INTERNET LITERATURE, like any other literature, is shaped by general technological developments and by specific social conventions. In the early twentieth century in China, the spread of mechanized printing and the demise of the literati lifestyle conspired to produce a richly varied magazine literature. This literature catered to a wide variety of tastes and was written in an equally wide variety of linguistic and cultural registers, but the many magazines of the early Republican period also had some notable shared characteristics. Most of them reveled in the opportunities the new printing technologies offered for combining textual and visual contents. Photographs, illustrations, and advertisements all played a role in distinguishing different journal styles or genres from one another. The magazine format also helped to continue and strengthen the traditional preference for linking literary production to collective activity. Many journals were affiliated with literary societies or clubs and used their publications as newsletters to stay in regular contact with their members and supporters. Finally, most of them promoted the spread of personal information about authors, encouraging biographical interpretations of literary work, as well as ad hominem criticism. This continued the Chinese tradition of considering text and author as two sides of the same coin (wen ru qi ren) while at the same time laying the foundation for a modern literary celebrity culture.

INTERNET LITERATURE, like any other literature, is shaped by general technological developments and by specific social conventions. In the early twentieth century in China, the spread of mechanized printing and the demise of the literati lifestyle conspired to produce a richly varied magazine literature. This literature catered to a wide variety of tastes and was written in an equally wide variety of linguistic and cultural registers, but the many magazines of the early Republican period also had some notable shared characteristics. Most of them reveled in the opportunities the new printing technologies offered for combining textual and visual contents. Photographs, illustrations, and advertisements all played a role in distinguishing different journal styles or genres from one another. The magazine format also helped to continue and strengthen the traditional preference for linking literary production to collective activity. Many journals were affiliated with literary societies or clubs and used their publications as newsletters to stay in regular contact with their members and supporters. Finally, most of them promoted the spread of personal information about authors, encouraging biographical interpretations of literary work, as well as ad hominem criticism. This continued the Chinese tradition of considering text and author as two sides of the same coin (wen ru qi ren) while at the same time laying the foundation for a modern literary celebrity culture.Following the establishment of the socialist literary system after 1949, both the technology and the social organization of literary production came under state control. Of the hundreds of literary magazines that were in circulation throughout China in 1948 and 1949, not a single one survived the introduction of the new system.1 Instead, the cultural bureaucracy of the socialist state founded a number of nationwide and regional literary journals run by editors appointed by the various branches of the All-China Federation of Literary and Artistic Circles (Zhongguo Quanguo Wenxue Yishu Jie Lianhehui, or Wenlian for short) and its subsidiary, the Chinese Writers Association (Zhongguo Zuojia Xiehui, or Zuoxie).2 Literary magazines became part of a network that also included official literary prizes, financial and nonfinancial benefits and incentives for writers, stipends for editors to travel around the country, distribution via the network of New China bookshops, as well as, specifically in the case of magazines, via the network of post offices. The system whereby readers could subscribe to magazines at dedicated post office counters survived well into the 1980s. All this was part and parcel of the socialist literary system, as described in great detail in Perry Link’s book-length study The Uses of Literature.

During the Cultural Revolution, Wenlian and Zuoxie ceased to function, and literary magazines closed down. For a while, literary production was reduced to carefully selected book publications and the occasional appearance of literary texts in newspapers. The quantity of literary publications gradually increased during the last few years of the Cultural Revolution, in the early 1970s, and periodical publishing recommenced during that time, although the major literary journals of the pre-1966 period did not reestablish themselves until after 1976.3 By the 1980s, the institutions of the socialist literary system were all back in place and literary magazines once again flourished. The 1980s also witnessed the gradual bifurcation between “official” (guanfang) and “nonofficial” (fei guanfang or minjian) literary circuits. As Xudong Zhang has argued, however, the preference of the nonofficial circles for apolitical, modernist writing tied in well with the policy of the Deng Xiaoping regime to promote the autonomy of cultural work in exchange for its depoliticization and noninterference with the overarching course of economic reform.4 The result was that the 1980s avant-garde movement (xianfeng pai) in fiction, widely celebrated by critics for its radical opposition to the socialist realist paradigm, was in fact very much dependent on direct support from the institutions of the socialist system. Professor Shao Yanjun from Peking University has described this paradoxical situation, in which a literary elite used a nationwide support system, designed for distributing mass-produced propaganda literature, to promote instead a kind of literature that could be appreciated only by a tiny minority:

Writers were showing off to editors, editors were showing off to critics, critics were showing off at conferences, and behind it all was the magazine publication system supported by the Writers Association, and the university system. Inevitably, this developed toward cliquishness—and these cliques were not communities of individuals with similar tastes but interest communities of individuals sharing the same privileges. … From the postal system that allowed the free sending of manuscripts for submission, to the patronage of and generous instruction to writers by the editors of the big magazines; from the formal establishment of culture bureaus at prefecture level to the assistance with revising manuscripts, free travel and lodgings provided by the big magazines, the whole emergence and development of the avant-garde movement relied on the latent continuity of the traditional literary mechanism.5

In her influential 2003 monograph The Inclined Literary Field, Shao describes how, when literary magazines were weaned off state support from the late 1980s onward, the literary elite was ill equipped for assuming leading positions in the emerging literary marketplace because its previous cliquish behavior and its denigration of more mainstream and popular work had alienated it from the tastes of the wider reading public.6 Without state support, the 1980s avant-garde collapsed, and the kind of “economic world reversed” described by Pierre Bourdieu as typical of European literary communities never developed in China. Instead, the literary field tilted toward the side of economic capital, with the frantic production of best sellers (chàngxiaoshu) balanced out only by the steady popularity of traditional realist “long sellers” (chángxiaoshu).7 It was against this background of typical postsocialist uncertainty, with familiar institutions disappearing, market mechanisms kicking in, and traditional tastes lingering, that Internet literature began to emerge.

The noticeable commercialization of Chinese literature in the 1990s was the outcome of two simultaneously occurring processes. One was the withdrawal of state support for the literary system already just mentioned. The other was the relaxation of state control over publishing houses and the rise of what is generally referred to as the second channel (er qudao) of semiofficial, market-driven print production.8 The second channel, studied in detail by Shuyu Kong in her book Consuming Literature, is “a grey area of publishing that … includes both unofficial publishing and private book distribution” and that “represents the most commercialized and liberated area of book publishing and distribution.”9

The phenomenon of private distribution of books and journals emerged in the early 1980s and was initially associated with the sale of illegal printed material, including pornography. During the 1990s, partly as a result of repeated government campaigns and a nationwide reregistration of publishing houses, as well as decreasing state control over printing and distribution, a workable system was forged in which state-owned publishers collaborate with private entrepreneurs, with the former providing access to formal “book license numbers” (shuhao) and the latter doing most of the work in terms of production, marketing, and distribution.10 The outcome so far has been that the number of official publishing houses in China has remained stable at around five hundred, but the number of private companies involved in producing books and journals is many times larger. At times the distinction between the state-owned and the private elements is not obvious, especially as the official publishing houses themselves have begun to adopt corporate business models. Changes in this area continue to the present and are reflected, for instance, in Xin Guangwei’s authoritatively comprehensive overview of publishing in China, where he states, in one and the same section of his first chapter, that “all publishing houses in the Chinese mainland are state-owned,” only to correct himself a few pages later to say that, since Liaoning Publishing Group was listed in the stock market in 2007, “gone are the days when all publishing houses in China were state-owned.”11

Especially relevant to the present discussion is Shuyu Kong’s analysis of the main differences in private-sector publishing between the 1980s and the 1990s. After pointing out that, in the 1990s, state sector and private sector became more integrated, she goes on to say that second-channel publishers of the 1990s were “better educated” and produced “better books.”12 As we shall see in later chapters, the expectation that publishers and editors in the private sector, including those operating online, are professionally trained and have certain qualifications is part of the conditions under which private publishing ventures can obtain business licenses from government regulators. These policies undoubtedly raise the level of publications, but they are also meant to discourage the second channel from getting involved in projects that move beyond state-sanctioned boundaries of “healthy” content. Nevertheless, as Kong’s study convincingly demonstrates, the introduction and semilegalization of the second channel has created a vibrant publishing climate, and market incentives can at times encourage cultural entrepreneurs to push the limits, or be instrumental in shifting them.

