NAPOLEON (1798-1801).

On July 1st 1798 the inhabitants of the obscure town saw that the deserted sea was covered with an immense fleet. Three hundred sailing ships came out from the west to anchor off Marabout Island, men disembarked all night and by the middle of next day 5,000 French soldiers under Napoleon had occupied the place. They were part of a larger force, and had come under the pretence of helping Turkey, against whom Egypt was then having one of her feeble and periodic revolts. The future Emperor was still a mere general of the French Republic, but already an influence on politics, and this expedition was his own plan. He was in love with the East just then. The romance of the Nile valley had touched his imagination, and he knew that it was the road to an even greater romance — India. At war with England, he saw himself gaining at England’s expense an Oriental realm and reviving the power of Alexander the Great. In him, as in Mark Antony, Alexandria nourished imperial dreams. The expedition failed but its memory remained with him: he had touched the East, the nursery of kings.

Leaving Alexandria at once, he marched on Cairo and won the battle of the Pyramids. Then an irreparable disaster befel him. He had left his admiral, Brueys, with instructions to dispose the fleet as safely as possible, since Nelson was known to be in pursuit. Under modern conditions Brueys would have sailed into the Western Harbour, but in 1798 the reefs that cross the entrance had not been blasted away, and though the transports got in the passages were rather dangerous for the big men-of-war. Brueys was nervous and thought he had better take them round to an anchorage, supposed impeccable, in the Bay of Aboukir. Nelson followed him, attacked him unexpectedly and destroyed his fleet. Details of this famous engagement, the so-called “Battle of the Nile,” are given in another place (p. 177); its result was to lose for Napoleon the command of the sea. The French expedition took Cairo and remained powerful on land, but could receive no reinforcements, no messages, and withered away like a plant that has been cut at the root. Turkey declared against it, and a Turkish force, supported by British ships, landed at Aboukir (July 1799). Here Napoleon was successful. He commanded in person and in a series of brilliant engagements drove the invaders into the sea: this is the “Land” battle of Aboukir (described in detail p. 179). But his dreams had been shattered by Nelson. He saw that his destiny, whatever it was, would not be accomplished in the East, and meanly deserting his army he slipped back to France.

We now come to the first British expedition, and to its successful and interesting campaign. In March 1801 Sir Ralph Abercrombie landed with 1,500 men at Aboukir. His aim was not to occupy Egypt, but to induce the French armies to evacuate it. He marched westward against Alexandria, keeping close to the sea. The country on his left was very different to what it is now, and to understand his operations two of the differences must be remembered. (i) The “Lake of Aboukir,” since drained, stretched from Aboukir Bay almost as far as Ramleh. As it connected with the sea, it was full of salt water. (ii) The present Lake Mariout was almost dry. It contained a little fresh water, but most of its enormous bed was under cultivation. It lay twelve feet below the waters of Lake Aboukir, and was protected from them by a dyke. Thus Abercrombie saw water where we see land, and vice versa. He advanced with success as far as Mandourah, because his left flank was protected by Lake Aboukir. But when he wanted to attack the French position at Ramleh he feared they would outflank him over the dry bed of Mariout. His losses had been heavy, his advance was held up; wounded in the thigh by a musket shot, he had to abandon the command, and was carried on to a boat where he died; a small monument at Sidi Gaber commemorates him to-day. His successor, Hutchinson, took drastic measures. At the advice of his engineers he cut the dyke that separated Lake Aboukir from Mariout. The salt water rushed in, to the delight of the British soldiers, and in a month thousands of acres had been drowned, Alexandria was isolated from the rest of Egypt, and the left flank of the expedition was protected all the way up to the walls of the town. Later in the year a second British force landed to the west of Alexandria, at Marabout, and, caught between two fires, the French were obliged to surrender. They were given easy terms, and allowed to leave Egypt with all the honours of war. The British followed them; we had accomplished our aim, and had no reason to remain in the country any longer; we left it to our allies the Turks. But the sleep of so many centuries had been broken. The eyes of Europe were again directed to the deserved shore. Though Napoleon had failed and the British had retired, a new age had begun for Alexandria. Life flowed back into her, just as the waters, when Hutchinson cut the dyke, flowed back into Lake Mariout.

Marabout: p. 171.

