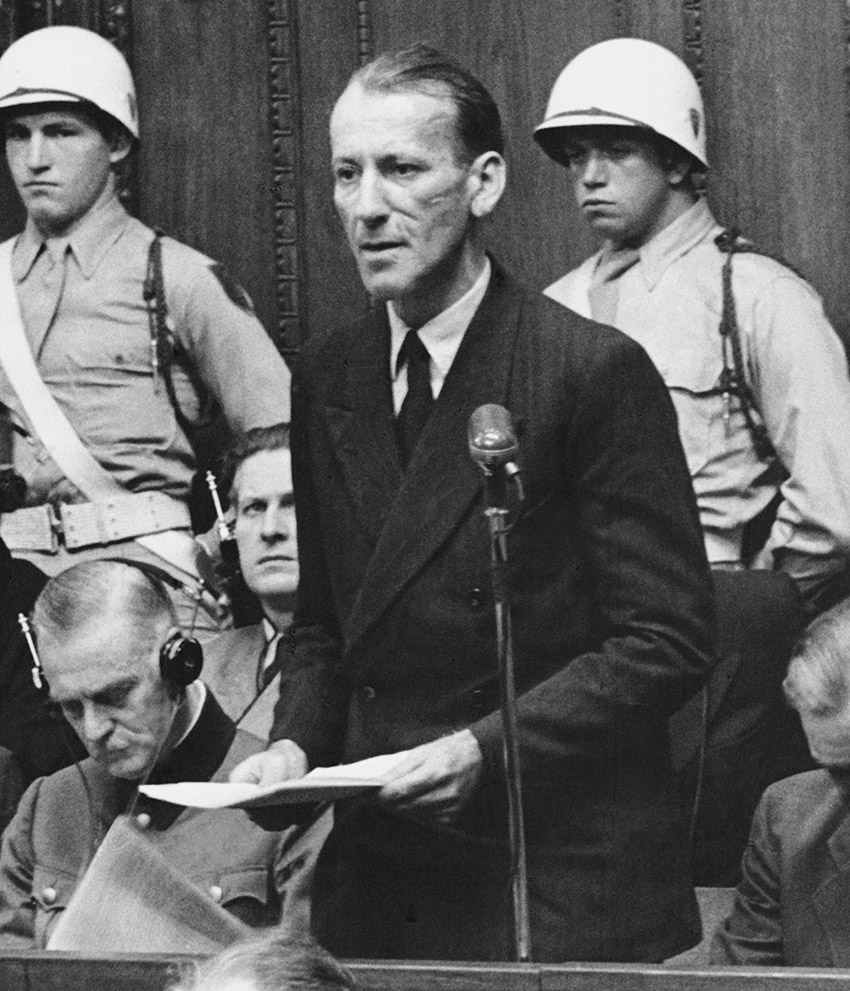

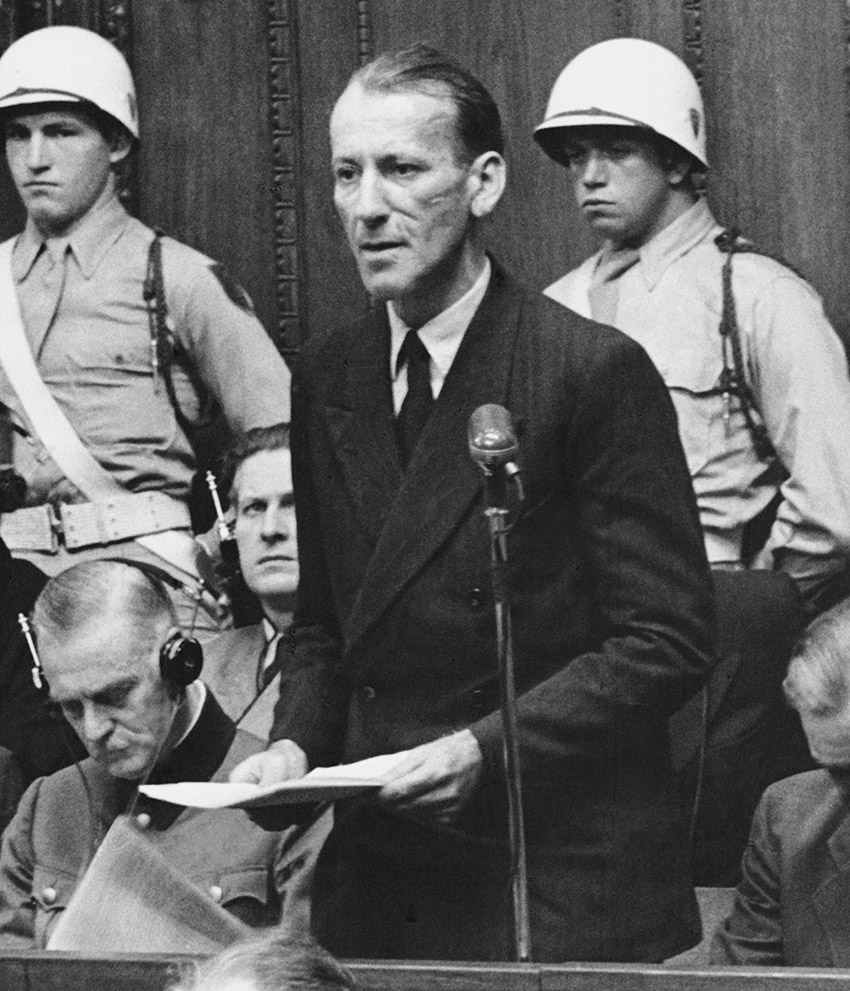

KALTENBRUNNER, ERNST (1903–1946)

Ernst Kaltenbrunner was an Austrian-born senior SS general during World War II. Between January 1943 and May 1945, he was the chief of the Reich Main Security Office (Reichssicherheitshauptamt, or RSHA) and chief of the Security Police. In the latter role, he controlled the Gestapo, Criminal Police, and Security Service (SD). He was a leading figure in the Final Solution.