In the conclusion of her study, Kong turns to the recent emergence of online literature and asks the question if the Internet is providing “a new literary space.” She gives an excellent summary of the development of the major literary website Rongshu Xia (Under the Banyan Tree, http://www.rongshuxia.com), which will feature in my discussion later in this chapter as well. She notes the site’s rapid development toward a commercial business model, which leads her to the following gloomy observation, worth quoting at length:

On the surface, the Internet promises a democratic zone where everyone has the right to freely produce and publish, ignoring literary conventions, political censorship, and not least the prolonged and cumbersome publishing process. However, most objective observers would conclude that up until now, cyberspace has remained a huge virgin territory untouched by deep passion, originality, and talent. Anyone who browses through the gigantic database of literary works stored on Banyan Tree’s site would agree with those critics who decry Internet literature as, at best, simply a form of “literary karaoke” for self-entertainment and, at worst, “literary detritus” freely and copiously discharged onto the screen. The subject and style of these works tends to be narrow, trite, and monotonous, full of conventional and clichéd expressions of predictable personal sentiments. Although traces of unique style and language can be found in certain individual works of Internet literature, in general one must search hard to find any literary innovation. Rarely are the new technological possibilities of the medium, such as the potential for interaction between visual images and words, and the ability to link back and forward between pages, fully explored.13

As I will argue in the next chapter, I do not believe that multimedia and hypertext are the only means of literary innovation on the Internet, and I am less pessimistic than Kong about PRC authors’ ability to create new literary conventions online. More important, however, it is worth noting a slight but significant contradiction in Kong’s argument. The well-known modernist aesthetic that she favors (depth, originality, talent) is intimately linked to the ideals and conventions of an established professional print culture community in which authors, editors, proofreaders, designers, illustrators, and publishers spend large amounts of time polishing and perfecting literary texts meant to be presented as works of art. It is not feasible to expect online literature to have developed such an “art world”14 within the space of just a few years, nor is the Internet the kind of environment where one would expect such an aesthetic to develop. In some ways, Chinese Internet literature is reminiscent of the often hastily produced work that featured in the countless literary supplements of newspapers during the Republican period, which one scholar has aptly described as “literature in its primary state” (yuanshengtai wenxue).15 In other ways, it is quite simply something new to which old value systems might not apply.

In short: it is worth pointing out that a new literary space does not necessarily need to be a new space for “high” literature in the traditional sense. As we shall see in chapter 3, the rise of online genre fiction is a tremendously important new development in PRC literature, even if it means flooding the Web with pulp. In my view, there can be no question that the Internet does provide a new literary space and that it has established and will continue to establish its own conventions and values, which are not identical with the conventions and values of print culture, even though all kinds of intriguing forms of overlap between print media and digital media are in existence. In the following, I provide an overview of the early history of Chinese-language Internet literature. Following that, I give a brief description of the way in which Internet literature forums operate and introduce some of their conventions and the related terminology. This is followed by a more detailed look at the Banyan Tree site, which stands out among PRC online literature portals of the early period. Finally, I give a brief case study featuring Lu Youqing’s work “Date with Death,” which propelled Banyan Tree and online writing to nationwide popularity in the year 2000.

Chinese Internet Literature: Early History

The earliest Chinese-language web literature was produced outside China. As scholars and critics are starting to write the history of this new form of Chinese literature, there seems to be an emerging consensus that the first works of Chinese web literature appeared in the online journal Huaxia wenzhai (China News Digest—Chinese Magazine, hereafter HXWZ), established by Chinese students in the United States in 1991, which was also the world’s first Chinese electronic magazine.16 The magazine was distributed through various electronic channels (LISTSERV, FTP, e-mail) prior to establishing a web presence in 1994. The last issue, number 939, appeared on April 18, 2009. Right from the start, issues of HXWZ included literary writing in various genres, both original writing by contributors and republications of printed work by well-known authors. U.S.-based Chinese students also posted their creative writings to the Chinese-language newsgroup alt.chinese.txt, founded in 1992.

The earliest Chinese-language electronic journal devoted entirely to literature was the monthly Xin yusi (New Spinners of Words), launched by Fang Zhouzi in 1994 and named after the famous independent Republican-period journal Yusi, which was founded by, among others, the brothers Lu Xun and Zhou Zuoren. New Spinners of Words was originally distributed via alt.chinese.txt, with back issues available on various FTP sites. In October 1997, it established its World Wide Web domain, http://www.xys.org, where it continues to be published every month. Other influential literary publications founded in the United States around the same time and mentioned in all histories of Chinese Internet literature are Ganlanshu (Olive Tree, http://www.wenxue.com) and Huazhao (Cute Tricks, http://www.huazhao.com), both launched in 1995. Cute Tricks is said to have been the first Chinese-language literary publication to obtain its own domain name and ISSN number. It is also noticeable because it focused mainly on literature for and by women. Olive Tree, cofounded and edited by the poet Ma Lan, has been praised for its professional user-friendly design, which included in-site search functions that would not become commonplace on the web until much later.17 Both sites are no longer active. Olive Tree has been archived by the IAWM, whereas an archive of Cute Tricks survives at the URL http://www.huazhao.org/huazhao.php.

The year 1995 also saw the appearance of Bulletin Board Systems (BBS) on servers at universities in mainland China, starting from Tsinghua University in Beijing and quickly spreading elsewhere. According to Ouyang Youquan, some original literary works were distributed via BBS, but the main trend was to copy works from Taiwan. Three years later, the first online work to become a print best seller in China also came from Taiwan. Using the pseudonym Pizi Cai (Ruffian Cai), a Taiwanese man called Cai Zhiheng serialized the novel Di-yi ci de qinmi jiechu (First Intimate Contact) on a BBS in 1998, when he was still a graduate student at National Cheng Kung University. First Intimate Contact is a popular romance novel dealing with the world of online dating and virtual romance, written in what had by then become a recognizable “online writing style”: colloquial language broken down into many short segments.18 In that same year, the printed version of the novel became a best seller in Taiwan, while the online version became hugely popular among Internet users in mainland China.19 A year later, a simplified-character edition appeared in print in mainland China and also became an instant best seller, familiarizing many readers with both web literature and cyber culture and paving the way for the web literature craze that was to follow.

Discussion Forums

A very important technological development facilitating the boom in online writing that took place toward the end of the previous millennium was the emergence of interactive discussion forums (also known as message boards, Chinese luntan) on the World Wide Web. Although initially still frequently referred to by the old term BBS, forums are in fact quite different from the old bulletin boards. Forums are web based, feature nice-looking graphic interfaces, and make it very easy for users to generate content. Although in recent years literary forums have had strong competition from literary blogs, forums remain widely popular because they have strong community functions. Whereas blogs typically feature content created by one individual, with other users able to generate only comments, forums typically allow all members of the community to submit their own writing as well as discuss that of others. As will become evident in later chapters, the popularity of forums is showing some signs of waning in China, but they continue to be at the heart of both noncommercial and commercial online publishing, such as the genre fiction websites discussed in chapter 3 and the writings of Chen Cun treated in chapter 2.

