CHAPTER 9

Diet and Obesity

Nutritive Value of Food

In order to ascertain the customs and methods of persons of different stations in life regarding the purchase and use of their food a series of investigations are being conducted by the Department of Agriculture. These inquiries are of a distinctly practical character, and they are made with the co-operation of a number of experiment stations, colleges, and other organizations, as well as of private individuals, in different parts of the country. The general scope of the investigations includes the determination of the amounts and nutritive value of the food consumed by a given number of persons during a certain number of days, and the deducting of the quantities per man per day.

It is believed that such information, coupled with that derived from the study of the composition, digestibility, and nutritive value of food materials in common use on the one hand, and with that which comes from research into the laws of nutrition on the other hand, will gradually make it possible to judge what are the more common dietary errors and how improvements may be made to the advantage of health, purse, and home life. A variety of digestion experiments have already been made, and others are in progress, under Governmental supervision. Accounts of studies of dietaries of families, boarding houses, and clubs are from time to time made the subject of official reports.

How Experiments Are Made

In these studies account is taken of the amounts, composition, and cost of all food materials of nutritive value in the house at the beginning, purchased during and remaining at the end of each experiment, and of all the kitchen and table wastes. Such accessories as baking powder, essences, salt, condiments, tea, coffee, &c., although of interest from a pecuniary standpoint, are of no practical value as regards nutriments. The sum of the different food materials on hand at the beginning and those received during the experiment is taken, and from this sum the quantities remaining at the end are subtracted, thus giving the amount of each material actually used. From the amount thus obtained and the composition of each material, as shown by analysis, the amounts of the nutritive ingredients are estimated. From these are subtracted the amounts of nutrients in the waste, and thus the amounts of nutrients actually eaten are learned. In all of these experimental inquiries account is kept of the meals taken by the different members of the family and by visitors. The number of meals for one man, to which the total number of actual meals taken is equivalent, is estimated upon the basis of the potential energy. These energy equivalents are somewhat arbitrary, and it is acknowledged that they will require revision in the light of accumulating information.

Following is a table of estimated relative quantities of potential energy in nutrients required by persons of different classes:

| Man at moderate work | 1.0 |

| Woman at moderate work | .8 |

| Boy between 14 and 16, inclusive | .8 |

| Girl between 14 and 16, inclusive | .7 |

| Child between 10 and 13, inclusive | .6 |

| Child between 6 and 9, inclusive | .5 |

| Child between 2 and 5, inclusive | .4 |

| Child under 2 | .3 |

Where Studies Have Been Made

The dietary studies already made include a boarding house, a blacksmith’s family, a jeweler’s family, a chemist’s family, an infant nine months old, a college students’ eating club, a Swedish laborer’s family, a female college students’ club, farmer’s family, a camping party in Maine, a poor widow’s family, a man in the Adirondacks under treatment for consumption, and a mason’s family. As a general thing, the figures used for the percentages of nutrients in each food material are taken from the averages given for like food materials in Bulletin No. 28 of the Office of Experiment Stations of the Department of Agriculture. The figures in that bulletin represent the results of a compilation of analyses made previous to Jan. 1, 1895. In estimating the fuel values of the nutritive ingredients, the proteine and carbohydrates are assumed to contain 4.1 and the fats 9.3 calories of potential energy per gram. These correspond to 1,860 calories for one pound of proteine, or carbohydrates, and 4,220 calories for one pound of fats.

Fuel Values of Bacon, Turkey and Cod

Bacon has a very large percentage of fuel value. The latest official analysis shows that a portion of bacon, with the inedible parts discarded, contains 17.8 parts water, 9.8 parts of proteine, 68 parts fat, and 4.4 parts ash, and has a fuel value of 3,050 calories per pound. By the same analysis, the edible portion of a turkey is found to contain 55.5 parts water, 20.6 parts proteine, 22.9 parts fat, and 1 part ash, with a fuel value of 1,350 calories per pound. Codfish (edible portion) contains 82.0 parts water. 15.8 parts proteine, .4 part fat, and 1.2 parts ash, and has a fuel value of 310 calories per pound.

In each of the dietary studies reported the data regarding the kinds and amounts of food material, the persons by whom they were eaten, and the number of days and meals were sent to the Government Experiment Station at Middletown, Conn., where the necessary computations were made. For the sake of simplicity and convenience, the computed quantities for one man for ten days are given, instead of the actual quantities consumed, or the quantities for one man for one day. If the quantities were stated as actually consumed in the period of each dietary, it would not be easy to compare the quantities in different dietaries. By putting the quantities for all of the dietaries on one basis, however, the relative amounts of the different kinds of food materials, as meats, milk, bread, and the like in the different dietaries are readily compared. If the quantities were given per man per day, some would be too small for printing without the use of an inconvenient number of decimal places.

