Route: — By train from the Main (Cairo) sta., or from Sidi Gaber, where all trains stop, and which is also a sta. for the Ramleh tram (Section VI).

Chief Points of Interest: — Montazah; Canopus; Aboukir Bay; Rosetta.

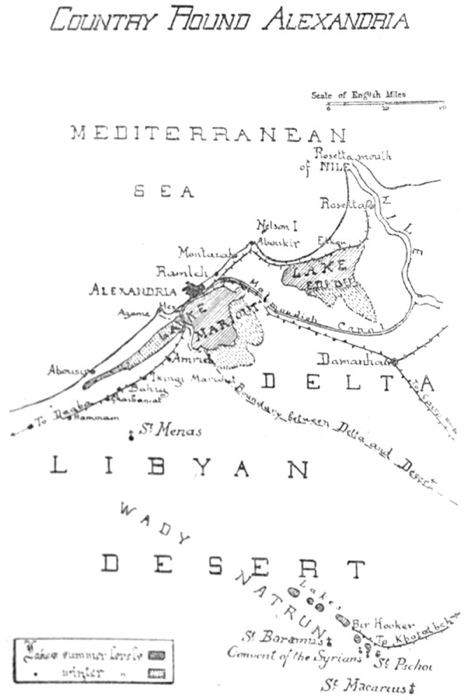

Country Round Alexandria

At Sidi Gaber sta. is a view of Lake Hadra on the right. — Five stations on: — Victoria, close to the College and tram terminus. — The train passes over sand and through a palm oasis, which is carpeted with flowers in spring.

Mandarah Sta. — One of the houses in the village is painted outside in commemoration of the inmates pilgrimage to Mecca — pictures of things that he saw or would like to have seen, such as a railway train, a tiger, a siren, and a very large melon.

Montazah Sta. — Close to the station is the Summer Resort of the ex-Khedive Abbas II, now (1922) being restored and refurnished by King Fouad. Permission to enter should be obtained if possible, for the scenery is unique in Egypt and of the greatest beauty. The road leads by roses, oleanders and pepper trees. From it a road turns, right, up the hill to the Selamlik (men’s quarters), built by the Khedive in a style that was likely to please his Austrian mistress; on the terrace in front is a sun dial and some guns. From the terrace, View of the circular bay with its fantastic promontories and breakwaters; the coast to the right is visible as far as Aboukir, whose minaret peeps over a distant headland; to the left are the Montazah woods; beneath, down precipitous steps, a curved parade. Beautiful walks in every direction, and perfect bathing. On the promontory to the right is a kiosk, and at its point are some remains of buildings or baths — fragments of the ancient Taposiris Parva that once stood here; some of them form natural fishponds. The woods are Pines Maritimes, imported by the Khedive from Europe, and in the western section, beyond the Pigeon House, the trees have grown high. Various buildings are in the estate; in one corner are the foundations of an enormous mosque. During the recent war (1914-1919) Montazah became a Red Cross Hospital; thousands of convalescent soldiers passed through it and will never forget the beauty and the comfort that they found there.

Mamourah Sta.: The low ground to the right is on the site of the Aboukir Lake (p. 87), drained in the 19th cent. Here the Aboukir and Rosetta railways part.

ABOUKIR.

Route: — Aboukir Station is the terminus. Walk or take donkey. Turn sharply to the left to Canopus, 1 mile, then follow coast all the way round by Fort Kait Bey to Fort Ramleh; return to Aboukir Village.

Aboukir and District

Aboukir, though intimately connected with Alexandria, has a history of its own. Three main periods.

(i). Ancient (see also p. 7).

Geologically, this is the end of the long limestone spur that projects from the Lybian desert (p. 5). The Nile had to round it to reach the sea, and it is to the Nile that its early fame is due. The river poured out just to the east, through the “Canopic” Mouth, which has now dried up, and there were settlements here centuries before Alexandria was founded. On the left bank of the Nile (south of the present Fort Ramleh) Herodotus (B.C. 450) saw a temple to Heracles, and was told that Paris and Helen had sought shelter here on their flight to Troy — shelter that was refused by the local authorities, who disapproved of their irregular union. There was a second settlement at Menouthis (Fort Ramleh itself), and a third and most famous at Canopus (present Fort Tewfikieh), from which the whole district took its name.

