Herbert Martin Hagen was an SS-Sturmbannführer with specific responsibilities regarding the Jewish question.

Born on September 20, 1913, in Neumünster, Schleswig-Holstein, he joined the SS in October 1933 in Kiel, where, from May 1934, he was mentored by Franz Six, head of the press office of the Sicherheitsdienst (Security Service, or SD) at the headquarters of SS-Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler. In September 1934, the SD main office moved from Munich to Berlin, with Hagen employed in Central Division I.3 (Press and Museum). From the summer of 1936 onward, he lectured at the German Academy of Politics. At the age of 24, he became one of the youngest service chiefs of the Reich security apparatus.

In 1937, he headed Division II/112 (Jews) at SD headquarters, and in this capacity, he and his subordinate Adolf Eichmann traveled to the British Mandate of Palestine to assess the possibility of Germany’s Jews voluntarily emigrating there. Feival Polkes, an agent of the Haganah, had earlier met with Eichmann in Berlin in February 1937, and it was at his invitation that Hagen and Eichmann went to Palestine. They left Berlin on September 4, 1937, and disembarked at Haifa with forged press credentials on October 3, traveling on to Cairo. Once there, meetings took place on October 10 and 11, 1937, but they were unable to strike a deal. Polkes had hoped that he could negotiate for more Jews to be allowed to leave under the terms of the Haavara (transfer) Agreement of August 25, 1933, but Hagen refused any relaxation, claiming that a strong Jewish presence in Palestine might lead to the establishment of an independent Jewish state. Eichmann and Hagen attempted to return to Palestine a few days later but were denied entry after the British authorities refused them the required visas.

Upon returning to Germany, Hagen moved into the press office of the SD, from where he traveled throughout the country spreading the gospel of Nazi antisemitism. With the Anschluss between Germany and Austria, Hagen and Eichmann journeyed to Vienna to work in the establishment of SD there.

When World War II broke out, the SD, the Gestapo, and the Criminal Investigation Department were brought together under the auspices of the Reichsicherheitshauptamt (Reich Security Main Office, or RSHA) on September 27, 1939. Hagen moved into the RSHA-Amt VI (Foreign Intelligence Service) although he was still involved with RSHA-Amt VI H2 (Jewish Questions and Antisemitism), as he had been earlier.

With the German occupation of France in 1940, Hagen moved to Paris, and on August 1, 1940, he was appointed the head of 1 of the 11 French departments of the SD, basing himself in Bordeaux. From here, Hagen instituted measures to deport Jews to their death. He once more worked with Eichmann, who was by now head of RSHA-Amt IV B4 (Jews and Clearances). On October 24, 1941, in an internment camp at Souges, northwestern France, Hagen was directly responsible for the execution by hanging of 50 hostages, having drawn up a death list specifically for this purpose. Then, in December 1941, Hagen set up a concentration camp for the Jews of the Mérignac region on the southern Atlantic coast.

On May 5, 1942, Hagen was appointed to the position of political assistant of Carl Oberg, who commanded the SS and police forces in France. He was deputized by Oberg to oversee anti-Jewish matters, while at the same time remaining active in other security activities under the leadership of SS-Obersturmburführer Helmut Knochen. Hagen then organized raids in Paris to deport Jews. A fluent speaker of French, he communicated the exact meaning of German demands to members of the Vichy regime, and in this way, Hagen took a leading role in working to suppress the resistance movement and at the same time organizing the transfer of workers and deportation of Jews from France.

On July 2, 1942, Hagen took part in a meeting that included the secretary-general of the French police, René Bousquet, who agreed to seize and hand over to the Germans for deportation 40,000 foreign Jews living in France. Hagen made an agreement with Vichy prime minister Pierre Laval that the latter, if asked what was happening to the Jews, would answer that Jews transferred from unoccupied France to the occupied zone were being transported to the Generalgouvernement in Poland. By August 1943, Hagen was demanding from Bousquet that Jews be denied French nationality as a means of easing their deportation.

In September 1944, Hagen was transferred to Carinthia in southern Austria and given command of an Einsatzkommando (special action squad) for engaging in antipartisan activities on the Yugoslav border.

He remained here until the end of the war, when he was arrested by British forces on May 13, 1945, and imprisoned in Carinthia’s capital, Klagenfurt. Shunted from place to place (including Italy and British prisons in Lower Saxony and Hamburg), he was handed by the British to the French occupation forces in November 1946. The investigation over the following year established Hagen’s responsibility for the deportation of Jews as a member of the SD in France. It was not until March 18, 1955, however, that Hagen was finally convicted for having been instrumental in the deportation of the Jews from France and condemned to lifelong forced labor by a military court in Paris.

However, under the terms of a treaty signed at Paris between the Federal Republic of Germany and the three Western powers (France, Britain, and the United States) on October 23, 1954, the remaining restrictions on German law regarding the prosecution of National Socialist crimes were abolished. This led to some categories of war criminals, such as Hagen, effectively receiving amnesties from any further prosecution because they could not be tried and punished for the same crime twice. Secure in the knowledge that he would be safe provided he did not leave Germany or go to France, Hagen settled down to a life in the corporate world.

In July 1978, the German State Prosecutor’s Office brought an action against Hagen and two other leading former Nazis, Kurt Lischka and Ernst Heinrichsohn, in Cologne. Over the next 15 months, the court learned that Hagen not only knew about the Nazi program to exterminate the Jews but was, in fact, a central figure in its implementation and was heavily involved in the deportation of Jews from France for a lengthy period. It was concluded that during his period in command, some 70 transports with 70,790 Jews were sent to the concentration camps in the East, of which at least 35,000 were killed in the gas chambers. On February 11, 1980, the Cologne Regional Court announced its verdict, and he was sentenced to 12 years imprisonment, to be served at the Hamm prison, in the Ruhr.

Released after only serving four years of his sentence, Hagen retired to private life. In 1997, he lived in a senior citizens’ home near Warstein, in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, and he died on August 7, 1999, in nearby Rüthen.

Wilhelm Harster was an SS-Gruppenführer and Holocaust perpetrator. He served as chief of security and police forces in the German-occupied Netherlands from 1940 to 1944 and in Italy from 1944 to 1945.

Harster was born on July 21, 1904, at Kelheim, Bavaria. His father was a lawyer and police officer. Harster attended grammar school in Munich, and in 1920, aged 16, he became a member of the Freikorps Bund Oberland. Harster joined the Reichswehr (the Germany army under the Weimar Republic) and remained a reservist after his training.

He took his law degree from the University of Munich in 1927, and in 1929, he joined the Stuttgart police force. Soon, he moved on to the political police.

On May 1, 1933, only three months after Adolf Hitler’s accession to office, Harster joined the NSDAP. In November 1933, he became a member of the SS, and in October 1935, the SD, eventually rising to Gruppenführer.

From March 31, 1938, to June 1, 1940, Harster led the State Police Regional Office in Innsbruck. As a Gestapo chief, he participated in the planning and executing the Kristallnacht pogrom there in November 1938.

In June 1940, after the onset of war the previous September, Harster was recalled to active duty and served from July 1940 in a machine-gun company. On July 19, 1940, only weeks after the German invasion of the Netherlands on May 10, 1940, he was posted there as commander of the SD, where he served until August 1944.

In 1941, Harster gave permission for “sharpened interrogation” (a euphemism for torture) of communist prisoners. This permission came after discussions with his Gestapo counterpart at the RSHA in Berlin, SS-Gruppenführer Heinrich Müller. It was initially not allowed for other prisoners, but in 1942, the sharpened interrogation process was extended. It was said that the screams of those being tortured could be heard coming from Harster’s office.

In early May 1943, in a letter to the German commanders of concentration camps in the Netherlands, Harster reported on talks he had with the RSHA in Berlin and spoke of recent instructions from Hanns-Albin Rauter, the highest SS and police leader in the occupied Netherlands, reporting directly to SS-Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler and the Nazi governor of the Netherlands, Arthur Seyss-Inquart. A clear statement regarding the extermination of the Dutch Jews, it was titled Endlösung der Judenfrage in Niederlanden (“Final Solution of the Jewish Question in the Netherlands”). As head of the SD in the Netherlands, Harster managed the mustering and transportation of the Dutch Jews and was ultimately implicated in the deaths of 104,000 Jews in the Holocaust.

After his role in the occupation of the Netherlands, Harster was redeployed as commander of the SD under General Karl Wolff in German-occupied parts of Italy from August 29, 1943. Here, he had contact with SS-Sturmbannführer Christian Wirth, inspector of the Aktion Reinhard death camps and former commandant of Bełżec.

Harster was captured by British forces on May 10, 1945, and between then and 1947, he was a prisoner of war. At the insistence of the Dutch, in 1947, Harster was extradited to the Netherlands to stand trial for war crimes committed while he headed the SD in Holland. He was imprisoned there until 1949. In 1949, Harster was convicted and given a 12-year prison term for his role in the persecution, deportation, and murder of the Dutch Jews and for negligence in failing to supervise the staff at the Amersfoort concentration camp.

He was released in 1953, having spent a total of eight years in prison. He returned to West Germany and took up a civil service position in Bavaria. By 1963, however, he was compelled to leave that job when his past deeds in the Netherlands came under more scrutiny, although he was permitted to keep his pension.

