THE ARAB TOWN (7th-16th Cents.)

During the thousand years and more that intervene between the Arab conquest of Egypt and its conquest by Napoleon, the events in the history of Alexandria are geographic rather than political. Neglected by man, the land and the waters altered their positions, and could Alexander the Great have returned he would have failed to recognise the coast. (i) The fundamental change was in the 12th cent., when the Canopic mouth of the Nile silted up. Consequently the fresh water lake of Mariout, being no longer fed by the Nile floods, also silted and ceased to be navigable. Alexandria was cut off from the entire river system of Egypt, and could not flourish until it was restored; she has always required the double nourishment of fresh water and salt. (ii) There was also a change in the outline of the city: the dyke Heptastadion, built by the Ptolemies to connect the mainland with the island of Pharos, fell into ruin and became a backbone along which a broad spit of land accreted; and so Pharos turned from an island into a peninsula — the present Ras-el-Tin.

The Arabs, though they let the city fall out of repair, admired it greatly. One of them writes as follows: —

The city was all white and bright by night as well as by day. By reason of the walls and pavements of white marble the people used to wear black garments; it was the glare of the marble that made the monks wear black. So too it was painful to go out by night ... a tailor could see to thread his needle without a lamp. No one entered without a covering over his eyes.

A second writer describes the green silk awnings that were spread over the Canopic Way. A third, even more enthusiastic exclaims: —

I have made the Pilgrimage to Mecca sixty times, but if Allah had suffered me to stay a month at Alexandria and pray on its shores, that month would be dearer to me.

The Arabs were anything but barbarians; their own great city of Cairo is a sufficient answer to that charge. But their civilisation was Oriental and of the land; it was out of touch with the Mediterranean civilisation that has evolved Alexandria. At first they made some effort to adapt it to their needs. The church of St. Theonas became part of the huge “Mosque of the 1,000 Columns;” the church of St. Athanasius also became a Mosque — the present Attarine Mosque occupies part of its site; and a third Mosque, that of the Prophet Daniel, rose on the Mausoleum of Alexander. But the Caesareum, the Mouseion, the Pharos, the Ptolemaic Palace, all became ruinous. So did the walls. And though the Arabs built new walls in 811, their course is so short that they vividly illustrate the decline of the town and of the population. (See map p. 98). They only enclosed a fragment of the ancient city.

In 828 the Venetians, according to their own account, stole from Alexandria the body of St. Mark, concealing it first in a tub of pickled pork in order to repel the attentions of the Moslem officials on the quay. The theft was a pardonable one, for the Arabs never seem to know that it had been made; it occasioned much satisfaction in Venice and no inconvenience in Alexandria. St. Mark procured, there was little to attract the European world; the ports of Egypt were now Rosetta (Bolbitiné Mouth of the Nile), and Damietta (Phatnitic Mouth); there was no reason to approach Alexandria now that her water system had collapsed. Towards the end of the Arab rule she did indeed regain some slight importance; the Mameluke Sultan of Cairo, Kait Bey, built on the ruins of the Pharos the fine fort that bears his name (1480). He built it as a defence against the growing naval power of the Turks. The Turks conquered Egypt in 1517, and a new but equally unimportant chapter in the history of Alexandria begins.

St. Theonas: p. 170.

Attarine Mosque: p. 143.

Mosque of the Prophet Daniel: p. 104.

Fragment of Arab Wall: p. 106, 155.

Fort Kait Bey: p. 133.

THE TURKISH TOWN (16th-18th Cents.)