“Battle of the Nile”: p. 177.

Lake Mariout: p. 190.

Ramleh: p. 166.

Abercrombie Monument, Sidi Gaber: p. 165.

Tomb of Col. Brice, d. 1801 (Greek Patriarcate): p. 106.

MOHAMMED ALI (1805-1848).

When Napoleon drove the Turks into the sea at Aboukir, among the fugitives was Mohammed Ali, the founder of the present reigning house of Egypt. Little is known of his origin. He was an Albanian, but born at Cavala in Macedonia where he is said to have distinguished himself as a tax collector in his earlier youth. His education was primitive; he was ignorant of history and economics and only learnt the Arabic alphabet late in life. But he was a man of great ability and power and an acute judge of character. He reappears in Egypt in 1801, still obscure, and fights under Abercrombie. When the English withdrew he profited by the internal disturbances and became in 1805 Viceroy of the country under the Sultan of Turkey.

His power was consolidated by the disastrous British expedition of 1807 — General Frazer’s “reconnoitering” expedition, as it is officially termed. England was hostile to Turkey now, and Frazer was sent to see whether a diversion could be created in Egypt. He landed, like Napoleon before him, at Marabout, but with no more than the following regiments; — the 31st, the 35th, the 78th, and a foreign legion: 4,000 men in all. He occupied Alexandria and Rosetta, but before long Mohammed Ali had killed or captured half his force and he was obliged to ask for terms. They were readily granted. The “reconnoitering” expedition was allowed to reembark, and the only trace it has left of its presence in Alexandria is a tombstone of a soldier of the 78th, in the courtyard of the Greek Patriarchate.

For thirty years the power of Mohammed Ali grew, and with it the importance of Alexandria, his virtual capital. He freed the Holy Places of Arabia from a heretical sect, he interfered in Greece, he revolted against his suzerain the Sultan of Turkey, and invading Syria added it to his dominions. A kingdom, comparable in extent to the Ptolemaic, had come into existence with Alexandria as its centre, and it seemed that the dreams of Napoleon would be realised by this Albanian adventurer, and that the English would be cut off from India. England took alarm. And suddenly the empire of Mohammed Ali fell. Syria revolted (1840), supported by a British fleet, and soon the English admiral, Sir Charles Napier, was at Alexandria, and compelled the Viceroy to confine himself to Egypt. According to tradition the interview took place in the new Ras-el-Tin Palace, and Napier exclaims “If Your Highness will not listen to my unofficial appeal to you against the folly of further resistance, it only remains for me to bombard you, and by God I will bombard you and plant my bombs in the middle of this room where you are sitting.” Anyhow Mohammed Ali gave in. He had failed as a European power, but he had secured for his family a comfortable principality in Egypt, where he was king in all but name.

His internal policy was rather disreputable. He admired European civilization because it made people aggressive and gave them guns, but he had no sense of its finer aspects, and his “reforms” were mainly veneer to impress travellers. He exploited the fellahin by buying grain from them at his own price: the whole of Egypt became his private farm. Hence the importance of the foreign communities at Alexandria at this date: he needed their aid to dispose of the produce in European markets. He won over the British and other consuls to be his agents by giving them licences to export Egyptian antiquities, which were then coming into fashion; our own Consul Henry Salt — his tomb is here — was a particular offender in this. He also gave away “Cleopatra’s Needles” to the British and American Governments respectively; the obelisks that still remained on their original sites outside the vanished Caesareum, and would have lent such dignity to our modern sea front. Still, with all his faults, he did create the modern city, such as she is. He waved his wand, and what we see arose from the aged soil. Let us examine it for a moment.

Statue of Mohammed Ali: p. 102.

Mausoleum of his Family: p. 105.

Tomb of Soldier of the 78th: p. 106.

Ras-el-Tin Palace: p. 129.

Tomb of Henry Salt: p. 144.

Cleopatra’s Needles: pp. 136, 162.

THE MODERN CITY.

During the years 1798-1807 as many as four expeditions had landed at or near Alexandria — one French, one Turkish, and two English. Egypt had again been drawn into the European system. A maritime capital was necessary, and the genius of Mohammed Ali realised that it could be found not in the mediaeval ports of Damietta and Rosetta, but in a restored Alexandria. The city that we know to-day has followed the lines that he laid down, and it is interesting to compare his dispositions with those of Alexander the Great, over two thousand years before.