In 1967, German judicial authorities filed a new trial against Harster, in which he was charged with being coresponsible for the murder of thousands of Dutch Jews at Sobibór and Auschwitz. Convicted, he was given a 15-year jail sentence, with credit for time served. He was released in 1969.

Harster’s release caused an uproar in some circles, and the Dutch Auschwitz Committee formally petitioned the West German chancellor not to pardon Harster; the pardon, however, went forward in 1969. Harster died in Bavaria on December 25, 1991, aged 87.

Aribert Heim was an Austrian SS doctor, also known as “Dr. Death.” During World War II, he served at the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp, torturing and killing inmates by various methods, such as directly injecting toxic compounds into the hearts of his victims.

Aribert Ferdinand Heim was born on June 28, 1914, in Bad Radkersburg, Austria, into a middle-class family, and his father was a police officer. Heim was handsome, intelligent, and athletic and played professional ice hockey. He studied medicine in Graz and earned his doctorate in Vienna, graduating in 1940 aged 36.

Heim joined the Austrian Nazi Party in 1935, and after the Anschluss with Germany, he joined the SS. He volunteered for the Waffen-SS in the spring of 1940, rising to the rank of SS-Hauptsturmführer.

In October 1941, Heim was sent to Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp, near Linz, as a camp doctor, where he was known to inmates as “Dr. Death.” Between October and December 1941, he was stationed at Ebensee camp near Linz, where he carried out experiments on inmates. He was known for performing often-fatal operations and experiments, including injecting various solutions (gasoline, water, phenol, and poison) into Jewish prisoners’ hearts to see which induced a quicker death. He also operated on prisoners without anesthesia and removed organs from healthy inmates, leaving them to die on the operating table.

A former camp inmate gave evidence that an 18-year-old Jewish man came to the clinic with a foot inflammation. The 18-year-old was asked by Heim why he was so fit and replied that he had been a football player and swimmer. Instead of treating the prisoner’s foot, Heim placed him under anesthesia, cut him open, took out his kidneys, and castrated him. The young man was then decapitated. As the head apparently had perfect teeth, Heim boiled the flesh off the skull for use as a paperweight. Other survivors referred to Heim removing tattooed flesh from prisoners and using the skin to make seat coverings, which he gave to the commandant of the camp. Heim, who also served as a doctor at Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen, became notorious for collecting skulls.

In February 1942, Heim began serving under SS-Obergruppenführer Karl Maria Demelhuber in the Sixth SS Mountain Division Nord in Northern Finland, where he was an SS doctor in hospitals in the city of Oulu.

Heim was captured by U.S. soldiers on March 15, 1945, and sent to a prisoner-of-war camp. He was released and avoided immediate prosecution due to the omission of his time at Mauthausen from his American-held file in Germany. Following his release, Heim married, set up practice as a civilian doctor working as a gynecologist in Baden-Baden and Bad Nauheim, and fathered two sons.

One late afternoon in 1962, Heim telephoned his home and was told that police were waiting there for him. Based on his previous experiences, he presumed that an international warrant for his arrest was to be served. He went immediately into hiding. Much later, Heim’s son Rüdiger revealed that Heim drove across France and Spain to Morocco, Libya, and finally to Egypt. Over time, Heim acquired a reputation as the most wanted Nazi still at large. There were sightings reported of him in Latin America, Europe, and Africa.

Heim lived for many years in Cairo, Egypt, aided by family members and lawyers in Germany, who channeled money to him. Eventually he converted to Islam at the Al-Azhar mosque and lived under the alias Tarek Hussein Farid. He was never made to answer for his crimes in life. He died in Egypt of intestinal cancer on August 10, 1992, aged 78, and was buried in a pauper’s grave in Cairo.

HEISSMEYER, AUGUST (1897–1979)

August Heissmeyer, a general in the Waffen-SS, was head of the Inspectorate of Concentration Camps and director of the elite training schools of SS youth. As such, he played a huge role both in developing the infrastructure for the Holocaust and in conditioning German youth for the role they would play in bringing it about.

Heissmeyer was born on January 11, 1897, in Gellersen, Lower Saxony. Upon finishing school, he joined the German army and served with distinction as a junior officer during World War I, in which he was decorated with the Iron Cross First Class. After the war, he went back to school but found it difficult to settle back to a civilian routine. Like many frustrated veterans unable to succeed economically, he was drawn to right-wing politics, and in 1923, he first encountered the National Socialist Party. He became an early convert to the Nazi cause when he joined the party in 1925.

At the start of 1926, Heissmeyer became a member of the SA, where he was an active and successful senior leader. This was followed by membership of the SS in January 1930. In 1932, he obtained a position at the SS-Amt, the central command office of the SS created in 1931. In 1933, this was renamed the SS-Oberführerbereichen and was given responsibility for all SS units across the country. This then became the SS Main Office (SS-Hauptamt, or SS-HA) on January 30, 1935, with Heissmeyer in command.

Heissmeyer was promoted to SS-Obergruppenführer on November 9, 1936. Accompanying this promotion was a move to another SS institution, the National Political Institutes of Education (Nationalpolitische Erziehungsanstalten, or NPEA). These bodies—secondary boarding schools commonly abbreviated by the name Napola (an abbreviation for Nationalpolitische Lehranstalt, or National Political Institution of Teaching)—had as their mission the “education of national socialists, efficient in body and soul for service to the people and the state.”

Being elite schools, they were separate from the regular education system and regulated by a highly selective intake that accepted only the “worthiest” Aryan candidates. Those admitted were meant to become Germany’s future leaders and had to operate in a highly competitive, strictly militaristic environment featuring a politically charged curriculum based on physical strength, ideological indoctrination, and racialized programs. By the time war broke out in September 1939, the Napolas were essentially preparatory schools for entry into the Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS. Two of Heissmeyer’s own sons attended Napolas administered by their father.

Heissmeyer went further once war broke out. In 1939, he was appointed SS-Oberabschnittsleiter “Ost” (senior section leader east), and in 1940, he was further promoted as higher SS and police leader (Höherer SS und Polizeiführer, or SS-HSSPF) for the Spree area, with command of police forces in the region covering Berlin-Brandenburg. Considering that he had a responsibility for the Napola students’ military training, he set up his own section, the Dienststelle SS-Obergruppenführer Heissmeyer, to enhance the wartime chances of the young men in his care.

In 1940, Heissmeyer took over the Inspectorate of Concentration Camps from the outgoing inspector, Theodor Eicke, who had assumed command of a frontline SS division when the war broke out. Through his command of the SS-Totenkopfverbände, Heissmeyer effectively ran the concentration camp network across Germany and occupied Europe. He remained in charge until May 1942, a crucial time in the Holocaust during which the mass murder of Jews began in earnest. He left the position when a new inspector of concentration camps, SS-Gruppenführer Richard Glücks, was appointed.

On November 14, 1944, as the Reich began to collapse, Heissmeyer was promoted to SS-Oberstgruppenführer (general of the Waffen-SS)—the highest military rank available in the SS. Many SS men were given Waffen-SS commissions at this time so that if they were captured in combat, they would be treated according to the rules of war and not shot out of hand. Heissmeyer’s was far from being a paper commission, however; in April 1945, he was given command of a combat unit, Kampfgruppe Heissmeyer, and ordered to defend the Spandau airfield outside Berlin with a scratch division comprised of Volkssturm (home guard detachments established on the direct order of Adolf Hitler, comprising males aged between 16 and 60 years) and boys from the Hitler Youth.

With the final collapse of Germany, Heissmeyer and his wife, Gertrud Scholtz-Klink (leader of the National Socialist Women’s League, or NS-Frauenschaft), fled Berlin. Captured in the summer of 1945 and imprisoned in a Soviet prisoner-of-war camp near Magdeburg, they managed to escape soon after. In October 1945, a haven was provided for them by Princess Pauline of Württemberg, who, as director of the German Red Cross for the Rhineland, Hesse, Nassau, and Westphalia, had known Scholtz-Klink during the war. Princess Pauline arranged for the couple to live quietly in the village of Bebenhausen, where they spent the next three years under the alias of Heinrich and Maria Stuckebrock.

On February 29, 1948, Heissmeyer was captured by French authorities near Tübingen. Held for trial the following month, he served 18 months in prison before being released in 1949. In 1950, his case was reopened, and he was forced to appear before a denazification court. His sentence was reevaluated, and he was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment. After his release, he went to live in Schwäbisch Hall, Württemburg, where he became a director of the local Coca-Cola bottling plant. He died on January 16, 1979, five days after his 82nd birthday.

August Heissmeyer is not to be confused with his nephew, Kurt Heissmeyer, who was also an SS officer. A physician involved in medical experimentation on concentration camp inmates, he rose to prominence owing personal connections—in particular, through his uncle August and a friend, the SS general Oswald Pohl. In 1959, after living for many years as a successful medical practitioner in East Germany, Kurt Heissmeyer was identified and put on trial. In 1966, he was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. He died on August 29, 1967, aged 61.

Kurt Heissmeyer was an SS physician involved in medical experimentation on concentration camp inmates, including children.