Most literary websites host forums devoted to specific genres or themes, often also including classical-style writing, which is undergoing a remarkable revival online. Most discussion forums operate on the principle that only registered members of the site can upload their works to a forum, but that both members and nonmembers can read the works and comment on them. Comments on a particular work are automatically appended to the work itself, creating so-called threads of discussion, which often also involves the author of the original work. This aspect of direct interaction between author and reader constitutes the main distinction between web literature and printed literature in China.

Discussion forums normally appear on-screen as a list of thread titles (zhuti or biaoti). The title of a thread is identical to the title of the post (tiezi) that started the thread. Apart from the thread title, the forum content list normally provides the (pen) name of the author of the original post, followed by some additional statistics, usually the number of hits (i.e., the number of times the thread has been accessed by users), the number of responses or comments, and the date, time, and author of the latest response. In most cases, threads that received recent responses are at the top of the list, and as long as new responses are added, they will continue to receive attention. Once a thread has been pushed off the front page, it tends to be no longer read or discussed, but it will continue to be available for a long time: these works require relatively little server space, and some literary discussion forums have online archives containing literally millions of works.

Most discussion forums are overseen by moderators (banzhu), who ensure that works are submitted to the appropriate forums and, if necessary, delete inappropriate or unwanted content, including content that might catch the eye of Internet censors. As is the case with online communities all over the world, including popular non-Chinese sites such as Facebook, moderators on Chinese sites have access to word filtering software that helps them to identify unwanted content, and some communities are more restrictive than others in this respect. How such filters are used to enforce state regulations, such as existing obscenity legislation, and how they are routinely circumvented, is discussed with reference to fiction in chapter 3 and with reference to poetry in chapter 4.

Originally online forums allowed for members to see their contributions on-screen almost instantly, but many moderators now take a more cautious attitude and will screen postings before they are displayed on the forum. Moderators are also responsible for keeping a forum lively and active, for instance by organizing competitions or suggesting specific topics for writing, and by taking an active part in the various discussions. Many sites operate a system whereby community members gain points for making regular contributions, which add up to their popularity (renqi) rating. As with most online communities, literary forums usually allow members to create virtual identities that include not only pseudonyms (screen names) but also visual information in the form of avatars that accompany each post. The use of real names is unusual, although normally an existing e-mail address is needed in order to complete member registration.20

Moderators are often also involved in selecting the best of the very many works that are posted to the forums for inclusion in special online publications known as webzines (wangkan). Most literary websites, especially those operated by small groups of like-minded associates, will publish regular webzines to showcase the best writing published on their forums. Such webzines will normally be carefully designed and edited, with a layout similar to printed literary magazines, and be devoid of interactive functions, that is, they are meant only to be read, not to be commented on.

From the late 1990s onward, discussion forums took the Chinese Internet literature world by storm. For many of their users, the forums are not much more than glorified chat rooms or online meeting places, or simply a place to practice writing as a hobby, but more serious sites try to devote themselves to high-level creation, criticism, and discussion. The web has also produced new avant-garde groups, especially in the genre of poetry, providing space for shocking antiestablishment writing that cannot easily appear in print, most famously on the Shi Jianghu (Poetry Vagabonds) website, which brought forth the phenomenon of “lower body poetry” (xiabanshen shige).21 The typical features of Chinese literature forums in comparison with similar English-language forums will be discussed at length in chapter 4. In the remainder of this chapter, I shall focus on one of the earliest and most prominent providers of literary forums, the Banyan Tree site, and its early achievements.

Under the Banyan Tree

Founded in December 1997 as a personal web page, Under the Banyan Tree has gone on to become, in its own words, “the longest-standing literary website in China, with the most recognizable brand” (guonei lishi zui youjiu, zui ju pinpai de wenxue lei wangzhan), as well as “one of the largest archives of original literary manuscripts on the planet” (quanqiu zui da de yuanchuang wenxue zuopin gaojianku zhi yi).22 This record-breaking online phenomenon, too, has its origins in the United States, since its founder, Zhu Weilian (William Zhu), is a U.S. citizen who moved to Shanghai in 1994. All overviews of the history of PRC Internet literature give Banyan Tree a very prominent place and describe the specific business strategy that underlay its success.23 In 1999, Zhu founded the Shanghai Under the Banyan Tree Computer Company and turned his personal website into a full-fledged online literature portal, billed as “the global website for original Chinese-language works” (quanqiu Zhongwen yuanchuang zuopin wangzhan). Right from the start, Zhu engaged in crossover activities with other media. The Banyan label was linked to literary programs on Shanghai local radio as well as to literary columns in newspapers. It organized literary prize competitions and promoted print publications of book series under the Banyan brand, as well as other joint-print ventures with traditional publishing houses. All this activity soon turned Banyan Tree into “a sprawling multimedia business.”24 The site drew the attention of, and was eventually taken over by, the German publishing giant Bertelsmann, which sold it in 2006, by which time it had lost some of its past luster. In 2009 it was acquired by Shanda Interactive Entertainment, which now owns all major literary websites in the PRC, including the large popular fiction sites discussed in chapter 4. In the “About Us” section of its website, Banyan Tree now presents itself as an “independent copyright trading center” (duli de banquan yunying zhongxin).

Although it is generally recognized that Banyan Tree discovered a number of authors who went on to great literary fame and considerable critical acclaim (most notably Anni Baobei and Murong Xuecun, both of whom had the print publication of their first novels arranged by the site), scholars have generally paid more attention to its commercial success than to its literary characteristics. Important to recognize in this respect is the fact that when the site went public in 1999, William Zhu had brought together an enthusiastic editorial board, with the established author Chen Cun (see chapter 2) as chief artistic officer (yishu zongjian) and general consultant for literary matters. I visited the Banyan Tree site regularly in March 2002, when the takeover by Bertelsmann was on the cards but had not yet taken place, and I noted at the time the editors’ attempts to maintain certain literary standards, as well as the tension between artistic and commercial agendas. The following section is an account of my browsing experiences on the site during that period, which I believe are representative of the characteristics of early PRC Internet literature.

Banyan Tree in 2002

As was and is the case with most Internet community websites, there were in 2002 two ways of entering Under the Banyan Tree: as member or as guest. In order to become a member, one needed to register a username (appropriately called pen name [biming]) and an existing e-mail address. Upon doing this, one would receive an automated e-mail message including a link to a registration page, where one could complete the registration process. This procedure, commonplace nowadays but still fairly new at the time, constituted a simple security measure, ensuring that prospective members did not submit fake e-mail addresses. No other personal information needed to be submitted in order to register, although one could volunteer a real name, age, and location. As far as was able to be observed, the main difference between members and guest users was that only members could submit their own writing to the main bulletin boards and use the related personalized services.

Once one had decided on the method of entry and clicked on the appropriate button, one would arrive at the main page. The main page contained regularly changing links to featured areas of the site. The main navigation bar at the top provided links to the seven main sections of the site. The navigation bar at the bottom of the main page contained a link to a group of English-language pages introducing the website and the company behind it. The page called “Our Footprints” contained more information about the history of the site, stating that it was founded in July 1999 in Shanghai, with a staff of twelve people. “Our Footprints” made specific mention of the fact that Chen Cun opened his own column on the site in September 1999 and officially joined the site as its “CAO” (chief artistic officer) in April 2000.25

While I was carrying out my research in March 2002, Chen Cun’s column was appearing less and less frequently and eventually disappeared on March 28, 2002. Although no reason was given, this event was most likely related to a debate unleashed by Chen in July 2001, when he submitted a much-debated piece to one of the site’s bulletin boards, stating his disappointment with the development of web literature, announcing that its heyday was already over. Though this may have been the case from his perspective (see also chapter 2), the volume of texts added to Under the Banyan Tree was still staggering. In the eleven days between March 17, 2002, and March 28, 2002, when I visited the site on a daily basis, more than thirty-four thousand articles were published on it. From checking the daily additions to some of the sections, I obtained the impression that this was an accurate figure and that it represented only actual literary works being contributed, not the even more numerous responses to those works that other users submitted.