Ernst Kaltenbrunner was born on October 4, 1903, in Ried, Upper Austria, the son of lawyer Hugo Kaltenbrunner and his wife Therese. His middle-class family home was influenced by the idea of a “Greater Germany,” as well as antichurch causes. Kaltenbrunner was educated at the state high school in Linz, where he became childhood friends with Adolf Eichmann. After finishing school, in 1921, he commenced studying chemistry at the Graz University of Technology. He joined the arms-carrying fraternity Arminia, and as a keen fraternity member and duelist, he became prominent in student politics. In 1923, Kaltenbrunner switched to the study of law, while at the same time working as a coal carrier. He became a spokesman for his Arminia fraternity and for nationalist students at the university and took part in anti-Marxist and anticlerical demonstrations.

Obtaining his doctorate in law from Graz University in 1926, he worked at a law firm in Salzburg for a year before opening his own law office in Linz. He became a legal consultant for the NSDAP in 1929, joining the party on October 18, 1930. He joined the SS on August 31, 1931. He became a legal consultant to the SS in 1932, at the same time as he began working at his father’s law practice. By 1933, Kaltenbrunner was head of the National Socialist Lawyers’ League in Linz. Kaltenbrunner himself was an intimidating figure. At six feet four inches tall, weighing 220 pounds, he had a powerful build, dark features, and deep scars (possibly from fencing or from a car accident) on both sides of his face.

In January 1934, Kaltenbrunner and other National Socialists were jailed by the Dollfuss government for conspiracy. While in prison, he led a hunger strike, forcing the government to release 490 Nazi Party members. In 1935, he was jailed again for high treason. This charge was dropped, but Kaltenbrunner was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment for conspiracy and lost his license to practice law.

On January 14, 1934, Kaltenbrunner married Elisabeth Eder, also from Linz and a Nazi Party member, with whom he had three children. In addition to these children, in 1945, Kaltenbrunner had twins with his long-time mistress, Gisela Gräfin von Westarp.

He was released from prison in 1935 and appointed by his leaders in Germany to command the entire Austrian division of the SS. In 1937, at the instigation of Heinrich Himmler, he was promoted to SS-Oberführer and began working with Arthur Seyss-Inquart to implement the Austrian Anschluss (union) with Germany. After the Anschluss, which took place on March 12, 1938, Kaltenbrunner became state secretary for public security and a member of the Reichstag. During 1938 and 1939, Kaltenbrunner was also involved in the organization of the Austrian Gestapo, the establishment of the concentration camp Mauthausen, and the persecution of Austria’s Jews.

Born in Austria, Ernst Kaltenbrunner was head of the Reich Security Main Office and chief of the Security Police in which he controlled the Gestapo, Criminal Police, and Security Service. During World War II he was a key figure in orchestrating and carrying out the Final Solution. In 1945 he was arrested and placed on trial at Nuremberg for war crimes and crimes against humanity; found guilty, he was sentenced to death and hanged on October 16, 1946. This image shows him testifying during the trial in 1946. (Keystone-France\Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

On January 30, 1943, in the wake of the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, Kaltenbrunner took over his principal functions as head of the RSHA, reporting directly to Himmler. At Kaltenbrunner’s instigation, anyone arrested and placed into “protective custody” (Schutzhaft) was transferred to concentration camps. Using the RSHA intelligence network, the persecution and arrest of Jews, members of resistance organizations, and other opposition groups was ongoing.

The commandant of Auschwitz, Rudolf Hoess, specifically stated that “all the mass executions in the gas chambers took place under the direct orders, the supervision and the overall responsibility of the RSHA. I received orders directly from the RSHA to proceed with these mass executions.” This placed responsibility directly at Kaltenbrunner’s feet.

Heydrich had made the RSHA more politically powerful than the Wehrmacht, and Kaltenbrunner derived the benefit from Heydrich’s assassination. In February 1944, he contrived to have Admiral William Canaris’s Abwehr (German military intelligence) completely abolished and its remnants transformed into the RSHA’s Military Branch, to be directed by Walter Schellenberg. With the unseating of Canaris, Kaltenbrunner established an intelligence service monopoly.

Kaltenbrunner’s power increased markedly after the attempted assassination of Adolf Hitler on July 20, 1944, and he was responsible for actively seeking out and calling for the execution of all those accused of plotting against the Führer. In December 1944, Kaltenbrunner, along with other SS generals, was granted the rank of general of the Waffen-SS so that if they were captured by the Allies, they could be considered as military officers rather than police officials.

On April 18, 1945, Himmler named Kaltenbrunner commander in chief of German forces remaining in Southern Europe. Kaltenbrunner organized his intelligence agencies as a stay-behind underground net, but in late April 1945, he shifted his headquarters from Berlin to Altaussee, where he had often vacationed. While there, he thwarted the efforts of local governor August Eigruber to destroy the irreplaceable collection of more than 6,500 paintings and statues stolen by the Nazis from museums and private owners across occupied Europe, with the intention of placing them in Hitler’s planned Führermuseum in Linz. Eigruber was determined to prevent the collection from falling into the hands of “Bolsheviks and Jews” by destroying it with explosives. Kaltenbrunner countermanded the order and had the explosives removed, saving world treasures such as Michelangelo’s Madonna of Bruges, stolen from the Church of Our Lady in Bruges; Jan van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece, stolen from St. Bavo Cathedral in Ghent; and Vermeer’s The Astronomer and The Art of Painting.

With the end of the war looming in 1945, Kaltenbrunner moved his headquarters again, giving orders that all prisoners were to be killed. He was arrested by the Americans in the Austrian mountains after attempting to pass as a doctor. In November 1945 at the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg, Kaltenbrunner was charged with conspiracy to commit crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. He rejected all responsibility for the charges against him and stressed during cross-examination that all decrees and legal documents that bore his signature were “rubber-stamped” and filed by his subordinates.

Kaltenbrunner’s close control over the RSHA meant that he was deemed to have direct knowledge of and command responsibility for mass murders by the Einsatzgruppen, deporting citizens of occupied countries for forced labor, establishing concentration camps and committing racial and political undesirables to them for slave labor and mass murder, screening of prisoner-of-war camps and executing racial and political undesirables, seizure and destruction of public and private property, persecution of Jews and Roma, and persecution of churches.