Canopus, according to Greek legend, was a pilot of Menelaus who was bitten here by a serpent as they returned from Troy, and, dying, became the tutelary God. The legend, like that of Paris and Helen, shows how interested were the Greeks in the district, but has no further importance. There is also a legend that Canopus was an Egyptian God whose body was an earthenware jar: this too may be discredited. With the foundation of Alexandria (B.C. 331) the district lost much of its trade, but became a great fashionable and religious resort. There was a canal from Alexandria, probably connecting with the Nile just where it entered the sea, and the Alexandrians glided along it in barges, singing and crowned with flowers. In connection with his new cult of Serapis (p. 18) Ptolemy Soter built a temple here (see below) whose fame spread over the world and whose rites made the Romans blush with shame or pale with envy; here originated the idea, still so widely held in the west, that Egypt is a land of licentiousness and mystery. The district decayed as soon as Christianity was established; it had not, like Alexandria, a solid basis for its existence in trade. But Paganism lingered here, and as late as the end of the 5th century twenty camel-loads of idols were found secreted in a house and were carried away to make a bonfire at Alexandria. Demons gave trouble even in later times.

(ii). Christian.

The Patriarch Cyril (p. 51) having destroyed the cults of Serapis and Isis in the district (A.D. 389) sent out the relics of St. Cyr to take their place. The relics were so intermingled with those of another martyr, St. John, that St. John had to be brought too, and a church to them both arose just to the south of the present Fort Kait Bey. The two Saints remained quiet for 200 years, but then began to disentangle themselves and work miracles, and recovered for the district some of its ancient popularity; indeed many of their cures are exactly parallel to those effected in the temple of Serapis. With the Arab invasion their church vanishes, but St. Cyr has given his name to modern Aboukir (“Father Cyr.”) In the 9th century the Canopic branch of the Nile dried up. The Turks built some forts here for coastal defence, but history does not recommence until the arrival of Nelson.

(iii). Modern.

In Napoleonic times Aboukir saw two great battles.

(a). “Battle of the Nile.”

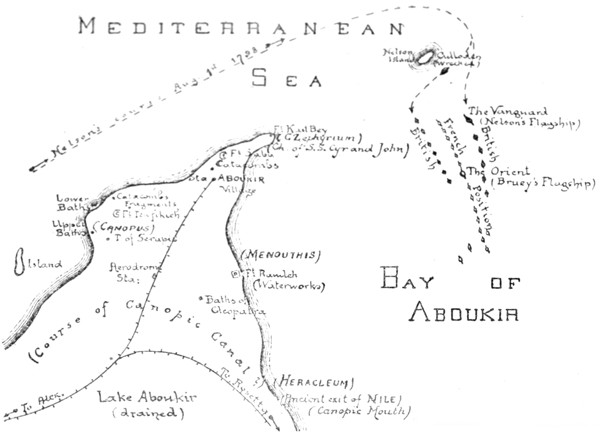

For the event that led to this engagement see p. 86. Brueys, Napoleon’s admiral, brought his fleet into the bay for safety, and anchored them in a long line, about two miles from the coast. He had 13 Men-of-War, 4 Frigates, 1182 canons, and 8000 men. To the north was “Nelson’s Island,” as it is now called, which he had fortified and upon which his line was supposed to rest. His flagship, the Orient, was midway in the line. He took up this position on July 7th, 1798.

On August 1st Nelson arrived in pursuit, with 14 Men-of-War, 1012 canons and 8068 men. The wind was N.W., a usual direction in summer. Half his fleet, including his flagship the Vanguard, attacked Brueys from the expected quarter, the east. The other half, led by the Goliath, executed the brilliant manœuvre that brought us victory. It gave Brueys a double surprise: in the first place it passed between the head of his line and “Nelson Island” where he thought there was no room; in the second place it took up a position to his west, between him and the shore, where he thought the water was too shallow. Thus he was caught between two fires — attacked by the whole British Fleet with the exception of the Culloden, which, sailing too near Nelson Island, stranded.

The engagement began at 6.00 p.m. At 7.00 Brueys was killed, at 9.30 the Orient caught fire and blew up shortly afterwards; the explosion was tremendous and terminated the first act of the battle; an interval of appalled silence ensued. Casabianca was sailing the Orient, and it was on her “burning deck” that the boy of Mrs. Hemans’ poem stood. The fighting recommenced, continuing through the night, and ending at midday on the 2nd with the complete victory of Nelson. The French fleet had been annihilated; only two Men-of-War and two Frigates escaped, and Napoleon had lost for ever his command of the Mediterranean. Nelson accordingly signalled the following message: —

Almighty God having blessed His Majesty’s arms with victory, the Admiral intends returning public thanksgiving for the same at two o’clock this day, and he recommends every ship doing the same as soon as convenient.