He was born on December 26, 1905, in Lamspringe, Lower Saxony. His father was a physician, and his mother was a pastor’s daughter; together, his parents ran an authoritarian family home. His uncle was SS-Obergruppenführer August Heissmeyer; his aunt, married to August Heissmeyer, was Gertrud Schloss-Klink, the head of the Nazi Women’s League (NS-Frauenschaft). At university in Marburg, Heissmeyer joined the antisemitic Arminia fraternity.

Heissmeyer was licensed to practice medicine in 1933 and began specialist training in Freiburg before moving to the famous Davos-Clavadel clinic in Switzerland. Heissmeyer then became a resident at the Auguste-Victoria Hospital in Berlin. In 1937, he joined the Nazi Party. Building on his new party links, he became senior physician at Hohenlychen, a prestigious SS convalescent health spa at Uckermark, 70 miles north of Berlin, in 1938. Later he was elevated to assistant director. In this role, Heissmeyer fraternized with politicians and SS leaders from Berlin, including members of the administration of nearby Ravensbrück concentration camp.

Heissmeyer advanced his career by undertaking original research and publishing his scientific findings. In 1943, he wrote a paper entitled “Principles of Present and Future Problems of TB Sanatoriums.” His thesis, which, unknown to him, had first been proposed and disproved by Austrian researchers A. and H. Kutschera-Aichbergen, was that the injection of live tuberculosis bacilli into subjects would act as a vaccine. He also claimed that Jews, as Untermenschen (subhumans), have less resistance to tuberculosis than racially superior patients and that, due to their inherent weakness, Jewish subjects would be more useful for his research.

In spring 1944, a meeting was held at Hohenlychen between Heissmeyer and others, including Leonardo Conti, Karl Gebhardt, and Ernst Grawitz. Conti was the chief physician of the SS, Gebhardt was the medical director of Hohenlychen, and Grawitz was the state secretary for health in the Ministry of the Interior and, as head of the SS health services, also responsible for medical experiments on prisoners. At the meeting, Heissmeyer proposed his experiment seeking a cure for tuberculosis, in which his subjects would be Jewish concentration camp prisoners. After the meeting, Gebhardt asked Conti if Heissmeyer could use prisoners from Ravensbrück. Conti and Grawitz both agreed, with the only other permission needed from SS-Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler. Through Heissmeyer’s personal Nazi connections (his uncle, SS General August Heissmeyer, and his close acquaintance, SS General Oswald Pohl), Himmler’s permission was obtained. The experiments were to take place, however, at the Neuengamme concentration camp near Hamburg rather than at Ravensbrück.

Heissmeyer initially experimented on adult prisoners. By November 1944, he had observed that the condition of all “his” inmates had worsened following subcutaneous tubercle inoculation. The medical records from only 32 adult experiments have been preserved, but it is believed that Heissmeyer experimented on over 100 individuals.

Undaunted, Heissmeyer was anxious to complete the second phase of his research. He ordered 20 children with the intention of immunizing them against tuberculosis. He wanted Jewish children, it was said, because they represented an inferior and weaker race. Thus, in 1944, Heissmeyer had 20 Jewish children, 10 boys and 10 girls all between the ages of 5 and 12, transferred from Auschwitz to Neuengamme. His theory was that injections of living tuberculosis bacteria would grant their recipients immunity to the disease.

As Heissmeyer began his experiments on the children, Allied forces were crossing the Rhine. With a worsening of the children’s condition, he thought it would be valuable to see how the axillary glands of the children had reacted to the bacteria and ordered a Czech inmate surgeon to perform lymph-node dissections. Heissmeyer removed the children’s lymph glands and then began injecting the bacteria into the children’s lungs and bloodstreams.

The children grew weaker and were confined to their barracks. Heissmeyer did not know what to do with the 20 sick and dying Jewish children and sought Oswald Pohl’s advice. In March 1945, while the U.S. Third Army advanced into Germany, Pohl and Rudolph Hoess, the Auschwitz commandant, visited Neuengamme. It was Hoess who decided the children’s fate.

The Hamburg SS had taken over a bombed-out school, converted into a satellite camp of Neuengamme, at number 92/94 Bullenhuser Damm, two years earlier. The children were taken to this place. On April 20, 1945, when the British were less than three miles from the camp, the 20 children, along with the children’s 2 French physicians and 2 Dutch caretakers, were murdered by being hanged on hooks in the basement at Bullenhuser Damm.

On April 21, 1945, Heissmeyer fled Hohenlychen in civilian clothing and returned to Thuringia, where he worked in his father’s medical practice. He eventually settled in Magdeburg in postwar East Germany, where, for the next 18 years, he enjoyed a successful practice as the director of the only private TB clinic in East Germany. Heissmeyer’s practice was so large that he was able to purchase homes for each of his three children, and he was recognized as one of Magdeburg’s outstanding citizens.

Heissmeyer would have continued leading a prosperous life if, in 1959, the West German magazine Stern had not published an article deploring the omission of Nazi crimes from the curricula of German schoolchildren and referring specifically to the murders of the children at Bullenhuser Damm. A retired economist from Nuremberg began researching this murder and identified Heissmeyer’s role. Four years later, after verification of his identity, Heissmeyer was arrested by the East German General Prosecutor’s Office, charged with crimes against humanity, and imprisoned in Berlin. He initially denied the accusations but eventually led investigators to a box he had buried in the garden of his house in Hohenlychen, which contained documents and photographs relating to his experiments on children.

Heissmeyer’s trial began on June 21, 1966. Found guilty, he was sentenced to life imprisonment. At his trial he stated, “I did not think that inmates of a camp had full value as human beings.” When asked why he did not use guinea pigs, he responded, “For me there was no basic difference between human beings and guinea pigs.” He then corrected himself: “Jews and guinea pigs.” Heissmeyer was unrepentant to the very end. Fourteen months after being sentenced, on August 29, 1967, he died of a heart attack.

Gottlieb Hering was an SS commander who served in Aktion T-4 before becoming the last commandant of Bełżec extermination camp during Aktion Reinhard. He was also responsible for liquidating the Jewish labor camp at Poniatowa.

Hering was born on June 2, 1887, in Warmbronn, near Leonberg, Baden-Württenberg. After leaving school, he worked as an agricultural laborer on local farms, before being conscripted into the German army in 1915. He fought with a machine-gun regiment on the Western Front and was awarded the Iron Cross First Class.

In December 1918, released from the army, Hering joined the police service and served at Göppingen, Württemberg. Later, Hering worked in the Stuttgart criminal investigation division (Kripo), where he met Christian Wirth. Hering rose to the level of Kriminalinspector. He retained his position after the ascent to office of the Nazis, and between December 1939 and December 1940, he served in a team of Kripo officers in occupied Poland, specifically Gdynia (renamed Gotenhafen by the Nazis), where ethnic Germans were being resettled on the Baltic coast.

From late 1940, Hering had a range of roles in the Aktion T-4 program. As part of this, in 1941, he served at Bernberg in the registry office and then later in the registry at Hadamar euthanasia center. He then worked at Sonnenstein euthanasia center as an assistant supervisor and became the office manager at the Hartheim Castle euthanasia center.

After Aktion T-4 was suspended, Hering was posted briefly to the SD in Prague. In July 1942, he transferred to Bełżec death camp, reporting to Christian Wirth. One month later, he was promoted to commandant of Bełżec when Wirth moved on to become chief inspector of Aktion Reinhard. Within the overall program, the task of Bełżec was to destroy the Jewish communities of Eastern Poland, specifically Warsaw, Lublin, Kraków, and Lvov. SS-Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler was so impressed by Hering’s management that he promoted him to SS-Hauptsturmführer. Toward the end of the operation, the mass graves at Bełżec were opened and the corpses incinerated, while the gas chambers and other buildings were destroyed. The site was plowed over, trees were planted, and peaceful-looking farmhouses were constructed.

After Belźec ceased functioning in March 1943, Hering became commandant of the Jewish labor camp at Poniatowa. On November 3 to 4, 1943, German police killed the remaining Jews at Poniatowa during Aktion Erntefest (Operation Harvest Festival).

On October 14 to 15, 1943, prisoners at Sobibór rose in rebellion, killing several guards and making a mass escape. Within five days, SS-Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler ordered Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger to carry out Aktion Erntefest, which included the liquidation of Sobibór. Krüger delegated this task to Jakob Sporrenberg, the newly appointed HSSPF for Lublin. Other elements of the Aktion were carried out simultaneously in three camps—Poniatowa, Trawniki, and Majdanek—to prevent rumors transferring from one camp to another.

In late October 1943, the Jews at Poniatowa were told to dig two deep trenches, 95 meters long, 2 meters wide, and 1.5 meters deep, as defenses against air attacks. On November 3, 1943, the camp was surrounded by a police unit, which had been directed to murder all the Jews. They were taken to the trenches and shot. Some resisted by not coming out of their barracks, so the barracks were set on fire; all of those remaining inside were burned alive. About 150 Jews were left to clean the area and cremate the corpses. Fifty Jews who hid during the massacre joined them. Two days later, these 200 Jews were shot because they refused to cremate the corpses. In their place, 120 Jews were brought in from other camps to carry out this work.