Kaltenbrunner claimed he was an intelligence leader, not a mass murderer. The tribunal concluded, instead, that he was an active authority and participant in many instances of war crimes and crimes against humanity. He was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity, sentenced to death, and hanged in Nuremberg on October 16, 1946.

Fritz Katzmann was a Holocaust perpetrator responsible for mass murder in the cities of Katowice, Radom, Lvov (Lviv, Lemberg), Danzig (Gdansk), and other parts of Nazi-occupied Poland. On June 30, 1943, Katzmann submitted to Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger a top-secret report, known as the Katzmann Report, summarizing Aktion Reinhard in Galicia up to that point of the year. The report was used as evidence at the Nuremberg Trials after World War II.

Friedrich (“Fritz”) Katzmann was born on May 6, 1906, in Langendreer, Westphalia, into a coal miner’s family. After elementary school, he became a carpenter but lost his job and was unemployed from 1928 to 1933. In December 1927, he joined the SA; in September 1928, the NSDAP; and in July 1930, the SS. On April 20, 1933, he was promoted to SS-Sturmbannführer.

From the beginning of April 1933 until early April 1934, Katzmann served in a municipal role in Duisburg. On January 30, 1934, he was promoted to SS-Obersturmbannführer, after which he served full-time in the SS. On August 17, 1934, he was appointed an SS-Standartenführer, having taken part in the Night of the Long Knives on June 30, 1934. From April 4, 1934, until March 21, 1938, Katzmann was stationed in Berlin.

Between mid-August 1936 and mid-August 1942, Katzmann was a member of the People’s Court (Volksgerichtshof). On March 21, 1938, he commanded an SS unit in Breslau; later in the year, on November 9, 1938 (the day of Kristallnacht), he was promoted to SS-Oberführer.

From November 1939 to July 1941, Katzmann was higher SS and police leader (Höherer SS- und Polizeiführer, or HSSPF) in Radom, Poland, in charge of the ghettoization process of Radom’s 32,000 Jews. Under his command, they were subjected to theft, terror, and murder.

On June 21, 1941, immediately in advance of the invasion of the Soviet Union, Katzmann was promoted to SS-Brigadeführer. Thereafter, until April 20, 1943, he was HSSPF for Galicia, based in Lvov. On September 26, 1941, he was further promoted to SS police major general.

In November 1941, Katzmann ordered 80,000 Jews confined to the Lvov ghetto. In the city outskirts, he also established the Janowska concentration camp. The number of those killed at Janowska has been a matter of dispute, ranging from the unlikely Soviet figure of up to 500,000 to a more realistic number of victims estimated at 35,000 to 40,000. It has been further approximated that up to 60,000 Jews were murdered overall on Katzmann’s command by the end of 1941. In 1942, Katzmann organized further transports that took at least 80,000 Jews from Lvov to the death camp of Bełżec.

Katzmann was promoted SS-Gruppenführer and lieutenant general of police on January 30, 1943. During the first half of 1943, he organized the death of over 140,000 Jews in the district of Galicia.

On June 30, 1943, just over two years after arriving in Lvov, Katzmann submitted his report entitled “Solution of the Jewish Question in the District of Galicia,” to the HSSPF of the General Government, Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger. Katzmann described in detail his actions and the Jewish resistance that resulted from them. One of the report’s conclusions was that by June 27, 1943, a total of 434,329 Jews had been expelled and that the district of Galicia was now free of Jews (Judenrein), except for those who were under Krüger’s direct control.

With Galicia Judenrein, Katzmann’s job was seen to be completed, and he was thus transferred elsewhere. From April 20, 1943, to May 8, 1945, he was SS commander of Military District XX (Vistula/Danzig/West Prussia), headquartered in Danzig. He oversaw the organization of gas chambers and crematoria at Stutthof concentration camp, where tens of thousands more Jews were murdered. On July 1, 1944, he was promoted to SS-Obergruppenführer in the Waffen-SS.

Katzmann experienced the end of the war on the island of Fehmarn, off the coast of Schleswig. He escaped immediate prosecution, living under a false identity in Württemberg as Bruno Albrecht. In March 1956, Bruno Albrecht was registered in Darmstadt, where his family lived, but a planned transfer to Argentina did not materialize, owing to Katzmann’s ill health at that time. He died on September 19, 1957, in the Alice Hospital in Darmstadt.

Bruno Kittel was an SS officer involved with Jewish issues in France, Latvia, and Lithuania during World War II. He was notorious for having been responsible for administering the liquidation of the Vilna ghetto in September 1943, having already overseen the massacre of Jews in two small communities nearby, Kena and Bezdonys, on July 8 to 9, 1943. It has been estimated that some 240 Jews were killed in Kena, and 300 to 350 were killed in Bezdonys.

Born in Austria in 1922, Kittel trained as an actor in Berlin and Frankfurt. Prior to the outbreak of war, he was known as an actor, singer, and musician (his preferred instruments were saxophone and piano). He joined the SS, reached the rank of SS-Oberscharführer, and was sent to France and Riga to learn how to manage Jewish matters.

Deployed to Vilna in June 1943, where he played his saxophone on local radio, Kittel was the youngest of his colleagues there, and his reputation as a passionate and cruel antisemite preceded him. Zealous in hunting down Jews, his reputation extended throughout occupied Poland. At the end of June 1943, for example, he ordered 418 Jewish forced laborers murdered in retaliation for the flight of 6 Jews to the partisans.

A city of 200,000 people, 30 percent of whom were Jewish, Vilna was known as the “Jerusalem of the North,” with 106 synagogues, despite a 60 percent Catholic presence. Approximately 265,000 Jews lived in Lithuania at the time of German occupation in 1941; by the end of World War II, 95 percent of them had been exterminated. No other Jewish population was so devastated in the Nazi-occupied areas of Eastern Europe.

