“Alice La Blonde” was the nickname given to Alice Mackert, who served as the secretary-general of the Gestapo in Nice, France, during the German occupation of the area.

She was born in Switzerland in 1916. Moving to France in 1937, she took in sewing in Alençon. She arrived in Nice in 1943 as support staff to the Gestapo following the German invasion of Vichy France after the withdrawal of the Italian occupying forces from the region. She became the mistress of Alfred Schultz, her boss and one of the local Gestapo leaders. Schultz had been a former professor of French and served in Nice as an interpreter on behalf of the German police. Allegedly, Mackert was also the mistress of Alois Brunner during the last few weeks he was in Nice.

The Hermitage Hotel, housing the Gestapo in Nice, was built in 1905 for European tourists who came south for the summer. It served as a hotel from 1905 until 1939, except during World War I, when it acted as a military hospital.

After the fall of France on June 22, 1940, Nice was in the unoccupied zone, and despite the anti-Jewish legislation introduced by the Vichy regime, it became a haven for Jewish refugees who fled to the south hoping to stay out of the Nazis’ reach. The Italian Armistice Commission partially requisitioned the hotel.

On June 2, 1941, the law required that all Jews must be registered. As early as June 25, 1941, the prefect of Alpes-Maritimes asked the mayors to provide him with “a preliminary list of all Jews or Jews deemed to be Jewish in your commune: these lists should be secretly established, in order to allow a first check on subsequent declarations.” The prefect estimated that there were 15,000 Jews in the department.

On September 8, 1943, Italy surrendered, and the Germans moved into Nice. Two days later, Alois Brunner, a top aide to Adolf Eichmann, took possession of the Hermitage Hotel, where he set up his headquarters. He immediately started organizing some of the war’s most violent raids against the Jews. Teams of SS officers routinely patrolled the city, snatching anyone off the street who “looked” Jewish. A bounty of 3,500 francs was paid to those who denounced a male Jew, and from November 1943, this was increased by “performance bonuses.” From September 10, 1943, up to the time Brunner left Nice, a total of about 80 days, no fewer than 2,142 Jews were rounded up. At the Hotel Hermitage, they were registered and then sent to the death camps via the nearby train station.

Alice La Blonde flourished in this environment, and the basements of the hotel functioned as torture rooms. She was reputed to be a sadistic and brutal torturer who used a sharp whip. Described as being “elegantly depraved” by the paper La Liberté, she was feared by all, even her leaders.

She was responsible for attempting to trap and denounce Bishop Paul Rémond. The Germans wanted to move against Rémond but were held back by their concern that Rémond was very popular; accordingly, they created a trap. Alice showed up at Rémond’s residence with two Jewish-looking children and begged Rémond to “hide them as you have hidden so many others.” The bishop had been briefed about Alice as a known Gestapo agent ever since she had entered the local boys’ vocational school looking for Jewish boys to arrest. She was reputed to be “a piece of work” and was easily recognizable by her dyed blond hair (as one observer recalled, “too blonde to be believed”). The bishop continued to repeat that he had no facilities at the residence to take in children. Alice became increasingly agitated and started to plead loudly that the children needed help, but Rémond continued to deny her help and showed her politely to the door.

At the end of the war, Alice La Blonde was arrested. On May 6, 1946, at the request of the director general for services and research, the investigating judge signed the decision to divest the Nice Court of Mackert and granted her a closed hearing. She was well defended by an excellent legal team. Despite the evidence of 32 witnesses, no testimony ultimately was considered to have proven her guilt, despite compelling evidence pointing to her antisemitism and support of the Gestapo’s actions in arresting and deporting Jews.

At dawn on June 1, 1946, Mackert left the New Prison at Nice for transport to Marseille. On December 3, 1946, the Nouvelliste Valaisan reported that the military court trial of Alice La Blonde had commenced, referring to Alice as the Nice Gestapo’s torturer. Before the military court of the ninth region, she denied being the mistress of an Abwehr officer named Baina, who had executed six members of the resistance. However, her cruelty in insisting on sending the Jewish wife and children of a non-Jewish soldier serving for France was upsetting to the judge.

On December 6, 1948, the Jewish Telegraph reported that the French woman Alice Mackert, who had aided the Gestapo and who was responsible for the death of about 5,000 Jews, had been sentenced to hard labor for life. Notwithstanding that she was suspected of double dealing and that her persona was a symbol of Gestapo horrors and collaboration, inexplicably Alice Mackert was surreptitiously spirited out to the United States after the success of her appeal on points of law. She was traced to Ohio, where she died at the advanced age of 98 in 2012.

Karin Magnussen was a German biologist, teacher, and researcher at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics during the Third Reich, propagating National Socialist racial doctrine. At the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, she was known for her studies of heterochromia iridis (different-colored eyes) using iris specimens supplied by Josef Mengele from Auschwitz concentration camp victims.

She was born on February 9, 1908, in Bremen, Germany, into the middle-class home of landscape painter and ceramist Walter Magnussen. She completed her schooling in Bremen and then studied biology, geology, chemistry, and physics at the University of Göttingen.

