BACH-ZELEWSKI, ERICH VON DEM (1899–1972)

Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski was a senior SS commander who took charge of “bandit fighting” against partisans and others (mostly civilians) designated as a danger to Nazi rule in occupied Eastern Europe. In August 1944, he was instrumental in the suppression of the Warsaw Uprising.

Erich Julius Eberhard von Zelewski was born on March 1, 1899, in Lauenberg (Lębork), Pomerania, to insurance inspector Otto Jan von Zelewski and his wife Elżbieta, of Kashubian gentry background. In 1933, Erich added “von dem Bach” to his surname, and in November 1941, he removed “Zelewski” because of its Polish-sounding origin.

Zelewski’s impoverished father died on April 12, 1911, when his son was just 12 years old. Upon Zelewski’s completion of school in 1914, his uncle persuaded him to join the military, and on November 9, 1914, he enlisted in the German army. He served throughout World War I, was wounded twice, and earned the Iron Cross First and Second Class. In 1916, aged 17, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant.

After the war, Zelewski served in a Freikorps against Polish Silesian rebels. He served as a Reichswehr officer until 1924, when he left the army and returned to his farm in Düringshof (Bogdaniec). He later evinced shame that his three sisters had each married a Jewish man and claimed that this had forced him to leave the army.

He enrolled in and then served with the border guards (Grenzschutz) between 1924 and 1930. On October 23, 1925, he legally changed his surname to von dem Bach-Zelewski.

In 1930, he left the Grenzschutz and joined the Nazi Party. He became a member of the SS in 1931 and attained the rank of SS-Brigadeführer in late 1933. He served as a member of the Reichstag representing Breslau (Wrocław) from 1932 to 1944. After a quarrel with his SS staff officer, Anton von Hohberg und Buchwald, Bach-Zelewski had him killed during the Röhm Putsch on July 2, 1934.

From 1934 on, Bach-Zelewski led SS units, initially in East Prussia and after 1936 in Silesia. In 1937, he was higher SS and police leader (Höherer SS- und Polizeiführer, or HSSPF) in Silesia.

In November 1939, after the German occupation of Poland, SS-Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler offered Bach-Zelewski the role of strengthening Deutschtum (German influence) in Silesia, with responsibility for mass resettlement and the confiscation of Polish private property. By August 1940, as part of Aktion Saybusch, some 18,000 to 20,000 Poles from Żywiec County were forced to leave their homes.

Because Bach-Zelewski’s actions had created overcrowded prisons, his assistant, SS-Oberführer Arpad Wigand, had to find a new location for prisoners. As a result, a concentration camp was created and sited in former Austrian cavalry barracks at Auschwitz (Oświęcim). The first transport arrived there on June 14, 1940, and two weeks later, Bach-Zelewski personally visited the camp.

Later, during Operation Barbarossa, Bach-Zelewski served as HSSPF in occupied Belarus. In 1941, he became a general of the Waffen-SS and was involved in action on the Eastern Front until the end of 1942. During this period, he took part in many atrocities; from July to September 1941, he oversaw the extermination of Jews in Riga and Minsk at the hands of Einsatzgruppe B, led by Arthur Nebe, while also visiting other sites of mass killings, such as Białystok, Grodno, Baranovichi, Mogilev, and Pinsk. He regularly cabled headquarters on the extermination progress; for example, a message on August 22, 1941, stated, “Thus the figure in my area now exceeds the thirty thousand mark.”

While in a Berlin hospital to treat “intestinal ailments” in February 1942, Bach-Zelewski experienced “hallucinations connected with the shooting of Jews.” Before returning to duty in July, he asked Himmler for reassignment to antipartisan duty. Accordingly, through 1943, he took command of antipartisan units on the central front, a special command created by Adolf Hitler. Bach-Zelewski was the only HSSPF in the occupied Soviet territories to retain full authority over the police after Hans-Adolf Prützmann and Friedrich Jeckeln lost their authority to the civil administration.

Sometime in June 1943, Himmler announced the creation of bandit-fighting formations (Bandenkampfverbände), with Bach-Zelewski named as commander. Once the Wehrmacht had secured territorial objectives, the Bandenkampfverbände then ensured the security of communications facilities, roads, railways, and waterways, followed by rural communities and agricultural and forestry resources. The SS oversaw the collection of the harvest, deemed critical to strategic operations. Any Jews or communists in the area were killed. Under Bach-Zelewski, the formations murdered 35,000 civilians in Riga and more than 200,000 in Belarus and eastern Poland. His methods produced a high civilian death toll but relatively minor military gains. After an operation was completed, any military presence was removed, and partisan groups would then resume where they had left off.

In July 1943, Bach-Zelewski took command of all antipartisan actions in Belgium, Belarus, France, the General Government, the Netherlands, Norway, Ukraine, Yugoslavia, and other areas. His major focus of his activities, however, remained confined to Belarus and adjacent parts of Russia.

On August 2, 1944, Bach-Zelewski took charge of all German troops fighting the Polish Home Army of General Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski during the Warsaw Uprising. The German forces were made up of 17,000 men, including the Dirlewanger Brigade of convicted criminals. Units under Bach-Zelewski’s command killed approximately 200,000 civilians, more than 65,000 in mass executions.

Warsaw was destroyed in the process. During the campaign to reduce the city, the Woła massacre occurred—a brutal act of systematic killing by German troops of between 40,000 and 50,000 people in the Woła district of Warsaw. On September 30, 1944, Bach-Zelewski was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross for his actions in Warsaw.

With the end of the war, Bach-Zelewski hid and tried to leave Germany, but on August 1, 1945, he was arrested by U.S. military police. In return for testifying at Nuremberg against his former superiors, Bach-Zelewski was never indicted for war crimes, nor was he extradited to Poland or the USSR. He left prison in 1949.

In 1958, however, Bach-Zelewski was convicted of killing Anton von Hohberg und Buchwald during the Night of the Long Knives back in 1934 and was sentenced to four and a half years’ imprisonment. In 1961, he was arrested again and tried for the murder of six German communists in 1933. He was convicted and sentenced to an additional 10 years in home detention. Neither indictment mentioned his wartime role in Poland and the Soviet Union or his participation in the Holocaust, although he openly accused himself as being a mass murderer.

Bach-Zelewski gave evidence for Adolf Eichmann’s defense in Israel in May 1961, to the effect that operations in Russia and parts of Poland were not subject to the orders of Eichmann’s office nor was Eichmann able to give orders to the officers in charge of these units.

Bach-Zelewski died in a Munich prison on March 8, 1972, a week after his 73rd birthday.

Klaus Barbie, the infamous “Butcher of Lyon,” was head of the Gestapo in Lyon, France, and earned a reputation for his sadism and brutality during World War II.

Nikolaus Klaus Barbie was born into a Roman Catholic family on October 25, 1913, in Bad Godesberg, Germany. His parents were both teachers, and he attended the school where his father taught until moving to a boarding school in Trier in 1923. The family joined him there in 1925. In 1933, Barbie’s brother and his abusive, alcoholic father both died, which thwarted Barbie’s plans to study theology or enter academia. Unemployed, he was drafted into the Nazi labor service (Reichsarbeitsdienst); membership was compulsory for all young German men and women. A strong nationalist, Barbie joined the local Hitler Youth group in April 1933. In September 1935, he joined the Sicherheitsdienst (SD, security service) branch of the SS.

With the outbreak of war in 1939, Barbie rose quickly in the SD. In May 1940, he was sent to the SD office in The Hague, Netherlands. There, his main task was to arrest Jews and German political refugees who fled to the Netherlands, and he organized and participated in mass arrests and deportations of Jews. After his promotion to SS-Obersturmführer, Barbie returned to Germany to be trained in counterinsurgency work. In November 1942, he was sent to Dijon, and after German forces took over Vichy France, he was deployed to Lyon as head of the local Gestapo, in charge of 25 officers. His operational area covered Lyon, the Jura and Hautes-Alpes police departments, and Grenoble.

In Lyon, Barbie became renowned for his brutal policies aimed at French resistance fighters and Jews. He personally tortured prisoners—men, women, and children—and has since been blamed directly for the deaths of 4,000 people. Barbie also oversaw the deportation of Jews to the death camps in the East. In April 1944, he ordered the residents of the Jewish children’s home at Izieu to be transported to Auschwitz. Forty-one children, aged 3 to 11, were gassed.

Barbie’s postwar notoriety came primarily from the arrest and death by torture of Jean Moulin, the highest-ranking member of the French Resistance. Hot needles were shoved under Jean Moulin’s fingernails. His knuckles were broken by catching them in a door hinge and slamming the door until the knuckles broke. His handcuffs were screwed so tightly that they broke through the bones of his wrists. Moulin would not talk; he was whipped and beaten until his face was an unrecognizable pulp. Unconscious and mute, he was shown to other resistance leaders being interrogated at Gestapo headquarters; this was the last time Moulin was seen alive. For this work, Barbie was awarded the First Class Iron Cross with Swords, with the decoration presented by Adolf Hitler himself.

As American forces approached Lyon in August 1944, Barbie ordered the execution of 120 prisoners. Fleeing the city, he later returned to execute 20 former collaborators. After the war, he was recruited by the Western Allies. Initially he worked until 1947 for the British. He was later protected and employed by American intelligence agents because of his “police skills” and anticommunist zeal in being able to infiltrate communist cells in the German Communist Party. In 1949, France requested that Barbie be extradited to stand trial for his crimes. With American assistance in stalling and bureaucratic red tape, Barbie had time to flee to Bolivia with his family in 1951. Assuming the name Klaus Altmann, he remained unidentified for 20 years.