A ghetto was established at Vilna by the Nazi military administration in September 1941. Owing to Nazi depredations, by the beginning of 1942, its population had been reduced to just 15,000, and in June 1943, Heinrich Himmler ordered the ghetto’s final liquidation. The SS chief and commander of Einsatzkommando 3 in Vilna, Rolf Neugebauer (who was later transferred to Kovno/Kaunas, and, deeper into the war, Budapest), ordered Kittel to oversee the destruction of the ghetto, which he undertook on September 22 to 23, 1943. Most of the inhabitants were taken to the nearby Ponary Forest and were shot or sent to extermination camps in Poland or to work camps in Estonia, where almost all of them died. Of those remaining, most were women and children transported to extermination camps such as Auschwitz. About 2,000 men were sent to the Klooga concentration camp in Estonia, and up to 1,700 of the younger women were sent to the Kaiserwald concentration camp in Latvia.

Constantly smiling, Kittel was remembered as elegant, polite, and refined. He was young, and his manner was intended to be calming. When executing victims, it was said that he pleaded with them not to be nervous so that he could perform his murders calmly, quietly, and deliberately.

Following the liquidation of the Vilna ghetto, Kittel continued his deadly procession. On October 15, 1943, he visited the Kailis forced-labor camp near Vilna, which had received a number of Jewish prisoners from the ghetto. Selecting 30 inmates at random, he had them dispatched to the killing fields at Ponary on a whim. The camp itself was liquidated, and its remaining workers were executed at Ponary, on July 3, 1944, although this was long after Kittel had left the vicinity.

Kittel’s remaining activities during the war are sketchy. It is known that on March 27, 1944, he was present in Kovno, where he was involved in what became known as the Kinderaktion, when the Germans came for the ghetto’s remaining 1,700 children. Under Kittel’s watching eye, the ghetto’s 130 Jewish police were then taken at gunpoint to a nearby SS base known as the Ninth Fort, where they were tortured for information regarding the hiding places of other Jewish children as well as partisans. Kittel selected upward of 40 of these men and arranged for their summary execution.

With the advance of the Russians, Kittel took leave of all his SS activities and disappeared without trace. His trail ran cold, and he was thus never held responsible or prosecuted for his crimes during the war.

KLIMAITIS, ALGIRDAS (1923–1988)

Algirdas Klimaitis was a Lithuanian collaborator with the Nazis during World War II. The militia he commanded was notorious for its role in the Kovno (Kaunas) pogrom in June 1941 and was active during Operation Barbarossa.

Algirdas Jonas Klimaitis was born in 1923 in Lithuania. For some time, he traded in livestock but went bankrupt. Later, he began writing for newspapers and worked as a far-right-wing journalist. Prior to World War II, he edited the tabloid newspaper Dešimt centų (Ten Cents) and was a member of the Voldemarininkai, a right-wing nationalistic movement following Augustine Voldemar, who had negotiated for independence for Lithuania at Versailles. Klimaitis was a supporter of anticommunist and antisemitic ideals.

On Sunday, June 22, 1940, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union. The next day, the Lithuanian Activist Front (Lietuvos Aktyvistų Frontas, or LAF) seized the radio station and announced the establishment of a provisional Lithuanian government. Two days later, on Wednesday, June 25, the German army entered Kovno, the country’s second-largest city. Lithuanians rejoiced because they were rid of the Soviet presence that had been occupying their country, but the German military was indignant that the Lithuanians had given themselves the status of an independent country. General Wilhelm Schubert met with Lithuanian leaders and announced that any possibility of an independent Lithuania would never be achieved.

SS-Brigadeführer Franz Walter Stahlecker was commandant of Einsatzgruppe A, tasked to pacify occupied Lithuania. As the head of the SiPo and SD, Stahlecker sought local movements that would “self-cleanse” their communities of Jews and achieve this as rapidly as possible. It was important to establish as “unshakable and provable facts” that the liberated population took such measures against the Bolshevik and Jewish enemy on its own initiative without any German instructions.

From the Germans’ viewpoint, this was necessary in Lithuania, for, in some places such as Kovno, Jews had armed themselves and taken an active part in sniping and arson. In addition, the Jews of Lithuania had cooperated closely with the Soviets.

Stahlecker sought dependable people who would provide cover for the SD’s action. He identified a local Lithuanian military representative named Simkus and an army faction calling itself the Iron Wolf. Stahlecker spoke with Jonai Dainauskas, head of the Interim Lithuanian Security Police, to prepare pogroms, but Dainauskas refused. Stahlecker reported to SS-Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler that “It suddenly turned out that organizing a larger-scale Jewish pogrom is not quite easy.” Instead, Stahlecker used two groups of partisans who had fought in Kovno against the Soviets. The first group was 600 men, mainly civilian workers under the leadership of Algirdas Klimaitis; the second was about 200 men following a physician, Dr. Zygonys. Stahlecker authorized Klimaitis and Zygonys to recruit an auxiliary police force.

On the night of June 25 to 26, Stahlecker instigated a pogrom led by Klimaitis’s unit, making it appear that this was a spontaneous Lithuanian affair not initiated by the Germans. The Lithuanian auxiliaries set fire to synagogues and about 60 homes in the old Jewish quarter and began shooting Jews in the streets. On the first night, some 1,500 Jews were killed. On the second night, 2,300 more Jews were murdered. The chance for plunder provided a powerful motive; after the owners were killed, the auxiliaries looted homes and warehouses and ripped valuables from bodies. In addition to these 3,800 people, a further 1,200 people were killed in surrounding towns and villages by June 28.

In Kovno, film and photographs were used to establish, as far as possible, that these first “spontaneous” measures against Jews and communists were carried out by Lithuanians. Between June 24 and July 2, two Einsatzkommandos (9 and 7) arrived in Vilnius and organized snatch squads, which kidnapped Jews and either held them in Lukiskiai Prison or took them into the Ponary Forest and shot them.

Klimaitis was not operating under the authority of the Lithuanian Provisional Government. The acting prime minister of Lithuania, Juozas Brazaitis-Ambrazevičius, claimed in his memoirs that the Provisional Lithuanian Government sent Generals Stasys Pundzevičius and Mikė Rėkaitis to instruct Klimaitis not to create pogroms and not to serve under Stahlecker. When Klimaitis met the two generals, he attempted to justify the pogroms, and in response, the generals informed him that his behavior was blackening Lithuania’s name and that Klimaitis was doing the Nazis’ dirty work for them. Klimaitis justified his actions on the basis that Stahlecker was threatening to eliminate him if he did not follow orders. The generals advised Klimaitis to disappear, which he soon did.

