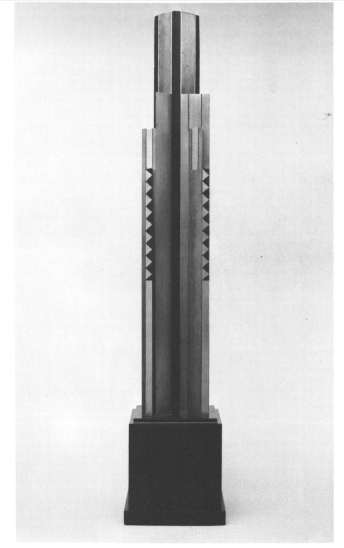

William Carlos Williams’s participation in the skyscraper ethos lies in part in his poetic line. He was a miniaturist of the skyscraper form, somewhat like the sculptor John Storrs, whose Forms in Space (1924) is small in dimension (28 1/2" × 5 1/2") but formally indebted to the modern skyscraper. In Williams’s poetry, the swift thrust of the skyscraper finds its formal counterpart in the emphatically vertical line, here in “Perpetuum Mobile: The City”:

There!

There!

There!

John Storrs, Forms in Space, 1924. Aluminum, brass, copper, and wood on a black marble base. 28 1/2 × 5 1/2 × 5 1/2 inches (Courtesy Collection of Whitney Museum of American Art, Gift of Charles Simon)

—a dream

of lights

hiding

the iron reason

and stone

a settled

cloud—

City (CEP 389)

The lines are obviously critical of urban realities, “iron reason” masked by an illusive “dream / of lights.” And of course we must read from top to bottom, visually a return voyage from the tower to its base. Williams’s lines, however, move with a skyscraper’s swiftness. They are as close as possible to a vertical drop. And they are punctuated by the indentations that appear on the page like the sculpted setbacks of the skyscraper form. In fact, on the page Williams’s metrics of what he called the “variable foot” move in the pattern of the classic skyscraper setbacks.

Each of these writers built differently, of course. Yet their work consistently elaborates the paradox presented by the skyscraper. It is a fixed form designed to feel like a kinetic one. Rooted in place, it soars, a representative form for the rapid-transit age.