Magnussen joined the National Socialist German Students’ League (NSDStB) while she was still an undergraduate. By 1931, aged 23, she was a member of the NSDAP. The same year, she became a leader of the League of German Girls (BdM) and a member of the National Socialist Teachers League. As a BdM leader, she gave lectures on racial and demographic politics in Bremen. She graduated in 1932, having passed examinations in botany, zoology, and geology. In July 1932, her doctoral thesis, “Studies on the Physiology of the Butterfly Wing,” was accepted, after which she studied at the Zoological Institute of the University of Göttingen. In 1935, she commenced work in the Nazi Racial Policy Office in Hanover, and in 1936, she completed writing Race and Population Policy Tools, which was published in 1939.

In 1936, Magnussen topped state examinations for high school teaching positions, and from 1936 to 1941, she was employed in Hanover as a secondary-school teacher. In the autumn of 1941, having received a scholarship, she suspended her teaching position and transferred to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Genetics, and Eugenics (KWI-A) in Dahlem, Berlin. Her value to the KWI-A was in her party connections and her credentials as a biologist.

It was originally intended that at the KWI-A, Magnussen would assist human geneticist Hans Nachtsheim, but he refused a request from the director, Eugen Fischer, to hire her because she was “a fanatical Nazi and antisemite.” Magnussen worked instead under another famous geneticist, Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer, and remained one of his assistants even after he became director of the KWI-A in 1942, upon Fischer’s retirement. At the KWI-A, Magnussen met Dr. Josef Mengele, who worked there temporarily.

From July 1943, a research-funding organization, the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), promoted Magnussen’s study to “explore the heritage conditionality for the development of eye color as a basis for racial and ethnicity studies.” In the third published edition of Race and Population Policy Tools in 1943, Magnussen wrote that the war then in progress “is not just about the preservation of the German people, but is about which races and peoples should live in the future on European soil . . . Judaism has significant influence in all of the enemy states.” Magnussen warned of “the many dangers” that confronted Germany, ranging from Africans, Roma, and especially Jews, whom she viewed as a treacherous 1 percent of the German population.

Magnussen’s interest in eye coloring continued. First, she bred rabbits with exactly the same hereditary characteristics—that is, heterochromia—as in humans. In the summer of 1944, she used them to test “the effect of several hormones and pharmacologically active substances on the pigmentation in the eyes of various color breams,” as the DFG reported.

From a colleague, she learned that more twins and family members with heterochromic irises would be found in a Sinti community in Mechau, northern Germany. Members of various families were taken in the spring of 1943 to the KWI-A. They were photographed before being sent to Auschwitz, where Mengele had worked since late May 1943 as camp physician. A report by an inmate physician indicated that six twins and a family with eight members were selected from the Roma (“Gypsy”) camp and killed so that their eyes could be “harvested” for Magnussen’s and von Verschuer’s research.

Magnussen’s experiments on rabbits were replicated by Mengele on Sinti human subjects. An eyewitness at Auschwitz reported that several SS doctors carried out experiments on newborn babies to change the color of their eyes.

At the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, Magnussen examined the eyes of murdered prisoners sent to her by Mengele. She received sufficient number of eyes for her research to assure that the research agenda of the KWI-A would be supported. Magnussen used the scientific method to conclude that eye color is not only genetically but also hormonally determined.

Mengele pledged to Magnussen to give her an uninterrupted supply of victims’ eyes for further research and evaluation, and as a result, the second half of 1944 saw Magnussen receive several deliveries of eyes taken from Auschwitz victims. A Hungarian prisoner pathologist working as a slave laborer for Mengele in Auschwitz, Miklós Nyiszli, noted after the autopsy of Sinti twins that they died not because of illness but because of a chloroform injection to the heart. Nyiszli had to prepare their eyes and send them to the KWI-A.

At least until the spring of 1945, Magnussen was known to be working in Berlin. After World War II, she moved to Bremen again and continued her research, which was published in 1949 as On the Relationship between Histological Distribution of Pigment, Iris Color and Pigmentation of the Eyeball of the Human Eye. At least in the Soviet Zone of Occupation, Magnussen’s publications appeared on the list of prohibited literature.

In September 1946, the Berlin office of the U.S. Counsel for War Crimes and its chief research analyst, Manfred Wolfson, recommended that both von Verschuer and Magnussen be arrested. British and American officials decided to permit the resumption of German medical science and to forego the prosecution of other crimes. The Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes were too heavily implicated with the Nazi programs of racism, death, and pseudoscience, and the KWI was renamed as the Max Plank Institute. A commission was set up to investigate charges against von Verschuer. Led by a judge, four members of the commission looked not only at specific guilt but also at the scientific value of Verschuer’s work. They determined that his link to Auschwitz crimes was established, and he was judged to be a “racist fanatic.” Verschuer’s career at the KWI-A now ended, he counterattacked that the denunciations derived from “communist agents.”