Lithuanians who continued with pogroms against the Jews were commanded by the leader of the LAF, Aleksandras Bendinskas. Klimaitis did not participate in these later massacres.

On Saturday, June 28, 1940, the few remaining Lithuanian rebel groups operating in Kovno were disarmed and disbanded. Those deemed “reliable” were then selected and formed into five police companies. The next day, the Kaunas Military Command established the National Defense Forces Battalion. The Lithuanian Interim Government hoped it would be the beginning of the Lithuanian army, but instead the battalion began murdering Jews. Overall, across the duration of the Nazi occupation, the total number of Jews liquidated in Lithuania was 71,105.

After the war, Algirdas Klimaitis settled in Hamburg, Germany, where he lived quietly until discovered in the 1970s. The Hamburg Public Prosecutor’s Office filed a lawsuit against him, but he died on August 28, 1988, without facing trial.

Gerhard Klopfer was a lawyer, senior official of the Nazi Party, and assistant to Martin Bormann in the Party Chancellery. One of the most influential and knowledgeable bureaucrats of the Nazi regime, he participated in the Wannsee Conference in January 1942, which discussed how to murder Jews in the most efficient and effective manner.

Gerhard Klopfer was born in the East Prussian town of Schreibersdorf on February 18, 1905, the son of a farmer who was also a provincial official. He attended the local high school prior to studying at the universities of Breslau and Jena, where his academic focus was on law and political science. He also served as a temporary volunteer in the Ulm Artillery Regiment in December 1923. His doctoral thesis from the University of Jena in 1927 was in employment relations, which led to his appointment as a judge. Through his university life, he met Wilhelm Stuckart, who later became secretary of state at the Reich Ministry of the Interior.

Klopfer joined the Nazi Party on April 10, 1933, and the SA on April 15, 1933. On November 1, 1933, he was appointed as a state prosecutor in Düsseldorf. Positions were available because the new Nazi regime had dismissed many civil servants, especially Jews. Klopfer was promoted in quick time, and on December 1, 1933, he was transferred to the Prussian State Ministry for Agriculture, Lands, and Forests.

On August 1, 1934, Klopfer was promoted to government counselor, and on December 8, he took up a role in the Gestapo. A loyal and reliable party member, on April 18, 1935, he became a staff member of the Representatives of the Führer, headed by Rudolf Hess and Martin Bormann, Hess’s former deputy. Klopfer joined the SS on September 15, 1935, and remained a member until May 1945. In 1938, Klopfer personally took part in implementing the regulations of the Nuremberg Laws and was responsible for seizing Jewish businesses. When Hess flew to England on an unauthorized mission in 1941, Klopfer became Bormann’s assistant and head of the state division of the Party Chancellery. In this role, he deputized for Bormann at the Wannsee Conference on January 20, 1942.

Klopfer was one of the most notable and knowledgeable bureaucrats of the Nazi regime. As head of Constitutional Law Section III of the chancellery and Martin Bormann’s deputy, he managed issues relating to “race and national character,” economic policies, cooperation with the Reich Security Main Office, and the basic politics of occupation. In November 1942, as state secretary, he restricted the rights of Jews living in mixed marriages.

Klopfer therefore had extensive power of patronage within the Nazi Party, and Bormann often left him to handle appointments to party positions. As Bormann’s deputy, he was a signatory to the call to arms of Germany’s youth and elderly, in the age range of 16 to 60 years (the so-called Volkssturm) in the final stage of the war. In 1944, he was promoted to SS-Gruppenführer.

As the Red Army closed in on Berlin in 1945, Klopfer fled from Berlin and went into hiding. It was not until March 1, 1946, that he was arrested by agents of the Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) in Munich with false papers in the name of Otto Kunz. He was sent first to the Dachau Detention Center before being transferred to the Ludwigsburg and Nuremberg-Langwasser camps.

Klopfer was interrogated some 10 times by American prosecutors between March 1947 and January 1948, during which he sought to minimize his importance and maximize his ignorance. He was a witness during the Wilhelmstrasse trials of many of the former Nazi state secretaries at Nuremberg in 1948. Under questioning, Klopfer denied having anything to do with the destruction of the Jews, admitting only to hearing rumors about it. He stated that in 1935 he had been commanded against his will to organize the party and that his professional abilities had been the reason for his rapid promotion; all political responsibility was with his superior, Martin Bormann. When confronted with the minutes of the Wannsee Conference, Klopfer did not recall the wording as set out in the protocol and said that he had always assumed that the Jews were only to be “resettled.”

Although he was marked for prosecution in a new U.S. military tribunal case, the plan to place him on trial was canceled on the grounds of insufficient evidence. The United States was facing new priorities owing to the Cold War, and Western unity became more important than the pursuit of criminal justice. Evidence prepared against Klopfer by U.S. authorities was handed over, along with additional documentation, to a German investigative commission. The implementing legislation of the Basic Law 131 allowed thousands of former Nazi officials to return to the state service, and the impunity laws adopted by the Bundestag in 1949 and 1954 reversed essential measures of the Allied denazification process.

Klopfer settled in Ulm, resuming his law practice there in 1956. The District Attorney’s Office in Ulm, responding to pressure from the Central Office for the Prosecution of Nazi Crimes in Ludwigsburg, initiated inquiries into Klopfer’s role in the Final Solution, but proceedings against him were dropped once and for all on January 29, 1962.

Klopfer was to live longer than any other participant in the Wannsee Conference, dying on January 28, 1987, at a home for the elderly outside the Baden-Württemberg city of Heilbronn.

Ilse Koch was the wife of the commandant of the Nazi concentration camps at Buchenwald and Majdanek. In 1947, she became one of the first prominent Nazis to be tried twice by two different regimes for her behavior during the Third Reich: first by the U.S. military and then by the German government.

Margarete Ilse Köhler was born on September 22, 1906, in Dresden, the daughter of a factory foreman. At 15 years old, she studied accountancy, later working as a bookkeeping clerk. In 1932, she joined the Nazi Party. In 1934, she met Karl Otto Koch in 1934 through friends in the SA and SS and got engaged. She started work in 1936 as a guard and secretary at Sachsenhausen concentration camp near Berlin, which Karl Koch commanded. They were married later in 1936, and she changed her name to Ilse Koch. In 1937, her husband was made commandant of Buchenwald, and she went there with him.