In September 1943, after the Italian armistice, the port city of Trieste was seized by Wehrmacht troops. Here, at Risiera di San Sabba, the Germans built the lone Italian concentration camp with a crematorium, which operated from April 4, 1944. About 5,000 South Slavs, Italian anti-fascists, and Jews died at San Sabba, while thousands more transited there before transfer to other concentration camps.

In 1944, after Aktion Erntefest, Hering went to Trieste, where he again replaced Christian Wirth—this time as chief of Sonderkommando R1, after Wirth was killed by partisans. In Trieste, he joined fellow SS men from Aktion Reinhard, including Odilo Globocnik and those under his command, many of whom had been known to Hering for a long time already.

On May 1, 1945, Yugoslav partisans conquered most of Trieste. The German garrison refused to surrender to anyone other than New Zealanders, as Yugoslavs were reputed to shoot German prisoners. The Second New Zealand Division, under General Bernard Freyberg, arrived in Trieste on May 2, 1945, and the German forces surrendered that evening. They were immediately turned over to the Yugoslav forces.

On October 9, 1945, Gottlieb Hering died in mysterious circumstances (possibly suicide) at St. Catherine’s Hospital in Stetten im Remstal, near Kernen, Germany.

HEYDRICH, REINHARD (1904–1942)

Reinhard Heydrich was a high-ranking German Nazi official and one of the main architects of the Holocaust. An SS general, he headed the Reich Main Security Office, the SS and police agency most directly concerned with implementing the Nazi plan to murder the Jews of Europe.

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich was born in Halle, near Leipzig, Germany, on March 7, 1904, to a cultured Catholic musical family. His father, a Wagnerian opera singer, founded the Halle Conservatory of Music, and his mother was a skilled pianist. Heydrich was bullied at school because he had a high-pitched voice and was teased that he had Jewish blood (his grandmother had married for a second time after the birth of Heydrich’s father, to a man with a Jewish-sounding name). There was strong discipline in the home, where Heydrich was beaten, but he grew up driven to excel at academics, music (violin), athletics (fencing), horsemanship, and sailing.

The German defeat in World War I brought social chaos, inflation, and economic ruin to most German families, including Heydrich’s. Consequently, at the age of 16, he joined one of the many Freikorps groups that arose around the country—right-wing, antisemitic organizations of ex-soldiers involved in violently opposing communists on the streets. He desired to join the group in order to overcome the many persistent (though false) rumors regarding his Jewish ancestry. Heydrich believed that the German army was not defeated militarily in the war but was “stabbed in the back” and brought down by the German home front collapsing.

In March 1922, aged 18, Heydrich sought the free education, adventure, and prestige of a naval career, but this ended suddenly in 1931, when he became engaged to his future wife, Lina von Osten, and put aside another girlfriend who was from a prominent naval family. The girl’s father made an official complaint, and after proceedings before a court of honor, Heydrich was immediately discharged from the service.

That same year, Heydrich joined the Nazi Party and became active in the SA in Hamburg. Heinrich Himmler noted Heydrich’s managerial abilities and Aryan appearance and appointed him as the founding head of the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), the SS intelligence body tasked with locating and overcoming resistance to the Nazi Party through arrests, deportations, and murders. An SS-Brigadeführer by 1933, Heydrich built the SD into a powerful operation. Both Adolf Hitler and Himmler quickly became aware of the rumors of Heydrich’s Jewish blood spread by Heydrich’s enemies in the Nazi Party, and because of these rumors, Heydrich developed an immense hostility toward Jews.

In January 1933, following the Nazi seizure of power, Heydrich and Himmler administered the mass arrests of communists, trade unionists, Catholic politicians, and other opponents. An unused munitions factory at Dachau, near Munich, quickly became a concentration camp for political prisoners. By April 1934, Himmler took control of the new Secret State Police (Geheime Staatspolizei, or Gestapo), with Heydrich, his second in command, running the organization.

Two months later, in June 1934, Himmler and Heydrich, along with Hermann Göring, successfully plotted the downfall of powerful SA chief Ernst Röhm by spreading false rumors that Röhm and his 4 million SA storm troopers intended to seize control of the Reich and carry out a new revolution. In the purge, known as the Night of the Long Knives, the SA leadership was liquidated. Feared even within party ranks for his ruthlessness and known as the “Blond Beast,” Heydrich thereafter helped create the Nazi police state.

Heydrich also prompted Soviet leader Joseph Stalin into conducting a purge of top Red Army generals in 1937, by supplying evidence to Soviet secret agents of a possible military coup. Within Germany, Heydrich took part in bringing down two powerful conservative German generals who had opposed Hitler’s long-range war plans, announced in November 1937. War Minister Werner von Blomberg and the commander in chief of the army, Werner von Fritsch, were framed by unfounded character attacks; they were forced out, eliminating their influence. Following their dismissal, Hitler took over as army commander in chief.

Following the Nazi annexation of Austria in March 1938, the SS rounded up anti-Nazis and Jews. Heydrich established the Gestapo Office of Jewish Emigration, headed by Austrian native Adolf Eichmann; it became the sole office permitting Jews to leave Austria, and it took their assets in return for safe passage. Almost 100,000 Austrian Jews left, many of whom had handed over all their wealth to the SS. A similar office was set up in Berlin. Heydrich also helped organize the Kristallnacht, the pogrom targeting Jews throughout Germany and Austria on November 9 to 10, 1938.

Following the invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, Heydrich took charge of the RSHA (Reich Main Security Office). On Heydrich’s orders, Jews not shot outright were forced into overcrowded, walled-in ghettos in Warsaw, Kraków, and Łódź. By mid-1941, half a million Polish Jews had died from starvation and disease.

Heydrich established the Einsatzgruppen, killing squads charged with executing Jews and members of opposition groups, in German-controlled Poland and later the Soviet Union. After the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, he sent four Einsatzgruppen, marked A, B, C, and D, into the Soviet Union with orders to politically “pacify” the occupied areas by search and execution measures. All communists taken into custody were shot, along with suspected partisans, saboteurs, and anyone considered to be a security threat. The Einsatzgruppen followed the German army deep into Soviet territories and the Ukraine, aided by volunteer units of ethnic Germans who lived in Poland as well as volunteers from Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, and Ukraine.

On July 31, 1941, on Hitler’s order, Hermann Göring ordered Heydrich to put together the administrative material and financial measures necessary to carry out “the desired final solution of the Jewish question.” On January 20, 1942, Heydrich convened the Wannsee Conference in Berlin with 15 top Nazi bureaucrats to coordinate the Final Solution, under which the Nazis would eliminate all the Jews of Europe, an estimated 11 million people. To replace emigration, the conference’s alternative proposal was “deportation to the East,” a euphemistic solution approved by Hitler. This referred to mass deportations of Jews to ghettos in Poland and then on to the planned extermination complexes at Bełżec, Sobibór, and Treblinka. The plan forced the Jews to form Jewish Councils (Judenräte) who kept lists of names and assets, thereby partly organizing, administering, and financing the Final Solution themselves. By mid-1942, mass gassing of Jews using Zyklon B (hydrogen cyanide) began at Auschwitz in occupied Poland.

In September 1941, while still retaining his other duties, Hitler appointed Heydrich as deputy Reich protector of Bohemia and Moravia. His headquarters were in Prague. Shortly after, Heydrich created a ghetto for Jews at Theresienstadt. Although he offered incentives to Czech workers for food and privileges if they filled Nazi production quotas and displayed loyalty to the Reich, Heydrich’s agents cracked down on the Czech resistance movement. Heydrich would travel between Germany and his headquarters in Prague in an open-top green Mercedes without an armed escort in order to underscore how far he had intimidated and pacified the Czechs.

On May 27, 1942, against the expressed wishes of the local population who feared reprisals, British-trained Czech commandos ambushed Heydrich’s car, seriously wounding him. He died a few days later, on June 4, 1942. In retaliation, Hitler ordered the murder of thousands of Jews; he also wanted to kill 10,000 Czech political prisoners, but Himmler persuaded him that the Czechs were needed to supply Germany’s industrial needs. Nonetheless, more than 13,000 Czechs were arrested, and 5,000 were murdered in reprisals. False information led the Nazis to believe that the assassins were hiding in Lidice, a village near Prague; they also found a radio resistance transmitter in Ležáky. The Germans took revenge on Lidice by killing all 199 men in the town, arresting the 195 women and sending them to Ravensbrück concentration camp, and taking the 95 children, 8 of whom were given to German families. Lidice was demolished on June 9, 1942, and the ruins bulldozed. In Ležáky, all adults were murdered; the children disappeared, except for two who were handed over to Nazi families, and the town was razed.

Heydrich’s funeral in Berlin was remembered as the largest of its kind in Nazi Germany.