In 1971, Nazi hunters Beate and Serge Klarsfeld succeeded in locating Barbie, but at this time, he enjoyed the protection of Bolivia’s right-wing government. After long negotiations and pressure from France’s socialist government, it was only in February 1983 that the newly elected Bolivian government of Hernán Siles Zuazo arrested and extradited Barbie to France to stand trial.

In 1984, Barbie was notified that he was to be tried for crimes committed while in charge of the Gestapo in Lyon between 1942 and 1944. Many of the charges were dropped due to new laws protecting people accused of crimes under the Vichy regime and in French Algeria.

On May 11, 1987, however, Barbie’s trial in Lyon commenced, a jury trial before the Rhône Cour d’assises. The trial was filmed because of its historical value. The lead defense attorney, Jacques Vergès, argued that Barbie’s actions were no worse than the ordinary actions of colonialists worldwide and that his trial was selective prosecution. During his trial, Barbie stated, “When I stand before the throne of God, I shall be judged innocent.” Overall, he was held responsible for some 26,000 killings. Found guilty on July 4, 1987, he was sentenced to life imprisonment for crimes against humanity. On September 25, 1991, at the age of 77, he died in prison in Lyon of leukemia.

Rudolf Batz was an SS officer who commanded Einsatzkommando 2 in the Baltic and was therefore one of those responsible for the mass murder of Jews in the Baltic States (particularly Latvia) between July 1 and November 4, 1941.

Batz was born in Bad Langensalza, Thuringia, on November 10, 1903. He graduated from school in March 1922 and studied law at the Universities of Munich and Göttingen, graduating in 1934. In the meantime, on May 1, 1933, he joined the Nazi Party. On December 10, 1935, he joined the SS and was assigned to the legal department at Gestapo headquarters in Berlin. In June 1936, he became a deputy Gestapo leader in Breslau (Wrocław), and from the beginning of October the same year, he also served as a political adviser to the government in Breslau. Moving to Linz, Austria, in mid-July 1939, he took charge of the Gestapo there, prior to a further transfer to the state police headquarters in Hanover in December 1939. In 1940, he was promoted to the rank of SS-Sturmbannführer, rising to Obersturmbannführer in 1942.

Although based in Hanover, Batz also received temporary assignments outside Germany. In mid-October 1940, he was sent to The Hague, in the occupied Netherlands, where he served in a security policing function; this lasted until early January 1941. Then in November 1941, he was appointed to command Einsatzkommando 2 (EK2) in Einsatzgruppe A. There were four Einsatzgruppen (mobile killing squads), comprising around 3,000 men, divided into several Einsatzkommandos. Their task was to exterminate Jews, Polish intellectuals, Roma, communists, and other “enemies of the Reich” behind the advancing German combat troops.

EK2 comprised about 40 men. After the start of Operation Barbarossa in the summer of 1941, EK2 was given responsibility for the mass murder of Jews in the Baltic States. Batz’s second in command, Gerhard Freitag, would later testify that Batz presided over the planning and execution of Jewish men, women, and children. In August 1941, Batz and Freitag reported to SS-Brigadeführer Franz Walter Stahlecker (the head of Einsatzgruppe A) that they and their men had exceeded the death toll by up to two or three times that of other units, who were not pulling their weight in the murder process.

During his time with EK2, Batz retained his office in Hannover, but in September 1943, he was sent to Kraków to command the Security Police and Security Service there. In this role, his task was to suppress the Polish resistance movement; where he could, he also organized the deportation of Jews to extermination camps. Two months later, however, in November, he returned to Hanover as head of the Gestapo. Here, he organized the deportation of Jews from the city and its adjacent region. The first transport from Hanover was sent to Riga.

At the beginning of 1945, Batz was transferred to Dortmund as Gestapo head. At this stage of the war, his main role was the control and punishment of forced laborers and anti-Nazi resisters. Under his command, hundreds were murdered.

With the end of the war, Batz assumed a false identity. Married and the father of three children, he lived undetected for 15 years in the Federal Republic of Germany. On November 11, 1960, however, he was arrested and charged with crimes against humanity over his involvement in the mass murder of Jews in Latvia. While in custody awaiting trial, he committed suicide in his prison cell on February 8, 1961.

Erich Bauer was an SS-Oberscharführer at the Sobibór death camp. He was renowned as one of the worst murderers operating in the gas chamber, where he was known as the Gasmeister.

Hermann Erich Bauer was born in Berlin on March 26, 1900. During World War I, he served as a soldier in the German army before being captured by the French and living out the conflict as a prisoner of war. With the ascent to office of the Nazis in 1933, Bauer, at that time a tram conductor, joined the Nazi Party and the SA. In 1940, he began working with the Aktion T-4 euthanasia program, learning how to kill through the introduction of lethal injections and gas those with physical and/or psychological disabilities. At the start, he was assigned duties as a driver, but he moved into other areas of the process as he gained experience and knowledge of the program.

Early in 1942, Bauer received a new assignment when he was transferred to occupied Poland and the Lublin district, under the command of SS- und Polizeiführer Odilo Globocnik. In April 1942, he was deployed to the death camp at Sobibór and given the SS rank of Oberscharführer. He was to remain at Sobibór for the next 19 months, until the camp was closed in December 1943.

Given his experience in the T-4 program, Bauer was placed in charge of gassing procedures in Lager III at Sobibór, while he still drove trucks from time to time. Cruel and uncouth, he was generally remembered as a heavy drinker who cared little for his personal appearance and was frequently unkempt while on duty. He was naturally sadistic toward those under his command and often whipped, beat, and shot at the prisoners. He also kept attack dogs, trained to target the prisoners upon command. As gassings were taking place, he was usually seen on the roof checking the progress of the extermination procedure. It was from this that he picked up the nickname Badmeister (Bath Master); after the war, other survivors remembered he was also called Gasmeister (Gas Master).

Because of his brutality and unpredictability, the prisoner underground identified Bauer as one of the first who would have to be eliminated in the event of any uprising. As things turned out, when the uprising took place on October 14, 1943, Bauer was not present; he had gone to nearby Chełm to search for supplies. Returning sooner than expected, however, Bauer found that another SS-Oberscharführer, Rudolf Beckmann, had already been killed. Bauer opened fire at the two Jewish prisoners unloading his van, and the uprising began in earnest. The result would ultimately see 11 SS officers killed, the camp guards overpowered, the armory seized, and the inmates bursting through the wire and making a break for the forest outside. About 300 out of the 600 inmates managed to escape, with about 60 surviving to see the end of the war.

Within days of the uprising, Heinrich Himmler ordered the Sobibór site closed, the remaining prisoners killed or sent to other death camps, and the guards redeployed. The killing apparatus was to be dismantled, and the site was to be planted with trees.

Bauer was sent to other duties, and when the war ended in 1945, he was arrested by American forces in Austria. Imprisoned through the following year, he was released during 1946 and sent to his native Berlin to clear up debris left by the massive bombing the city had suffered in the last year of the war.

Two former Sobibór prisoners, Samuel Lerer and Esther Raab, recognized him in 1949; he was rearrested and sent for trial in 1950. Despite his protestations of innocence during the trial, Bauer’s claims to have been only a truck driver did not convince any of those in the courtroom. On May 8, 1950, he was sentenced to death for crimes against humanity, a sentence commuted to life imprisonment, owing to the fact that the Federal Republic of Germany had since abolished the death penalty.

Over the next 21 years of his custody in Berlin’s Alt-Moabit Prison, Bauer spoke publicly about his time at Sobibór, admitting his involvement in the mass murders with words such as “I cannot exclude any member of the Sobibór camp staff of taking part in the extermination operation” and “Each of us had at some point carried out every camp duty in Sobibór.”

Erich Bauer died while still serving his sentence in Berlin’s Tegel prison on February 4, 1980.

Kurt Becher was chief of the Economic Department of the SS Command in Hungary during the German occupation in 1944. In this capacity, he negotiated with the Hungarian Jewish community in the failed Blood for Goods initiative, the acquisition of the massive Manfred Weiss industrial complex at Csepel, and the Kasztner train.

Kurt Andreas Ernst Becher was born to a wealthy equestrian family on September 12, 1906, in Hamburg. After completing his education, he worked in a Hamburg food store as a clerk from 1928 until the outbreak of World War II. He was a competent horse breeder and rider, and after the Nazi seizure of power by Adolf Hitler in 1933, Becher joined the Reiter-SS (the SS cavalry regiment) in 1934.

In 1937, Becher became a member of the NSDAP. From 1939 on, he was in the SS- Totenkopfverbände first equestrian unit in Poland. This infamous unit was used in Warsaw and in the war against the Soviet Union after 1941 to fight guerillas. In the fight against resistance fighters in the Pripet Marshes (Belarus), standing orders read that “Every partisan is to be shot. Jews are to be deemed partisans.” During this early phase of the Final Solution, about 14,000 Jews were murdered by Becher’s unit. His promotions were rapid. From SS-Obersturmführer, he was promoted to SS-Hauptsturmführer in mid-March 1942, and then he was transferred to the SS leadership office. In 1944, Becher was promoted twice: first to SS-Sturmbannführer on January 30 and then to SS-Obersturmbannführer in October. That same year, he was awarded the German Cross in Gold.