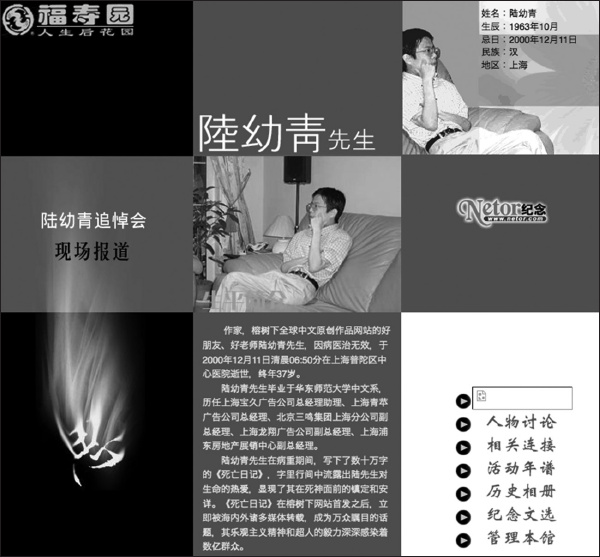

Apart from Chen Cun’s writings, there was another, arguably more important reason why Under the Banyan Tree had achieved such popularity. It published, from August to October 2000, the online diary of a man called Lu Youqing, who was dying of cancer. This unusual event attracted enormous media attention and drew countless users to the site. Although originally submitted through one of the bulletin boards, the diary was later given its own separate area on the site, with parts of the work available in English translation, under the title “Date with Death.” In 2002 I did not do a close reading of Lu’s work but only registered its significance. A discussion of the work, based on a later reading with the benefit of hindsight, is presented in a later section of this chapter.

In March 2002, the rules for submission to Under the Banyan Tree clearly indicated that anyone was welcome to contribute, regardless of location or nationality, as long as the contribution was written in Chinese. The site appeared to be well supported by advertisers, especially by the Chinese branch of the German Bertelsmann Book Club, which sponsored the annual “Bertelsmann Cup” web literature competition, which by then had already been held three times. Apart from those winning prizes in such competitions and from a number of “contracted contributors” (qianyue zuozhe), none of the contributors were paid for their publications.

Already in 2002 it was clear that the company running Banyan Tree was crossing over into other media: collections of works published on the site were available in book form under the Banyan Tree label, and the name of the site was linked to a radio program, which in turn was accessible online through the “Radio Station” (Diantai) section of the site. This section also featured a forum for “texts with sound” (yousheng wenzhang). These were literary texts by various contributors, read out by what appeared to be a professional reader: the same voice was used for different texts. This section was the most experimental, in terms of form, of the whole site. In other aspects, however, the formal appearance of Banyan Tree in 2002 remained indebted to the print-culture paradigm. Texts submitted to the forums were visualized on-screen as if they were typed on lineated paper; Lu Youqing’s diary was visualized as an open book on-screen.

Banyan Tree catered readily to the need for readers to know more about the authors of literary work. There were a few regular contributors to the site who had their own areas, accessible through the “Special Columns” (Zhuanlan) section. These areas contained much information about these authors’ personal lives, as well as links to their writings, pictures of them, and other information they felt eager to share with their readers. One of those areas was devoted to Anni Baobei, who at the time was known mainly to online audiences and not yet the established print author that she is now. The text on the right-hand side of the main page of her section, next to her picture, clearly created the illusion of direct contact between author and reader, as it read, “I write my writings for kindred spirits to read” (wo ba wode wenzi xiegei xiangtong de linghun kan), harking back to the traditional notion of the reader as “soul mate” (zhiyin). The support of her online fan base has played a crucial role in the development of Anni Baobei’s career.26

The opposite phenomenon was also visible, that is, print-culture writers accessing web culture on the basis of already established fame. In the “Writers Columns” (Zuojia zhuanlan) section, accessible through a sidebar menu on the front page of the site, readers could access areas devoted to very established writers such as Wang Anyi, Shi Tiesheng (1951–2010), and Shu Ting, as well as the famous Shanghai-based academic Chen Sihe. These areas normally contained a picture of the celebrity in question, some biographical data, and a full version of one of their works, for which Banyan Tree had obtained the right to republish it online.

Apart from well-known writers or contracted contributors, normal contributors to the website, once their contributions became sufficiently regular, also had the opportunity to share biographical information with their readers. Each of the main channels (fiction, poetry, and essay) in the “Literature” (Wenxue) section of the site contained a subsection called “Stars of the Channel” (Pindao zhi xing), where readers could look for information on some of the frequent contributors to the channel. These biographies were generally much more elaborate than those of the celebrities, containing both pictures of the authors and text they provided themselves, signaling their own eagerness to share this information with their readers.

In 2002, Banyan Tree struck me as being involved in community-building practices not dissimilar to those practiced by the literary magazine communities that were active in China roughly a century earlier.27 The company running the website organized meetings and workshops for readers and prospective contributors, usually in Hangzhou, traditionally the scene of literary gatherings. Banyan Tree had also established at least one literary society, the Under the Banyan Tree Poetry Society, which had its own area on the site, as well as its own online journal, which, once again, was visualized on-screen as if it were a printed publication laid flat on the screen surface. However, what made (and makes) Internet communities like this qualitatively different from print-culture communities was the possibility of almost direct interaction through the various discussion forums. The actual communities were formed on those forums, as authors submitted and published their works and readers (or other authors) commented on them through the website, developing their own critical discourse and values in the process.

There were at the time two distinct types of bulletin board on the Banyan Tree site. In the “Community” (Shequ) section, which was divided into various subsections, members could submit writings on a variety of topics, ranging from ghost stories to classical poetry. Those forums were monitored and writings could be deleted if they contained inappropriate or illegal content. In the “Literature” section, contributions to the various forums for fiction, poetry, and essay were scrutinized by an editor before they were published. Contributors, who must be members, would submit their texts online through the website. Within forty-eight hours, one of the Banyan editors would read it and decide whether or not to publish it, and then communicate the decision to the author’s e-mail address.

In order to check whether the system worked in practice the way it was said to work on the website, I registered as a member and, on March 26, 2002, I submitted to the poetry forum a poem I had written in Chinese. Sure enough, two days later I received an e-mail from one of the editors informing me that, regrettably, my poem had been rejected. Although it was considered “sincere” in its emotions, it was deemed in need of further polishing in terms of the actual expression of the emotions. Interestingly, however, the technology of the website did allow me, as a member, to keep an online record of all the writings I submitted, whether published or rejected, and to put them in my own “online collection,” where my poorly written poem continued to linger for years until it (and my membership status) finally fell victim to a major site overhaul. The fact that even rejected texts remained available to members wanting to access them online must have meant that there were many more texts in the Banyan database than the one million or so that had been published on the forums at the time. In 2002, two years before the founding of Facebook and three years before the emergence of YouTube, such observations of the sheer quantity of data being stored by online service providers and shared by online communities were still very remarkable.