Wolfson recommended that Magnussen be arrested and interrogated. Those adjudicating at the Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial decided that publicizing German medical atrocities could undermine public confidence in clinical science. In order to avoid the appearance that the entire German medical community could no longer be trusted, the tribunal presented medical researchers as having been “perverted” by the manipulative control of the SS and as poisoned by Nazism. It stated that the human experiments were so ill conceived as not to be worthy of the status of science. The tribunal held further that any additional investigation of hospitals and universities was undesirable, because, if undertaken on a large scale, it might result in the removal of large numbers of highly qualified medical personnel at a time when their services were most needed.

On September 19, 1949, the Dahlem Commission, a tribunal of von Verschuer’s peers, reversed the prior findings of the Nuremberg Doctors’ Tribunal and cleared von Verschuer. It also played down the significance of the Mengele link by stressing that Mengele was only a camp doctor who would have followed SS regulations against spreading information about Auschwitz as an extermination camp. Thus, they ruled that the ties of the German medical community—especially those at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes—were not in any way linked with the death camps and the SS and that medical personnel, such as Mengele, who were directly involved with the death camps were identified as the most responsible for the atrocities of National Socialism.

Karin Magnussen wanted to continue to study the eyes of Roma but was advised to refrain from every attempt to publish her material on this subject for the time being, as there were still Auschwitz Roma victims who could implicate her. Efforts to explore her culpability continued throughout the rest of her life, but she was able to live to almost 90 without any public acknowledgment of her involvement with Auschwitz.

In 1949, scientific-journal editor Alfred Kuhn refused to provide Magnussen a vehicle for her research data on eyes. In rejecting her work, Kuhn stated that “we have discovered that you also worked with human material on Gypsy eyes from the Auschwitz camp in KWI for Anthropology. It is inconceivable to me how it is possible to have a relationship of any kind with a person connected with this institution.”

Both Otmar von Verschuer and Karin Magnussen carried out research on human material supplied by Josef Mengele from Auschwitz. Verschuer apparently preferred not to ask for any details about the circumstances under which Mengele had obtained his material. Magnussen, on the other hand, effectively egged Mengele on. Publicly, at least, she never demonstrated any contrition for the part she played in the atrocities that took place at Auschwitz.

With the end of World War II, Karin Magnussen taught biology at a Bremen grammar school for girls. A popular teacher, she ran interesting classes in which students were able to study live and dead rabbits.

Until 1964, Magnussen published essays in scientific journals. She retired in August 1970, but even in old age, she justified Nazi racial ideology. In 1980, in a conversation with geneticist Benno Müller-Hill, she noted that the Nuremberg Laws did not go far enough. She also denied until the end that Mengele had killed children so that she could continue her research.

In 1990, Magnussen moved into a nursing home. A family member recalled that as Magnussen’s home was being broken up to assist with the move, several jars with eyes from Auschwitz were found, which were then disposed of. Karin Magnussen died in Bremen on February 19, 1997, at the age of 89. Otmar Frieherr von Verschuer remained a respected scientist in Germany and became dean of the University of Münster, as well as an honorary member of numerous scientific societies.

Maria Mandl (also spelled Mandel) was an Austrian SS guard, notorious as a top-ranking official at the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp.

She was born on January 10, 1912, in Münzkirchen, Upper Austria, the third daughter of Franz Mandl, a shoemaker, and his wife Mandlanna. She completed elementary school and then did a year at a commercial school. She spent 18 months abroad with her sister, who was a cook in Switzerland, before becoming a housemaid in Innsbruck. Afterward she worked for the Austrian post office, but following the Anschluss in March 1938, all government employees were dismissed if they had not pledged their loyalty to the NSDAP. Later the same year, Mandl joined the SS, at a time when the SS were looking for single women aged between 21 and 45.

Mandl moved to Munich in September 1938, where, through her uncle who was a police inspector, she became a guard at the SS camp in Lichtenberg, the first women’s concentration camp, on October 15, 1938. She worked here until May 14, 1939. A survivor of Lichtenberg, Linda Haag, recalled only one guard, Mandl, whom she described as standing out from all other guards because of her brutality and violence. She would flog any woman who broke camp rules, tying the naked woman to a wooden post and beating her until she could no longer lift her arms.

From May 15, 1939, to October 6, 1942, Mandl worked as a guard at Ravensbrück, where as a superintendent she assisted Dr. Herta Oberheuser with her search for human experiments. Due to her prior experience, Mandl rose quickly through the ranks. Newly recruited camp guards would begin their training (which could last anywhere between one and six months depending on the recruit’s background), at Ravensbrück, where they were taught how to punish prisoners and how to maintain work speed for those engaged in slave labor.

On January 4, 1941, Mandl became a member of the NSDAP prior to joining the German Women’s League. She was transferred to Auschwitz on October 7, 1942, where she worked until November 30, 1944. She immediately became senior officer of the women’s camp at Birkenau, taking over from Johanna Langefeld, who was dismissed for being too “soft” on Polish prisoners. Mandl was feared and called the “Beast” because of her brutality. A sadistic murderer, she especially liked to select women and children for the gas chambers.