In the spring of 1944, Becher headed the Waffen-SS Equipment Branch, reporting to Oswald Pohl. Following the German invasion of Hungary in March 1944, Pohl, acting on orders from Heinrich Himmler, sent Becher to Hungary to acquire 20,000 horses and other war material for the Wehrmacht and the Waffen-SS.

Becher played a crucial part in taking control of the massive Manfred Weiss armaments firm at Csepel. Although owned by a Jewish family, it was under majority Aryan control by that family’s non-Jewish members. Both Himmler and Hermann Göring were interested in this enterprise, with its 20,000 workers, coal mines, munitions, and Messerschmitt engine plants. Germany could not appropriate Hungary’s industrial plants, as treaty obligations meant that Germany was not to violate Hungary’s sovereignty; accordingly, negotiations took place between Becher and Ferenc Chorin, representing the Weiss family, over how to proceed.

The agreement reached was mixed. In return for the purchase for 3 million Reichmarks of the Aryan 51 percent controlling share, the SS would permit 46 members of the Weiss family to leave Hungary, taking some of their valuables and foreign currency. Nine of the 46 family members would be held as hostages until the agreement was signed, and the remainder would be given safe passage to neutral Portugal and Switzerland. The nine hostages were to follow on May 17, 1944, the date when the transaction was to be completed. The deal was signed on May 17, 1944.

The 51 percent controlling interest was to be administered by Becher’s holding company for 25 years, and then it would be returned to the Aryan branch of family. Becher and the SS would get 5 percent of the gross income for their service as trustees. This agreement was approved by both Himmler and Adolf Hitler, but it upset Göring, the German Foreign Office, and Döme Sztójay’s Hungarian government, as it removed this massive valuable enterprise from their control.

Becher was also appointed by Adolf Eichmann to head negotiations with Rezső (Rudolf) Kasztner and the Jewish Relief and Rescue Committee of Budapest for ransoming 15,000 Hungarian Jews incarcerated in Bergen-Belsen and their transfer to Switzerland.

On April 25, 1944, Eichmann summoned Rescue Committee member Joel Brand and offered a deal under which the Nazis would “sell” 1 million Jews in exchange for certain goods to be obtained from outside Hungary. In this Blood for Goods scheme, the Jews would not be permitted to remain in Hungary but would be delivered, via Germany, upon receipt of certain goods. Britain called Brand to a meeting in Cairo, imprisoned him in a military prison, and interrogated him for several days.

The mission failed, however, on three grounds. First, the Allies saw this offer as Germany obtaining war material from the Allies; second, the USSR could interpret these discussions as the Western Allies jointly negotiating with the enemy and ignoring the Russians; and third, Germany would use a rejection of the proposal as justification for extreme measures against the Jews. On June 15, 1944, Britain formally briefed the Soviet Union of the proposition, and the USSR immediately vetoed it. On July 19, 1944, the BBC picked up the story and stressed that the “monstrous offer” of the Germans to barter Jews for munitions was a loathsome attempt to blackmail and sow suspicion among the Allies. Kasztner and Joel Brand’s wife, Hansi, were imprisoned in Hungary when Brand failed to return promptly.

On June 14, 1944, Kasztner was informed by Eichmann that he was willing to allow 30,000 Hungarian Jews to be held in Austria as a demonstration of his goodwill. In return, he demanded an immediate payment of 5 million Swiss francs. Eichmann’s offer was based on the instructions he had received from Ernst Kaltenbrunner, head of the RHSA, who was desperate for slave labor to service Austrian industries. The selection of which Jews would be chosen as slave labor was left up to the Jewish leadership. From June 25 to 28, 1944, several transports of approximately 20,000 Jews were directed to Strasshof, a concentration camp near Vienna. About 75 percent of them survived the war.

Kasztner then resumed negotiations with Eichmann to save more Jews. Following discussions with Dieter Wisliceny, Eichmann agreed to allow a special group from Kolozsvár (Cluj) to come to Budapest. Kasztner could not resist the chance to save his family, friends, and most deserving members of the Kolozsvár community, and 338 were taken to Budapest on June 10, 1944. The Jewish Relief and Rescue Committee had to pay Germany a general figure of 5 million Swiss francs, plus 1,000 more for every individual to be included in the transport. About 150 places were “sold” to wealthy individuals. The valuables were delivered to the SS in three suitcases and received by Becher, and the transport left Budapest on June 30, 1944, with 1,684 Jews on board. Certain prominent persons were included, together with many friends and relatives of Relief and Rescue Committee members. They arrived in Bergen-Belsen on July 8, 1944, and were given privileged status.

Kasztner depended on Becher to transport the chosen Hungarian Jews from Bergen-Belsen to Switzerland, in what came to be called the Kasztner Transport. With the approval of Himmler, Becher also met with the head of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee in Switzerland, Saly Mayer, and the War Refugee Board representative, Roswell McClelland, on November 4, 1944. Becher regarded the meeting as highly important, as McClelland represented President Franklin D. Roosevelt. At this meeting, Becher also confirmed that the SS had by now annihilated the Slovakian Jews.

In January 1945, Himmler appointed Becher as special Reich commissioner for all concentration camps. Then on March 11, 1945, he empowered Becher to arrange with Josef Kramer, the commandant of Bergen-Belsen, a cease-fire between the advancing British army and German forces nearby. The camp was surrendered to the British on April 15, 1945.

Becher was arrested by the Allies in May 1945 and imprisoned at Nuremberg, but he was released owing to Kasztner’s intercession on his behalf.

Becher collected large sums of money, jewelry, and precious metals as the war came to an end. Almost all of this came from Hungarian Jews and was estimated at around 8.6 million Swiss francs in what became known as the Becher Deposit. It was alleged that Becher hid this plunder before he was captured, but another explanation is that it was purloined by U.S. troops.

Becher became a prosperous businessman in Bremen and headed the Bremen Stock Exchange with a reported $30 million, making him one of the wealthiest men in West Germany in 1960. He was the president of many corporations, including the Cologne-Handel Gesellschaft, which did extensive business with the Israeli government.

Becher came to public attention once again in 1961, when he served as a witness for the prosecution during the Jerusalem trial of Adolf Eichmann. Becher provided his testimony from his home in Germany, because he was unwilling to travel to Israel itself.

On August 8, 1995, age 86, Becher died in Bremen, reportedly a wealthy man, without ever having to stand trial in court for his deeds.

BECKER-FREYSENG, HERMANN (1910–1961)

Hermann Becker-Freyseng was a German physician who became a medical adviser to the Luftwaffe and participated in medical experiments on Dachau concentration camp internees before and during World War II.

Becker-Freyseng was born in Ludwigshafen, Germany, on July 18, 1910. He graduated as a medical doctor from the University of Berlin in 1935. The following year, he was given the rank of captain in the Medical Service and was posted to the Department of Aviation Medicine. His first important research was his work with Hans-Georg Clamman in 1938 on the physical effects of pure oxygen. Becker-Freyseng became an expert on the effects of high-altitude, low-pressure conditions on human beings.

In 1938, he joined the Nazi Party. Hubertus Strughold, a physiologist and prominent medical researcher who served as chief of aeromedical research for the Luftwaffe, engaged Becker-Freyseng to work in his human-experimentation program. This began a connection in which Becker-Freyseng’s colleagues came to hold him in high esteem. He conducted over 100 experiments on himself, some of which drove him to unconsciousness and the brink of death.

Becker-Freyseng’s key area of experimentation was low-pressure-chamber research. The Department of Aviation Medicine was established in 1936, with Becker-Freyseng initially just attached before he was promoted to coordinator.

Becker-Freyseng’s work in Nazi concentration camps became infamous. He both conducted and supervised several experiments involving unwilling prisoners. Experiments undertaken by him or under his supervision—in particular, the various low-pressure chambers designed to mimic the effects of high-altitude experiments—were performed on inmates of Dachau concentration camp. These often resulted in fatalities. Other experiments recorded the effects of extremely cold temperatures on the human body. One of Becker-Freyseng’s more sinister experiments involved forcing 40 internees to drink salt water to measure their bodies’ reactions. Some also had salt water injected directly into their bloodstreams. The subjects were then subjected to liver biopsies without the benefit of anesthesia to measure that organ’s reaction to the salt water. All subjects of the experiment died.

At the end of World War II in 1945, Becker-Freyseng was taken into custody by U.S. occupation authorities and put on trial for his medical experiments. In 1946, at the Doctors’ Trial, he was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity and sentenced to 20 years in prison. In 1946, however, Becker-Freyseng’s name was on a list with other German doctors, scientists, and engineers as part of Operation Paperclip, a joint British-American operation conducted with the objective of seizing Germany’s top scientists and technologists and transporting them back to Allied countries. Operation Paperclip aimed to prevent these persons from working for the Soviets during the early Cold War period.

Becker-Freyseng was given responsibility for collecting and publishing the research undertaken by him and his colleagues. The resulting book, German Aviation Medicine: World War II, appeared just after Becker-Freyseng began his prison sentence. He was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 1960 and died on August 27, 1961, in Heidelberg, Germany.

Gottlob Berger was a senior Nazi official responsible for SS recruiting during World War II. A zealous antisemite, he was a champion of the Final Solution.