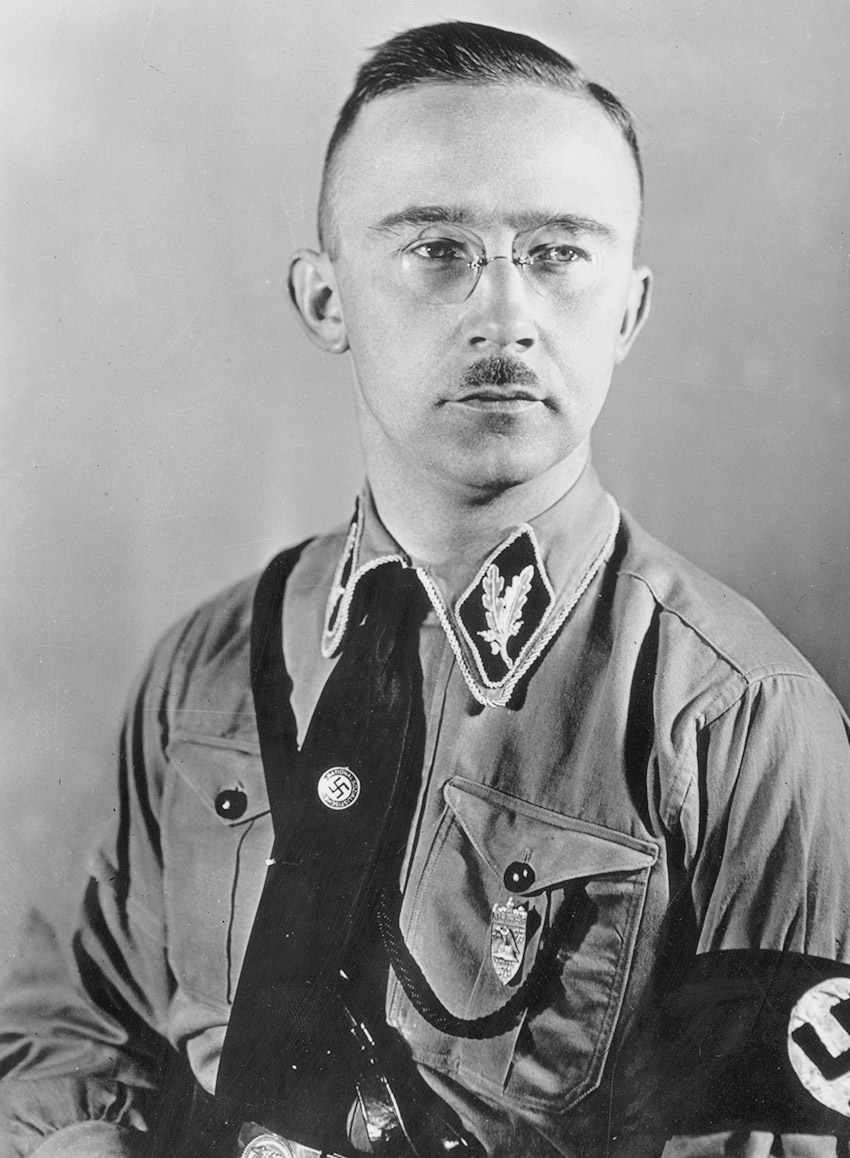

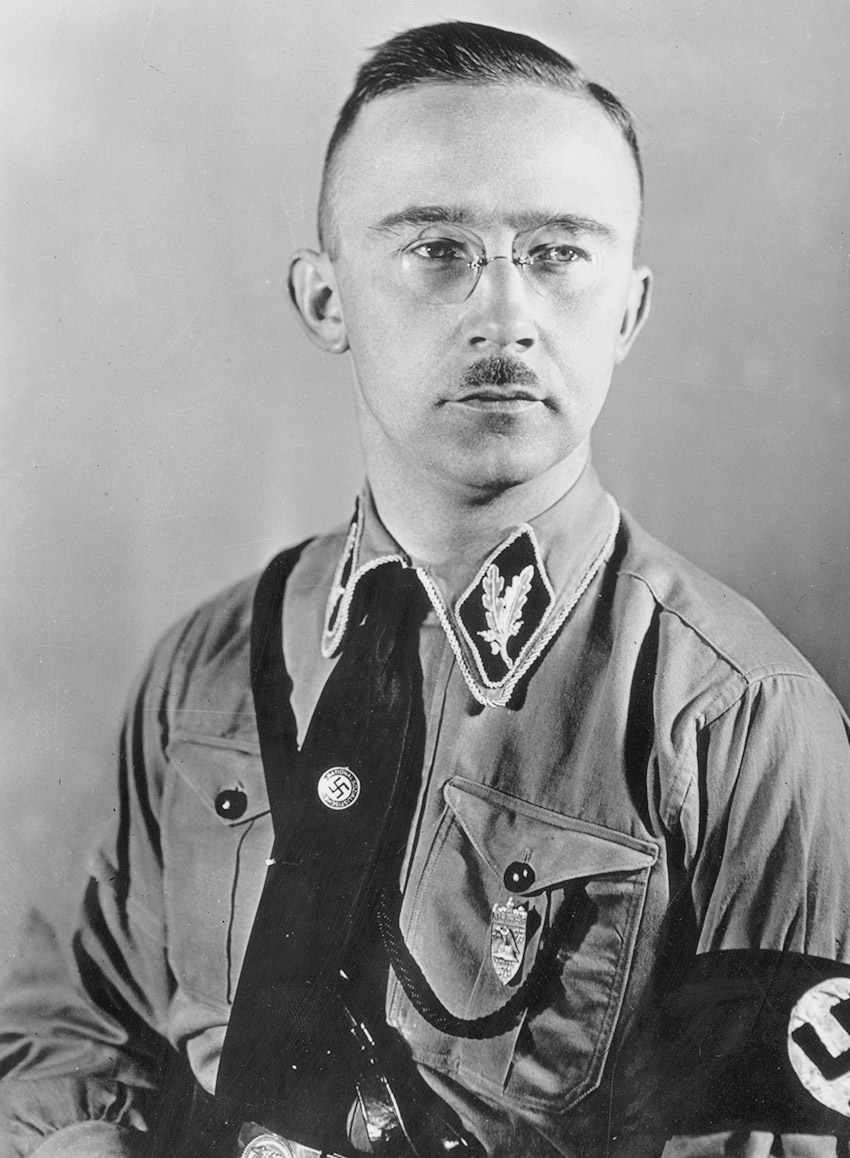

Heinrich Himmler, a leading member of the NSDAP and a key official in the government of Adolf Hitler, was head of the entire Nazi police force, including SD and the Gestapo; minister of the interior, and commander of the Waffen-SS and the Home Army. As the Reich leader of the Schutzstaffel (SS), Himmler administered the death camps in the East and oversaw the mass murder of Jews and other peoples during the Holocaust.

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler was born in Munich, Germany, on October 7, 1900, to devout Catholic, middle-class parents: Joseph, a teacher, and Anna Maria. He was named after his godfather, Prince Heinrich of Bavaria, whom his father had taught. In 1913, Himmler’s family moved to Landshut, about 40 miles northeast of Munich, where his father became assistant principal of the local high school. An intelligent and studious boy, Himmler struggled to overcome a sickly disposition. Awkward in social situations, he compensated by reading racist German writers who condemned what they identified as a strong Jewish influence in Germany. The young Himmler was interested in dueling and current events, and in 1915, he began training with the Landshut Cadet Corps.

Taking an emergency high school diploma, in 1917, he applied to the navy as a trainee officer but was rejected because he wore glasses. He then enlisted with the reserve battalion of the 11th Bavarian Regiment in December 1917. His father’s connections ensured Himmler’s acceptance for officer training, which he began on January 1, 1918. Himmler was still in training when the war ended with Germany’s defeat in November 1918, denying him the opportunity to see combat or complete his officer training. Upon his discharge on December 18, 1918, he formalized his high school qualification and graduated in July 1919.

In April 1919, Himmler joined the Freikorps Lauterbach and came to Munich under Kurt Eisner to fight in street battles against the communists. His application to join the army was rejected. In October 1919, following a brief farm apprenticeship and an illness, Himmler studied agronomy from 1919 to 1922 at the Munich Technical High School. Here, he joined numerous clubs, including the German Society for Breeding Studies. He completed his diploma in 1922.

After Foreign Minister Walther Rathenau’s murder on June 24, 1922, Himmler turned further toward the radical right. Disappointed by his inability to find a military career and unable to afford his doctoral studies, he took a low-paying job as a laboratory assistant and salesman in a fertilizer company, remaining until September 1923. After a few months, he resigned to join Ernst Röhm’s paramilitary Imperial War Reich Flag Society. Soon after this, he joined the National Socialist Party and took part in Hitler’s failed Beer Hall Putsch on November 8 to 9, 1923. While Himmler was not charged for his role in the putsch because of insufficient evidence, he was able to find work as an agronomist and had to move back to his parents’ home.

Arguably the second most powerful man in Germany after Hitler, Heinrich Himmler was head of the entire Nazi police force, including the SS, the SD, and the Gestapo. As head of the SS, Himmler administered the death camps in the East and oversaw the mass murder of Jews as well as countless other victims during the Holocaust. At the end of the war he was captured by British forces but never stood trial for his crimes; on May 23, 1945, he swallowed a hidden cyanide capsule and committed suicide. (Keystone/Getty Images)

These failures made him more irritable and aggressive; he alienated himself from friends and family, and during 1923 to 1924, he abandoned Catholicism. Occult Germanic mythology became his religion, instead, while politically the NSDAP appealed to him because its positions reflected his own views. While he was not swept up by Hitler’s charisma, Himmler read his works and admired him greatly.