What a Laborer’s Family Ate

A fourteen days’ study was given to the dietary of a laborer’s family in Hartford, Conn. The family consisted of man and wife, three girls, aged respectively four, six, and eleven years; a boy, two and a half years old, and an infant. The father was a laborer in a coal yard, earning $8 per week. The mother had worked as a servant before her marriage and did her own cooking. The food materials bought by this family consisted of beef, veal, mutton, pork, salt codfish, eggs, butter, milk, rice, flour, rolled oats, bread, beans, sugar, potatoes, onions, and raisins. The consumption of food, calculated for one man ten days, was: 13.2 pounds of animal food, 9.6 pounds of cereals and sugars, 11.1 pounds of vegetables, and 2 pounds of fruit, a total of 34.1 pounds. This total quantity cost $1.53, and it contained 2.41 pounds of proteine, 2.24 pounds of fat, and 9.59 pounds of carbohydrates, the aggregate fuel value being 31,760 calories per pound. The following table shows the nutrients and potential energy in the food purchased, rejected, and eaten by this entire family during the period of fourteen days:

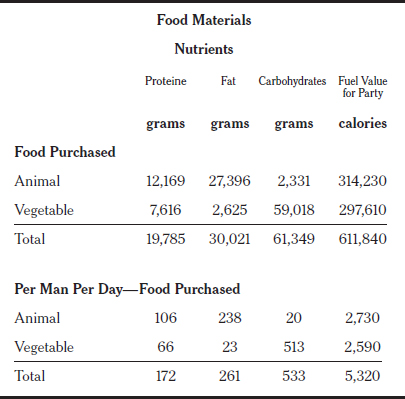

What a Camping Party Required

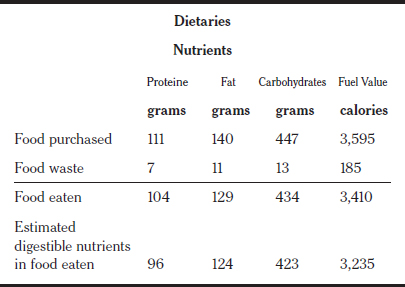

In the Summer of 1895, four young men, from nineteen to twenty-two years of age, spent some time canoeing and camping on the Allagash River, in Maine. As they took their journey leisurely, they may be considered as being engaged in light work. The whole time included in the dietary study of this party is estimated as equivalent to 115 days for one man. The following table shows the nutrients and potential energy in the food purchased, rejected, and eaten by this camping party:

The average of thirty-eight dietaries recorded by the Government officials make the following interesting showing:

Character of Sandow’s Food

About a year ago, during an engagement of Eugene Sandow, the “strong man,” in Washington, an attempt was made to determine the character and amount of the food he consumed. Mr. Sandow claims to be the strongest man in the world, and at the time of the investigation he had the appearance of being in perfect health. He did not then follow any prescribed diet, but ate whatever he desired, always being careful, as is his custom, to eat less than he craved. He always ate very slowly. He smoked a great deal and drank beer and other beverages. Below is the result of a study of Sandow’s dietary for one day:

It was noted that Sandow rejected all of the visible fat of the meat served him, and in his case it was shown that while the amount of carbo-hydrates and fat consumed did not differ very greatly from the standard for a man at muscular work, the amount of proteine (albumen) was very large. The fact that so much proteine was consumed by Sandow sustains the theory advanced by scientific experimenters that the energy which is used in the production of severe muscular labor is furnished by the combustion of proteine.

Official experiments regarding the digestibility of food by healthy men are now in progress. It has been demonstrated that 98 per cent of the proteine and 97 per cent of the fat in animal foods is readily digested; also that 85 per cent of the proteine and 90 per cent of the fat in cereals and sugars, and 80 per cent of the proteine and 90 per cent of the fat in vegetables and fruits is readily digested.

June 6, 1897

Insurance Study Finds Close Correlation Between Weights and Mortality Rates

By WILLIAM L. LAURENCE

The Society of Actuaries, most of whose members are in the field of life insurance, published last week a report on its twenty-year study of body build and blood pressure. The survey, described by the Institute of Life Insurance as “by far the most extensive statistical investigation ever undertaken in the health field,” is based on vital statistics provided by several million insured individuals.