The French expected an attack on Alexandria, but Nelson had suffered too much himself to attempt this; having rested for a little, he dispersed his fleet, leaving only a few ships behind to watch the coast. In his despatches home he stated that the engagement had taken place not far from the (Rosetta) mouth of the Nile; hence the official “Battle of the Nile” instead of the more accurate “Naval Battle of Aboukir.”

(b). Land Battle of Aboukir.

Less important than its predecessor, but the strategy is interesting, and Napoleon himself was present. For the events that led up to it see p. 87; Turkey, at the instigation of England, had declared war on France, and in July 1799 the Turks occupied Aboukir Bay and landed 15,000 men. Their left rested on the present Fort Ramleh, their right on the present Fort Tewfikieh, their camp was in the narrow extremity of the peninsula, between the redoubt and the Fort at the very tip. They were supported on three sides by their fleet, which was stationed in the Mediterranean, in the Bay of Aboukir, and in the (vanished) Lake of Aboukir. From this stronghold they proposed to overrun Egypt.

On receiving the news, Napoleon hurried down from Cairo and arrived (July 25th) with only 10,000 men, mostly cavalry. Murat and Kléber accompanied him. He began by clearing the Turkish gun boats out of Lake Aboukir; then his force attacked Forts Ramleh and Tewfikieh, while his cavalry under Murat, advancing over the level ground between them, drove the flying defenders of each into the Mediterranean and the Bay respectively. 5,400 Turks were drowned. The tip of the peninsula remained and resisted vigorously, but Napoleon managed to mount some of his guns on the hard spit of sand that still extends along the shore of the Bay, and thus to cannonade the Turkish Camp, which was finally taken by storm.

Ruins of Canopus.

The ruins (see above) lie round Fort Tewfikieh which is seen to the left as the train runs into the station. They were once of interest, but have been almost entirely destroyed by the military authorities, who use the limestone blocks for road making, and allow treasure hunting to go on. The remains are not easy to find, as the area is pitted with excavations. Consult map.

(a) About 50 yds. from the gateway of the fort, in a hollow to the left of the road, are two huge Fragments of a granite temple. Here were found the busts of Rameses II in the Museum (Room 7) and the colossi of the same King and his daughter (Museum, Court). Date of statues: — B.C. 1300.

(b) Further to the left, round the Fort, is the site of the Temple of Serapis, the most famous building on the peninsula, and celebrated throughout the antique world. It was dedicated by Ptolemy III Euergetes (p. 15) and his wife Berenice. A few years later (B.C. 238) their baby daughter died, and the priests met here in conclave to make her a goddess, and incidentally to endorse some reforms in the Calendar that the King, who had a scientific mind, was pressing. The pronouncement has been preserved in the “Decree of Canopus,” now one of the chief documents for Ptolemaic history. As for miracles, the temple even outstripped the original Temple of Serapis at Alexandria: invalids who slept here even by proxy discovered next day that they were well. It was also the abode of magic and licentiousness according to its enemies, and of philosophy according to its friends. Christianity attacked it. Just before its destruction (A.D. 289) Antoninus, an able pagan reactionary, settled here, and tried to revive the cult. “Often he told his disciples that after his time there would be no temple, and that the great and venerable sanctuary would remain only as an unmeaning mass of ruins, forgotten by all.” (Eunapius, life of Edesius). Antoninus was right.

In ancient time the Temple probably stood on the highest ground, but with the general rising of level the site is now in a deep depression and must be hunted for patiently. An oblong space has been cleared and some columns and capitals from the excavations have been ranged round it, but it is impossible to reconstruct the original plan, and much has yet to be unearthed. Indeed it is not quite certain that this is the right temple; an inscription has been discovered dedicating it not to Serapis but to Osiris — with whom however Serapis was often identified. The columns are of granite or of stucco-coated limestone. Beneath the broken tin shelter was once a pretty mosaic. The finest object is a stupendous fluted column of red granite that lies in a pit close by; no use for it has yet occurred to the military authorities. To the south and east of the Temple were the houses of the priests, showing fine cemented passages; these have been destroyed.

The canal by which revellers and worshippers approached this shrine ran to the south, through the low land by the railway; its course is uncertain; its exit was either into the (vanished) Nile, or into Aboukir Bay.