From 1942 onward, Mandl served as the camp leader at Birkenau. Every single female in Auschwitz, prisoner or guard, answered to her, and she answered directly to the commandant, Rudolf Hoess. Mandl’s responsibilities in Auschwitz were to oversee the roll call (which could last up to five hours), selections for killing, and medical experiments conducted by Dr. Josef Mengele.

As a music lover, she developed the women’s orchestra in Birkenau in the spring of 1943. The musicians were treated better than the other inmates; their barracks were clean, and they got better food than other prisoners. The conductor of the women’s orchestra was Alma Rosé, the niece of Gustav Mahler, and the orchestra also included two professional musicians, cellist Anita Lasker-Wallfisch and vocalist/pianist Fania Fénelon, each of whom wrote memoirs of their time in the orchestra. Wallfisch, for example, recollected being told to play Schumann’s Träumerei for Mengele, while Fénelon’s account, Playing for Time, was made into a film of the same name. Mandl’s establishment of the orchestra enhanced her status, both with Mengele, who attended many performances, and with Heinrich Himmler. Fénelon wrote that the orchestra members were scheduled to be shot to death on the same day as their liberation by British troops.

Mandl often had a Jewish prisoner serve as her “personal pet,” carrying out tedious tasks until she was tired of that person—upon which she would have the “pet” executed. When it was time for the prisoners to line up, she would wait for one to look at her, and then she would have that person executed.

Mandl admired Dorothea Binz’s teaching of “malicious pleasure” and was known to have kicked to death a Jewish woman for curling her hair. Any prisoner who dared to look at her risked being sent to the gas chambers. While Mandl was at Auschwitz, she appointed the infamous female guards Irma Grese and Therese Brandl, her private secretary.

With the advance of the Soviet army, Mandl moved camps, and from November 1944 to May 1945, she was a guard at a camp known as Mühldorf. In May 1945, she fled Mühldorf before the advance of the Americans into the mountains of southern Bavaria to her birthplace, Münzkirchen. Her father, who had broken off contact with her when she became a camp guard, would not provide her with refuge. On October 8, 1945, while residing with her sister in Luck, she was arrested by soldiers of the U.S. Army and imprisoned with others in the war crimes prison in Dachau.

On April 4, 1946, the Polish Department of War Crimes sought Maria Mandl’s extradition, and on November 11, 1946, she was delivered into Polish custody and imprisoned in Montelupich prison. On March 5, 1947, her trial began in Kraków; it concluded on December 22, 1947. For her part in the selections for the gas chambers and medical experiments and for her torture of countless prisoners, Maria Mandl was condemned to death as a war criminal by Poland’s Supreme People’s Court. She was executed on January 24, 1948, at the age of 36.