From mid-1924, Himmler worked as secretary and personal assistant to party secretary Gregor Strasser, whom Hitler appointed party propaganda head in 1926. Himmler traveled the whole of Bavaria, giving speeches and handing out writings. From late 1924, Strasser placed him in charge of the NSDAP’s offices in Lower Bavaria; Himmler was responsible for bringing in new members when the party was refounded in February 1925. In 1926, Himmler was appointed as deputy gauleiter of Oberbayern and Swabia. From then until 1930, he was also acting propaganda leader of the NSDAP.

Himmler also made a reputation for himself in the party as a speaker and organizer. His speeches emphasized race consciousness, the need for German expansion and settlements, and long-standing opposition toward Germany’s enemies: “Jewish” capital, Marxism (i.e., socialism, communism, and anarchism), liberal democracy, and the Slavic peoples. His background in agriculture placed Himmler comfortably in a party that stressed the myth of “blood and soil,” and he was obsessed with notions of selective breeding and racial perfection. In 1927, Himmler was appointed deputy Reichsführer of the Schutzstaffel (SS), a post he held until his appointment as SS-Reichsführer on January 6, 1929.

On July 3, 1928, Himmler married Margarete Boden, who bore him a daughter, Gudrun, on August 8, 1929. They set up a poultry farm at Waldtrudering, near Munich, but Himmler was not a successful farmer. After Gudrun’s birth, he left both his wife and the farm.

On January 6, 1929, Himmler was appointed to head Hitler’s personal bodyguard, the black-shirted SS, at that time a small body of 280 men. The SS was subservient to the SA and had two major functions: to serve as bodyguards for Hitler and other Nazi leaders and to market subscriptions for the Nazi Party newspaper, the Völkischer Beobachter. From this foundation, Himmler developed the elite corps of the Nazi Party. By 1930, the SS had grown to 2,700 men, and Himmler had managed to make it into an organization independent from the SA. Himmler was elected to the Reichstag for the constituency of Weser-Ems.

In April 1931, Himmler used his SS troops to crush a revolt by the Berlin SA against Hitler’s leadership. The suppression of the SA mutiny showed the SS to be an internal party police organization showing unconditional loyalty to Hitler through its motto “My honor is loyalty.”

In 1931, Himmler commissioned his close associate, Reinhard Heydrich, to create the Security Service SD, which, in August 1934, became the main intelligence organization of the party. It kept watch on Hitler’s internal opponents and gathered intelligence on other political parties as well as local and federal government officials. On January 25, 1932, Himmler was appointed the security chief of the NSDAP headquarters in Munich, the so-called Brown House.

By January 1933, when the Nazis seized power, the SS numbered more than 52,000 officers, and Himmler had taken charge of two key responsibilities for Germany: internal security and guardianship over racial purity. In March 1933, Himmler was appointed head of the Munich police and took over responsibility for the structure and management of the concentration camp at Dachau. On April 1, 1933, the Bavarian state government was dismissed, and Himmler became the political police commander; by January 1934, he extended his control of the police force in all German states except for Prussia and Schaumburg-Lippe. On April 20, 1934, because of growing tension between the Nazi leadership and the SA, Hermann Göring appointed Himmler as inspector of the Secret State Police (Gestapo). The joining of the Gestapo with Heydrich’s SD resulted in Himmler administering tight control over the whole system, adding also to the size and influence of the SS.

Himmler and Heydrich were instrumental in convincing Hitler to purge the leadership of the SA. As a result, Himmler and the SS were the main participants in the June 1934 purge that became known as the Night of the Long Knives. Himmler was personally involved in the arrest and murder of SA leaders and Hitler’s political opponents in Berlin. By July 1934, Himmler, as SS-Reichsführer, reported directly to Hitler, making him one of the most powerful men in Germany. With total control over the concentration camps, the SS had sole responsibility for their construction and management throughout Germany, while the Gestapo was able to act against supposed opponents of the regime without reference to the judicial system.

In February 1938, Himmler used the SD to force Werner von Fritsch and Werner von Blomberg to resign from their army leadership posts, elevating Hitler to complete control over Germany’s military. In August 1938, against the opposition of the Wehrmacht, Hitler gave a military role to the SS, which later formed the Waffen-SS; although assigned to the Wehrmacht, these units remained under Himmler’s control as SS-Reichsführer. This overrode the arms monopoly of the army and gave Himmler authority over an independent armed force.

Shortly after World War II broke out on September 3, 1939, the administration of the Gestapo, the Criminal Police, and the SD merged to create the Reichsicherheitshauptamt (RSHA), operating under the SS. Heydrich became head of the RSHA, reporting directly to Himmler. Then on October 7, 1939, Himmler was appointed Reichskommissar for the consolidation of German nationality, with responsibility for displacing and oppressing the local population in the occupied territories in accordance with Nazi racial ideology.

Upon the occupation of Poland, the SS assumed responsibility to purge the enemies of the German Reich in the occupied territories. The Einsatzgruppen, special squads under Heydrich’s direct command, organized the expulsion, persecution, and murder of hundreds of thousands of Poles and Jews. Himmler described the massive eradication policy as a “heavy duty” for his subordinates.

In 1941, following Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, Hitler transferred Himmler to police security in the areas occupied by the Wehrmacht, and with this, he became the main contributor to the Final Solution of the Jewish Question, the deportation and murder of the European Jews. People considered to be “subhuman” from all over Eastern Europe were next incarcerated into camps and ghettos to prevent organized resistance and to permit German population expansion into the occupied territories. Later, those Jews who were not summarily shot were herded into ghettos and then later sent to death camps, where they were gassed and burned in crematoria. Himmler himself often visited execution sites and the camps and was the person most active in turning Hitler’s violent hatred toward Jews and other peoples into an extermination program. His brilliant organizational skills had awful consequences for the Jews. It was Himmler who ensured that the deportations took place and that the camps all ran on business lines so that they paid for themselves and made profits where possible.

In 1942, Himmler was given control to impose Nazi criminal law over all Russians, Poles, and Jews in the occupied territories as well as power to exploit the large number of prisoners of war as slave labor for the war economy. Himmler laid down and implemented the Generalplan Ost, which used force to expel and relocate millions of Poles, Czechs, Ukrainians, and White Ruthenians, deemed to be “sub-human,” to Siberia—at the same time, moving ethnic Germans into newly conquered territories.

In January 1943, after the assassination of Heydrich the previous summer, Ernst Kaltenbrunner became head of the SD and the RSHA, replacing Himmler, who had been in charge of management before June 1942. Meanwhile, Himmler continued to increase his power and accumulate more offices. On August 25, 1943, Hitler appointed Himmler as minister of the interior, and on October 4, 1943, in a three-hour speech in Posen to top-ranking SS officers, he spoke openly about the “extermination” of the Jews.

In February 1944, at Himmler’s insistence, Hitler dismissed Admiral Wilhelm Canaris as chief of Germany’s military intelligence service, the Abwehr. The Abwehr’s functions were taken over by the RSHA, and areas previously the responsibility of the Abwehr were divided between Gestapo and the RSHA.

On July 20, 1944, an attempt was made on Hitler’s life by a group of army officers. Himmler himself oversaw the arrest, prosecution, and execution of those responsible. This unsuccessful assassination brought Himmler further power and the entry into the Wehrmacht, as Hitler appointed him, on July 21, 1944, to be the successor of General Friedrich Fromm as a leading commander of the army. He also became commander in chief of Army Group Vistula.

On December 2, 1944, Himmler took over Army Group Oberrhein in order to build up a new defensive line, but by January and February 1945, it became obvious that he lacked the military skills necessary for a commander in chief. To avoid further responsibility, Himmler escaped to an SS hospital and was replaced in March 1945.

By the spring of 1945, Himmler’s loyalty to Hitler was beginning to waver, as Germany was clearly losing the war. Having made desperate attempts to conceal and destroy evidence of his monstrous crimes, Himmler sought to arrange a German surrender to the Western Allies; hoping to avoid capture by the Red Army, he counted on the anticommunist sentiment of the West to negotiate an anti-Soviet alliance that would include Germany.

In April 28, 1945, when Hitler learned that Himmler, as his successor and possible mediator, had made unauthorized peace overtures to the Western Allies, Himmler was dismissed from all offices and party membership and Hitler prepared an arrest warrant against him. The notorious former SS leader was now unwelcomed in the new German government. He attempted to escape the ruined country through British lines under a false name. He was captured, however, and on May 23, 1945, while in British custody at Lüneburg, he committed suicide by swallowing a cyanide capsule.

Fritz Hippler was a German filmmaker who ran the film department in the Propaganda Ministry of the Third Reich, under Joseph Goebbels. He was born on August 17, 1909 and brought up in Berlin. The son of a minor official who died in France during World War I, he was only 10 years of age when the Treaty of Versailles was signed, but during his teenage years, he developed an intense hatred toward the Weimar Republic. In 1927, he joined the Nazi Party and became a member of the SA. When he was old enough, he became a law student at universities in Heidelberg and Berlin, and by 1934, he had earned his PhD at the University of Heidelberg.

In 1932, he became a Nazi Party district speaker and was promptly expelled from the University of Berlin for inciting violence. On April 19, 1933, however, the newly installed National Socialist education minister, Bernhard Rust, overthrew all existing disciplinary actions against students associated with the Nazi Party, enabling Hippler’s return. He then became the district and high school group leader for Berlin-Brandenburg in the National Socialist German Students’ League. On May 22, 1933, following Goebbels’s lead on May 10, Hippler gave a speech to his fellow students that precipitated a march from the student house to Opera Square with a collection of banned books, which were then publicly burned.