The main conclusion I drew from the story of my own failed debut as a web literature author was that Banyan Tree was serious about its intention to carry out some form of quality control, no matter how massive the quantity of its output might be. This did not mean that the works that did get published were necessarily all masterworks. It did mean, however, that Banyan Tree at the time refused to acquiesce to being part of “popular culture.” From my own readings and observations, I obtained the impression that the majority of writings on the website were creative and original in intent. They did not mean solely to entertain, and the vast majority of contributors did not realize any financial gain. Even though the Banyan Tree company clearly made money from its operations, the thousands who published on the site were predominantly aspiring writers with a pure interest in literature. Their interest was not, however, in a kind of literature that was purely textual in nature but in literature as an act of social communication. As such, they were not just being very postmodern or very popular but also continuing a Chinese cultural tradition, of practicing writing in the context of friendly gatherings, even though the gatherings were now taking place online.

What was especially noteworthy about Banyan Tree in 2002 was its eclectic mix of literary genres. For me at the time this was by far the most innovative element of the site, and of Chinese Internet literature in general. Previously in modern Chinese literature there had been clear-cut distinctions between so-called New Literature, on the one hand, and literature in traditional and popular genres on the other, to the extent that one would scarcely be able to see the products of those three different styles appear in the same space. Literary websites, however, had it all. Banyan Tree had forums for classical poetry, travelogue, and martial arts fiction alongside those for more “serious” or more “modern” genres. The overall impression I took away from the site in 2002 was one of variety and playfulness, none of which could be reduced, however, to specific themes, forms, or formulas, as would be the case with commercial genre fiction. Although Banyan Tree had not become the online equivalent of the leading print literature journal Shouhuo (Harvest), which was reportedly its founder’s original ambition,28 its literary aspirations were undeniable.

Banyan Tree in 2011

Although it still enjoys widespread name recognition, Banyan Tree is now no longer the leading website in the Chinese online literary landscape. Traffic to the site is considerably less than it used to be.29 It still features a very sizable searchable archive of writing, some of it dating back to the founding years of the site and including work by well-known contributors, such as Chen Cun, while other work, such as Lu Youqing’s diary, which used to have its own section on the site, is no longer available. The site also still has its distinctive logo (a green tree) and color coding (again, mainly green). Occasionally the design of parts of the site is reminiscent of the earlier print-inspired visual form. The main menu of the “Novels” section, for instance, appears on the screen as two small lineated pages in a ring binder.

As mentioned, Banyan Tree was recently purchased by the Shanda company, which also owns all the largest Chinese genre fiction sites and provides membership access to all of them with a single ID, called the Shanda travel pass (Shengda tongxingzheng). Like all the Shanda sites, Banyan Tree now devotes much space to the serialized publication of long genre novels, some of them by authors identified as “VIPs,” but unlike Shanda’s more commercial sites, the novels on Banyan Tree can be read freely without subscription. The site emphasizes its ability to arrange for print publication of online work, and the typical career trajectory of the current Banyan Tree authors is clearly visible by looking at the forum lists. Titles carry little logos that indicate their status, moving from jian (“recommended” by the site editors) to jing (chosen as “best of” the forum), then to qian (“contracted” by the site)and to ban (“published” in print). As far as I have been able to ascertain, novels published in print also remain available to read for free on the website.

“Novels” (Changpian xiaoshuo) is the name of one of the three main sections of the site. The second is called “Short Literature” (Duanpian wenxue) and is devoted to short stories, essays, and poetry. The third is called “Rankings” (Paihangbang) and provides access to a wide range of listing methods of all the works in the site archive (zuopinku), the total of which exceeded 1.5 million works in December 2011. Works can be listed by title, by length in characters, by date, by popularity (number of hits per day, week, or month; number of comments), and by status (ongoing, finished, published, unfinished). They can also be grouped by the names of the thirty-odd literary societies (shetuan) for which the site currently hosts space. These societies, some of which date back to the early years of the site, run their own minisites, including dedicated forums, archives, and so on, some of them with access restricted to members.

All in all, Banyan Tree is still a lively literary site and still relatively less commercial than other sites in the Shanda stable. However, it never regained the popularity and attention it enjoyed in its early years, much of which should be credited to the writings of one man, Lu Youqing, to whose work the chapter now turns.

Lu Youqing’s Date with Death

I don’t know about others, but personally I have had this picture of death in my mind ever since I was a child. Over the past few decades, whenever I accidentally came to think about the topic of death, that picture, which now seems to me to be like an oil painting, would come to my mind in a very realistic manner:

Winter. A clear, bright lake. The water in the lake is not very clean, but that is just because the frost has set in. Dark earth. White traces in the distance, possibly snow. Around there are some tall, northern trees. They are lonely because of the frost. …

On the other side of the lake is a European-style house, probably white. Lights are on in each room. The view is unclear. Its huge shadow cast on the surface of the lake, never stirring, making the lamplight appear even brighter.

After a while, the lights go out: one, another one, a third one. … The lights go out slowly but securely, like a ritual. …

When the last light goes out, a person has died.30

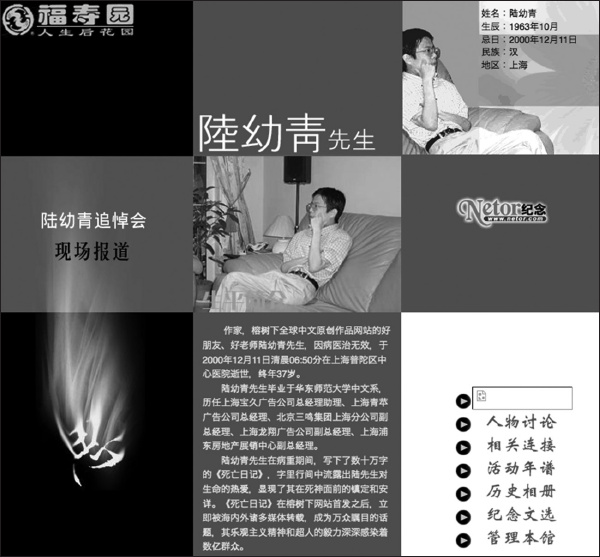

These are the opening lines of a work called “Date with Death,” as they appeared on the Banyan Tree site on August 3, 2000. The author was a man called Lu Youqing, who was a terminal cancer patient determined to leave a public record of the final days of his life. Excerpts of his “death diary” continued to appear online for the next two months, with the final installment appearing on October 23, the diarist’s thirty-seventh birthday. He eventually passed away on December 11, a few weeks after his diary had also been published in book form.31

The publication of Lu’s diary attracted much media attention, to the extent that when he died, it was reported not only in national newspapers but also by the Guardian and the BBC.32 Historians of Chinese Internet literature tend to agree that the success of the diary significantly promoted the reputation of Banyan Tree as the country’s most important portal for online writing.33 The Western media coverage of the event commented on the diary’s unusual outspokenness, claiming that Lu’s writings “have established a new standard for honesty in a society where reticence and considerations of face inhibit frank discussion of illness and death.”34 They also highlighted the author’s criticism of his country’s medical system. Yet apart from the social and medical angles, there are other perspectives from which to analyze this event, which, after all, took place in the literary sphere. What interests me here is the exact manner in which both the online and print publication of the diary were managed by a literary website and what Lu Youqing’s writing can tell us about emerging styles and genres of Internet literature.

I first learned about Lu Youqing and his diary during my visits to the Banyan Tree website in March 2002, almost two years after it had begun publication. I encountered the diary entries all linked to a separate section of the site, away from the common discussion forums, and with some entries available in English translation. My assumption at the time was that Lu had initially been a normal contributor to one of the forums and that the special minisite devoted to his work was an online archive that had been created at a later date. Now, in 2011, this minisite is no longer to be found on the Banyan Tree site. The Chinese text of the diary is still available on many websites and was also resubmitted to the Banyan Tree archive by an anonymous poster in 2001. The partial English translation is, as far as I know, no longer available. Nevertheless, a more careful examination of the minisite as it existed, with the help of IAWM captures, shows that the story of Lu Youqing’s diary is more complex than I originally assumed.