Gottlob Christian Berger was born on July 16, 1896, at Gerstetten, Württemberg, one of eight children of sawmill owners Johannes and Christine Berger. Educated in Nuertingen between 1910 and 1914, he became a physical education teacher. He served in the German army from the start of World War I, was wounded four times, and was awarded the Iron Cross First Class. In 1919, as a first lieutenant, he was discharged as 70 percent disabled. He had three brothers, two of whom died in the trenches of World War I and the other was executed in the United States in September 1918 on a charge of espionage.

Upon demobilization, Berger returned to teaching, but he had trouble adjusting to civilian life. Between 1919 and 1921, he was a leader of the Einwohnerwehr (Citizens’ Defense) militia in North Württemberg. This was a far-right paramilitary organization operating throughout Weimar Germany, established with the goal of defending the country against the possibility of a communist takeover. While engaged in this activity, Berger maintained his gymnastic and physical education interests, and in 1921, now qualified as a sports trainer, he married his fiancée, Maria. Together they would raise a family of four children.

Berger joined the Nazi Party in 1922, and in the spring of 1923, he started a local SA group in his hometown of Gerstetten. After the failed 1923 Beer Hall Putsch and the ban on the NSDAP, he worked as a teacher near Tübingen. He rejoined the Nazi Party in the late 1920s, and in 1931, he joined the SA.

After the Nazi seizure of power in January 1933, Berger led operations involving the roundup of political “undesirables” and Jews. In July 1934, he began work with the head of SA training, Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger. In 1936, on Krüger’s recommendation, Berger was recruited into the Allgemeine-SS by Heinrich Himmler. This saw Berger first assigned as head of regional SS physical education; he was soon transferred to Himmler’s staff as leader of the sports office. In 1938, Himmler appointed Berger to the SS Main Office (SS-Hauptamt, or SS-HA, the central command office of the SS), to head up recruitment.

Berger set the Waffen-SS on a sound basis. His recruiting methods allowed the Waffen-SS to sidestep Wehrmacht controls over conscription. With the onset of war, he managed to extend Waffen-SS recruiting to “Germanic” volunteers from Scandinavia and Western Europe. From here, he recruited Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans) from outside the Reich. Others would follow in succeeding years.

Berger sponsored and shielded his friend Oskar Dirlewanger, whom he placed in charge of a unit of convicts that later perpetrated war crimes. Berger’s recruiting methods upset senior officers of the Wehrmacht and the Waffen-SS, but by the end of the war, the latter had grown to an impressive total of 38 divisions.

Within the SS, Berger was known as one of Himmler’s “Twelve Apostles,” nicknamed der Allmächtige Gottlob (“the Almighty Gottlob,” a play on “Almighty God”), for his closeness to the Reichsführer and because he was one of 12 leading Nazis who dabbled in Völkish spirituality.

Berger ran the SS-HA office in Berlin from 1940 and was heavily involved in activities relating to “Eastern Territories.” The year 1942 saw the publication of the pamphlet Der Untermensch (The Sub-Human), which Berger coauthored with Himmler. It was written to assist soldiers after the start of Operation Barbarossa in June 1941 and described those the Nazis were in the process of conquering as spiritually and mentally lower than animals.

On March 6, 1942, Himmler transferred to Berger the responsibility of recruiting more Waffen-SS divisions, together with police units and guard battalions, along with the establishment, leadership, and training of various SS units in other parts of Europe.

On July 28, 1942, Himmler wrote to Berger that Adolf Hitler had given him instructions that the occupied eastern territories must become free of Jews and that Himmler was to be personally responsible for this task.

On August 10, 1942, while continuing in his role as chief of the SS-HA, Berger was selected to be chief of political operations in the occupied eastern territories. This appointment, which lasted until January 1945, enabled the SS to incapacitate any resistance to SS domination in Eastern Europe. Berger now proposed a plan to kidnap and enslave 50,000 Eastern European children between the ages of 10 and 14, under the codename Heuaktion (Operation Hay Harvesting). On June 14, 1944, Alfred Rosenberg issued orders implementing Berger’s idea, and the plan was carried out.

Berger was also present when Himmler spoke, on October 4, 1943, to a secret meeting of SS officers in Posen (Poznań), in occupied Poland, that Germany was exterminating the Jews.

On July 20, 1944, Berger was given responsibility for the administration of German prisoner-of-war camps. Following the failed attempt on Hitler’s life that same day, the Führer turned to Himmler to head the Replacement Army (Ersatzheer), providing fill-in troops for the combat divisions of the regular army. Himmler quickly delegated his responsibility over the prisoner-of-war camps to Berger, who, in turn, allowed the camps to continue as they were, with the same staff and procedures.

In August 1944, Berger was deployed to serve as military commander of German troops in Slovakia dealing with the Slovak National Uprising. The Slovakian government had until now been procrastinating over the deportation of Slovak Jews, and when Himmler nominated Hermann Höfle as the officer to suppress the revolt, Berger relinquished the role of military commander on September 19, 1944. Deportations of Jews then resumed, and between September 1944 and March 1945, 11 transports deported 8,000 Slovak Jews to Auschwitz, another 2,700 to Sachsenhausen, and 1,600 to Terezín (Theresienstadt).

Berger was then appointed as one of two chiefs of staff to organize the Volkssturm (Home Guard) in Germany. In the final months of the war, he commanded German forces in the Bavarian Alps, which included remnants of several of the Waffen-SS units he had helped recruit. He surrendered to U.S. troops near Berchtesgaden and was promptly arrested.

Berger was put on trial in the Ministries Trial at Nuremberg in 1947. He claimed that he knew nothing about the Final Solution until after the war, even though it was proved that he had been present at Himmler’s 1943 Posen speech. Berger’s defense counsel attempted to mitigate Berger’s actions by claiming that the Cold War bore strong parallels to the Nazi fight against “Jews and Bolsheviks” and that it was possible that the United States would soon have to fight the Soviet Union. Berger, for his part, displayed no remorse for his actions.

In 1949, Berger was convicted for war crimes and crimes against humanity, atrocities, and offences committed against civilian populations. His conviction included being involved with the SS-Sonderkommando Dirlewanger, being a conscious participant in the concentration camp program, conscripting nationals of other countries, transporting Hungarian Jews to concentration camps, and recruiting concentration camp guards. He was also convicted under the charge of using child and youth slave labor, including the Heuaktion.

Given credit for the nearly 4 years during which he had been in custody awaiting trial, Berger was sentenced to 25 years in prison. On January 31, 1951, his sentence was commuted to 10 years’ imprisonment on the dual grounds that he had intervened to save the lives of Allied officers and men who were due for execution and that he had saved 21 Prominente prisoners from Colditz, including Viscount Lascelles and the Master of Elphinstone (both nephews of King George VI), and Giles Romilly, a nephew of British prime minister Winston Churchill. Berger arranged for them to be evacuated from Colditz and transported south, where they were handed over to advancing U.S. Army troops.

Gottlob Berger was released from Landsberg prison in December 1951 after serving six and a half years. He died at the age of 77 in his hometown of Gerstetten on January 5, 1975.

Dr. Karl Rudolf Werner Best was a German jurist, police chief, SS-Obergruppenführer, and Nazi Party leader from Darmstadt, Hesse. As a leading constitutional theoretician and jurist in the Third Reich, he gave respectability and legitimacy to the political police and the concentration camps. He considered that as long as the Gestapo was carrying out the will of the Führer, it was acting legally.

Best was born on July 10, 1903, in Darmstadt. In 1912, his parents moved to Dortmund and then to Mainz, where he completed his education. His father, a senior postmaster, was killed during the first few days of World War I. After the war, Best founded the first local group of the German National Youth League and became active in the Mainz group of the German National People’s Party. In his involvement with the German youth movement, Best was inspired by its return to nature, its Germanic legends, and its Völkish worldview.

From 1921 to 1925, he studied law at Frankfurt am Main, Freiburg, Giessen, and Heidelberg, where he received his doctorate in 1927. In 1929, he was appointed a judge in Hesse but was forced to resign when the so-called Boxheim documents were found in his possession. The documents bearing Best’s signature set out a blueprint for a Nazi putsch and the subsequent execution of political opponents. The disclosure of the Boxheim documents embarrassed Adolf Hitler at a time when he was seeking power by legal means. Despite this, Best was made police commissioner for Hesse in March 1933, and by July 1933, he was appointed governor.

Over the next six years, Best advanced rapidly, becoming chief legal adviser to the Gestapo and chief of the Bureau of the Secret State Police at the Reich Ministry of the Interior. He helped the Gestapo destroy much of the old Weimar legal system and showed them how to use orders for preventive detention without judicial checks.

In 1934, Hitler decided that his internal opposition in the party had to be eliminated. On June 30, 1934, the SS and Gestapo acted in coordinated mass arrests against Ernst Röhm and the SA in a purge that became known as the Night of the Long Knives. Best was sent to Munich to arrest SA members in the southern part of Germany, and at this time up to 200 people were killed.

By 1935, Best was Reinhard Heydrich’s closest collaborator in building up the Gestapo and the Security Service (SD). Then in April 1936, he assumed a leading role in ideological training for the Gestapo. Using biological metaphors, he described the role of the Gestapo and the political police as fighting “disease” in the national body; among the implied sicknesses were communists, Freemasons, and the churches. Above and behind all these stood the Jews.

On September 27, 1939, the security agencies of the Reich were folded into the new Reich Main Security Office (Reichssicherheitshauptamt, or RSHA), which was placed under Heydrich’s control. Best was made head of Department I: Administration and Legal, dealing with legal and personnel issues relating to the SS and security police. Heydrich and Heinrich Himmler relied on Best to develop and explain legally the activities against enemies of the state and in relation to Nazi Jewish policy. In this capacity, he was charged after the war with complicity in the murder of thousands of Jews and Polish intellectuals.