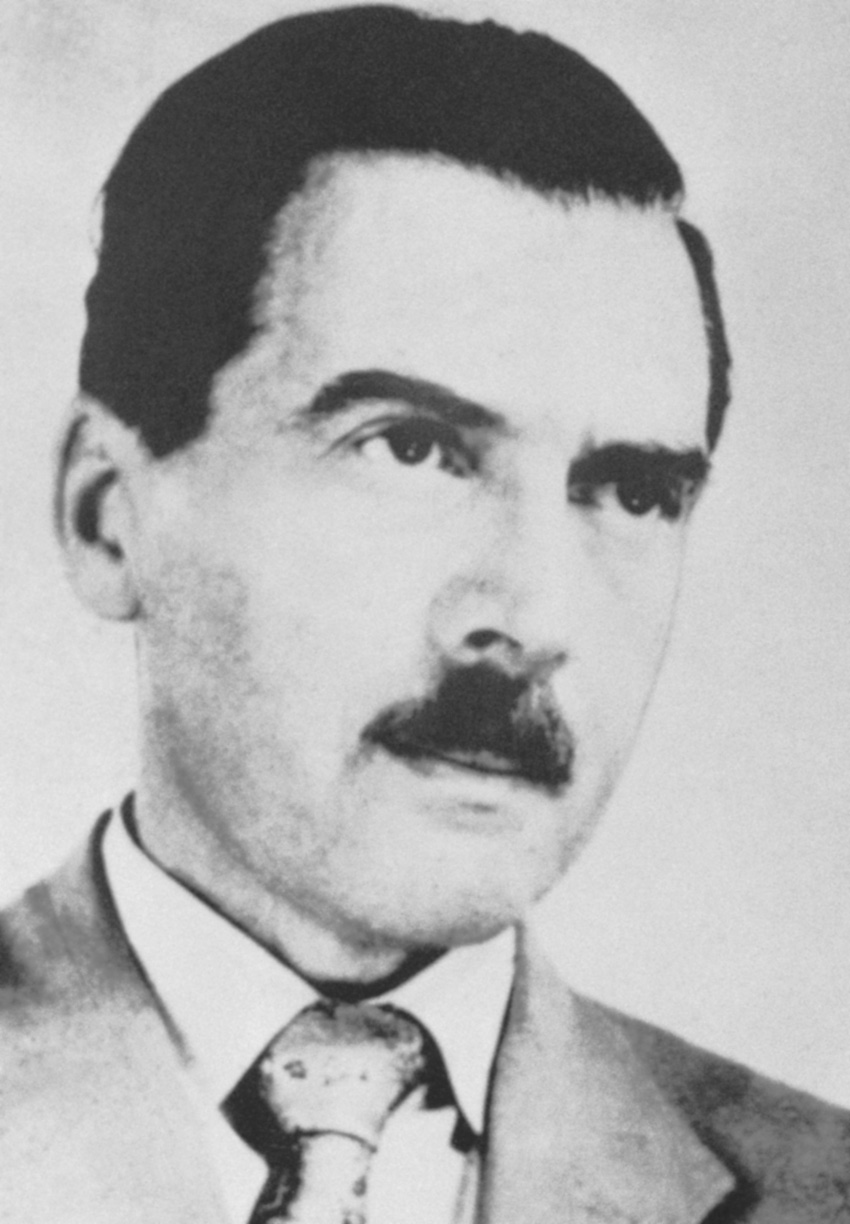

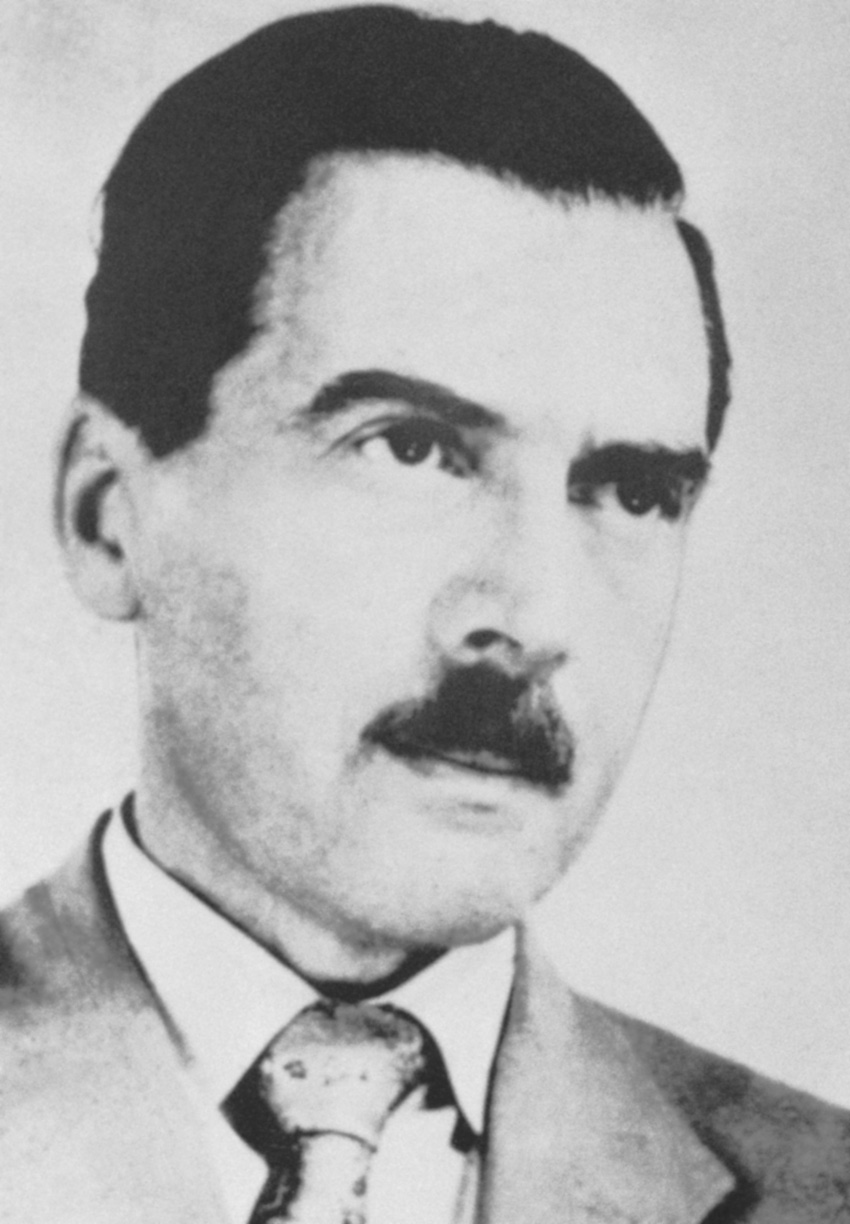

Josef Mengele was an SS physician stationed at Auschwitz during World War II. A member of the team of doctors responsible for the selection of victims to be killed in the gas chambers and for performing deadly human experiments on prisoners, he was nicknamed the “Angel of Death.”