In 1936, Hippler became an assistant to the artist, photographer, and film director Hans Weidemann. In this capacity, he worked on the production of newsreels and learned the techniques behind documentary filmmaking. His work was undertaken through the Reich Propaganda Ministry, and with it came a promotion in 1938 to the rank of SS-Hauptsturmführer. In January 1939, he took over Weidemann’s position, meaning that he now worked directly for Goebbels. By August 1939, Hippler had been promoted to head the film department at the ministry. Among his tasks he determined which foreign films would be allowed on German screens and what parts of them would be cut.

He also produced and directed movies. In 1940, Hippler directed Der Feldzug in Poland (The Campaign in Poland), a propaganda film demonstrating the superiority of German arms in the first phase of World War II from September 1939 onward.

His most famous—indeed, infamous—creative work was undoubtedly another feature-length film from 1940: Der Ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew), arguably one of the most offensive antisemitic propaganda movies ever made. The film consists of documentary footage combined with materials filmed shortly after the Nazi occupation of Poland. Hippler shot footage in the Jewish ghettos of Łódź, Warsaw, Kraków, and Lublin, the only such footage, as it turned out, shot specifically for the film. The rest of the film consisted of stills and archival footage from other feature films—footage that the film presented as if it was an additional documentary film. The film itself covered four essential tropes: “degenerate” Jewish life as seen in the Polish ghettos; the nature of Jewish political, cultural, and social values; Jewish religious ceremonies, instruction, worship, and ritual slaughter; and Adolf Hitler as the savior of Germany from the Jews.

Even though the Nazis had not themselves yet decided on mass annihilation as the means to destroy Europe’s Jews, the intention of the film was to prepare the German population for the coming Holocaust. However, the movie did not have the desired impact on the German public, owing to the fact that a major motion picture, Jud Süss (Veit Harlan, 1940), had already appeared to rapturous acclaim employing top box-office stars and building on captivating period drama. By contrast, Der Ewige Jude was a documentary based on limited original footage, still images, and archival film clips. Unlike Jud Süss, therefore, which was a great commercial success, Der Ewige Jude was a failure at the box office. As a propaganda film, it was shown more for training purposes to troops on the Eastern Front and SS members than it was in cinemas, although a few foreign-language voice-overs were made, and the film was exported to countries occupied by Germany.

Hippler, for his part, was honored by Adolf Hitler, and his career was made. In October 1942, he was appointed director in charge of Reich filmmaking, with responsibility for all control, supervision, and direction of German movies. He now became second only to Goebbels, and by 1943, he was promoted to SS-Obersturmbannführer.

Such a career trajectory, though impressive, generated resentment in some quarters—no less than from Goebbels himself. The Reichsminister had long kept a watching brief on Hippler, whom he saw as sometimes impertinent, often immature, disorganized, and too fond of alcohol. In this latter area, Goebbels had a point. Hippler indeed suffered from an addiction to alcohol, and it was for this that Goebbels finally dismissed him in June 1943. Hippler was stripped of his SS rank, and a trumped-up accusation was brought against him that he had denied having a Jewish great-grandmother. Hippler was sent to an infantry-replacement battalion and underwent mountain infantry training. Released from active duty, he was then given the task of shooting newsreel footage as cameraman until February 1945. At the end of the war, he was taken by the British as a prisoner of war.

In 1946, he was tried for directing Der Ewige Jude and sentenced to two years in prison. Staging a comeback after his release, he collaborated on documentary movies under another name. In a 1981 memoir, he claimed that Goebbels was the real creator of Der Ewige Jude, having directed large parts of it himself and giving Hippler the credit. Later, he stated that he regretted being listed as the director of the movie because it unfairly resulted in his treatment after the war. In his opinion, he had nothing to do with the killing of Jews and only shot some footage for a film that Goebbels himself then put together. Moreover, he claimed that at the time he had little knowledge of the Nazis’ murderous policies toward the Jews and was not aware of the Holocaust as it was taking place. He said that if he could, he would “annul” everything about the film, which had caused him such personal difficulties in his subsequent life.

Fritz Hippler lived in Berchtesgaden, Bavaria, until his death on May 22, 2002, aged 92.

August Hirt was a physician with an interest in anatomy. During World War II, he carried out mustard-gas experiments on inmates at the Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp and also arranged for the murder of 86 Auschwitz inmates so that their bodies could be used as part of his research on skeletons for his collection of “Judeo-Bolshevik” skulls as specimens at the Institute of Anatomy in Strasbourg.

Hirt was born on April 28, 1898, in Mannheim, Baden, to a Swiss businessman father. In 1914, aged 16 and still a high school student, he volunteered to fight for Germany in World War I. In October 1916, he suffered a bullet wound in his upper jaw; he was awarded an Iron Cross and returned home to Mannheim in 1917.

Hirt studied medicine at the University of Heidelberg, and in 1922, he took out his doctorate in medicine with a thesis investigating the nervous system of dinosaurs. He worked at the Anatomical Institute in Heidelberg, and in 1925, he started teaching at Heidelberg University. By 1930, he was a professor there.

Hirt had taken out German citizenship in 1921, giving him dual Swiss and German nationality. On April 1, 1933, he joined the SS; he joined the Nazi Party on May 1, 1937, and within two months, he had attained the rank of SS-Hauptsturmführer. From March 1, 1942, he was a staff member at the Rasse- und Siedlungshauptamt der SS (SS Race and Settlement Main Office, or RuSHA), the organization in charge of ensuring “racial and ideological purity” among members of the SS. In 1944, he attained the rank of SS-Sturmbannführer.

The Ahnenerbe was a Nazi initiative dedicated to researching the history, culture, and anthropology of the Aryan race. Its aim was to establish that Nordic peoples once ruled the earth. The Institut für Wehrwissenschaftliche Zweckforschung (Institute for Military Scientific Research), which performed wide-ranging human-subject medical research, became part of the Ahnenerbe during World War II. The institute was managed by Wolfram Sievers, who had founded the organization on the orders of SS-Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler. Himmler appointed Sievers as institute director with two divisions, one headed by Sigmund Rascher and the other by August Hirt.

Hirt was regard as an expert on the deadly mustard-gas toxin. Fearing that the Allies might use it against Germany, Himmler tasked Hirt to find an antidote. Prior to World War II, Hirt had carried out mustard gas experiments with rats, but with the onset of war, he sought to repeat these experiments on humans in the Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp, near Strasbourg. Chosen inmates were subjected to mustard gas through a drip in the arm; within a few hours, they experienced burns over their bodies and suffered excruciating pain. Some inmates went blind; others died. The corpses were then dissected to remove and study the damaged organs.

In 1942, Hirt—now head of the department of anatomy at the Reich University in Strasbourg, working under the aegis of the Ahnenerbe—proposed to collect skulls of “Judeo-Bolsheviks” who embodied the “disgusting but characteristic subhuman” as part of his research on race. Himmler approved the proposal; he wanted the RuSHA to review all children of mixed marriages and their progeny for three or four generations. Descendants with “Jewish features” could be sterilized, if not murdered. To enable this, the SS needed a clearer understanding of Jewish “race traits.”

Hirt thus sought to create a museum of “subhumans,” in which the so-called Jewish traits would be exhibited. Himmler allowed Hirt to choose any prisoners from Auschwitz he needed. In August 1943, Wolfram Sievers, together with Hirt and anthropologists Bruno Beger and Hans Fleischhacker, selected 115 individuals at Auschwitz: 79 Jewish men, 30 Jewish women, 2 Poles, and 4 “Asians” whose nationality was not determined. These were the people who would be used to create a specimen collection of Jews. Of those selected, 89 people (60 men and 29 women) were sent to Natzweiler-Struthof on July 30, 1943. Three men died en route. The victims were fed to improve their appearance for the casts that would be made of their bodies. Divided into four groups, they were successively gassed in the small-scale gas chamber at Natzweiler-Struthof by Josef Kramer during August 1943. Their corpses were sent to Hirt at Reich University in Strasbourg, where their skeletons were prepared as an anthropological display.

Hirt stored the bodies in alcohol-filled tanks. In September 1944, the rapid approach of French troops led to the project being abandoned and to Himmler ordering the destruction of all traces of the collection. Part of Hirt’s skull collection is said to have been moved to Mittersill Castle, in Salzburg, Austria, in the fall of 1944. On liberating Strasbourg, the Allies found corpses and the partial remains preserved in formalin of 86 bodies. The corpses were buried on October 23, 1945, before being transferred in 1951 to the Jewish cemetery of Strasbourg-Cronenbourg. The names of the victims were not known.

Hirt escaped from Strasbourg in September 1944 and hid in Tübingen, southern Germany. He was tried in absentia for war crimes at the Military War Crimes Trial at Metz on December 23, 1953. Unknown to the tribunal, however, Hirt had committed suicide on June 2, 1945, aged 47, at Schluchsee, Baden-Württemberg.

Josef Hirtreiter was an SS officer who worked at Treblinka during the Aktion Reinhard phase of the Holocaust in Poland. In 1951, he was the first SS man brought to trial for war crimes committed at Treblinka.