Under the Turks the population continued to shrink, so that eventually the narrow enclosure of the Arab walls became too large. A new settlement sprang up on the neck of land that had formed between the two harbours. It still exists and is known as the “Turkish Town.” A second-rate affair; little more than a strip of houses intermixed with small mosques; a meagre copy of Rosetta, where the architecture of these centuries can best be studied. So unimportant a place can have no connected history. All that one can do is to quote the isolated comments of a few travelers. (i) The English sailor, John Foxe, (1577) has a lively tale to tell. He had been caught by the Turkish corsairs and imprisoned with his mates. With the connivance of a friendly Spaniard he organised a mutiny, recaptured his ship and in true British style worked it out of the Eastern Harbour under the fire of the guns on Kait Bey. (ii) John Sandys (1610) gives a quaint but impressive description of the decay: —

Such was this Queen of Cities and Metropolis of Africa: who now hath nothing left her but ruins; and those ill witnesses of his perished beauties: declaring rather that towns as well as men have the ages and destinies.... Sundry Mountains were raised of the ruins, by Christians not to be mounted; lest they should take too exact a survey of the city: in which are often found, (especially after a shower) rich stones and medals engraven with the figure of their Gods and men with such perfection of Art as these now cut seeme lame to those and unlively counterfeits.

(iii). Captain Norden, a Dane, (1757) was in an irritable mood, as the Turks would not let him sketch the fortifications. The English community was already in existence, and the Captain’s account of it makes interesting if painful reading: —

They keep themselves quiet and conduct themselves without making much noise. If any nice affair is to be undertaken they withdraw themselves from it and leave to the French the honour of removing all difficulties. When any benefits result from it they have their share and if affairs turn out ill they secure themselves in the best manner they can.

Extrait des Observations de plvsieurs singvlaritez etc.

par Pierre Belon du Mans

Paris 1554

(iv). Another irritable visitor landed here in 1779 — the lively but spiteful Mrs. Eliza Fay. Being a Christian, she was not allowed to disembark in the Western Harbour nor to ride any animal nobler than a donkey. She visited Cleopatra’s Needles and Pompey’s Pillar, then writes to her sister “I certainly deem myself very fortunate in quitting this place so soon.” She makes no mention of the English community, but was entertained by the Prussian Consul, and has left an unflattering account of his stout wife.

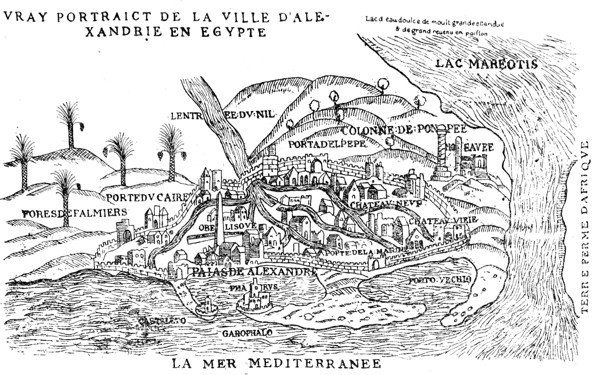

There are some old maps, compiled from the accounts of travellers, but bearing little reference to reality. That of Pierre Belon (1554) is reproduced on p. 83. Its main errors are the introduction of the Nile, and the outflow of Lake Mariout to the sea. It shows the two harbours, the Arab walls, Cleopatra’s Needles, Pompey’s Pillar and the Canopic or Rosetta Gate (Porte du Caire). The Turkish town has not yet been built. De Monconys’ map of 1665 — see frontispiece — is in some ways still more absurd; Cleopatra’s Needle has turned into a pyramid. The mound in the right centre is meant for Fort Cafarelli. The beginnings of the Turkish Town appear on Ras-el-Tin. In 1743 Richard Pocock published the first scientific map in his “Description of the East;” measurements and soundings are given. Captain Norden the Dane brought out a good pictorial plan of the “New,” i.e. Eastern harbour, showing the seamarks. And the exact extent of Alexandria’s decay is shown in the magnificent map published by the French expedition under Napoleon. There we see that the Arab enclosure is empty except for a few houses on Kom-el-Dik and by the Rosetta Gate, and that the population — only 4,000 — is huddled into the wall-less Turkish Town.

With Napoleon a new age begins.

Turkish Town: p. 124.

Rosetta: p. 185.

Cleopatra’s Needles: p. 161.

Pompey’s Pillar: p. 144.

Fort Cafarelli: p. 170.