Mengele was born in Günzburg, near Ulm, Bavaria, on March 16, 1911, the oldest of three sons of Walburga and Karl Mengele, a prosperous manufacturer of agricultural implements. As a boy, he was cultured, bright, well liked, and a good scholar. He graduated from Gunzburg High School in 1930 and was accepted into Munich University. With no political interests until this time, he joined the Nazi Party at university to boost his career as a scientist. Mengele joined the Stalhelm (Steel Helmet) militia in 1931; in 1934, the SA incorporated the Stalhelm into its ranks, making Mengele by default a Brown-shirt. Soon after this, Mengele developed a problem with his kidneys that saw him leave the Stalhelm but enabled him to concentrate on his studies. In 1935, he earned a PhD in physical anthropology, with a dissertation that dealt with racial differences in the structure of the lower jaw—allegedly enabling researchers to tell the difference between Jews and non-Jews.

Nicknamed the “Angel of Death,” Josef Mengele was an SS physician stationed at Auschwitz during World War II. Obsessed with the study of human genetics, he was renowned for performing deadly human experiments without anesthetic and overseeing “selections” of arriving prisoners. He was known to conduct experiments on children and was especially fascinated with twins. This image is of Mengele, in 1960, in Paraguay, one of the locations to which he fled after the war. (Bettmann/Getty Images)

In 1936, Mengele passed the state medical examination, after which he went to Leipzig to work at a clinic. In January 1937, he was invited to join the Institute for Hereditary Biology and Racial Hygiene in Frankfurt, where he became the assistant of Dr. Otmar von Verschuer, a leading scientific figure widely known for his research with twins.

Also in 1937, Mengele rejoined the Nazi Party, and in May 1938, he became a member of the SS. On July 28, 1939, he married Irene Schönbein, whom he had met while studying in Leipzig. Upon the outbreak of war in September 1939, Mengele was unable to enlist immediately because of his kidney problem, but in 1940, he was accepted into the Waffen-SS.

In 1941, Lieutenant Mengele was awarded the Iron Cross Second Class in the fighting in Ukraine. In January 1942, he was pronounced unfit for duty, promoted to the rank of captain, awarded the Iron Cross First Class, and posted to the Race and Resettlement Office in Berlin.

On May 24, 1943, Mengele’s next assignment saw him appointed as medical officer of Auschwitz-Birkenau’s Zigeunerfamilienlager (Gypsy Family Camp), where his work was funded by a grant from his mentor, Otmar von Verschuer. Here, he studied human genetics. In August 1944, the camp was liquidated, and all its inmates gassed, after which Mengele became chief medical officer of the main infirmary camp at Birkenau. He was not, however, the chief medical officer of the Auschwitz complex overall; his superior was the SS garrison physician, Eduard Wirths.

SS doctors carried out a selection process on new arrivals to Auschwitz. The doctors “selected” (chose) those who were “fit” for work, while the others (children under 14, the elderly, sick, and women with children) were sent to the line of those picked for immediate death. Some of the SS officers had to get drunk before a selection, but Mengele was reported to enjoy the process and even showed up at selections to which he was not assigned. He was the only doctor as Auschwitz to wear his medals; his uniform was always tailored, and he wore white gloves. He exploited his good looks to trick women into believing whatever he said. He had an unpredictable personality, and everyone, including other SS officers, feared him.

Mengele believed that twins held the mysteries behind how Aryan genetic features, such as blond hair and blue eyes, were passed on. Accordingly, some 1,500 sets of twins were brought to him through the selection process. Once selected, these twins kept their own hair and clothes, were tattooed, were measured in height and weight, and had a brief history taken. In the morning, twins reported for roll call and ate a small breakfast, and Mengele would talk with some of them, give them a candy, or even occasionally play a game.

Life for the twins was bearable until they were taken for experiments. Each day, twins had to give blood—from fingers, limbs, and, for smaller children, from the neck. About 10 cubic centimeters of blood was drawn daily in a painful and frightening process. Sometimes so much blood was drawn that one twin would faint; huge blood transfusions were made from one twin to another. Mengele attempted to change eye color by injecting chemicals or giving drops that caused pain, infections, or temporary or permanent blindness. He injected lethal germs, carried out sex-change operations, and removed organs and limbs, all without anesthesia. He attempted to create Siamese twins by sewing their backs together and trying to connect blood vessels and organs; however, after a few days, gangrene would set in, and the twins inevitably died. Other experiments included isolation endurance, spinal taps without anesthesia, castrations, amputations, the removal of sexual organs, and incestuous impregnations. Some samples of the bodies were sent to von Verschuer for further study. Of the 1,500 pairs of twins chosen by Mengele at Auschwitz, only 200 survived.

Mengele also had an interest in people with physical abnormalities, such as dwarves, midgets, and hunchbacks, and on these, too, he carried out pseudoscientific experiments.

The SS abandoned Auschwitz on January 27, 1945, and Mengele was transferred to Gross Rosen camp in Lower Silesia, working as the camp doctor. After Gross Rosen was evacuated at the end of February 1945, Mengele worked in other camps for a short time, and on May 2, 1945, he joined a Wehrmacht medical unit led by Hans Otto Kahler, his former colleague at the Institute of Hereditary Biology and Racial Hygiene in Bohemia. The unit fled west to avoid capture by the Soviets, and members were taken as prisoners of war by the Americans. Unaware that Mengele’s name already stood on a list of wanted war criminals, however, U.S. officials quickly released him.