The policy holders, studied over a period dating back to 1935, provide a picture of mortality in relation to weight and blood pressure for comparison with previous figures, some dating back to the turn of the century.

According to the institute, the findings “make obsolete” the figures on average weights now shown on weighing machines and used by physicians throughout the country. These figures are based on an actuarial study of thirty years ago.

The study of the variations in mortality according to weight included nearly 5,000,000 insured persons and covered a period of twenty years. In addition, the study covers mortality rates according to variation in blood pressure among nearly 4,000,000 insured individuals.

Women Weigh Less

Women were found to weigh less than they did a generation ago, while men tend to be heavier. The weights of women in their twenties average at least five pounds less than those of three to four decades ago, and, in fact, women of all ages now tip the scales several pounds less. This, it was stated, is partly due to lighter clothing (they were clothed when weighed) but reflects mainly the established vogue of slenderness.

In contrast, the average weights of short and medium-height men in their twenties and thirties are now five pounds higher. The increase in men’s weights at other ages and for tall men has been generally smaller.

Average weights for both men and women increase with age through the fifties. However, the pattern of the increase is different in the two sexes. Men start putting on weight in the twenties and level off in the forties, while women stay slim into the thirties and do not usually begin putting on weight until after the mid-thirties.

The study shows a correlation between overweight and higher mortality rates. Men weighing twenty pounds above the average have a 10 per cent higher mortality rate; those weighing 25 pounds above the average have an excess mortality of 25 per cent, while a weight of fifty pounds above the average is associated with a death rate as much as 50 to 70 per cent higher. Women were found to stand added weight better than men.

The study shows that overweight is accompanied by markedly increased mortality from diabetes and some digestive diseases, such as those of the gall bladder. With greater increases in weight, the death rate from heart disease rises sharply.

Below Average

In both sexes, the lowest mortality at ages over thirty is found among those 15 to 20 per cent below average weight. In the teens, a slightly above average weight shows a small advantage. Edward A. Lew, statistician for Metropolitan Life and chairman of the committee that made the study, commented that the data show the average American to be about twenty pounds overweight.

The study showed that reducing adds years to life. The mortality rate dropped to normal in a group that was overweight when insured but later got standard insurance by showing sustained weight reduction.

The most striking revelation was that even a small increase in blood pressure above the average, the level at which most physicians tell you not to worry, may significantly shorten the lifespan. Among men, the study showed, a systolic blood pressure (the pressure when the heart contracts) of 150 or a diastolic blood pressure (when the heart relaxes) of 100 are associated with excess mortality of 75 to 125 percent. Women were found to withstand high blood pressure much better than men.

The lowest mortality among both men and women was found among those with below average blood pressures.

Blood Pressure

Overweight in combination with elevated blood pressure is found to be a warning of increased danger. Where the two conditions occur together, the rise in death rate is much greater than is accounted for by the two conditions considered separately. Dr. John J. Hutchinson, Medical Director of the New York Life Insurance Company, said he could “offer no obvious explanation of the mechanism whereby moderate overweight in combination with blood pressure of only the slightest departure from the normal produces a mortality experience nearly twice the expected.”

Individuals with high blood pressure or overweight in combination with albumin in the urine are similarly subject to significantly higher mortality than that associated with each of these conditions alone. A history of two or more cases of early cardiovascular (heart and blood vessel) kidney disease in the family is also associated with markedly higher mortality, particularly from heart disease, the new data show.

October 25, 1959

Federal Heart Panel Asks Public to Eat Fewer Fats

By JANE E. BRODY

A national commission of medical experts recommended in a report released yesterday that Americans make “safe and reasonable” changes in their diets to lower blood cholesterol levels in the hope of stemming the current “epidemic” of heart disease.

At the same time, the commission urged the immediate adoption of a national policy committed to the primary prevention of premature atherosclerosis and its attendant cardiovascular diseases.

Of the 600,000 American deaths attributed to heart disease each year, 165,000 are “premature” deaths occurring in persons under the age of 65. Men are three times more likely than women to be the victims of premature coronary death.

The dietary changes recommended yesterday included a halving of the current average daily consumption of cholesterol and saturated fats and a substantial reduction in total fat intake.

To achieve this, the commission advised Americans to cut down on egg yolks, butter fat, fatty meats, organ meats, shellfish and fat-rich baked goods and candies and to substitute wherever possible products prepared with unsaturated fats. Most vegetable oils are unsaturated.

The commission’s recommendation was based on a large body of data gathered from both animals and man that suggest that changes in the typical fat-rich American diet can help prevent or at least delay cardiovascular diseases.

