LICHENS

One of the marvels of the natural world—neither plant nor animal—lichens have been described as more like an ecosystem than an individual organism. They grow through a symbiotic relationship between fungi and algae or cyanobacteria (called photobionts), both of which can photosynthesize and produce sugars and other carbohydrates. In a lichen, fungi feed off the nutrients produced by the photosynthesizers.

Approximately 20,000 to 25,000 lichen species grow worldwide from the deserts to temperate rain forests to the frozen Arctic. One study estimated that lichens form the dominant vegetation on 8 percent of Earth’s land surface. They can live on bark, wood, rock, soil, leaves, and even animals. For instance, lichens growing on a lacewing larvae help camouflage the immature insect. Often growing less than a millimeter per year, lichens can live for several thousand years, and can withstand months of drought and temperatures ranging from well below freezing to almost boiling.

Lichens range from white to black to yellow to red to green and can vary within species depending upon age, substrate, and exposure to sunlight. All of these colors occur in canyon country lichens. The vivid colors may help protect the algae from solar radiation.

Lichens are often pioneer species, colonizing bare rock. They propagate via broken fragments and fungal spores, as well as through reproductive bundles that consist of hyphae (branching, threadlike structures of fungus responsible for feeding, growing, and reproduction) and photobiont cells. As they grow, lichens help break down the rock, as hyphae penetrate into the rock. They also set the stage for vascular plants by trapping dust and seeds, and by dying, which provides organic material for soil development.

Unlike vascular plants, lichens lack true roots, leaves, and stems. They do have a body, known as a thallus (plural thalli). Thalli come primarily in three varieties. Most common are flattened crustose lichens, so tightly attached to their substrate that they cannot be pried up without destroying them. Foliose lichens look a bit more lettucelike with a leafy body that protrudes beyond the substrate. Fructose lichens grow as shrubby, branching bodies or dangle in long strands. In the Four Corners region, more than half the species are crustose. Foliose species make up 38 percent and fructose 4 percent.

HOARY COBBLESTONE LICHEN

Acarospora strigata

Acarosporaceae family

Most members of this genus are covered in pruina, or a thin layer of dead hyphae or calcium oxalate crystals. In other words, the lichen has a gray to white surface coating that looks a bit like flour or frost. Some lichenologists propose that the pruinose veneer blocks solar radiation, some that it concentrates light for cells that photosynthesize. Others think that it provides moisture via the water entrapped in the calcium oxalate crystals. Underneath the pruina, this species is dark brown, which is often visible in the center of the white coating, such that the thalli look like tiny dabs of marshmallow dotted with black eyes.

VARYING RIM-LICHEN

Lecanora argopholis

Lecanoraceae family

These yellow-green to gray lichens grow primarily on non-calcareous rocks but may also occur on mosses or plant remains. Sagebrush rim-lichen (L. garovaglii) has a light green, sagebrush color with folded lobes. They are also common on sandstone.

BROWN ROCK POSY

Rhizoplaca peltata

Lecanoraceae family

The common name refers to the superficial resemblance to flowers with some lobes flaring out above the surrounding structure. In profile, the fruiting bodies have a wineglass-like shape, with a yellow-green rim and tan center. Thalli can be more than 2 inches wide. Unlike other members of this genus, R. peltata lacks a pruinose coating on the fruiting bodies. One of many saxicolous, or rock-dwelling, species of lichens, they grow primarily on calcareous rocks.

PLITT’S ROCK SHIELD

Xanthoparmelia plittii

Parmeliaceae family

A classic-looking, light green lichen with leafy lobes, Plitt’s rock shield is one of many Xanthopermelia species growing across the Colorado Plateau. Another species X. coloradoensis is common on basalt boulders above 5,000 feet. Most species are hard to distinguish but X. chlorochroa, or tumbleweed shield lichen, is somewhat unusual with branching light green lobes that look like tiny antlers. The lobes curl inward. This lichen is even more unusual because it grows loose on soil—hence the tumbleweed moniker—and because it may be toxic to cattle, sheep, and elk. Researchers attributed the death of 400 to 500 elk in Wyoming in 2004 to lichen intoxication. In contrast, pronghorn eat tumbleweed shield lichen without any issues. Charles C. Plitt (1869–1933) was a botanist and lichenologist who had a private collection of more than 10,000 lichen specimens.