The main problem was the waters. The English, by cutting the dykes in 1801, had refilled Lake Mariout so that it had suddenly regained its ancient area. But it was too shallow for navigation and they had filled it with salt water instead of the former fresh: it gave no access to the system of the Nile. That system had to be tapped. Alexander could find the Nile at Aboukir (Canopic Mouth): now it was as far off as Rosetta (ancient Bolbitic Mouth). Consequently Mohammed Ali had to construct a canal 45 miles long. This canal, called the Mahmoudieh after Mahmoud, the reigning Sultan of Turkey, was completed in 1820. It was badly made and the sides were always falling in, but it led to the immediate rise of Alexandria and to the decay of Rosetta. Alexandria now had water communications with Cairo, to which was added communication by rail. The Harbour followed. Mohammed Ali developed the Western which had been the less important in classical times. The present docks and arsenals were built for him (1828-1833) by the French engineer De Cerisy. A fleet was added. To the same scheme belongs the impressive Ras-el-Tin Palace, which standing on a rise above the harbour dominated it as the Ptolemaic Palace had once dominated the Eastern; the favourite residence of the Viceroy, it indicated that his new kingdom was no mere oriental monarchy, but a modern power with its face to the sea.

Meanwhile the town started its development, but not on very regal lines. Houses began to run up and streets to sprawl over the deserted area inside the Arab Walls. It did not occur either to Mohammed Ali or to his friends the Foreign Communities that a city ought to be planned. Their one achievement was a Square and certainly quite a fine one — the Place des Consuls, now Place Mohammed Ali. The English were granted land to the north of the Square, on part of which they built their church, the French and the Greeks land to the south; areas were also acquired by other communities, e.g. by the Armenians. But there was no attempt to coordinate the various enterprises, or to utilise the existing features of the site. These features were: the sea, the lake, Pompey’s Pillar, the forts of Kom-el-Dik and Cafarelli, and the Arab Walls. The sea was ignored except for commercial purposes; the main thoroughfares still keep away from its shores, and even the fine New Quays are attracting no buildings to their curve. The lake was ignored even more completely — the lake whose delicate pale expanse might so have beautified the southern quarters; many people do not know that a lake exists. Pompey’s Pillar, instead of being the centre of converging roads, has been left where it will least be seen; only down the Rue Bab Sidra does one get a distant view of it. Similarly with the two forts; huddled behind houses. The Arab walls have been finally destroyed — remnants surviving in the eastern reach where they have been utilised (and well utilised) in the Public Gardens.

As Alexandria grew in size and wealth she required suburbs. The earliest development was along the line of the Mahmoudieh Canal, where the Villa Antoniadis and a few other fine houses have been built. But with the improvement of communications the rich merchants were able to live further afield. Two alternatives were open to them — Mex and Ramleh — and rather regrettably they selected the latter. Mex, with its fine natural features, might have developed into a very beautiful place: as it is a belt of slums have parted it from the town, and an execrable tram service has removed it even further. The town has spread to the east instead, to Ramleh, served at first by a railway and now by good electric trams.

Such are the main features of Alexandria as it has evolved under Mohammed Ali and his successors. It does not compare favourably with the city of Alexander the Great. On the other hand it is no worse than most nineteenth century cities. And it has one immense advantage over them — a perfect climate.

Mahmoudieh Canal: p. 151.

Modern Harbour: p. 129.

Ras-el-Tin Palace: p. 129.

Square: p. 102.

English Church: p. 102.

Fort Kom-el-Dik: p. 106.

Fort Cafarelli: p. 170.

Pompey’s Pillar: p. 144.

Public Gardens: p. 154.

Villa Antoniadis: p. 157.

Mex: p. 171.

Ramleh: p. 166.

THE BOMBARDMENT OF ALEXANDRIA (1882).

Thus the city develops quietly under Mohammed Ali and his successors — one of whom, Said Pasha, is buried here. Attention was rather diverted from her by the cutting of the Suez Canal, and it is not until 1882 that anything of note occurs. She is in this year connected with the rebellion of Arabi, the founder of the Egyptian Nationalist Party. Arabi, then Minister of War, was endeavouring to dominate the Khedive Tewfik, and to secure Egypt for the Egyptians. Alexandria, which had held a foreign element ever since its foundation, was therefore his natural foe, and it was here that he opened the campaign against Europe that ended in his failure at Tel-el-Kebir. The details — like Arabi’s motives — are complicated. But four stages may be observed.