Noting that definitive evidence linking dietary fats and cholesterol to human heart disease is not available, the commission called for large-scale, long-term, Government sponsored studies to determine once and for all the effect that changes in diet and other factors may have on the nation’s slowly rising coronary mortality rate.

Such a study would involve perhaps 100,000 persons followed for five to 10 years at an estimated cost of $50 million to $100 million.

The commission said that it was recommending a change in diet despite the lack of definitive evidence because “the American public would probably have to wait at least 10 years for the results of these studies [and] at times urgent public health decisions must be made on the basis of incomplete evidence.”

Other “Risk Factors”

In addition to diet and its effect on blood fat levels, the commission singled out high blood pressure and cigarette smoking as the major “risk factors” leading to premature heart disease and coronary deaths. Accordingly, the report recommended an “orderly phasing out” of the cigarette industry with strict restraints on the sale and advertising of cigarettes and a major national effort to detect and treat victims of high blood pressure.

The commission, called the Intersociety Commission for Heart Disease Resources, consists of 115 leading American medical and nursing personnel. It was set up under the Regional Medical Programs, sponsored by the Federal Government, to formulate policy guidelines to prevent premature heart disease and improve care of coronary patients.

Under the chairmanship of Dr. Irving Wright, professor emeritus at Cornell University, and the direction of Dr. Donald T. Fredrickson, the commission will produce a series of reports in the coming months on other aspects of coronary care.

The current report, considered the commission’s major effort, was discussed at a news conference at the Biltmore Hotel here yesterday. The full report will be published in this month’s issue of the journal Circulation.

Dr. Fredrickson summarized the commission’s dietary recommendations as follows:

The current American diet, which draws about 40 per cent of its calories from fat, should be cut down to include no more than 35 per cent fats; the saturated fat level, currently at 16 to 20 percent, should be cut in half, and the cholesterol level, currently at 600 to 750 milligrams a day, should be no more than 300 milligrams daily.

Foods high in cholesterol include egg yolks and dairy and animal fats.

At the same time, Dr. Fredrickson said, intake of polyunsaturated fats (the oils of corn, peanuts, soybeans and the like), which currently averages 7 per cent of calories, should not exceed 10 per cent. The remaining dietary fats should come from monounsaturated fats like olive oil.

Change in Standards

According to Dr. Frederick H. Epstein, epidemiologist at the University of Michigan, such a dietary change “can lower serum cholesterol by 10 to 15 per cent.”

“At a conservative estimate,” he said, “such an effect on serum cholesterol might lower the incidence of coronary heart disease by as much as 30 per cent.”

To help Americans achieve this dietary change, the commission urged that Federal food standards be changed to permit the sale of processed meats and dairy products in which unsaturated fats substitute for saturated fats. Under current standards, for example, milk that has part or all of its butter fat replaced by vegetable oil must be called “imitation milk.”

The commission also called upon the Food and Drug Administration to change its labeling laws to permit manufacturers to list the exact fat contents of their products so that Americans would have a better idea of what they were eating in the way of fats and cholesterol.

Other risk factors that the commission linked to premature heart disease were diabetes, obesity, sedentary living, a family history of heart disease and possibly “psychological tensions.”

December 16, 1970

Atkins Diet: A “Revolution” That Has Medical Society Up in Arms

By JANE E. BRODY

The Medical Society of the County of New York yesterday denounced Dr. Robert C. Atkins’s “revolutionary” no-carbohydrate diet as “unscientific,” “unbalanced” and “potentially dangerous,” especially to persons prone to kidney disease, heart disease and gout.

At a news conference called by its Committee on Public Health, the society said that the side effects of the kind of diet Dr. Atkins promotes in his best-selling book may include weakness, apathy, dehydration, loss of calcium, nausea, lack of stamina and a tendency to fainting.

The Atkins diet is basically a high-protein, high-fat, no- to very-low-carbohydrate diet in which, it is claimed, the dieter can eat all he wants of the permitted foods and still lose weight.

The society’s criticisms, which echo those made last week by the Council of Foods and Nutrition of the American Medical Association, were generally denied by Dr. Atkins, who said that neither group had reviewed his yet-unpublished records nor studied a group of patients who had faithfully followed his diet.

The seven doctors who participated in yesterday’s news conference said that more serious effects of the diet might include kidney failure in persons with kidney disease, disturbances in normal heart rhythm, too much uric acid in the blood (a precursor to gout) and too much blood fats (a precursor to heart disease).