(c) The Upper Baths. These lie about 100 yds. nearer the sea, on the slope just above the corner of the great bay that stretches to Montazah (p. 175). When excavated a few years ago they were almost perfect. The swimming bath — lined with the hard pink cement that indicates Ptolemaic or Roman work — had at the top a double step for the bathers. All round its sides were inserted large earthenware pots, their mouths level with the surface. Of this unique building a small fragment now survives. The brick central cistern and the hot baths can also still be traced.

(d). The Lower Baths and Broken Colossus. — Continuing to round Fort Tewfikieh we reach the coast and follow it N.E. Awash with the sea are the foundations of some large baths, showing the entrance channels which were probably closed with sluices, also some grooves of unknown use. On the shore above are the hot baths of the same establishment, retaining traces of pink cement. In the surf to the left lie blocks of granite: closely inspected, they resolve into fragments of a Colossus (Rameses II?) and a sphinx.

(e). Catacombs. — Fifty yards on, at a point about half-way between the coast and the fort are a couple of catacombs, lying each of them in a hollow. One has a subterranean room, the other a sarcophagus slide. Traces of tombs and tunnels all over the area and along the low cliff by the shore.

This completes our survey of Canopus, once so enchanting a spot. Of its ancient delights only the air and the sea remain.

Continue to follow the coast. Perfect bathing. To the right, half-way between the coast and the railway sta. in some rising ground, are catacombs that have been filled in. Then comes the end of the promontory, which is fine. There are two forts: — Fort Saba, closing the neck, where the French resisted when the Turks landed in 1799 (see above); and Fort Kait Bey, on the extremity, founded in the 15th cent. by the Sultan of that name as part of his defence scheme against the Turks (cf. Fort Kait Bey at Alexandria, p. 81). The views are good, with the Mediterranean on one side and the tranquil semi-circle of Aboukir Bay on the other, and from here or from Fort Ramleh the scene of the “Battle of the Nile” can be surveyed, and Nelson’s great manoeuvre appreciated; “Nelson’s Island” from which the French line depended and where the Culloden was wrecked lies straight ahead. (see above.) The promontory was anciently called Zephyrium, because it caught the cool zephyr winds; here stood a little temple to Aphrodite and when the great queen Arsinoe, died in B.C. 270, one of the court admirals had the happy idea of associating her with the elder goddess so that mariners might render thanks to both. The shrine then became fashionable and Queen Berenice hung up her hair here in 244 as a thank-offering for her husband’s safe return; in the following year the hair was snatched up to heaven, where it may still be observed on any fine night as the constellation of Coma Berenice. The temple was less fortunate, and all that remains of it is the base of a column, down among the rocks. — In Christian times the Church of St. Cyr and St. John (see above) stood here, on the side of Aboukir Bay.

Aboukir Bay. — The shore is airless and there are palm trees, the waters shallow. From a boat one can look down on the mud in which the Orient, Brueys’ flagship, has disappeared with all her treasure; attempts have been made to locate her, but in vain. Good sailing. Turtle fishing. On the projecting spit to which Napoleon dragged his guns (see above) is the landing enclosure for the fishing boats; many of the fishermen are Sicilians; they have lived at Aboukir for generations and form a community by themselves. Here (site uncertain) once stood Menouthis.

Fort Ramleh. — Topped by the waterworks. Magnificent view. The flat ground to the south marks the Canopic Mouth of the Nile, through which Herodotus entered Egypt; here Heracleum stood (see above).

About quarter mile S.W. of Fort Ramleh, and close to a small modern pumping tower, are the so-called Baths of Cleopatra. She had nothing to do with them, but they are worth seeing. The western outer wall, of limestone blocks, is well preserved. Steps lead up through it. Within are pavements of pebble mosaic, fragments of stucco, a stone with a drain groove, &c. In a chamber to the left, is an oblong bath nearly six feet deep; steps lead down to it and in the centre of its pebbled floor is a little depression; in the edge of the brim and on the wall opposite are niches, as if to support beams, and provision for the entrance and exit of the water can also be seen. Further on, past a small stucco cistern, is an entrance to a small room which contains an oblong bath to lie down in, quite modern and suburban in appearance; close to it, under a niche, is a footbath — the bather sat on a seat which has disappeared but whose supports can be seen. — These baths are all in the western part of the enclosure; the rest contains other and larger chambers but is in worse preservation. It is much to be wished that these baths, which have been recently excavated, could be protected properly; otherwise they will share the fate of the other antiquities within the military zone.