From July 1945 until May 1949, Mengele operated under false papers naming him as Fritz Hollmann and worked as a farmhand in a small village near Rosenheim, Bavaria, staying in contact with his wife Irene and an old friend, Hans Sedlmeier. Sedlmeier arranged Mengele’s escape to Argentina via Innsbruck, possibly assisted by the ODESSA network.

In 1954, five years after Mengele escaped to Buenos Aires, his wife Irene divorced him. On July 25, 1958, in Nueva Helvecia, Uruguay, Mengele married Martha Mengele, widow of his deceased brother, Karl. His crimes having been well documented at the International Military Tribunal and other postwar courts, West German authorities issued a warrant for his arrest in 1959. As José Mengele, he received citizenship in Paraguay in 1959. In 1960, a request was issued for his extradition to West Germany. Alarmed by the capture of Adolf Eichmann in Buenos Aires, Mengele moved several times throughout South America, and in 1961, he apparently moved to Brazil, where he lived with Hungarian refugees Geza and Gitta Stammer, working as manager of their farm about 200 kilometers outside São Paulo. In the seclusion of his Brazilian hideaway, Mengele was safe.

In 1974, when his relationship with the Stammer family was coming to an end, other Nazis in hiding, including Hans Ulrich Rudel, discussed relocating Mengele to Bolivia, where he could spend time with Klaus Barbie. Mengele rejected this proposal, preferring to stay in São Paulo for the last years of his life. In 1977, his only son, Rolf, who had never known his father, visited him in São Paulo and found him to be an unrepentant Nazi who claimed that he “had never personally harmed anyone in his whole life.”

Mengele’s health had been deteriorating for years, and he died on February 2, 1979, at a vacation resort in Bertioga, Brazil. He was swimming in the Atlantic Ocean when he suffered a massive stroke and drowned. He was buried in Embu das Artes, under the name Wolfgang Gerhard, whose identity he had used since 1976. These remains were exhumed on June 6, 1985, and a team of forensic experts determined that Mengele had taken Gerhard’s identity, died in 1979 of a stroke while swimming, and was buried under Gerhard’s name. Dental records later confirmed the forensic conclusion.

Mengele had evaded capture for 34 years. After the exhumation, the São Paulo Institute for Forensic Medicine stored his remains and attempted to repatriate them to the remaining Mengele family members, but the family rejected them and turned over his diaries to investigators. The bones have been stored at the São Paulo Institute for Forensic Medicine ever since.

August Miete was an SS officer who worked in the Aktion T-4 program at the Grafeneck and Hadamar euthanasia centers and then at Treblinka extermination camp.

August Wilhelm Miete was born on November 1, 1908, in Westerkappeln, North Rhine-Westphalia, the son of a miller and farmer. He finished school before his father died in 1921. Miete and his brother then took over running the family farm and mill. As an adult, he married and became a family man with three children and remained at the mill and farm until May 1940.

Around this time he expressed interest in becoming one of Germany’s settlers in the conquered East and inquired officially about how this could be achieved. Joining the Nazi Party at once to help realize this, he was drafted into the agricultural service, where he became caretaker of a big property that included a clinic for the insane. After eight days, he was ordered to the Grafeneck euthanasia center, where he remained until the fall of 1940.

Miete then moved on to another euthanasia center at Hadamar, which was still under construction. Becoming involved in the murder process there, he supervised workers who removed and then burned corpses from the gas chambers. He remained at Hadamar until the summer of 1942. At the end of June, he was ordered to Berlin; from there, he was posted to Aktion Reinhard in Lublin and then sent to Treblinka, where he served until November 1943.

He was generally acknowledged to be one of the cruelest of the SS men at Treblinka. The prisoners there nicknamed him the “Angel of Death.” He was assigned by the commandant, SS-Sturmbannführer Christian Wirth, to the train station where new prisoners arrived as well as the undressing yard at Camp I, where he supervised selections for the forced-labor Sonderkommando. He walked among the Jewish prisoners, looking for those fit to work or those who should be dispatched to their death immediately.

An infirmary (Lazaret) had been established at Treblinka, to which these prisoners were taken. All children were also taken, regardless of their state of health. In addition to his other duties, Miete was given charge of the Lazaret, and he carried out most of the killings. He would have each victim stand near a pit in which a fire was always going, take out his gun, and shoot point-blank.

Miete did not act alone in this murderous work. His major accomplice was a junior officer, SS-Unterscharführer Willi Mentz, born in 1904 and known by the prisoners as “Frankenstein.” Mentz, a sawmill worker and milkman before becoming a policeman, joined the NSDAP in 1932. His trajectory was like that of Miete: Grafeneck, Hadamar, and then Treblinka, where he worked at the Lazaret. Mentz wore a white doctor’s coat at the Lazaret, and while serving there, he shot thousands of Jews. In December 1943, Mentz was sent for a period to Sobibór. From there, Mentz served in Italy during Aktion R, killing Jews and partisans.