As a Himmler favorite, Best was being groomed for the very top of the SS, but an internal power struggle saw him dismissed by Reinhard Heydrich in 1939. He left the RHSA on June 12, 1940. He then served for two years as civil administrator in occupied France, involved in fighting the French Resistance and in the deportation of Jews, and in this time period he was nicknamed the “Butcher of Paris.”

In November 1942, Best was appointed the Third Reich’s supreme power in Denmark. In this role, he supervised civilian affairs. He kept this position until the end of the war in May 1945, even after the German military had assumed direct control over the administration of the country on August 29, 1943.

As a response to an increase in sabotage attacks in 1943, Best was instructed by Berlin to deliver a statement to the Danish resistance by eliminating the country’s Jewish population. With limited German troops at his disposal and fearing a civil uprising if he deported 8,000 Danish Jews to certain death, he went about fulfilling Hitler’s order to the letter, although not in the spirit the führer intended.

Best’s urgent and repeated requests for additional SS battalions were not met. During the time in question, from September through early October 1943, all available SS troops had been deployed by Heinrich Himmler to Italy, where they were needed to shore up Benito Mussolini’s puppet regime, and thus could not be spared for Denmark.

Best knew that unless he could mount a swift roundup with surgical precision, requiring ruthless and massive SS involvement, his future career would be in jeopardy. He therefore sent his naval attaché, Georg Duckwitz, to Sweden to arrange safe passage and accommodation for Denmark’s Jews, and then Best himself walked into a Jewish tailor’s shop in Copenhagen and warned the tailor and his family that a roundup of the Jews was imminent and told them to flee. The word then spread quickly through the Jewish community.

Almost all Danish Jews survived the Final Solution by escaping to Sweden, ferried over at night by the boats of their non-Jewish Danish neighbors. Only 477 out of more than 7,000 Danish Jews were finally rounded up by German troops, who were forbidden by Best to break into Jewish apartments. Half-Jews were let go, and patrols were not especially vigilant.

It is arguable that Best undermined the Final Solution outcome not out of an altruistic desire to save human life but out of a pragmatic need to maintain a stable status quo in occupied Denmark and to preserve the Reich’s influence. His success depended on the willingness of the Danish people to save their Jewish neighbors—to refuse to see them as anything but fellow Danes. That, in the end, is perhaps the true miracle of the Danish rescue.

To avoid the deportation of Danes to German concentration camps, the permanent secretary of the ministry of foreign affairs, Nils Svenningsen, proposed in January 1944 the establishment of an internment camp within Denmark. Best accepted this proposal but on the condition that the camp should be built close to the German border. Frøslev prison camp was opened in August 1944. In deliberations on May 3, 1945, when preparing for the impending German defeat, Best then fought to avoid implementation of a scorched earth policy in Denmark.

After the war, Best testified as a witness at the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg and was later extradited to Denmark. In 1948, he was sentenced to death by a Danish court, but his sentence was reduced to five years in prison (of which four years had already been served). This created outrage among the Danish public, and the Supreme Court changed the sentence to 12 years. Best was granted a clemency release in August 1951.

He then returned to West Germany, working for a time in a solicitor’s office and then as a lawyer for Stinnes & Co., one of the largest German trading concerns. In 1958, he was fined 70,000 deutsche marks by a German denazification court for his past actions as a leading SS officer, and in March 1969, Best was held in detention while new investigations were carried out concerning his responsibility for mass murder. He was released in August 1969 on medical grounds, although the accusations were not withdrawn.

In 1972, he was charged again when further war crimes allegations arose, but he was found medically unfit to stand trial and was released. After that, he became part of a network that helped former Nazis. He died on June 23, 1989, in Mülheim.

Hans Biebow was the Nazi chief administrator of the Łódź ghetto in Poland, principally responsible for organizing deportations of Jews from there to the Chełmno extermination camp. During his time at Łódź, the Jewish population of the ghetto disintegrated from 200,000 to less than 1,000. As head of the ghetto’s Judenrat (Jewish Council), Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski had a close, though subordinate, relationship with Biebow and reported directly to him.

Biebow was born on December 18, 1902, in Bremen, Germany, the son of an insurance company director. He graduated from secondary school and commenced work at his father’s district branch of the Stuttgart Insurance Company. That was far from successful, however, as the insurance industry had fared badly in the economic circumstances of the 1920s crash and there was little work available. After working in several jobs in the food industry, he started his own small business in Bremen in the coffee trade.

Following the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, the Nazis created ghettos in major cities in which they forced the Jews to live. One of the largest of these ghettos was in Łódź. Biebow, who was recognized as a skilled administrator by his Nazi Party superiors, became the overseer of the ghetto after it was established in April 1940. Initially, he was put in charge of food stocks but was soon made head of the ghetto government.

It was in this capacity that Biebow realized that the ghetto could make a profit for the Germans. He saw an opportunity to benefit from the establishment of over 100 factories and workshops manned by Jewish slave labor to produce goods for the German war effort. Establishing and leading a German staff of some 250 people, Biebow’s transformation of the ghetto into something more akin to a slave labor camp managed to forestall its liquidation until the summer of 1944.

Biebow was not alone in his conviction that producing goods needed by the German army was the best way for the ghetto to avoid liquidation. Mordecai Chaim Rumkowski, the head of the Łódź ghetto Judenrat, was also convinced that producing needed goods was the only way for the Jews entrapped in the ghetto to survive. Thus, Biebow and Rumkowski had similar goals for a high level of productivity from the ghetto and seemed to have a good working relationship as a result. Rumkowski and the Jewish Council established 117 different workshops that used the Jews as slave labor to help manufacture military equipment for the German front lines. The strategy of running the ghetto as a support for the German army was successful, in that Łódź was the last ghetto in Poland to be liquidated.

Biebow derived significant personal wealth from his unfettered exploitation of slave labor and expropriation of Jewish valuables and property. The Jews were promised food and medical supplies in return for their work in the workshops, but his policy of food distribution was the direct cause of widespread starvation. The quality and quantity were less than minimal, and often large portions were completely spoiled. Ration cards for food were quickly put into effect on June 2, 1940, and by December 1940, all provisions were rationed. Allegedly, Biebow pocketed much of the money allocated to buying enough food, leading tens of thousands of Jews to die from some combination of mass starvation, overcrowding, exposure to the elements, arbitrary shootings and beatings, and disease that was the inevitable result of horrid sanitary conditions.

Biebow brought that same enthusiasm to his task of arranging and transporting thousands of Jews from the ghetto to the Chełmno and Auschwitz extermination camps, even as he was trying to keep ghetto production going for as long as possible. He was ruthlessly efficient and saw that his orders to transport Jews to their death were carried out without delay and unhampered by moral concerns. He also organized the collection of personal possessions and clothing of Jewish victims at Chełmno to be warehoused and eventually sent to Germany.

When it became apparent that Germany was going to lose the war, Adolf Hitler called up German men capable of fighting. This increased the need for trained workers, even if Jewish, and so the factories in the Łódź ghetto continued turning out needed goods and equipment. Yet deportations continued, and the ghetto was completely liquidated by August 1944.

Biebow escaped into hiding in Germany in 1945, but he was recognized by a ghetto survivor in Bremen and subsequently arrested. At his trial from April 23 to April 30, 1947, he was found guilty on all counts and was executed by hanging in Łódź on June 23, 1947.

Born in Hamburg on December 17, 1901, Walther Bierkamp was a lawyer who headed the SiPo and SD in Düsseldorf and who commanded Einsatzgruppe D for a full year across 1942 and 1943.

During 1919 and 1921, Bierkamp was a member of Hamburg’s far-right nationalist Freikorps Bahrenfeld and an active participant in the Kapp Putsch of 1921. He studied law in Göttingen and Hamburg, passing the first state examination in 1924 and the second in 1928. He joined the civil service, where he started as Oberregierungsrat (senior entry-level lawyer). Over time, he became head of the Criminal Investigation Department in Hamburg, and as a public prosecutor, he joined the NSDAP on December 1, 1932. In February 1937, he became chief of Hamburg’s Kripo, and then on April 1, 1939, he entered the SS.

On February 15, 1941, Bierkamp was named inspector of the SiPo and the SD in Düsseldorf, a position he held until September 1941, when his responsibilities were compounded by a move to Paris and he was given the same offices for Belgium and Northern France. He remained on station as Höherer SS- and Polizeiführer (higher SS and police leader, or HSSPF) and held all offices until April 1942. On May 3, 1942, he was promoted to SS-Oberführer and was released on June 24, 1942, before accepting his next command.

On June 30, 1942, Bierkamp relieved Otto Ohlendorf as commander of Einsatzgruppe D in southern Ukraine and Crimea. When the 11th Army began its summer offensive toward the Caucasus, Einsatzgruppe D moved in behind it. In August, the first major action took place against Jews in the region. Gas vans were employed against children from orphanages in Krasnodar and Yeysk as well as residents of Pyatigorsk. Then on August 21 to 22, 500 people were murdered in the Krasnodar Forest, followed by the inhabitants of Mineralnyje Wody on September 1, and the Jews of Yessentuki and Kislovodsk on September 9 to 10. In all, the campaign realized a death toll of more than 6,000 Jews.