And if followed by pregnant women, as recommended in Dr. Atkins’s book, Dr. Karlis Adamsons of Mount Sinai Medical Center said that the diet could impair the intellectual development of the unborn child.

Below Normal Amount

The first week of the Atkins diet cuts out carbohydrates altogether. That means fruits, juices and nearly all vegetables as well as the traditional diet no-no’s— cake, ice cream, candy, etc.

As the diet progresses, the dieter is permitted to add tiny amounts of very-low-carbohydrate foods—some vegetables and fruits—but at most, the maintenance Atkins diet still contains only about one-sixth the amount of carbohydrates present in the ordinary American diet.

A variation on the old “calories don’t count” theme, the Atkins diet is designed to cause a condition called ketosis, which is at the heart of many of the medical society’s objections.

Ketosis is the presence of large amounts of chemicals called “ketone bodies” that spill over into the blood and urine as a result of the incomplete metabolism of fats.

Warns of Problems

Dr. Robert Kark, professor of medicine at Rush College of Medicine in Chicago, told the news conference that in otherwise normal healthy persons ketosis can cause nausea, vomiting, apathy, fatigue and low blood pressure, and in persons with kidney disease, it can produce kidney failure. Several participants said they had seen or heard of such symptoms developing in adherents to the Atkins diet.

Dr. Atkins, interviewed at his office here, said that “the scientific basis of the medical society’s allegations are in total disagreement with my findings, which are based on careful clinical observation of 10,000 obese subjects studied for nine years.”

He added that the A.M.A. had declined his invitation to look over his data. He said he is now tabulating the data in computer form for detailed analysis.

“I can tell you on the basis of a preliminary hand tabulation that renal [kidney] shutdown has never happened among my patients, and complaints of nausea, fatigue and apathy occur less often than on a balanced low-calorie diet—in fact, about one-tenth as often,” Dr. Atkins said.

Discusses Cholesterol

As to whether his diet will contribute further to the nation’s already out-of-hand epidemic of heart disease, Dr. Atkins said that on the average blood cholesterol and triglyceride levels fall in people following his diet, even though it contains large amount of cholesterol and saturated fats.

He said that about 8 or 9 per cent of Atkins dieters respond with rises in blood cholesterol and that these patients “may have an increased risk,” but that about 40 per cent experience “a significant reduction” in cholesterol levels.

With regard to pregnancy, Dr. Atkins now says that his diet “has not been tried sufficiently in pregnant women to recommend its use at this time.” Dr. Adamsons said that, all other things being equal, children have an I.Q. 10 points lower on the average if their mothers experienced ketosis during pregnancy.

It remains to be seen what the criticisms will mean to the hundred of thousands of Americans who are now following Dr. Atkins’s dietary regimen (his book, Dr. Atkins’ Diet Revolution, is a runaway best-seller with more than 600,000 copies sold within five months of publication).

Some Express Misgivings

Some of the Atkins faithful reported yesterday that they already feel a little nervous about continuing on the diet. But, as a 46-year-old 300-pounder said, “I ate more stupidly than this when I was not on the diet. At this point, I’m willing to take my chances about heart disease. After the way I’ve eaten all these years, anything is an improvement.”

The man said the “diet is the first he has ever tried—“and believe me, I’ve tried everything, including doctors’ diets with and without pills”—on which he could lose weight and not be hungry.

“For the first time in my life, I can turn things down without willpower, which I’ve never had,” he said, “And I feel great, psyched up, almost like I was taking amphetamines.”

He outlined a typical day’s diet: A cheese omelet with two eggs and a glass of seltzer for breakfast; two cheeseburgers without bread, a small wedge of lettuce with oil and vinegar and two glasses of water for lunch, a serving of broiled fish, and other wedge of lettuce and low-calorie gelatin pudding for dinner, and a couple of chunks of cheese for a bedtime snack.

“I Don’t Get Hungry”

When told that the reporter weighs one-third what he does and eats more than that, the man conceded that he was indeed consuming many fewer calories than he ordinarily did, but that “it’s easy to do it because I really don’t get hungry.”

The medical society panel questioned the long-run success of such a diet as Dr. Atkins proposes. It called such a diet “unbalanced.”

Dr. Roger Lerner of the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons said that “losing weight is a learning experience—the patient has to learn the caloric and nutritional values of foods. There are no panaceas. A low-calorie diet with a balance of protein, fat and carbohydrate is the most successful in the long run.”