August Miete, his commander at Treblinka, made it a point for his officers to search each prisoner. Beatings were commonplace and intensified if Miete found items of value. Miete also sought out victims from other parts of the camp to be brought to the Lazaret and shot, and he colluded with other officers, such as Kurt Franz, to find weak, injured, or sick Jews who could be “processed” at the Lazaret. Their fate was foreordained.

With the closure of Treblinka in November 1943, after the end of Aktion Reinhard, Miete was sent to Trieste and, after a brief time there, to Udine, which was under direct German administration after Italy’s surrender to the Allies in September 1943. In the fall of 1944, Miete moved from Udine to upper Italy, attached to a demolition unit.

With the end of the war, Miete was captured by the Americans but was soon released. He returned to the family farm and mill, where he worked until 1950, and then he worked as the managing director of the Savings and Loan Association in Lotte, not far from his original home. He was arrested again on May 27, 1960, and held in pretrial detention at Düsseldorf-Derendorf. On September 3, 1965, he was found guilty at the First Treblinka Trial of participating in the mass murder of at least 300,000 people, as well as of the murder of at least 9 named victims. Miete was sentenced to life imprisonment, but there is uncertainty as to his fate after then. He is believed to have died in prison on July 25, 1978.

Willi Mentz was arrested and charged with complicity in the mass murder of 700,000 Jews during the First Treblinka Trial in 1965. He was sentenced to life imprisonment. On March 31, 1978, he was released from prison due to poor health, and he died on June 25, 1978, in Niedermeien.

Heinrich Müller served as a German police official in both the Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany. As head of the Gestapo, together with his deputy Adolf Eichmann, he directed the investigation, collection, and deportation to ghettos, concentration camps, and death camps of Jews and various other groups deemed socially, racially, and politically undesirable.

Müller was born on April 28, 1900, in Munich, to working-class Catholic parents. In 1918, during World War I, he served as a spotter pilot and was decorated several times for bravery. In 1919, he joined the Bavarian police force. After seeing the revolutionary Red Army shoot their hostages in Munich in April 1919 during the Bavarian Soviet Republic, Müller acquired a hatred of communism and engaged in suppressing communist uprisings in Germany’s turbulent postwar environment. During the Weimar Republic, Müller was appointed head of the Munich Political Police Department, where he met many members of the Nazi Party, including Heinrich Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich. He was not himself yet a Nazi, supporting instead the more dominant Bavarian People’s Party.

On March 9, 1933, during the Nazi takeover of the state of Bavaria that deposed the government of Minister President Heinrich Held, Müller recommended that his superiors use force against the Nazis. Notwithstanding, Müller’s hatred of communism, his professionalism and skill as a policeman, and his firm authority over his subordinates were all qualities that endeared him to Heydrich, even if Müller himself had been reluctant to join the movement. Müller finally joined the Nazi Party in 1939, not because of any ideological convictions but because doing so enhanced his career prospects. That same year, he became chief of the Gestapo, and as “Gestapo Müller,” he implemented Hitler’s policies against Jews and other groups deemed a threat to the state. Eichmann, who headed the Gestapo’s Office of Resettlement and then its Office of Jewish Affairs, was Müller’s immediate subordinate.

Müller was a key participant at the Wannsee Conference on January 20, 1942, at which Heydrich, head of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) and Müller’s superior, announced that Hermann Göring had directed the evolution and implementation of the Final Solution. Under Müller’s management, the Gestapo was instrumental in the deportation process of Europe’s Jews, and Gestapo officials served as vital intelligence links, reporting Einsatzgruppen actions on the Eastern Front to Adolf Hitler.

Müller was also involved in a variety of other criminal and counterespionage matters occurring within the Third Reich. In 1938, he was active in falsifying proceedings against Werner von Blomberg, who had been minister of war since 1935, and Werner von Fritsch, commander in chief of the Wehrmacht, forcing both men from office. In 1939, Müller assisted in fabricating a “Polish” assault on the Gleiwitz radio station, which was used to justify Germany’s attack upon Poland on September 1, 1939, and thereby initiated World War II. In May 1942, Müller also headed up the criminal investigation of Heydrich’s assassination, successfully tracking down his killers.

In March 1944, Müller signed the Bullet Order, which authorized the shooting of escaped prisoners of war. Müller’s quick and harsh interrogation of the members of the July 1944 bomb plot to kill Hitler earned him the Knight’s Cross and the War Service Cross with Swords, conferred in October 1944. Müller was also heavily involved in security and counterintelligence operations that funneled misinformation to the Soviet Union throughout the war. Müller’s Gestapo team caught and turned Soviet agents, which was among the greatest Soviet intelligence setbacks of the war.

Müller was highly regarded for the ruthless efficiency with which he carried out his duties, and although he was late joining the Nazi Party, he remained among the last to leave Hitler’s bunker at the end of the war. He was last seen there on the evening of May 1, 1945, the day after Hitler’s suicide. For a long time, it was thought that he had escaped to Syria, but to this day, his fate remains a mystery despite speculation and investigation by West German police, the Central Intelligence Agency, and British intelligence agencies.