By January 4 to 5, 1943, Jewish survivors in the region, who had lived long enough to be used as slave labor, were murdered in Kislovodsk; by then, the number of Jewish victims had grown to about 10,000. In May 1943, to accompany the start of the German army’s summer offensive, Einsatzgruppe D was renamed Kampfgruppe Bierkamp (Bierkamp Combat Group) in honor of their commander. This name was kept for a short time until June 15, 1943, when upon his return from Einsatzgruppe duties, Bierkamp was sent to Kraków as HSSPF for the Generalgouvernement.

As the war situation deteriorated and the Soviets began to advance of Poland, Bierkamp saw that drastic measures would need to be taken if the remaining Jews in the Generalgouvernement were not to fall into Russian hands. Thus, in addition to overseeing the final “cleansing” of the Jews of Kraków, he issued a decree on July 20, 1944, ordering that Jews working at forced labor in the arms industry be immediately transported to death camps. If this was not possible, he demanded that they “will be liquidated on the spot, and their corpses will have to be eliminated by incineration, blasting or by other means.” On November 9, 1944, Bierkamp received his final promotion, to SS-Brigadeführer and police major general.

In this capacity, he was sent to command police and security services in Stuttgart until February 20, 1945, when he was sent as HSSPF to Breslau (Wrocław), where he took over on March 17, 1945. With the further advance of the Russians, the territory he was controlling was largely overrun; although by his title, he remained HSSPF Southwest until mid-April 1945. From April 14, 1945, until the war’s end, Bierkamp was stationed in Hamburg.

On the night of May 15 to 16, 1945, Walther Bierkamp committed suicide in Scharbeutz, a municipality in Schleswig-Holstein not far from the city of Lübeck.

Herbertus Bikker was a Dutch member of the Waffen-SS who served as a prison guard at Camp Erika near Ommen from June 19, 1941, until April 11, 1945.

He was born into a large farming family on July 15, 1915, in Wijngaarden, the Netherlands. His mother died when he was six years old. His father gave him a strict education, but as he had to help on the farm, he only completed primary school. Prior to World War II, he became a member of the Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging in Nederland (National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands, or NSB), and in early 1940, Bikker was imprisoned by the Dutch police for security reasons. After the German occupation of the Netherlands, he was released.

In 1941, with the start of Operation Barbarossa, Bikker enlisted as a Dutch volunteer in the Waffen-SS and served on the Eastern Front. When wounded, he was discharged from further military service and returned to the Netherlands.

Between July 1942 and May 1943, Bikker was put in charge of the Control Commando, which ran Kamp Erika. By 1943, he had recovered from his war wounds, and as a member of the Ordnungspolizei (uniformed Nazi police), he served in Nijmegen, Tiel, and Maastricht. In August 1944, he returned to Kamp Erika. A later report, by Jan Meulink for the Ministry of Justice, stated that Bikker abused his prisoners; Meulink noted that witnesses described him as “a plague, by the way he hit prisoners, mistreated with a carabiner, or stamped” on them, crippling healthy inmates. For his actions in hunting down resistance fighters and for his brutal behavior toward inmates, he was known as the “Butcher of Omman.” He was responsible for the murder of 27-year-old Dutch resistance fighter Jan Houtman, who was killed on November 17, 1944, and the death of another resistance fighter, Herman Meijer, on October 12, 1944.

On May 10, 1945, Bikker was arrested by the Dutch army, but he escaped and worked with a farmer until discovered in late 1945. In June 1949, he received the death penalty for his crimes as a guard in Kamp Erika, including torture, deportation, and treason, as well as two murders. The punishment was converted to life imprisonment on December 7, 1949.

On December 26, 1952, Bikker, along with several other criminals, escaped from the Dome Prison in Breda, and that night they crossed the border into West Germany, where they reported to the police. The next day a German district court judge fined them 10 deutsche marks for illegal crossing. Under a decree from 1943, foreign members of the Waffen-SS automatically received German nationality, and as Germany did not extradite its own nationals, Bikker, with German citizenship, fell outside the grasp of Dutch justice.

In 1957, Bikker was summoned to appear before a Dortmund court, but the case was discontinued due to “lack of evidence.” Dutch courts were reluctant to hand over their evidence to German courts, because they distrusted the many former Nazi judges who had continued in their posts after the fall of the Third Reich. Bikker allegedly also received assistance in Germany from former SS members who were once again occupying influential positions.

In 1972, Bikker threatened the Dutch investigative journalist Ben Herbergs with an ax in a barn behind Bikker’s home in Hagen, Westphalia. Herbergs had located Bikker in Germany after a political uproar had arisen in the Netherlands about the freeing of other Nazi war criminals. Bikker had agreed to a “short conversation from fellow countryman to fellow countryman” with the Dutch reporter and a German photographer, and he spoke frankly about his work and his illegal family visits to the Netherlands. When he discovered a tape-recording device with loose microphone cable, Bikker flew into a rage; he grabbed heavy tools and an ax and barred the access door, but the Dutch reporting team escaped.

For decades, prosecutors sought Bikker’s return. In 1994, a Dutch journalist and Nazi hunter, Jack Koistra, traced Bikker to his residence in Hagen. After this was reported on Dutch television, the Dutch minister of justice sought Bikker’s immediate extradition; this was again rejected by German authorities. In November 1995, German and Dutch members of anti-fascist groups, together with a few surviving resistance fighters, protested outside Bikker’s home, shouting that “Herbertus Bikker is a murderer.” The demonstrators were fined for demonstrating without a permit.

Stern editors Werner Schmitz and Albert Eikenaar noted the way this demonstration was handled, and it was due to their investigative journalism that Bikker again came before the courts. But it was Bikker’s own boast, in a 1997 interview with Schmitz, of having shot Jan Houtman that started a lawsuit against him. Describing the events on November 17, 1944, Bikker told Schmitz that he gave Houtman “the final shot.” After the publication of the Stern interview in 1997, chief prosecutor Ulrich Maass from the Nazi crimes central office began investigations at the state attorney’s office in Dortmund.

It took another six years before the case commenced. In the meantime, some of the eyewitnesses to Jan Houtman’s murder had died. Houtman’s widow had also died three years earlier. But an important witness, who had already provided written evidence five years previously, was able to appear at the district court in Hagen on October 10, 2003, to testify.

On September 8, 2003, in the German district court of Hagen, almost 59 years after Jan Houtman’s murder, the trial of the now 88-year-old Herbertus Bikker opened. He stood accused of shooting Houtman to death on November 17, 1944. The indictment read that Houtman had been injured trying to escape a labor camp and was lying on the floor of a nearby barn when Bikker caught up with him, pulled out his pistol, and shot Houtman saying, “And now a good death.” Bikker’s only chance to evade prosecution and trial was to claim diminished responsibility due to illness. When a doctor attested that Bikker was medically fit to stand trial, his case came to court. However, after Bikker had a breakdown and fainted in court, neurologists advised against him standing trial due to illness. For that reason, the hearing was adjourned on February 2, 2004.

Bikker lived in Hagen as a pensioner until his death on November 1, 2008, in Haspe, Germany. His passing was not announced until April 2009.

The trial shed light on the brutal occupation of the Netherlands by Adolf Hitler’s National Socialist regime and the terrible consequences resistance fighters suffered at the hands of both the military secret service and their Dutch collaborators. That so much time elapsed before Bikker was obliged to stand trial showed the diffident attitude of German authorities to those responsible for Nazi crimes.

Dorothea Binz was a prison guard at Ravensbrück concentration camp during World War II, where she gained a reputation as one of the most brutal women within the Nazi system.

Dorothea “Theodora” Binz was born on March 16, 1920, in Gross-Dölln, Brandenburg, to a German middle-class family. The middle daughter of Walter Binz, she attended school until she was 15, missing much schooling along the way due to tuberculosis. Upon leaving school, she worked for a while as a kitchen aide and then as a housekeeper, which she is reputed to have hated.

Physically, she had beautiful blond hair and blue eyes, the ideal of the Nazi woman. Binz joined the Bund deutscher Mädel (League of German Girls, or BdM), the female counterpart of the Hitler Youth (Hitlerjugend), and became influenced by Nazi doctrine. She wanted to join the SS and applied for a job as a kitchen hand in the women’s camp at Ravensbrück in August 1939. On September 1, 1939, she was sent to Ravensbrück to undergo training as a guard. During her time there, at least 50,000 women died.

The senior officers under whom Binz served included Emma Anna Maria Zimmer, Johanna Langefeld, Maria Mandl, and Anna Klein-Plaubel. At times, she worked with Dr. Herta Oberheuser and the Polish prisoners (nicknamed “the rabbits”) at Ravensbrück in various parts of the camp, including the kitchen and the laundry. After 1942, she oversaw the training of new guards at Ravensbrück. In August 1943, she was promoted to deputy chief wardress. As a member of the command staff between 1943 and 1945, she directed training and assigned duties to over 100 female guards and introduced training for recruits destined for other concentration camps, such as Buchenwald and Auschwitz-Birkenau. Binz reportedly trained some of the cruelest female guards in the system, including Ruth Closius-Neudeck and Irma Grese.

Binz supposedly supervised the bunker where women prisoners were tortured and killed. She earned the reputation of being sadistic and of being extremely cruel. Smashing heads and shooting or maltreating prisoners for no apparent reason (and often for no reason at all) became a daily occurrence; it appears that she fully enjoyed her abuse of power. She would walk through the camp with a whip in one hand and her leashed German shepherd dog in the other. She could kick a prisoner to death with her heavy boots or choose to have the prisoner executed, and she was especially cruel to Soviet prisoners of war, whom she dubbed “Russian pigs.” Binz maintained a special truck to take prisoners to the gallows and took pleasure in watching their death.