The IAWM captured the front page of the Banyan Tree site on August 18, 2000, just over two weeks after the date of the first diary entry.35 There is a very prominent link to the diary on the site’s front page, and the link is not to any of the discussion forums but to a special section of the site, with the same URL that I first visited in March 2002. The first captured snapshot of that URL in the IAWM dates from October 18, 2000, when Lu was yet to publish his last entry.36 It shows that the minisite, with its distinctive booklike format that I commented on and reproduced in my earlier article,37 was already in place while the diary writing was ongoing. Even the English translations of some of the earliest entries were already there. The page has a link to one of the discussion forums where readers can go to discuss the diary, but the diary itself did not originate on any of the forums.

The main page of the minisite, as captured by the IAWM, links to a number of paratexts, including a helpful introduction by two Banyan Tree editors known as Shouma and AVA, under the title “Zui hou de liwu” (The Final Gift).38 The text explains that the site editors were approached by a woman working for the East China Normal University Publishing House who told them she had a friend who was dying of cancer and wanted to leave a “final gift” to his family in the form of a written account of his final days. The friend wanted to publish these writings on a website and allow readers to comment on them and discuss them, and he had thought of Banyan Tree as an appropriate place to do so. The editors went to visit Lu Youqing the next day, and some further negotiations followed, during which the editors also read parts of the diary already written. Lu Youqing initially asked for a special column called something like “Dying Live” (Siwang zhibo), but the editors considered this to be too “heavy” (chenzhong) and too “cruel” (canku). Instead, they offered to serialize his diary on a regular basis in the “Books and Periodicals” (Shukan) section of the Banyan Tree site, which was a section devoted to the authorized (re-) publication of copyrighted works. They also offered to help Lu Youqing find a publisher for the print publication of the diary. The editors ended the article by explaining that online serialization of the diary would not start until after Lu had granted them authorization and asked readers to keep an eye out for its appearance on the site. In other words, this article was published on the site before serialization of the diary began and was intended to draw attention to the event. When the minisite eventually appeared, it stated clearly that Lu Youqing had granted online publishing rights of the “diary version” (riji ti) of his work exclusively to Banyan Tree and that no other websites were allowed to copy his work.

Judging from the language used, the rights granted by the author were only those to the online diary-style serialization. This would, on the one hand, ensure that Banyan Tree had a unique record, while, on the other hand, enabling the author to grant rights to other, offline publications of his prose elsewhere and to an eventual book publication. Moreover, as becomes clear from another paratext, written by Lu Youqing himself, he only ever published 50 percent of his diary online. This was at the behest of his print publisher: if the full text of the book publication was not available online, the book would be more difficult to pirate.39 This paratext, titled “Gaobie wangyou” (Farewell Online Friends), appeared on the minisite sometime after the last installment of the diary was published and was immediately followed by a piece by Banyan Tree managing director William Zhu himself, in which he pays tribute to Lu Youqing.40

In “Farewell Online Friends,” Lu admitted that the “gift” he had intended to leave for his family was not just the diary itself but also whatever money could be made from it through book sales. At the same time, as is clear from a conversation between Lu and Zhu recorded in the latter’s contribution, the diarist was repeatedly confronted by some representatives of the local media and some online commentators with the claim that he was trying to turn his death into a hype (chaozuo) purely for financial gain. In response to this, William Zhu pointed out that his site was offering the diary to its readers free of charge and without any surrounding advertising. Although Banyan Tree is likely to have taken a cut from profits of the print publication, if indeed they helped arrange it as they had promised, and although the diarist himself, for valid reasons, was not averse to profit, the editors’ refusal to turn Lu’s dying days into a live spectacle and Lu’s own fear of being accused of hyping are indicative of the serious intentions by all concerned. The publication of the diary was a managed media event, but it was managed in such a way as to achieve distinction from other media events and best sellers aimed more unabashedly at capitalizing on the exposure of privacy or the challenging of social taboos. We will come across a similar act of distinction in the next chapter, when Chen Cun draws a clear dividing line between his own diary-like online writings about sex and the “sex diaries” of Muzimei.41

The serious intent of Lu Youqing’s diary is emphasized, both in the text of the diary itself and in the paratext, by means of association with the concept of “literature” (wenxue). William Zhu’s piece, which recounts a meeting with Lu Youqing, states that literature was always their favorite topic of conversation, whereas Lu refers to himself in the diary as a “young literature enthusiast” (wenxue qingnian).42 In the following lines from the first entry of the online diary, dated August 3, 2000, Lu Youqing places his work quite pertinently in a literary context by discussing his choice of genre, while once again mentioning its lack of commercial potential. In doing so, he harks back to age-old Chinese literary concepts of sincerity and realness.

Why do I use the diary form? I thought about that. I could not possibly produce a scholarly essay [lunwen]. Of course I could have chosen some literary prose or essay form [sanwen suibi], but I figured since my life is set to become unhappier with every passing day, I might easily end up shunning [the writing] altogether. A diary is better, because it is like a time card: it shows you straight away how hard someone’s been working. And anyway, in a diary you can still write scholarly essays, or even poems, and a lot more stories about yourself. Unfortunately my private life won’t sell at the box office.

Diaries have another advantage: they are real [zhenshi]. It is hard to fake this kind of writing. Indeed, nobody in the kind of state that I’m in could feel the need to say anything fake.

It’s real, that’s why it’s valuable [zhenshi, jiushi jiazhi].

This is immediately followed by a statement of his reason for choosing Banyan Tree as his preferred platform, which echoes the same values.

I thought long and hard before choosing Under the Banyan Tree as the first publication outlet for my diary. I felt that the style and aim of this website matched my intentions. More important, its members are not like those netizens who are only after “rankings” or “prizes.” They are thoughtful people [sikaozhe de ren]. I should like them to be the first to see my writing, and I hope they will chime in and respond. I am really looking forward to reading their comments.

In various places in the diary, Lu writes about the significance of the online interaction with his readers at Banyan Tree. Although he was apparently unable to respond much to readers’ comments, because he was in too much pain and discomfort to write more than the diary, he occasionally includes responses in the diary entries themselves. On August 13 he notes that his writing is starting to attract more and more attention, not only from the media but also from Banyan Tree members, who are leaving responses and comments. He expresses his gratitude and affection for those readers, some including old friends and classmates he had not heard from for a long time. In the same context, he comments on the time-sensitive nature (shixiaoxing) of diary writing. It needs to be “fresh” and “real” in order to be convincing. He assures his readers that, although adjustments to the dates of his diary entries are made for “technical” reasons, all that he publishes is recent and new. He does not expand on the technical reasons other than that they are “inherent” to the characteristic nature of websites and newspapers. Presumably his entries were first read and where necessary adjusted by editors before they appeared on the website.

A third observation about reader response to his writing included in the same entry of August 13 is that he hopes that readers will pay more attention to the written words and less attention to the person writing them. Once again, it is clear that he does not wish the serious nature of the topics he writes about to be undermined by excessive attention to his background and personality. This is the basic aspiration of most traditional literary writers and another indication that Lu Youqing wanted to differentiate his work from that of celebrity authors. The debate about Wei Hui’s Shanghai Baby, which dominated the cultural media that same year and led to the novel’s being banned, is likely to have been a relevant context.43 In any case, it is clear that the development of the content of this online work was driven at least in part by direct reader response.