Josef Hirtreiter was born on February 1, 1909, in Bruchsal, near Karlsruhe. After completing elementary school, he trained as a locksmith but failed the final examination. He then worked as an unskilled construction worker and bricklayer. On August 1, 1932, he became a member of the SA and the Nazi Party.

In October 1940, after the invasion of Poland, Hirtreiter was assigned to the Hadamar euthanasia center, an extermination facility of Aktion T-4. He worked in the kitchen and the office and was also involved in cremating corpses.

In summer 1942, he was called up to join the Wehrmacht; he was in the army for only a short time before being sent back to Hadamar. Shortly after his return, Hirtreiter was assigned to Aktion Reinhard and transferred to Berlin; from there, Christian Wirth sent him to the camp complex at Lublin in occupied Poland. On August 20, 1942, along with seven other T-4 veterans, Hirtreiter arrived at Treblinka. There, he acquired the rank of SS-Scharführer. He served at Treblinka II, in the receiving area, between October 1942 and October 1943. He became known by the nickname “Sepp,” a diminutive of Josef. Because of his cruelty, he soon became the terror of Jewish prisoners and became notorious as a murderer of infants and small children.

In October 1943, Hirtreiter moved on to Sobibór to assist with the liquidation of the camp. Then, after the closure of Treblinka in October 1943, he was ordered to Italy, where he joined a police unit for antipartisan cleansing operations.

After the Aktion Reinhard camps were liquidated, most operatives were sent to Trieste in Italy, tasked with assisting with the suppression of partisan activities. Franz Stangl, Hirtreiter’s camp commander, suggested that while he had been told he was being sent to Trieste to set up the Risiera di San Sabba killing center there, senior Nazi politicians realized that the staff and commanders of Aktion Reinhard could incriminate their superiors. Consequently, operatives were sent to dangerous areas where some of them, such as Wirth, were killed.

Hirtreiter was arrested by the Allies in July 1946 for having served at Hadamar and jailed in Darmstadt. He was released due to a lack of incriminating evidence that he was complicit in murdering mentally ill people.

He was then rearrested in 1951, after testimony from former Treblinka prisoner Szyja (Sawek or Jeszajahu) Warszawski, who survived, wounded, in a burial pit and slipped away under the cover of night. Hirtreiter was charged in March 1951 at Frankfurt am Main and convicted for killing children, many aged one or two, during the unloading of the transports. He was known to grab them by their feet and smash their heads against the walls of boxcars. He was also found guilty of beating two prisoners (because money had been found on them) until they were unconscious, hanging them by their feet, and finally killing them with a shot to the head.

Hirtreiter was sentenced to life imprisonment on March 3, 1951. He was the first of the Treblinka extermination camp SS officers tried over a decade later at Düsseldorf. Released from prison in 1977 due to illness, he died six months later, on November 27, 1978, in a home for the elderly in Frankfurt.

Adolf Hitler was a German politician who was the founder and head of the Nazi Party, chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and führer (leader) of the Nazi State from 1934 to 1945. In his efforts to implement a racial policy in which Germans and Aryans became the master race over Europe, he led his Third Reich into actions, which resulted in the deaths of 35 million people.

Adolf Hitler, the fourth of six children, was born on April 20, 1889, at Braunau-am-Inn, Austria, the son of Alois Hitler, a German customs clerk, and his third wife Klara, an indulgent, hardworking Austrian. He was a slow learner, did poorly in school, and was frequently beaten by his strict, authoritarian father. His mother tried to shield him, but he was only freed from his father’s cruelty, at the age of 14, by his father’s death. Hitler dropped out of high school when 16 years old. An aspiring artist, he went to Vienna in October 1907 but twice failed to be accepted into the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts. His mother died from cancer in 1908.

Bitter at his rejection by the academy, he spent five difficult years in Vienna, where he learned politics from the inflammatory speeches of the populist Christian Socialist mayor, Karl Lueger, and picked up Lueger’s stereotyped, obsessive antisemitism with its concerns about “purity of blood.” This shaped the hatred of Jews, Marxists, liberals, and the Hapsburg rulers that he retained throughout his life. He lived a hand-to-mouth existence, working occasional odd jobs and selling his sketches through taverns, where he also gave political speeches to customers. Although Austrian, Hitler became a German nationalist, and in 1913, he moved to Bavaria in the German Empire.

From wild racial theories in Vienna, Hitler took the concept of the “Eternal Jew” as the symbol and cause of all chaos, corruption, and decadence in culture, politics, and the economy. He viewed the press, prostitution, syphilis, capitalism, Marxism, democracy, and pacifism as means in which “the Jew” conspired to undermine the German nation and the purity of the creative Aryan race.

With the outbreak of World War I, Hitler enlisted in the 16th Bavarian Infantry Regiment of the German army, in which he served until 1919. He was assigned a role as a regimental messenger runner but also saw combat; during those years, he received four decorations for bravery, including the prestigious Iron Cross First Class. In Flanders in 1918, he was temporarily blinded in a gas attack; he spent several months recuperating and was promoted from private to corporal, receiving the Iron Cross Second Class. When the war ended, he was posted to an intelligence unit in the army and assigned to spy on certain radical political parties. One of these was the German Workers’ Party. Hitler was finally mustered out of the German army in 1919.

Adolf Hitler became the leader of the Nazi Party in 1921 and was chancellor of Germany between 1933 and 1945. He served as undisputed Führer (“leader”) of the Nazi State from 1934 onward. As dictator, he initiated World War II by invading Poland in September 1939 and then, implementing an extreme policy of racial exclusivism, presided over a regime that perpetrated the Holocaust of Europe’s Jews. Hitler thereby became one of the most notorious mass murderers in history. (Photos.com)

The June 1919 Treaty of Versailles imposed on defeated Germany severe economic penalties, causing great hardship for the German people. On September 16, 1919, the thoroughly disenchanted Hitler joined the same German Workers’ Party (DAP), which had originally been his surveillance target. The DAP was the creation of Dietrich Eckart, who spread doctrines of mysticism and antisemitism, and Hitler soon managed to convert the party into the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP), of which he became the leader in 1921.

In 1920, Hitler’s intelligence handler, Munich-based Colonel Karl Haushofer, adopted the swastika insignia, and Hitler himself designed the Nazi Party banner, using the swastika symbol and placing it in a white circle on a red background. In 1921, Haushofer founded the paramilitary storm troopers (Sturmabteiling, or SA), composed of German veterans of World War I and undercover military intelligence officers. These storm troopers helped Hitler to organize the failed coup, the infamous Beer Hall Putsch, against the Bavarian government in Munich.

The attempted coup took place on November 8 to 9, 1923, and proceeded with help from SA leader Ernst Röhm, Hermann Göring, and General Erich von Ludendorff. Hitler and his coconspirators stormed the Bürgerbräukeller, a Munich beer hall, where members of the Bavarian state government were gathered. The coup was crushed by police and military units; Hitler was convicted of treason, sentenced to five years in jail, and imprisoned in Landsberg Prison. He only served nine months before a general amnesty was declared, but while there, he dictated to his deputy, Rudolf Hess, the first volume of his autobiography and political manifesto, Mein Kampf (My Struggle). In it, he openly displayed his antisemitism, as well as Germany’s urgent need for Lebensraum (living space), or territorial expansion in the East. The book was not taken seriously, however, and its warning signs went unheeded.

Released in 1924, Hitler worked to build up the Nazi Party. He generated support by attacking the Treaty of Versailles, while promoting pan-Germanism, antisemitism, and anticommunism—all of which proceeded from propaganda that denounced international capitalism and communism as being part of the Jewish conspiracy.

After his failed putsch, Hitler resolved to overthrow the established Weimar Republic by working within the system, and his demagoguery, as well as general economic unrest, led to increasing Nazi representation at all levels of government via elections held during the 1920s. The Great Depression, which began in 1929, gave Hitler’s goals a tremendous boost, as Germans turned to him for leadership in Germany’s national economic crisis. Hitler was provided with a personal bodyguard unit named the Schutzstaffel, or SS, and the Nazis began to gain considerable support in Germany through their network of army and war veterans. By 1932, the Nazis had become the largest party in the Reichstag, although they never achieved a majority of votes or seats.

Hitler ruled the NSDAP through an autocratic style, asserting the leader principle (Führerprinzip), which relied on total obedience of all subordinates to their superiors. He viewed leadership as a pyramid, with himself—the infallible leader—at the peak, demanding total loyalty of all party members to himself. Party roles were filled through appointment by those of higher rank, who demanded unquestioning obedience to the will of the leader. Hitler’s leadership style was to give contradictory orders to his subordinates and to foster distrust, competition, and infighting, which consolidated and maximized his own power.

The electorate responded to Hitler’s promises of jobs, security, and a greater Germany. In 1932, Hitler ran for the presidency against 84-year-old Paul von Hindenburg. Hitler came second in both rounds of the election, gaining more than 36 percent of the vote in the final count, and these results set Hitler up as a strong force in German politics. Hindenburg reluctantly agreed to appoint him as chancellor on January 30, 1933, in a coalition government with strong support from right-wing German industrialists and bankers, who saw in Hitler their bulwark against communism.