At Buchenwald, it is claimed that Ilse Koch assisted a prison doctor to complete his thesis on criminality and tattooing by ordering selected prisoners to be murdered and skinned so as to retrieve the tattooed parts of their bodies. It was here that she acquired her reputation as a sadist, beating prisoners with her riding crop and forcing them to perform physically exhausting activities for her own amusement. Ilse Koch’s abuses were evidenced at trial. She was a rabid antisemite, called Jews “swine,” and had derision for anyone not fitting the Nazi ideal. She would order her dog to attack on command anyone she viewed as a threat to her person. If laundry was not done to her liking or if anyone spoke out of turn, the miscreant would be executed.

Evidence was given at trial that her hobby was collecting lampshades, book covers, and gloves made from the skin of specially murdered concentration camp inmates, as well as shrunken human skulls. An anecdote tells of a 19-year-old American soldier who, after the war, found several lampshades with beautifully painted butterflies and birds; then, he and his three buddies went out and vomited when they identified that the lampshades were made of human skin.

In 1940, Ilse Koch constructed an indoor sports arena costing over 250,000 Reichsmarks, most of which had been seized from the inmates. Her husband, suspected of enriching himself by skimming profits from the camp that should have gone to the SS, was relieved of command at the end of 1941. He was transferred to Lublin to establish the Majdanek concentration and extermination camp, but Ilse Koch remained at Buchenwald.

On August 24, 1943, Ilse and Karl Koch were arrested on the orders of the SS and police leader for Weimar, who was responsible for supervising Buchenwald. They were charged with making themselves privately wealthy by theft and embezzlement and with murdering prisoners to prevent them testifying. Ilse Koch was jailed until 1944, when she was cleared for lack of evidence; her husband was found guilty, sentenced to death in Munich by an SS court, and executed by firing squad at Buchenwald on April 5, 1945.

Ilse Koch went to live with her surviving family in the town of Ludwigsburg, where she was arrested by U.S. authorities on June 30, 1945, after having been identified by a former Buchenwald inmate as the fierce redheaded woman who was perverse and brutally cruel. The prisoners called her the “Witch of Buchenwald,” which the press transformed into the “Bitch of Buchenwald.”

In 1947, Koch was charged with aiding, abetting, and participating in the murders at Buchenwald. Among the physical evidence against her was a lampshade made of human tattooed skin, which outraged international public opinion. The trial began on April 11, 1947, and on August 19, 1947, she was sentenced to life imprisonment for “violation of the laws and customs of war.” On June 8, 1948, after two years of her sentence, the interim military governor of the American Zone in Germany reduced her life sentence to four years imprisonment on the basis that “there was no convincing evidence that she had selected inmates for extermination . . . to secure tattooed skins, or that she possessed any articles made of human skin.”

The Bavarian government gave notice that if Koch was released, new proceedings would be brought against her. She was freed in October 1949, and after bureaucratic wrangling between the U.S. government and the government of East Germany, she was handed over to West German authorities, who arrested her.

Public opinion was irate. In 1949, she was put on trial a second time, now before a West German court. On November 27, 1950, the trial commenced before the District Court at Augsburg. It lasted seven weeks, during which 250 witnesses were heard, including 50 for the defense. The 16 prosecution witnesses gave evidence that she had brutally abused prisoners in the camp, using the power that her husband had arbitrarily granted her to perpetrate sadistic and perverse acts on Buchenwald’s inmates. The heart of the trial became the famous articles made of human skin.

At least four separate witnesses for the prosecution testified that they had seen Koch choose tattooed prisoners who were then killed or that Koch had seen or been involved in the process of making human-skin lampshades from tattooed skin. However, this charge was dropped by the prosecution when they could not prove that the lampshades or any other items were made from human skin.

On January 15, 1951, the court gave its verdict. It ruled that the previous trials in 1944 and 1947 were not a bar to proceedings (being tried twice for the same offence), as at the 1944 trial, Koch had only been charged with receiving, whereas in 1947 she had been accused of crimes against foreigners after September 1, 1939, and not with crimes against humanity, for which Germans and Austrians had been defendants both before and after that date. On January 15, 1951, she was sentenced to life imprisonment and permanent forfeiture of civil rights.

On September 1, 1967, Ilse Koch, then 60, hanged herself in her cell at Aichach women’s prison.

Wilhelm Koppe was a Waffen-SS general responsible for mass crimes against Poles and Jews in the General Government and elsewhere during the German occupation of Poland in World War II.

Karl Heinrich Wilhelm Koppe was born on June 15, 1896, in Hildesheim, Lower Saxony, to Robert Koppe, a bailiff, and his wife. He attended a private school in Stolzenau and the Realgymnasium Harburg-Wilhelmsburg, completing his high school education in 1914. In October 1914, he volunteered to serve in the Schleswig-Holstein Pioneer Battalion No. 9 and served on the Western Front in January 1915. In December 1916, he became a lieutenant of the reserve, and from January 1917 until December 1918, he served as battalion gas officer of the Pioneer Battalion No. 9. Wounded in Flanders, he was discharged at the end of the war.

In the interwar period, he was an independent merchant and owner of a wholesale business in food and tobacco products. Koppe joined the Nazi Party on January 9, 1930, serving from December 1930 to January 1932 as the press officer of the party’s Harburg-Wilhelmsburg branch. He joined the SA in 1931 and the SS in 1932. Prior to World War II, he was a regional SS and SD commander, first in Münster and then in Danzig, Dresden, and Leipzig. From 1933 to 1945, he was an NSDAP member of the German Reichstag.

In October 1939, after the German invasion of Poland, Koppe became the SS and police leader in Reichsgau Wartheland, based in Posen (Poznań), under the command of Arthur Greiser. Koppe actively implemented Nazi racial ideals in his region, declaring in November 1939 that he would make Posen “free from Jews.” He thereupon ordered many executions and deportations of Poles and Polish Jews. Later, Koppe took charge of the deportation of the Jews to the Łódź ghetto and the Chełmno extermination camp.