This becomes even clearer when, a little over a week later, in the entry dated August 21, Lu refers to reader response again to explain why he is starting to write about his childhood and his family. It is because many readers have expressed the wish to understand him better and know more about him. In this case, moreover, he refers to the readers as “friends” (pengyou). As we have seen in the case of Anni Baobei’s section on Banyan Tree, the idea that the reader is a kind of soul mate or friend and, conversely, that there is a need to provide readers with personal information about the author so that author and work can be better understood is part and parcel of a very traditional Chinese view of literature. The result in this case is some tension between, on the one hand, the author’s desire to discourage unsympathetic or critical readers from invading his privacy or casting doubt on his serious intentions and, on the other hand, reaching out to friendly readers and sharing personal information with them. A similar kind of tension is also inherent in the diary as a literary genre: it is private writing for public consumption. Throughout “Date with Death,” Lu Youqing does not just record his thoughts and feelings, as all diarists do, but also explains himself to a readership of which he is keenly aware.44 Moreover, in the parts where Lu writes about his parents, or about his student days, his writing is more akin to the genre of autobiography, although he usually manages to forge some sort of link to the present. (For instance, after having written about his siblings, he comments on the fact that the generation of only children born after the introduction of the one-child policy will never know brotherly and sisterly love and friendship.)

A very special implied reader of the diary is the author’s daughter. She was eight years old at the time, and Lu Youqing states repeatedly that he hopes she will eventually get to read his writings, when she is older and he will already have passed away. (Cynical commentators suggested that he could have achieved this without publishing his work.) One of the most moving entries in the diary is that of September 18, when Lu records five “family precepts” (jiaxun) addressed to his daughter. He prefaces the precepts with a description of himself as a “traditional Chinese father” who wants to have a say in his daughter’s choice of marriage partner. The precepts are meant as instructions to guide her toward choosing the right man. The way he lists and numbers his instructions (“Family Precept One, Family Precept Two,” and so on) carries a hint of irony and self-mocking, but with much understated emotion, culminating in the short and simple final precept: “Just do what your mother says” (Mama shuo le suan).

Yet this part of the diary, too, appears to have come about at least in part as a result of reader response and editorial intervention. On September 7, Banyan Tree’s chief artistic officer, the author Chen Cun, published a short prose piece on the site titled “At the West Garden Hotel.”45 In the piece, he recounts a trip to Yangzhou for the recording of a TV talk show titled “Tell It as It Is” (Shi hua shi shuo), in which both he and Lu Youqing, his wife, and daughter appeared as guests. In simple words, Chen Cun paints his impression of the Lu family. Toward the end of the piece, he expresses regret for not having had the opportunity to ask Lu Youqing a question that had been on his mind: what would he like to say to his daughter? He elaborates by saying that any words that Lu were to leave behind for his daughter would constitute the most solemn advice (zui zhengzhong de zhufu), something that would accompany her throughout her life. It is likely that this very special response to his work by an established prose writer encouraged the diarist to record his “family precepts.”

The clearest case of reader-response impact on the progress of the diary appears in the entry for August 30, when the diarist explains that his decision to write about his college days and comment on college experience in general resulted from discussions during a special online chat session with Banyan Tree readers a few days earlier. No such prompting was required, however, for the passages where Lu chronicles, sometimes in meticulous detail, the deterioration of his physical condition and his rational and emotional responses to that process.

The diary entry of August 10 deals with the author’s physical condition through a classic mirror scene. After mentioning how much weight he has lost in five years of illness, Lu writes,

The me in the mirror is starting to look more and more like a flat specimen. The only thing that stands out is the tumor on my neck. It has taken a year for it to grow beyond the size of a tennis ball. (That tennis ball is going to be the death of me.) Once as I was standing in front of the mirror I burst out in tears. I felt I should not have become like this. I hated my own flesh. More recently, I have learned to accept the facts.

Despite his frequent use of dry understatement, as with the sentence in parentheses in the quoted passage, there are understandably plenty of passages in the diary expressing bitterness and anger. Lu rarely indulges in self-pity and more typically chooses to revert to using humor with a tinge of self-deprecation to balance his negative emotions. In the entry for September 14, he discusses the effect of recent weather (successive typhoons) on his condition:

[The] clouds and rain and the sudden changes in air pressure that come with the typhoons are making it very hard for me to get through the day. This mixture of depression, wound pain, and oxygen deprivation can barely be put into words. I get angry at times, thinking that if those typhoons keep messing with me, I’ll buy myself a plane ticket out of here. I don’t care where I’ll go, as long as there is sunshine, no crazy winds or rain clouds, and plenty of oxygen.

But the planes were grounded as well.

On September 24, another rainy day, Lu wrote an exceptionally funny and cheerful piece in response to the Chinese women’s football team’s elimination at the Sydney Olympic Games (they where eliminated at the group stages following a 2-1 loss to Norway on September 20). In the entry, he elaborates on the idea that Chinese athletes’ performances are badly affected by the weight of serious expectation on their shoulders. They are perceived as, and perceive themselves as, fighting for the glory of their nation and, as a consequence, they lack enjoyment in their sport. Success and good fortune, he writes, come to those who smile and are happy. “Sports fans throughout the country, myself included, should all agree that at the next match we won’t be shouting ‘Come on!!’ but we’ll be shouting ‘Cheese!’” He goes on to develop this point into a critique of Chinese people in general: “Is it really that hard for Chinese people to be happy?”

Commenting on the state of China and its people has been a common trope in modern Chinese writing, but it is nevertheless surprising to see it pop up in this kind of private chronicle. Lu himself comes to this realization a few weeks later in the October 4 entry, in which he discusses modern China’s obsession with “science,” only to end with the comment, “There is a lot more left to say, but I guess for a seriously ill person to discuss affairs of the state might come across as somewhat eccentric [jiaoqing].”

One of the most detailed descriptions of his illness appears toward the end of the diary, on October 10, accompanied by an explanation of his reasons not to write about the specific state of his illness too often:

My physical condition is getting worse and worse these days. The tennis ball on my neck has turned into an Olympic shot put ball. There are now also a bunch of tumors of different sizes on my chest, which are diabrotic, so I never feel clean and dry. …

The weirdest thing is that my appetite has improved. I guess the cancer cells have entered adolescence?

Sometimes I think, who cares, I’ll just eat whatever I want. But those little buggers are blocking my throat. I even choke on tofu.

You really don’t need ink to record the life of a sick man. The feelings themselves are black enough.

The most common way to express concern for a patient is to ask how they are doing. But what the patient fears most of all is his own condition, which is why I write as little as possible about it in my diary. Regular updates like this one are meant as responses to the concerned inquiries of countless friends.

On October 23, Lu Youqing announced the end of the diary, writing the last entry on his thirty-seventh birthday.46 The last piece typically consists of some reminiscences of past birthdays, a general discussion of Chinese people’s changing perception of birthdays in general, and a critique of the younger generation’s obsession with celebrating birthdays. But he ends on a brief personal note, barely clinging to his usual understatement. These are his last lines:

My last birthday has come. I’ll be going now.

There are so many junctures in a person’s life. Of course I can’t bear it, but I really don’t dare to dwell on a moment like this, and I am even more afraid of thinking about it too deeply.

Because if I did, my heart would go to pieces.

Commemoration and Legacy

After Lu Youqing’s diary had stopped appearing, Banyan Tree published a few more updates on his situation written by his wife, Shi Muyan. Only one more piece written by Lu himself appeared, under the title “Farewell Online Friends,” as one of the paratexts on the minisite. The piece is not dated but appears to have been written shortly before his death, just after the publication of the book version of his diary. In it he expresses the significance of his experience of online interaction, friendship, and moral support during the period that he wrote the diary, thanking some of his closest online friends by name. He comments positively on the Internet’s ability to connect people and concludes by saying, “If people really have a soul, then I am convinced that contact between this world and the netherworld will be first established through the Net.” Although such direct communication was to my knowledge never established, Lu Youqing had a significant “afterlife,” both online and in print.