Dr. Jules Hirsch of Rockefeller University, whose studies have shown that fat people have more and larger fat cells in their bodies than thin people, predicted that the Atkins diet fad would flourish and fade just like its dozens of predecessors, “among them the drinking man’s diet, the grapefruit diet, the hard-boiled egg diet, the Stillman diet, the Air Force diet—there are almost as many passé diets as there are calories in a piece of chocolate layer cake.”

Despite them all, Dr. Hirsch said, about a third of the nation continues to suffer from unwanted, excess body fat.

But it was Dr. Ethan Allan Sims, obesity expert from the University of Vermont Medical Center, who cited one of the most inhibiting aspects of the Atkins diet.

“It’s a Jet Set diet—poor people couldn’t afford to live on proteins and fats,” he said. “Besides America is already living off the top of the food chain—its resources couldn’t support the consumption of more animal proteins.”

March 14, 1973

Metabolism Found to Adjust for a Body’s Natural Weight

By GINA KOLATA

In a new study that helps explain one of the givens of obesity—that the body has a weight that it naturally gravitates to—researchers have found that all people, fat or thin, adjust their metabolism to maintain that weight.

The body burns calories more slowly than normal after weight is lost, and faster than normal when weight is gained, the study found. This means it is harder both to lose and, perhaps surprising to some, to gain weight than to maintain the same level. In the study, researchers found that in volunteers who gained weight, metabolism was speeded up by 10 percent to 15 percent, and in those who lost weight, metabolism was 10 percent to 15 percent slower than normal. The volunteers, both female and male, ranged in age from their 20s to their 40s, but the effect on metabolism was independent of age and sex.

The researchers also found that the way the body adjusts its metabolism is by making muscles more or less efficient in burning calories. Their findings mean that a 140-pound woman, for example, who has lost 15 pounds to achieve that weight will burn about 10 percent to 15 percent fewer calories when she exercises than a woman who maintains that weight effortlessly. Conversely, if a 140-pound woman gains 15 pounds, she will burn about 10 percent to 15 percent more calories when she exercises than a woman who had always weighed 155 pounds.

The study, conducted by researchers at Rockefeller University in an unusually rigorous manner, was published today in the New England Journal of Medicine. Dr. Jules Hirsch, physician in chief at Rockefeller and the senior author of the study, said the findings showed that obesity, rather than being an eating disorder, is “an eating order.” Obese people, he said, eat to maintain the weight that puts their energy metabolism precisely on target for their height and body composition.

One myth the study demolishes is that excessive dieting deranges the metabolism. The study showed equally perturbed metabolisms in those who gained and lost weight, whether they had ever dieted and whether they were fat or lean.

Another myth the study debunks is that obese people have unusually slow metabolisms. The only people in the study who showed sluggish metabolisms were those who were trying to maintain a body weight that was lower than their natural weight.

The researchers suggest that the best way to help dieters in the future might be to understand what makes the muscles more or less efficient with weight gain or loss, rather than focusing on diets and psychological counseling.

“I’d say this is a landmark investigation,” said Dr. Albert Stunkard, a psychiatrist and weight-loss expert at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. Calling the work “first rate,” he said the group’s data were so carefully gathered and the study so thorough that “what they are proposing is almost certainly right.”

Dr. William Ira Bennett, a psychiatrist at Cambridge Hospital in Cambridge, Mass., who wrote an editorial accompanying the paper, praised the work, saying “what it shows is very very interesting” particularly because it was done on humans, not laboratory animals on which so much of the work on obesity and metabolism has been done.

Weight control is an obsession for many Americans and a big business in this country, but Dr. Rudolph L. Leibel, an author of the study, said what was surprising was how little weight people actually gain. Data from the Framingham Heart Study, an ongoing study of more than 10,000 people in Massachusetts, showed that adults increased their weight, on average, by just 10 percent over 20 years.

For a man to gain 20 pounds over 30 years, he would have had to consume about 60,000 calories more than he needed, Dr. Leibel said. But, he pointed out, those extra 60,000 calories are a minuscule fraction of the 300 million the man had to consume just to maintain his weight. “It’s frightening how fine that control is,” Dr. Leibel said.

Most people find it easier to gain weight than to lose it. Although it is easy to eat just an extra 200 or so calories a day, resulting in added pounds, it is much harder to subtract 200 or so calories. “It’s painful; it hurts to be in negative energy balance,” Dr. Leibel said.

Dr. Leibel said he and his colleagues, Dr. Hirsch and Dr. Michael Rosenbaum, began their study because they wanted to understand why it was that the hardest part of dieting was keeping the weight off.