While at Ravensbrück, she had an affair with a young married SS officer, Edmund Bräuning, and their favorite pastimes included “romantic” walks through the camp, arm in arm or hand in hand, as they showed amusement at seeing women who were flogged. Stripped prisoners went to Ravensbrück’s “bunker”—torture cells—where they were handed over to Binz and her junior officers. Camp survivors testified how Binz and her team regularly tortured prisoners by immersing them in ice-cold water.

As the Allies advanced in 1945, Ravensbrück was evacuated. Survivors were sent on a death march, from which Binz fled, but she was caught by British troops in Hamburg on May 3, 1945. She was imprisoned for a time in Recklinghausen, a subcamp of Buchenwald, until she was tried with other SS and camp personnel by a British court at the Ravensbrück War Crimes Trials. She was convicted of perpetrating war crimes and sentenced to death by hanging. On May 2, 1947, the sentence was carried out in the prison of Hameln by British hangman Albert Pierrepoint. To avoid any signs of martyrdom, the bodies of Binz and the others were buried in the Hamelin prison yard. In 1954, the bodies were reburied in holy ground at Am Wehl Cemetery. Originally the graves had iron crosses placed over them, but after a succession of visits from neo-Nazis, all 200 crosses were removed on March 3, 1986. The graveyard is now a grass field.

Paul Blobel was an SS commander who led Sonderkommando 4a (a part of Einstazgruppe C), which became notorious for the mass murder in 1941 of 33,771 Jews in Babi Yar, a ravine near Kiev, Ukraine.

He was born on August 13, 1894, in Potsdam, near Berlin, the son of a craftsman. He qualified as a stonemason and carpenter. In World War I, he served in an engineering unit, was awarded the Iron Cross First Class, and in 1918 rose to the rank of staff sergeant.

After demobilization, Blobel studied construction between 1919 and 1920, and from 1921 to 1924, he was employed by various firms as an architect. He opened his own architectural practice in 1924, but because of the Weimar Republic’s economic crisis, he received no new work and lived on a social security allowance between 1930 and 1933. By December 1, 1931, Blobel had joined the Nazi Party, the SA, and the SS. In 1933, he joined the Düsseldorf police force, and in June 1934, he was recruited into Reinhard Heydrich’s SD. On January 30, 1941, he was promoted as chief of the SD in Salzburg, with the rank of SS-Standartenführer.

During the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, Blobel took command of Sonderkommando 4a of Einsatzgruppe C, then active in Ukraine. Einsatzgruppe C was under the control of Otto Rasch. The role of the Einsatzgruppen (mobile killing units) was to follow troops of the Wehrmacht as they advanced into Ukraine; they were tasked with eliminating political and racial “enemies” of the Third Reich.

Blobel was primarily responsible for carrying out the notorious massacre of 33,771 Kiev Jews at the Babi Yar ravine in Kiev. In August 1941, in Belaya Tserkov, some 50 miles south of Kiev, all adult Jews were murdered by Blobel’s unit. Execution of the children was suspended by a junior officer, Helmuth Groscurth, who drafted a report in which he wrote that the execution of women and children “did not differ in any way from the atrocities perpetrated by the enemy.”