(i). Riot of June 11th.

This began at about 10 p.m. in the Rue des Soeurs; it is said that two donkey boys, one Arab and one Maltese, had a fight in a café, and that others joined in. The rioters moved down towards the Square, and at some cross roads near the Laban Caracol the British Consul was nearly killed. They were joined in the Square by two other mobs, one from the Attarine Quarter and one from Ras-el-Tin. British and other warships were in the harbour, but took no action, and the Egyptian troops in the city refused to intervene without orders from Arabi, who was in Cairo. At last a telegram was sent to him. He responded and the disorder ceased. There is no reason to suppose that he planned the riot. But naturally enough he used it to increase his prestige. He had shown the foreign communities, and particularly the British, that he alone could give them protection. In the evening he came down in triumph from Cairo. About 150 Europeans are thought to have been killed that day, but we have no reliable statistics.

(ii). Bombardment of July 11th.

British men-of-war under Admiral Seymour had been in the harbour during the riot, but it was a month before they took action. In the first place the British residents had to be removed, in the second the fleet required reinforcing, in the third orders were awaited from home. As soon as Seymour was ready he picked a quarrel with Arabi and declared he should bombard the city if any more guns were mounted in the forts. Since Arabi would not agree he opened fire at 7.0 a.m. July 11th. There were eight iron-clads — six of them the most powerful in our navy. They were thus distributed: — Monarch, Invincible and Penelope close inshore off Mex; Alexandra Sultan and Superb off Ras-el-Tin; while the two others the Temeraire and Inflexible were in a central position outside the harbour reef, half-way between Ras-el-Tin and Marabout; and off Marabout were some gun boats, under Lord Charles Beresford. The bombardment succeeded, though Arabi’s gunners in the forts fought bravely. In the evening the Superb blew up the powder magazine in Fort Adda. Fort Kait Bey was also shattered and the minaret of its 15th cent. Mosque was seen “melting away like ice in the sun.” The town, on the other hand, was scarcely damaged, as our gunners were careful in their aim. Arabi and his force evacuated it in the evening, marching out by the Rue Rosette to take up a position some miles further east, on the banks of the Mahmoudieh canal.

(iii). Riot of July 12th.

Unfortunately Admiral Seymour, after his success, never landed a force to keep order, and the result was a riot far more disastrous than that of June. With the withdrawal of Arabi’s troops the native population lost self control. The Khedive had now broken with Arabi, but during the bombardment he had moved from Ras-el-Tin Palace to Ramleh and his authority was negligible. Pillaging went on all day on the 12th, and by the evening the city had been set on fire. The damage was material rather than artistic, the one valuable object in the Square, the statue of Mohammed Ali, fortunately escaping. Rues Chérif and Tewfik Pacha — indeed all the roads leading out of the Square — were destroyed, and nearly every street in the European quarter was impassable through fallen and falling houses. Empty jewel cases and broken clocks lay on the pavements. Every shop was looted, and by the time Admiral Seymour did land it was impossible for his middies to buy any jam; one of them has recorded this misfortune, adding that in other ways Alexandria, then in flames, was “well enough.” Meanwhile the Khedive had returned to his Palace, and order was slowly restored. It is not known how many lives were lost in this avoidable disaster.

(iv). Military Operations.

A large British force was despatched under Lord Wolseley to the Suez Canal — the force that finally defeated Arabi at Tel-el-Kebir. But, until it reached Egypt, Alexandria remained in danger, for Arabi might attack from his camp at Kafr-el-Dawar. So the city had to be defended on the east. In the middle of July General Alison arrived with a few troops, including artillery, and occupied the barracks at Mustapha Pacha, the hill of Abou el Nawatir, and the water works down by the canal. He could thus watch Arabi’s movements. And he had a second strongly fortified position at the gates of the Antoniadis Gardens, in case he was attacked from the south. Here he was able to hold on and to harry the enemy’s outposts until pressure was relieved. His losses were slight; the regiments involved are commemorated by tablets in the English church. Next month Wolseley arrived, and having inspected the position re-embarked his troops and pretended that he was going to land at Aboukir. Arabi was deceived and prepared resistance there. Wolseley steamed past him, and landed at Port Said instead. Arabi then had to break up his camp, and the danger for Alexandria was over.