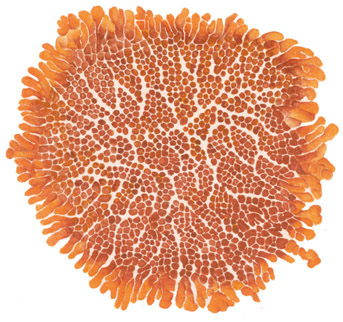

DESERT FIREDOT LICHEN

Caloplaca trachyphylla

Teloschistaceae family

This striking orange, crustose lichen grows on calcium-rich rocks, primarily sandstone, where it can form roundish bodies, several inches wide. The spreading lobes look like miniature orange mudflows fingering their way across rock. Not terribly fast growers, they spread less than ³/₅₀ inch per year. Other species of Caloplaca are also orange to yellow, though a few varieties are also gray. Another species of lichen, the whitish Acarospora stapfiana (no common name), often invades and parasitizes its more vibrantly colored cousin.

Close-up

Hanging Gardens

Despite the desert’s appearance, water is abundant; the only problem is that much of it is held within the porous sandstone. During a rainstorm most water runs off the barren surface, but some soaks into the rock and slowly percolates down. When the water encounters a less-porous rock unit, such as shale, it flows downslope until it emerges at the surface as a spring or a seep.

On vertical surfaces, the water weakens and eventually collapses the rock, forming an overhang that provides a prime microhabitat for plants to exploit—a constant supply of water that is often shaded. Animals exploit this water, too, and it is common to see a wide array of mammal tracks near these ecosystems.

Within a hanging garden environment, three different growing areas develop. One group of plants grows directly at the seep layer, where water is abundant and soil minimal. A second group of plants, generally algae, flourishes on the vertical wall below the seep. Here soil is essentially nonexistent and water constant, but less plentiful than above. The third, largest, and most diverse area forms where the vertical wall changes to a sloped wall. The water supply at this lowest level is generally good and the soil most abundant.

Recent studies have shown that hanging garden systems are extremely fragile. The main source of soil for the lowest, most accessible area comes from the collapsing walls; therefore, soil develops slowly and any damage is long lasting.

Many of the plants growing in hanging gardens are endemic to the Colorado Plateau and are found only in these moist habitats.

One of the first people to study hanging gardens was botanist Alice Eastwood, a Denver schoolteacher. She made her first studies near Bluff, Utah, in 1895. She eventually headed the California Academy of Sciences, gaining fame for saving numerous botanical specimens during the San Francisco earthquake of 1906.

Cave-dwelling primrose (Primula specuicola) is one of several plants that she discovered in the hanging garden environment. The small plant roots into the algal mat on the rock surface or within flaking rock layers. Several small lavender, five-petaled flowers grow at the end of a short stem. They bloom early in the year, giving the plant its other common name, Easter primrose. The generic epithet also refers to this early blooming habit; Primula is derived from the Latin for first, primus.

A brilliant red flower, Eastwood’s monkey-flower (Mimulus eastwoodiae), honors Eastwood’s botanical contributions. This perennial bears elliptical, dark green leaves. The 1-inch-long flowers appear in late spring and bloom into summer. Corollas flare open with three lobes hanging down and two pointing up.

Alcove columbine (Aquilegia micrantha), a relative of the better-known state flower of Colorado, grows in the lowest level of the hanging garden. The white flowers bloom throughout the summer. Columbines are generally the largest flowering plant in this environment.

Other hanging garden species include maidenhair fern (Adiantum capillusveneris), alcove bog orchid (Plantanthera zothecina), and sheathed deathcamas (Zigadenus vaginatus).