The group recruited 18 people who were obese and 23 who had never been overweight. They were required to live at the clinical center at Rockefeller while their diet and activities were carefully controlled.

For the first four to six weeks, the volunteers ate only a liquid diet that kept their weights absolutely stable. The researchers knew each subject’s energy intake and knew that their body weight was not changing, which meant that the subjects were expending the same amount of calories they were taking in.

Then the volunteers purposely gained weight by eating 5,000 to 6,000 additional calories a day until they were 10 percent above their normal weights. Gaining weight was difficult for everyone.

“Some people might imagine that an obese person, given free rein to eat as much as they want, would have a field day,” Dr. Leibel said. “But that was absolutely not the case. If anything, the obese subjects had a harder time gaining the extra 10 percent and were more uncomfortable with it.”

After the subjects had added 10 percent to their body weight, they were fed liquid formula for four to six weeks with enough calories to keep their weight stable. The researchers repeated the metabolic studies and found increased metabolism.

Then the volunteers lost weight, by consuming 800 calories a day. When they were 10 percent below their normal weights, the researchers maintained them there for four to six weeks with a liquid formula and repeated the metabolic studies, which this time showed a decreased metabolic rate.

The normal-weight volunteers, who were mostly students, received $40 a day for participating, Dr. Leibel said. The obese volunteers were not paid but were promised that at the end of the study, the researchers would keep them on a special diet at the clinical center until they no longer were fat. Some spent a year there after the end of the study, Dr. Leibel said. Most reduced to within 20 percent to 30 percent of the recommended weight for their height and build, and some got down to that weight, but none were able to maintain the weight loss. Inexorably, their weight crept up again.

“This tells you why the recidivism rate to obesity is so enormous,” Dr. Leibel said. “Even at a weight loss of 10 percent, the body starts to compensate.”

The investigators also studied what the body does to change its metabolism. They found that about 65 percent to 70 percent of calories burned each day are used to keep up the routine body functions—the pumping heart, the working kidneys, the metabolizing liver. About 10 percent to 15 percent are spent eating and assimilating food. And the rest, about 15 percent to 25 percent, are spent by the muscles’ exercising.

Now, Dr. Leibel said, “we need to figure out what the heck is going on in muscle.”

One possibility is that the muscle fibers themselves may change their composition slightly. The red muscles, which are used for long-distance walking or running, for example, use fewer calories to do their work. The white muscles, used for sudden bursts of energy in activities like lifting weights or sprinting, burn more calories. When a person’s weight is 10 percent or more above his or her natural weight, Dr. Leibel speculated, that person “may shift from predominantly red to predominantly white fibers, or have enzymes that do that.”

But, Dr. Bennett said, the answer for dieters is not in the immediate offing. “Over and over again, people have been told there’s an answer, and it’s a terrible betrayal to have people think we are close,” he said.

For now, Dr. Bennett added, “the key thing is to use the muscles.” He added: “I’m speaking from personal experience. I bought a car five years ago and gained 30 pounds.

March 9, 1995

Some Extra Heft May Be Helpful, New Study Says

By GINA KOLATA

People who are overweight but not obese have a lower risk of death than those of normal weight, federal researchers are reporting today.

The researchers—statisticians and epidemiologists from the National Cancer Institute and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—also found that increased risk of death from obesity was seen for the most part in the extremely obese, a group constituting only 8 percent of Americans.

And being very thin, even though the thinness was longstanding and unlikely to stem from disease, was correlated with a slight increase in the risk of death, the researchers said.

The new study, considered by many independent scientists to be the most rigorous yet on the effects of weight, controlled for factors like smoking, age, race and alcohol consumption in a sophisticated analysis derived from a well-known method that has been used to predict cancer risk.

It also used the federal government’s own weight categories, which define fatness and thinness according to a “body mass index” correlating weight to height, regardless of sex. For example, 5-foot-8 people weighing less than 122 pounds are underweight. If they weighed 122 to 164 pounds, their weight would be normal. They would be overweight at 165 to 196, obese at 197 to 229, and extremely obese at 230 or over.

Researchers had a full gamut of responses to the unexpected findings, being reported today in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Some saw the report as a long-needed reality check on what they consider the nation’s near-hysteria over fat.

“I love it,” said Dr. Steven Blair, president and chief executive of the Cooper Institute, a research and educational organization in Dallas that focuses on preventive medicine.

“There are people who have made up their minds that obesity and overweight are the biggest public health problem that we have to face,” Dr. Blair said. “These numbers show that maybe it’s not that big.”

Others simply did not believe the findings.