Rue des Sœurs: p. 170.

Fort Adda: p. 132.

Fort Kait Bey: p. 133.

Mustapha Barracks: p. 96.

Gun on Abou el Nawatir: p. 165.

Antoniadis Gardens: p. 157.

Tablets in English Church: p. 103.

Howitzer of Arabi; at Egyptian Government Hospital: p. 163.

CONCLUSION.

Since the bombardment of 1882, the city has known other troubles, but they will not be here described. Nor will any peroration be attempted, for the reason that Alexandria is still alive and alters even while one tries to sum her up. Politically she is now more closely connected with the rest of Egypt than ever in the past, but the old foreign elements remain, and it is to the oldest of them, the Greek, that she owes such modern culture as is to be found in her. Her future like that of other great commercial cities is dubious. Except in the cases of the Public Gardens and the Museum, the Municipality has scarcely risen to its historic responsibilities. The Library is starved for want of funds, the Art Gallery cannot be alluded to, and links with the past have been wantonly broken — for example the name of the Rue Rosette has been altered and the exquisite Covered Bazaar near the Rue de France destroyed. Material prosperity based on cotton, onions, and eggs, seems assured, but little progress can be discerned in other directions, and neither the Pharos of Sostratus nor the Idylls of Theocritus nor the Enneads of Plotinus are likely to be rivalled in the future. Only the climate only the north wind and the sea remain as pure as when Menelaus the first visitor landed upon Ras-el-Tin, three thousand years ago; and at night the constellation of Berenice’s Hair still shines as brightly as when it caught the attention of Conon the astronomer.

THE GOD ABANDONS ANTONY.

When at the hour of midnight

an invisible choir is suddenly heard passing

with exquisite music, with voices —

Do not lament your fortune that at last subsides,

your life’s work that has failed, your schemes that have proved illusions.

But like a man prepared, like a brave man,

bid farewell to her, to Alexandria who is departing.

Above all, do not delude yourself, do not say that it is a dream,

that your ear was mistaken.

Do not condescend to such empty hopes.

Like a man for long prepared, like a brave man,

like to the man who was worthy of such a city,

go to the window firmly,

and listen with emotion,

but not with the prayers and complaints of the coward

(Ah! supreme rapture!)

listen to the notes, to the exquisite instruments of the mystic choir,

and bid farewell to her, to Alexandria whom you are losing.

C. P. Cavafy.

[The local reference of this exquisite poem is to the omen that heralded the defeat of Mark Antony (p. 26). The poet is eminent among the contemporary writers of Greece; he and his translator, Mr. George Valassopoulo, are both residents of Alexandria.]

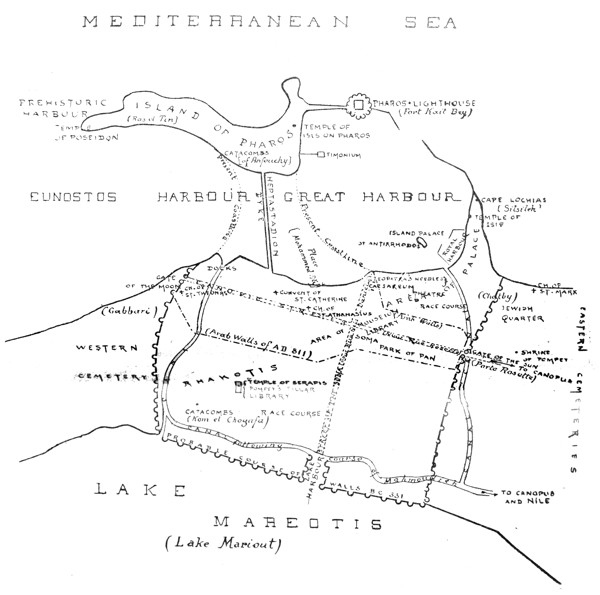

Alexandria: Historical Map

Ancient Sites in Capitals

Modern Sites bracketed (...)