Aboukir Village, to which we return through palm trees, contains nothing of note.

On leaving Mamourah Junction (p. 176) the railway to Rosetta bears to the right, and crosses the salt marshy ground over which the Canopic branch of the Nile once flowed to the sea. Rural Egypt can be seen at last. Beyond El Tarh station the train crosses a bit of Lake Edku; view of the village to the left.

Edku (no hotel or café) stands on a high mound between the lake and the Mediterranean. The houses in its steep streets are of red brick strengthened with courses of palm and other woods; they anticipate the more complicated architecture of Rosetta; there are some carved doors, Italianate in style. Mosques, unimportant. On the top of the ridge are some eight sailed windmills; they grind corn. Fine date palms grow on the sand dunes towards the sea, for there is fresh water just beneath the surface. There is an interesting local weaving industry, chiefly of silk, imported in its rough state from China. The work rooms are generally on the upper floors of the houses, and reached by an outside staircase. Quiet pleasant places; on the walls of some are Cufic inscriptions, inlaid in brick. The weavers sit to their looms in small oval pits; they have the hands of craftsmen and produce on their simple wooden machinery fabrics that are both durable and beautiful.

Fish are caught in Lake Edku. Some of the fishermen wade far into shallow waters; there is also a fleet of boats which moor to the long wooden jetty by the station. Occasional flamingoes.

The railway continues between lake and sea, finally bending northward and curving round great groves of palm trees, behind which lie the town of Rosetta and the river Nile.

ROSETTA.

Rosetta and Alexandria are rivals; when one rises the other declines. Rosetta, situated on the Nile, would have dominated but for an overwhelming drawback: she has, and can have, no sea-harbour, because the coast in this part of Egypt is mere delta; the limestone ridges that created the two harbours of Alexandria do not continue eastward of Aboukir. Alexandria required organising by human science, but once organised she was irresistible. It is only in an unscientific age that Rosetta has been important. Let us briefly examine the birth and death, rebirth and decay, of civilisation here.

(i). In Pharaonic times the town and river-port of Bolbitiné were built hereabouts — probably a little up stream, beyond the present mosque of Abou Mandour. Nothing is known of the history of Bolbitiné. When Alexandria was founded (B.C. 331) traffic deserted the “Bolbitiné” mouth of the Nile for the “Canopic” and for the Alexandrian harbours, and the town decayed consequently. Its chief memorial is the so-called “Rosetta Stone,” a basalt inscription now in the British Museum. The inscription enumerates the merits of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes (B.C. 196; see genealogical tree p. 12). It is a dull document, a copy of the original decree which was set up at Memphis and reproduced broadcast over the country. But it is important because it is written in three scripts — Hieroglyphic, Demotic and Greek — and thus led to the deciphering of the ancient Egyptian language. The antique columns &c. that may be seen in Rosetta to-day also probably came from Bolbitiné. But it was never important, and the sands have now covered it.

(ii). Rosetta itself was founded in A.D. 870 by El Motaouakel, one of the Abbaside Caliphs of Egypt. The date is most significant. By 870 the Canopic mouth of the Nile had dried up, and isolated Alexandria from the Egyptian water system. Shipping passed back to the Bolbitiné mouth, and frequented it again for nearly a thousand years. “El Raschid” as the Arabs named the new settlement, became the western port of Egypt, Damietta being the eastern. It was important in the Crusades; St. Louis of France (1049) knew it as “Rexi.” In the 17th and 18th centuries it was practically rebuilt in its present form; the mosques, dwelling houses, cisterns, the great warehouses for grain that line the river bank, all date from this period, it evolved an architectural style, suitable to the locality. The chief material is brick, made from the Nile mud, and coloured red or black, there was no limestone to hand, such as supplied Alexandria: with the bricks are introduced courses of palm wood, antique columns &c. and a certain amount of mashrabiyeh work and faience. The style is picturesque rather than noble and may be compared with the brick style of the North German Hansa towns. Examples of it are to be found throughout the Delta and even in Alexandria herself (p. 125), but Rosetta is its head quarters. In architecture, as in other matters, the town kept in touch with Cairo; an Oriental town, scarcely westernised even to-day. So long as Alexandria lay dormant, it flourished; at the beginning of the 19th century its population was 35,000, that of Alexandria 5,000.