Dr. JoAnn Manson, chief of preventive medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, which is affiliated with Harvard, pointed to the university’s own study of nurses that found mortality risks in being overweight and even greater risks in being obese. (That study involved mostly white women and used statistical methods different from those in the newly reported research.)

“We can’t afford to be complacent about the epidemic of obesity,” Dr. Manson said.

In fact, the new study addressed the risk only of death and not of disability or disease. There has long been conclusive evidence that as people move from overweight to obese to extremely obese, they are more and more likely to have diabetes, high blood pressure and high cholesterol levels.

But the investigators said it was possible that being fat was less of a health risk than it used to be. They mentioned a paper, also being published today in the journal, in which researchers including Dr. Edward W. Gregg and Dr. David F. Williamson, both of the C.D.C., report that high blood pressure and high cholesterol levels are less prevalent now than they were 30 or 40 years ago, largely because of breakthroughs in medication.

As for whether there is truly a mortality risk in being underweight, Dr. Mark Mattson, a rail-thin researcher at the National Institute on Aging who is an expert on caloric restriction as a means of prolonging life, said it was not clear that eating fewer calories meant weighing so little, since some people eat very little and never get so thin. In any event, while caloric restriction may extend life, Dr. Mattson said, “there’s certainly a point where you can overdo it with caloric restriction, and we don’t know what that point is.”

Some statisticians and epidemiologists said that the study’s methods and data were exemplary and that the authors—Dr. Williamson and Dr. Katherine M. Flegal of the disease control centers, and Dr. Barry I. Graubard and Dr. Mitchell H. Gail of the cancer institute—were experienced and highly regarded scientists.

“This is a well-known group, and I thought their analysis and their statistical approaches were very good,” said Dr. Barbara Hulka, an emerita professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina.

The study did not explain why overweight appeared best as far as mortality was concerned. But Dr. Williamson said the reason might be that most people die when they are over 70. Having a bit of extra fat in old age appears to be protective, he said, giving rise to more muscle and more bone.

“It’s called the obesity paradox,” Dr. Williamson said. But, he said, while the paradox is real, the reasons are speculative. “It’s raw conjecture,” he said.

The new study comes just 13 months after different researchers from the disease control centers published a paper warning that obesity and overweight were causing an extra 400,000 deaths a year and were poised to overtake smoking as the nation’s leading preventable cause of premature death.

That conclusion caused an uproar, and scientists, particularly those who examine the consequences of smoking, questioned the study’s methods. In January, the agency’s researchers corrected calculation errors and published a revised estimate of 365,000 deaths.

Now the new study says that obesity and extreme obesity are causing about 112,000 extra deaths but that overweight is preventing about 86,000, leaving a net toll of some 26,000 deaths in all three categories combined, compared with the 34,000 extra deaths found in those who are underweight.

Dr. Donna Stroup, director of the Coordinating Center for Health Promotion at the C.D.C., noted that the previous study had used different data and different methods of analysis.

“Counting deaths is not an exact science,” Dr. Stroup said.

For now, said Dr. Dixie Snider, the disease control centers’ chief science officer, the agency will not take a position on what is the true number of deaths from obesity and overweight. “We’re too early in the science,” Dr. Snider said.

Dr. Stroup said of the new findings, “From a scientific point of view, they are a step forward.” But she added that the agency considered illness that is linked to obesity to be just as important as the number of deaths.

“Mortality really only represents the tip of the iceberg of the magnitude of the problem,” she said.

Estimating deaths due to overweight or obesity is a statistical challenge, the study’s investigators said. The idea is to determine, for each person in the population, what would be the risk of dying if that person’s weight were normal.

For people whose weight is already in that range, there would be no change in the risk, of course. But what happens to the risk for people whose weight is above or below the normal range? The idea is to control for factors like age, smoking and gender, and ask what would happen if only the weight were changed.

Now that the researchers have done their analysis, Dr. Williamson said, the message, as he sees it, is that perhaps people should take other factors into consideration when deciding whether to worry about the health risks of their weight.

Dr. Williamson, who is overweight, said that “if I had a family history—a father who had a heart attack at 52 or a brother who developed diabetes—I would actively lose weight.”

But “if my father died at 94 and my mother at 97 and I had no family history of chronic disease,” he said, “maybe I wouldn’t be as concerned.”

Dr. Barry Glassner, a sociology professor at the University of Southern California, had another perspective.

“The take-home message from this study, it seems to me, is unambiguous,” Dr. Glassner said. “What is officially deemed overweight these days is actually the optimal weight.”

April 20, 2005