On November 12, 1939, Koppe announced to the Generalgouvernement the long-term goals of the deportations. These were to transform the conquered Polish territories into German settlements. To this end, so-called Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans living outside of Germany proper) were to be resettled. He stated further that all Jews and Polish intellectuals were equivalent to dangerous criminals, so the cleansing and safeguarding of the area could only be achieved when all had been removed. That was also necessary to create jobs for Germans moving to the newly conquered territory.

Koppe also was active in the Nazi euthanasia program as the overall commander of Sonderkommando Lange. Toward the end of May 1940 and until June 1940, Koppe organized the mass murder, using gas vans, of some 1,558 Germans and around 500 Poles with disabilities in the East Prussian transit camp Soldau.

On January 1, 1942, on the orders of SS-Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler, with whom he had established a good working relationship, Koppe was promoted to SS general and placed in charge of the police. On September 11, 1943, he took over in Kraków from Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger as state secretary and general procurator for the armament of the governor-general for the occupied Polish territories, reporting to Hans Frank. In this new role, he participated in the activities at Chełmno and in operations against the Polish resistance. Koppe organized the execution of more than 30,000 Polish patients suffering from tuberculosis and ordered that all men identified as resistance fighters should be executed and the rest of their families sent to concentration camps.

On July 1, 1944, Koppe was appointed as general of the Waffen-SS and the police. On July 7, 1944, he was the target of an unsuccessful assassination attempt by the Polish resistance; he survived, but five members of the resistance were killed.

As the Eastern Front approached Poland, Koppe ordered that all prisoners under his command be executed rather than rescued by the Soviets. In 1945, he was appointed as commander of the special staff of the Army Group Vistula, and from April 4, 1945, to May 8, 1945, he held the positions of senior SS and police leader in Munich.

In April 1945, shortly before Germany’s collapse, Koppe issued himself personal-identity cards with changed name, date of birth, and birthplace. Under the alias of Lohmann, his wife’s surname, he then went into hiding. He worked as a director of the Sarotti chocolate factory in Bonn, Germany, managing to remain undetected until 1960.

On December 30, 1960, due to an anonymous street advertisement in Bonn, Koppe was arrested and held in custody until he was released on bail of 30,000 deutsche marks on April 19, 1962. Meanwhile, in 1961, criminal proceedings were initiated against him by the Landgericht Bonn, for the mass murder of 145,000 people during the first phase of the Chełmno exterminations. Adolf Eichmann, on trial in Israel during 1961, did not help Koppe’s position when he made statements against Koppe that further incriminated him. These, in turn, were sent to the prosecutor’s office in Bonn.

Koppe’s trial opened on October 9, 1964. It was postponed due to an illness which held up the proceedings, and on August 25, 1966, the Bonn court decided not to prosecute; instead, it released him on the grounds of “mental decay.” The German government then rejected a Polish request for extradition. Koppe died on July 2, 1975, in Bad Godesberg, near Bonn, where he is buried.

Josef Kramer was a German SS officer who served as the commandant of Auschwitz-Birkenau and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps. Called the “Beast of Belsen” by camp prisoners, he was directly responsible for the death of tens of thousands of Jews.

Kramer was born in Munich on November 10, 1906, an only child in a strict Roman Catholic family. In 1915, the family moved to Augsburg, and Kramer initially worked as a bookkeeper. After losing his job, he was mostly unemployed from 1925 until 1933.

In December 1931, he joined the NSDAP, followed by the SS a month later. In 1934, he became a concentration camp guard, initially working at Dachau before moving on to Sachsenhausen and later to Mauthausen. On October 16, 1937, he married Rosina, a schoolteacher, with whom he had three children.

In 1940, Kramer was assigned to assist Rudolf Hoess, the newly installed commandant at Auschwitz. He accompanied Hoess to inspect the Auschwitz location as a possible site for a new plant for synthetic coal oil and rubber, a vital industry given Germany’s shortage of oil. SS-Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler was impressed by Kramer’s attention to strict discipline.

Kramer served from May 1941 to August 1943 as commandant of the Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp in Alsace-Lorraine, France. Here, he personally carried out the gassing of 80 Jewish men and women, part of a group of 87 selected at Auschwitz to become anatomical specimens in a proposed Jewish skeleton collection to be housed at the Anatomy Institute at the Reich University of Strasbourg under the direction of August Hirt, an anatomist at the Strasburg Medical University.

Josef Kramer served as the commandant of Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp between May and November 1944, and Bergen-Belsen from December 1944 until the camp’s liberation on April 15, 1945. Responsible for the death of thousands of people, he was known by camp inmates as the “Beast of Belsen.” While there he instituted a regime of strict discipline and sadism, and lengthy roll calls, harsh labor, and insufficient food became common features of camp life. At the end of the war he was detained by the British army, convicted of war crimes, and hanged. (George Rodger/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

At the beginning of May 1944, Kramer returned to Auschwitz with Hoess to assist in the mass murder of Hungarian Jewry. Between May 15 and July 9, 1944, approximately 430,000 Hungarian Jews were deported, for the most part to Auschwitz. Kramer was the commandant of the killing center at Auschwitz, known as Auschwitz II, between May and November 1944. After the war, several witnesses declared that they had seen Kramer regularly during the selections of people to be murdered in the gas chambers that took place immediately after the arrival of a transport.

In December 1944, Kramer was appointed as commandant of the camp at Bergen-Belsen. He brought to Belsen the strict discipline and sadism he had already demonstrated, and lengthy roll calls, harsh labor, and insufficient food became common features of camp life.

As Nazi Germany began to disintegrate in early 1945, more and more transports brought prisoners to the already overcrowded Belsen. Vast numbers began to die each day from typhus, and Kramer undertook virtually nothing to improve living conditions. The large stocks of medicines and medical instruments he had at his disposal were not made available to the prisoners, among whom were several doctors.