The writings of Lu Youqing, who eventually died on December 11, 2000, touched many readers. From the front page of the minisite for his online diary, when it was still online, one could follow a link to an “online memorial” for him, located on the website http://cn.netor.com, which specializes in online memorials. Sponsored by Under the Banyan Tree, this online memorial, which is still in existence, contains pictures of Lu Youqing, information about his life, and links to websites related to him.47 (There is also still a link to the old URL of the minisite, which obviously no longer works—an indication that the memorial is now no longer maintained.) The main section of the memorial is an online forum where readers can leave comments, wishes, prayers, and the like in memory of Lu. When I visited the memorial on March 28, 2002, more than fifteen months after Lu’s death, the forum contained 18,647 messages, 8 of which had been submitted that day, showing that he was still being read and remembered. In fact, when earlier in March 2002 I visited the ranking of “Top Memorials” on the Netor main page, I found that Lu Youqing’s memorial was ranked second, eclipsed by only the memorial for Wang Wei, the fighter pilot who was killed in the collision with a U.S. spy plane in March 2001. Nowadays the memorial is of course ranked much lower, and very few messages have been left in recent years. The memorial also has a section devoted to relevant writings about Lu Youqing, most of which date from the period around 2000–2001, with one notable exception: a short commemorative piece written by his daughter, Lu Tianyou, dated March 2007.48

After Lu Youqing’s death, Chen Cun and others linked to the Banyan Tree website set about publishing the diarist’s posthumous literary work, consisting of one novel and a collection of short stories, none of which had been published before. The two books eventually came out in the summer of 2001.49 As explained by Chen Cun in a text titled “Lu Youqing’s Literary Dream,” copied onto Lu’s memorial site, the manuscript of the novel had been privately printed, but not published, by Lu himself, whereas the manuscript of the stories had existed only in handwriting. The editors corrected writing and typing mistakes and punctuation errors but had otherwise left the texts unchanged and in some cases unfinished. Although the swift publication of these books was, to my mind, clearly intended to capitalize on the interest in Lu Youqing before it would dwindle, it seems it was all done tastefully and without much of hype. The books do not appear to have attracted much critical attention.

Lu Youqing’s writings not only affected readers but also inspired other writers and arguably created a new genre. On one of the bulletin boards of the Banyan Tree site, other diary-like publications involving disease, suffering, and moral issues were appearing when I visited the site in March 2002. One of these was the online diary of Li Jiaming, titled “Zui hou de xuanzhan” (The Last Declaration of War). On March 28, 2002, the thirty-second installment of this diary had just appeared ten days earlier. During those ten days, it had been visited a total number of 38,632 times and, to quote a more meaningful and reliable number, 417 readers had written comments on it. The twenty-ninth installment of his diary had been visited more than 100,000 times, with more than 1,000 readers leaving comments.50

Li Jiaming is a person living with HIV/AIDS, which he claimed to have contracted from a prostitute after a drunken night out. Although some critics doubted, in comments posted on the bulletin board, the veracity of his story, most responses were sympathetic and created an ongoing discussion not only about HIV and AIDS but also about prostitution and alcohol abuse.51 My impression that texts like this were turning into a genre was based in part on a passage in the very first installment of Li Jiaming’s diary, published on August 16, 2001. In the passage, Li carried out an act of distinction vis-à-vis Lu Youqing, saying, “This is not a death diary [siwang riji, i.e., the alternative Chinese title of Lu Youqing’s work]. I do not have time to show off my eccentricity [jiaoqing], nor do I want pity.” Immediately after that, however, he literally quoted Lu (though without acknowledging it) by saying that his actions and writings were meant to call for society’s better understanding of people who suffer from the same disease. In other words, Li Jiaming subscribed to the main function of the kind of writing that he and Lu practiced but at the same time added to its variety by distinguishing his own work from that of his predecessor. This is exactly the way in which genres come into being.

For understandable reasons, when Li Jiaming first contacted them about publishing his writings, the editors of Banyan Tree made a point of checking Li Jiaming’s credentials, including his medical records, before they agreed to let him contribute to their “Prose Essays” (Sanwen) forum. As Li started to attract media attention, he was repeatedly challenged to verify his situation, to the extent that China Central Television had his blood sample independently tested for the HIV virus before they went ahead and interviewed him. Unlike Lu Youqing, however, the AIDS sufferer kept his real identity hidden. (Li Jiaming is a pseudonym.) When a collection of his “notes” (shouji)—the term he preferred over Lu Youqing’s “diary” (riji)—appeared in print in 2002, it was given the subtitle “Online Notes by Li Jiaming, China’s Most Mysterious Aids Patient.”52 During the television interview he apparently had his face obscured. When he received a special literary prize for his work from the Barry and Martin’s Trust in 2003, it was given so little publicity that online commentators accused Li Jiaming, who wrote about it in his notes, of making the whole thing up. (The awarding of a “Barry and Martin’s Literary Prize” of one thousand pounds to Li Jiaming is mentioned only in the trust’s annual accounts for 2003 but not in the actual text of the annual report, nor on the trust’s website.53) Li Jiaming continued to publish new notes irregularly on Banyan Tree until 2005, when he published his fiftieth and last note. All his writings can still be found in the Banyan Tree online archive.

As pointed out by Haiqing Yu, Li Jiaming also founded his own online community and discussion forum.54 That forum (http://jiaming.clubhi.com) was last archived by the IAWM in December 2006 and is no longer in existence. Li Jiaming moved on to another website, http://www.2008JiaMing.com, named after his stated aspiration to stay alive and active long enough to see the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Although at this writing (January 2012) the front page of that site, which is devoted entirely to information about HIV/AIDS, has been hacked, other pages are accessible, including a special section devoted to writings by and about Li Jiaming. That section includes a fifty-first episode of his “Last Declaration of War,” published in 2008, as well as an update on his situation dated April 2010.55 On the site’s discussion forum, readers are occasionally kept updated about his well-being. The site is also used to market his 2002 book publication to help raise funds for his continued treatment.

In a widely available prose piece titled “Li Jiaming: My Life with AIDS,” apparently written in 2009, Li looks back at almost a decade of AIDS activism under his pseudonym. Like Lu Youqing in 2000, Li in this piece also creates a mirror scene:

Faced with myself in the mirror, I sometimes don’t know who I am.

An AIDS virus carrier called Li Jiaming?

A son seeking to atone for his sins, hoping to protect his mother at all cost?

A busy nine-to-five worker in a company?56

To the best of my knowledge, Li Jiaming is still alive at this writing, and his true identity remains unknown.

Online Literature: Emerging Practices

To assess the significance of the temporary fame achieved by online chroniclers like Lu Youqing and Li Jiaming it is important to bear in mind that they were active well before the rise in popularity of online blogs. The technology allowing individual users to construct their own minisites devoted to their own writings, to which readers can comment, was scarcely available in China at this time and did not become widespread until the establishment of the Sina blogging portal in 2005. Since the technology became available, the distinction between blogs and forums has become less clear-cut, since some blogging sites, like forums, are run by communities devoted to the discussion of specific topics or practicing specific styles. Generally speaking, however, blogs tend to be driven by the publication of new content, to which readers respond, whereas forums are driven by ongoing discussion in the thread format. What Banyan Tree did when it decided to publish Lu Youqing’s diary in the form of a minisite was perhaps to create a blog avant la lettre. More important, to my mind, is that the creation of the minisite symbolically raised Lu Youqing’s writings to the level of the site’s “Special Column” authors, on a par with Chen Cun, Anni Baobei, and others considered important enough to have independent sections devoted to their work. This status came with the privilege to publish outside the normal discussion forums, that is, to have one’s texts separated from discussion of those texts. As we have seen, in the online context the removal of commentary and interactive functionalities often represents a form of canonization and a first step toward print publication.