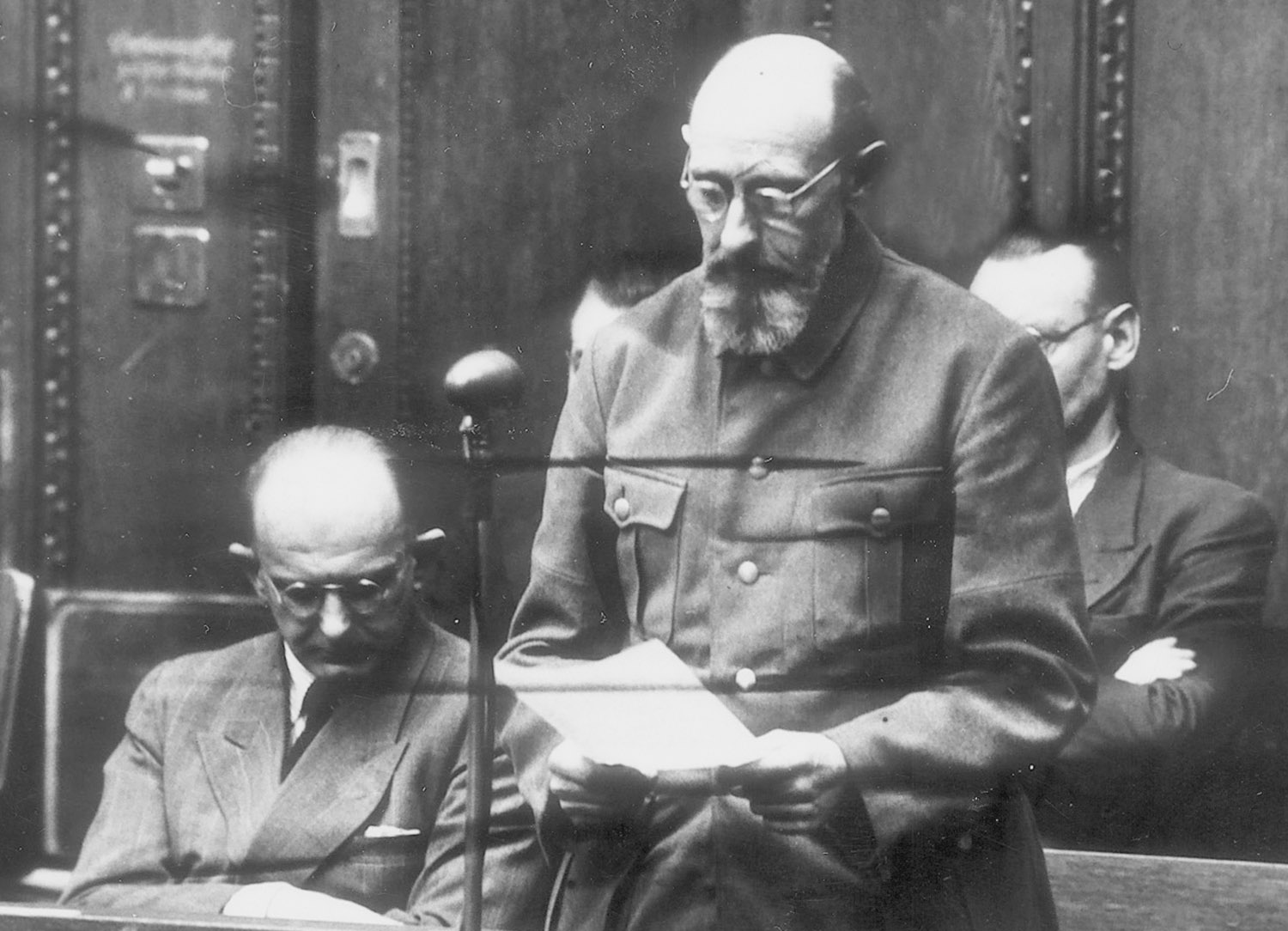

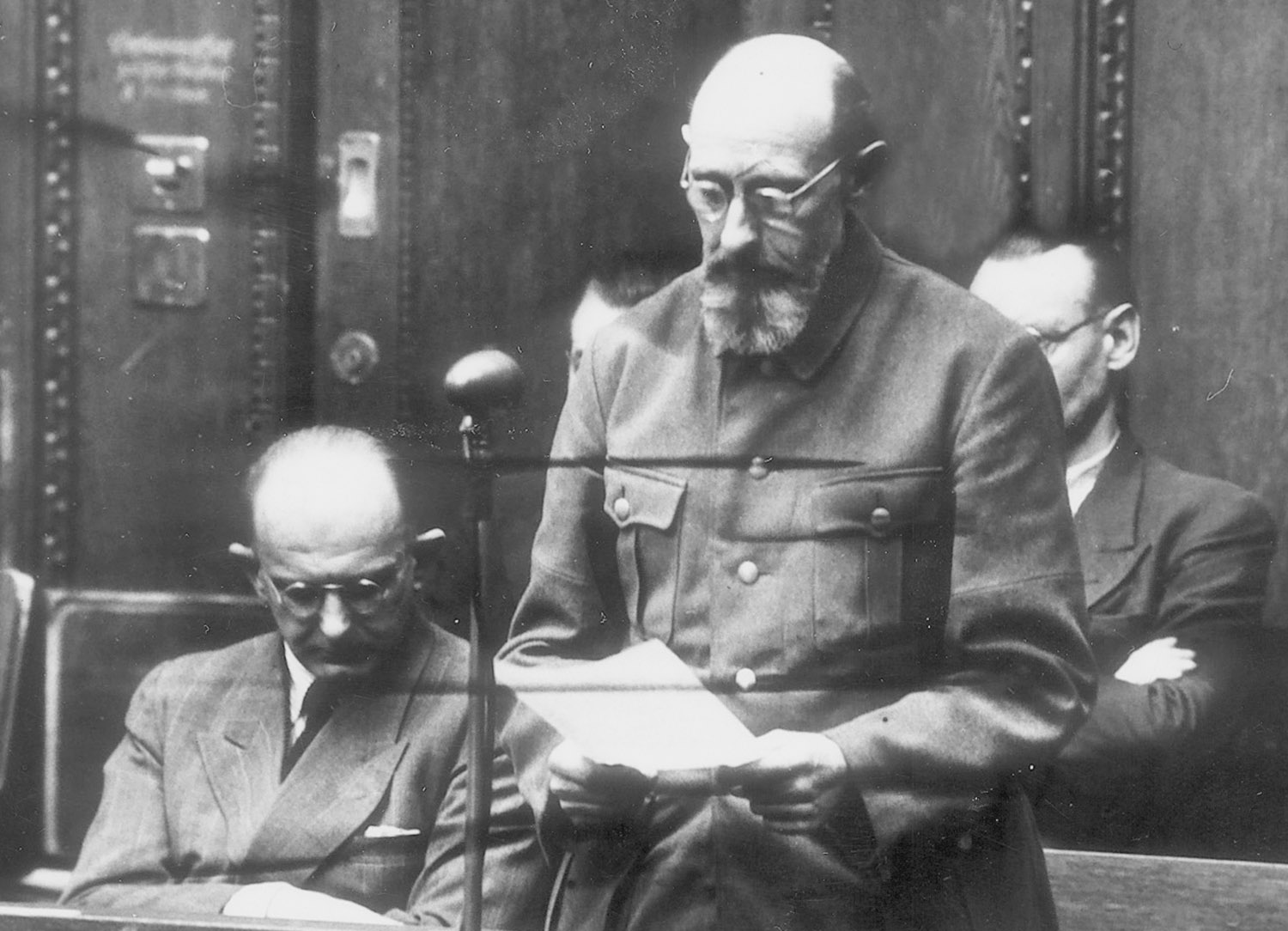

Paul Blobel was an SS commander who led Sonderkommando 4a, which became notorious for the mass murder in 1941 of 33,771 Jews at Babi Yar, a ravine near Kiev, Ukraine. Here, Blobel pleads not guilty during the Einsatzgruppen trial at Nuremberg in 1947. At the left of the photo is another indicted SS commander, Franz Six. (Chronos Dokumentarfilm GmbH/ullstein bild via Getty Images)

His superior officer was Walther von Reichenau, whose position on such matters would be encapsulated on October 10, 1941, in what became known as the Severity Order. Reichenau’s order asserted that German soldiers “must learn fully to appreciate the necessity for the severe but just retribution that must be meted out to the subhuman species of Jewry.” The order paved the way for mass murder of Jews in areas coming under his command, and the expectation was that all Jews would from this point onward be either summarily shot or handed over to the Einsatzgruppen. He thus rejected Groscurth’s concerns and stated that the argument should never have been written down in the first place. Blobel and his assistant, August Häfner, had already told Groscurth that execution of the children had to continue. An argument then arose between Blobel and Häfner about who should carry out their murder; Häfner said his troops had their own children and should not be forced to carry out this cruel act. He suggested that von Reichenau’s Ukrainian field militia should execute the children, which they did.

Shortly after the children of Belya Tserkov had been executed, Blobel and his Sonderkommando arrived in Kiev. The Soviet security service (NKVD) had bombed the city center during the battle for control of the city, and as a result, many German soldiers had died. In reprisal, Blobel determined that the Kiev Jews would be exterminated, even though they—mainly the elderly, women, and children—could in no way be blamed for the bombing. On September 29, 1941, all Jews were ordered to congregate and told that they would be deported to labor camps. Instead, they were shot into in a ravine at Babi Yar, northwest of the city. In his progress report dated October 7, 1941, Blobel reported the execution of 33,771 Jews there.

Following the mass murder at Babi Yar, a gas van was made available to Blobel’s Sonderkommando. Einsatzgruppe C was issued at least five gas vans and gave two to Sonderkommando 4a, two to Einsatzkommando 6, and one to Einsatzkommando 5. From June 1941 to the end of 1943, 59,018 people were murdered by Sonderkommando 4a, although after January 13, 1942, this was no longer done under Blobel’s command. He was removed by his successor, SS-Oberführer Erwin Weinmann, who had him transferred to Berlin for disciplinary reasons (probably related to Blobel’s excessive drinking). Once there, he was not given an immediate assignment and was placed under the supervision of the Gestapo chief Heinrich Müller.

During 1942, SS-Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler decided that the buried remains of Jews and other victims of the Einsatzgruppen had to be cleared away. The same had to be done with victims of the extermination camps who had not been cremated but buried in mass graves. Reinhard Heydrich was charged with this operation, and in 1942, he met with Blobel to discuss the nature of the operation that now had to take place. Blobel’s commission was suspended by Heydrich’s death on June 4, 1942, but later that month, he was officially ordered by Heinrich Müller to take charge of the operation, which was top secret and codenamed Aktion 1005.

Before the exhumations could be started, a suitable method had to be found for destroying the corpses. The place chosen for trials was Chełmno, the first death camp, which had been operating since the end of 1941. Aktion 1005 would take place by disinterring and cremating the bodies in wood fires in open pits. The bones were crushed in a special machine, and the ashes and any remaining bone fragments were buried in the graves from where the corpses had originally been exhumed. With a suitable method now found for erasing the traces of mass extermination easily and efficiently, the operation could begin in earnest and was carried out by Sonderkommando 1005—a special unit of about 20 men, members of the SS, SiPo, and other police forces under Blobel’s command.

Blobel’s last role in the Third Reich was commanding Einsatzgruppe Iltis, a unit consisting of two Einsatzkommandos tasked with fighting partisans on the Austro-Yugoslav border. Several of his men had already served under him in Sonderkommando 1005; after the war, he alleged that he himself had not been active as leader of Einsatzgruppe Iltis, as he had fallen ill in 1944 (his drinking had developed into alcoholism) and been confined to a sanatorium from February to April.

At the beginning of May 1945, Blobel was apprehended by the Americans. Placed on trial at Nuremberg, he protested his innocence, but he was nonetheless found guilty of crimes against humanity, war crimes, and membership of illegal organizations. He was sentenced to death. During the trial, he showed no remorse and only allowed expressions of compassion for the perpetrators who had been tasked with this dirty work. He was executed by hanging in Landsberg Prison on June 7, 1951.

A high-ranking Nazi doctor and research scientist, Kurt Blome controlled unethical medical experiments on concentration camp prisoners. Captured by U.S. forces, he was acquitted at the Doctors’ Trial in 1947 and worked with U.S. scientists to impart his knowledge of bacteriological warfare and biological weapons from these experiments.

He was born in Bielefeld, Germany, on January 31, 1894, and graduated from high school in Dortmund. He moved to Rostock in early 1914 to study medicine at the University of Göttingen. On April 1, 1914, he began his compulsory military service with the Mecklenburg Fusilier Regiment “Kaiser Wilhelm” No. 90. During World War I, he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant. Wounded in March 1918, Blome ended the war as a patient in a Bremen hospital.

From 1918 to 1919, he continued his medical studies in Münster and Giessen and became a member of the Freikorps in Rostock. In 1920, he was actively involved in the so-called Kapp Putsch, in which he was wounded. He passed his medical examination in 1920 in Rostock, and in 1921, he was awarded a doctor of medicine degree at Rostock for his work on the behavior of bacteria.

Blome joined the NSDAP in 1922. In November 1923, after the party had been banned following Adolf Hitler’s abortive putsch, he was dismissed by the University of Rostock owing to his Nazi activities. From 1924 to 1934, he then led a medical practice as a specialist for skin and sex diseases.

In 1934, Blome became director of the Office of Public Health in Mecklenburg-Lübeck. The same year he was appointed to the main office for public health in Berlin as commissioner for the exemption provisions of the Nuremberg Laws. He was later appointed as head of medical training for the Third Reich in January 1935. On February 8, 1936, Blome became a member of the Reich Committee for the Protection of German Blood, and from April 20, 1939, he was deputy head of the Office for National Health.

His appointment on April 30, 1943, as head of the Central Institute for Cancer Research in Nesselstedt near Posen was a camouflage for his work on biological weapons. Blome was also appointed as a member of the Blitzforschung (“lightning research”) working group, which was preparing for biological warfare. An expert on the development of biological weapons, Blome had a long-standing interest in the military use of carcinogenic substances and cancer-causing viruses. He worked on methods for the storage and dispersal of biological agents, like plague, cholera, anthrax, and typhoid, and later he confessed to have infected concentration camp prisoners at Dachau with bubonic plague to test vaccines. Blome was an expert in aerosol dispersants and the transmission of malaria to humans. At Auschwitz, he sprayed nerve agents like Tabun and Sarin from aircraft on prisoners.

In March 1945, Blome fled from Posen (Poznań) just ahead of the Red Army. He was unable to destroy the evidence of his experiments, however, which is why so much is known about them. On May 17, 1945, with the defeat of Germany, Blome was arrested in Munich by American military personnel. He was subsequently tried at the Doctors’ Trial in 1947 on charges of practicing euthanasia and conducting experiments on humans. Inexplicably, he was acquitted; it was rumored that he was saved by American intervention. Two months after his Nuremberg acquittal, Blome was transferred to the United States, where he was interviewed at Camp David, Maryland, about biological warfare.

In 1951, Blome was hired by the U.S. Army Chemical Corps under Project 63 to work on chemical warfare. Although his file did not mention his trial at Nuremberg, Blome was denied a visa to work in the United States. He was, however, employed at the European Command Intelligence Center at Oberursel, West Germany, where he worked on chemical warfare projects. Blome also conducted research on cancer.