With a population of 15,257 inmates at the end of 1944, the number soared to 44,000 by March 1945. By April, order in the camp had vanished, while Allied bombings had disrupted water and food supplies. As the typhus epidemic raged, the camp’s crematorium could no longer handle the increasing number of bodies. Corpses were simply left to rot, and with Allied armies penetrating Germany, prisoners from camps at risk of being overrun were transported to Belsen. During the week of April 13, 1945, more than 20,000 additional prisoners were transported to the camp, and numbers increased even more.

On April 15, 1945, British troops liberated Belsen. They found some 40,000 starving survivors along with around 35,000 unburied corpses scattered throughout the camp. To his own surprise, Kramer was arrested.

Josef Kramer was imprisoned at the Hameln jail, and on September 17, 1945, he was tried along with 44 other camp staff by a British military court at Lüneburg. The prosecution detailed the horrific conditions of Bergen-Belsen and presented evidence of Kramer’s time spent at Auschwitz. Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, a cellist and surviving member of the Auschwitz Women’s Orchestra, testified that Kramer took part in selections for the gas chamber. His defense argued that he was merely following orders in a time of war and had been following German laws, but this defense was not accepted by the court.

Kramer wrote during his defense that he was a fanatical Nazi and did only what he thought was right. He wrote that he was thankful that he and his family were not born Jews, since that would mean they would have had to die. He wrote that he did not see the inmates as people and never did what was forbidden by SS rules.

Josef Kramer was found guilty on November 17, 1945. He was hanged on December 13, 1945, aged 39, in Hameln.

KRÜGER, FRIEDRICH-WILHELM (1894–1945)

Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger, a senior member of the SA and the SS, was notorious for his actions in Poland during World War II. From 1939 and 1943, he was the higher SS and police leader in the General Government in German-occupied Poland. In that role, he was responsible for crimes against humanity, including the establishment of concentration camps, forced labor, and mass murder. At the same time, he had a major responsibility for the Holocaust in Poland. His brother, Walter Rudolph Krüger, was also a Waffen-SS general.

Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger was born on May 8, 1894, into a military family in Strassburg (Strasbourg), Elsass (Alsace), Germany, the son of Colonel Albert Krüger. His father was killed on August 6, 1914, while serving as a regimental commander in World War I. Krüger discontinued high school to undertake training as a cadet in military academies in Karlsruhe and Gross-Lichterfelde. On March 22, 1914, he joined the Prussian army as a lieutenant in an infantry regiment. He served this regiment as a platoon and company commander, was wounded in combat three times, and earned the Iron Cross First and Second Class.

After the war in 1919, Krüger became a staff officer with the 20th Infantry Division, leaving the army in May 1920 as a first lieutenant. At the same time, from August 1919 to March 1920, he served in the Freikorps von Lützow. He returned to civilian employment, working in the book trade until 1923. He married Elisabeth on September 16, 1922, and had five children: two from his wife and three foster children. From 1924 to 1928, he served as a director of a refuse company, after which he set up his own business as an independent merchant.

Krüger became a member of the NSDAP in November 1929 and joined the SS in August 1930. He was commissioned as an SS-Sturmführer on March 16, 1931. In April 1931, he became a member of the SA. Due to the influence of his friend Kurt Daluege, in 1932, Krüger was elected as SA group leader in the personal staff of the SA chief Ernst Röhm.

In 1933, he was elected to the Reichstag, serving as a member until the end of the war in 1945. He took charge of SA training and was promoted in June 1933 to SA-Obergruppenführer. After the Röhm Putsch of June to July 1934 (which he avoided), Krüger moved back to the SS.

From March 1936 to October 1939, Krüger ran the SS border units, and between May 1938 and October 1939, he was also inspector of Allgemeine-SS mounted units. With the outbreak of war, he was promoted to the position of higher SS and police leader Ost for the General Government based in Kraków, one of the highest posts in occupied Poland. In this position, he was responsible for, among other things, the running of counterinsurgency operations in the concentration camps, the establishment of forced-labor camps, the use of police and SS in the deportation of Jews from the Warsaw ghetto, the carrying out of Operation Harvest Festival (Aktion Erntefest), the fight against resisters in the General Government, and the ethnic cleansing of hundreds of thousands of Polish farmers from the area around Zamość. Krüger became a police general on August 8, 194, and commanded Oberabschnitt “Ost” (Senior District East) from mid-September 1939 to October 1943, as well as being deputy governor (Reichskommisar) for the General Government from April 1942 until his departure from Poland.

Krüger’s actions throughout this time caused massive suffering for both Jews and Poles, as he was deeply implicated in carrying out Nazi racial policies. SS-Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler gave Krüger responsibility to complete the destruction of Polish Jewry. During the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising from April 19 to May 16, 1943, SS General Jürgen Stroop sent his daily reports on the suppression of the uprising and the ghetto’s subsequent liquidation directly to Krüger. Poles involved with the resistance movement ordered Krüger’s death, but on April 20, 1943, an assassination attempt in Kraków failed when two bombs missed hitting his car.

Political disagreements framed as competence disputes with Governor-General Hans Frank led to Krüger’s dismissal on November 9, 1943, and his replacement by Wilhelm Koppe. After his dismissal, Krüger requested a combat assignment, which was granted. From November 1943 until April 1944, he served as a divisional commander with the Seventh SS Volunteer Mountain Division Prinz Eugen in Nazi-occupied Yugoslavia, which fought against partisans until December 1944. While ostensibly engaged in these actions, this unit became notorious for committing atrocities against the civilian population.

On May 20, 1944, Krüger was appointed a full general of the Waffen-SS. From May to August 1944, he led the Nord Division in Northern Finland. Then from August 1944 until February 1945, he was commanding general of the Fifth SS Mountain Corps, which, along with elements of other Waffen-SS units, helped to hold a vital bridgehead in the Vardar Corridor in Macedonia that helped 350,000 German soldiers escape from possible encirclement by the advancing Soviets.

In February 1945, after the Red Army in the Vistula-Oder operation had broken through the German Eastern Front, Krüger commanded the Fifth SS-Freiwilligen-Gebirgs-Korps, subordinated to the Ninth Army of the Vistula Army Group. During April and May 1945, he was commander of a combat unit of the Ordnungspolizei (Orpo) at Army Group South.

At the end of the war, in American captivity, Krüger took his own life in Gundertshausen, Upper Austria, on May 10, 1945.