In 1798 Napoleon’s troops took Rosetta, in 1801 the British and Turks retook it, in 1807 the reconnoitring expedition of General Frazer (p. 89) was here repulsed. These events, unimportant in themselves, were the prelude to an irreparable disaster: the revival of Alexandria, on scientific lines, by Mohammed Ali. As soon as he developed the harbours there and restored the connection with the Nile water systems by cutting the Mahmoudieh Canal, (p. 91), Rosetta began to decay exactly as Bolbitiné had decayed two thousand years before. The population now is 14,000 as against Alexandria’s 400,000, and it has become wizen and puny through inbreeding. The warehouses and mosques are falling down, the costly private dwellings of the merchants have been gutted, and the sand, advancing from the south and from the west, invades a little farther every year through the palm groves and into the streets. One can wander aimlessly for hours (it is best thus to wander) and can see nothing that is modern, nor anything more exciting than the arrival of the fishing fleet with sardines. It is the East at last, but the East outwitted by science, and in the last stages of exhaustion.

The main street of Rosetta starts from the Railway Station and runs due south, parallel to the river, so it is easy to find one’s way. In it is the only hotel, kept by a Greek; those who are not fastidious can sleep here: the rest must manage to see the sights between trains. The hotel has a pleasant garden, overlooked by the minaret of a mosque.

In the main street, to the right; — Mosque of Ali-el-Mehalli, built 1721, but containing the tomb of the Saint, who died in the 16th century. A large but uninteresting building, with an entrance porch in the “Delta” style — bricks arranged in patterns, pendentives, &c.

Further down, to the left, by the covered bazaars: Entrance with old doors to a large ruined building, probably once an “okel” or courtyard for travellers and their animals; one can walk through it and come out the other side through a fine portal, in the direction of the river. All this part of the town is most picturesque. The houses are four or five stories high, and have antique columns fantastically disposed among their brickwork. The best and oldest example of this domestic architecture is the House of Ali-el-Fatairi, in the Haret el-Ghazl, with inscriptions above its lintels that date it 1620: its external staircase leads to two doors, those of the men’s and women’s apartments respectively. Other fine houses are those of: — Cheikh Hassan el Khabbaz in Rue Dahliz el Molk; Osman Agha, at some cross roads, — carved wood inside, date 1808; Ahmed Agha in the Chareh el Ghabachi to the west of the town, invaded by sand.

At the end of the main street is the most important building in the town, the Mosque of Zagloul. It really consists of two mosques: the western was founded about 1600 by Zagloul, the Mamaluke or body-servant of Said Hassan; the other and more ruinous section is the mosque of El Diouai. There is a courtyard with fountain in centre. The entire mass measures about 80 by 100 yds. All is brick except the two stone minarets; the ruined one was “cut with scissors” according to local opinion, but according to archaeology fell in the early 19th cent. The sanctuary of the Mosque of Zagloul proper is a stupendous hall; over 300 columns, many of them antique, are arranged in six parallel rows, there are four praying niches, three of them elaborately decorated, there is the tomb of the ex-body-servant himself, now worshipped as a saint and wooed by votive offerings of boats, and, in the tomb, his former master, the Said Hassan, lies with him, and shares his honours. The sanctuary is ruinous and carelessly built, but its perspective effects, especially from the south wall, near the tomb, are very fine and rival those of the Mosque of El Azhar at Cairo. Light enters through openings in the roof.

East of the Mosque of Zagloul and close to the river is the Mosque of Mohammed el Abbas, date 1809, of superior construction but on the same style; it has, unlike the other mosques of Rosetta, a fine dome, covering the tomb of the saint.

Other Mosques: — Toumaksis Mosque, built by Saleh Agha Toumaksis in 1694; it is reached up steps; fine iron work round the key holes; there is a good pulpit inside, also tiles, and the prayer niche retains its original geometrical decoration of hexagons and “Solomon’s seals.” — Mosque of Cheikh Toka, which stands in an angle of the Chareh Souk el Samak el Kadim; portal in “Delta” style with rosace over its arches; inside, pulpit dated 1727.

About a mile to the south of the town, best reached by boat, is the Mosque of Abou Mandour, a showy modern building, well placed on the bend of the river bank, and backed by huge sand hills that threaten to bury it, as they have buried Bolbitiné.

North of the town, and half-way between it and the sea, is the site of Fort St. Julien, which Napoleon’s soldiers built, and where they discovered the Rosetta Stone. The Fort has disappeared; there is a sketch of it in the Alexandria Museum (Vestibule).

Sailing on the Nile: delightful.