REPTILES

Lizards and snakes define deserts for many people. The deadly rattlesnake meandering up a sand dune, the elusive lizard darting under cover—these are the images we carry. There is some truth in this picture. Lizards are probably the most commonly seen animal in canyon country, after birds. With their varied diets of insects, arachnids (e.g., spiders and scorpions), and each other; and homes in trees, under rocks, and underground, reptiles are remarkably adapted and resilient. One species of lizard in particular, the Western Whiptail, may be seen scurrying about during the hottest part of a summer day.

Like all ectotherms, reptiles derive their body heat from external sources, which makes most reptiles active in the early morning and late afternoon, when temperatures are most comfortable. In the hottest part of the day, they stay in burrows or under rocks. During winter, most reptiles hibernate. The small Side-Blotched Lizard, however, is able to come out of hibernation to take advantage of warm winter days.

Ectothermic animals have several advantages over endothermic animals (e.g., birds and mammals). Reptiles need less food than endotherms because they do not have to generate their own heat. One study found that “one day’s food for a small bird will last a lizard of the same body size more than a month.” During a drought, this is especially important, because food supplies may be scarce. Neither ectotherms nor endotherms tolerate temperatures of 100° or more. Lizards are often seen performing thermoregulatory dances on hot surfaces, lifting their legs or even using their tail as a lever to elevate the rest of their body off the hot surface.

Both snakes and lizards periodically shed their epidermis (commonly, but incorrectly, called the “skin”) as they grow, although they take different approaches. Lizards slough off patches of epidermis, usually separately on the head, tail, and body. Shedding, or molting, occurs fairly regularly throughout the period of daily activity. Snakes, on the other hand, shed their entire epidermis at one time, a process that may take several hours to days. To accomplish this, a snake rubs its head or nose on a rock or stick until the old epidermis catches, then simply crawls out of the old, dry covering. In addition, rattlesnakes add a new rattle during each molt, which can occur several times a year; thus the number of rattles does not indicate a rattlesnake’s age. Shedding occurs more often in young reptiles, during the time of greatest growth.

Reptiles play an important role in the desert food web. Without snakes, the fecund rodent population would quickly grow out of control. Lizards help control insect and arachnid populations and, in one case in Utah, were found to slow down an invasion of beet leafhoppers. In turn, snakes and lizards provide a hearty meal for many animals, including birds, rodents, and other small mammals.

Common and scientific names for reptiles and amphibians conform with the Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians and Reptiles, Seventh Edition (SCCSNNAAR). Author note: Unlike what happens with the names of mammals and plants, herpetologists prefer that all reptile and amphibian names be capitalized, a practice I have adopted throughout this book.

Lizards

During the summer, lizards are a common sight throughout this region. Their small size entices many people to try to catch them. Unfortunately, the pursuer often ends up with only a writhing tail and no lizard in his or her hands. This ability to lose a tail forms the lizard’s first line of defense. In many species of lizard, the tail has weak fracture planes between the vertebra, allowing the tail to detach easily. After breaking off, the thrashing tail attracts the would-be predator, enabling the lizard to escape. In addition to having easily broken tails, some lizards have brightly colored tails (often found on young individuals), which further enhances the chance of losing only a tail instead of a life. There can be serious consequences, however, to losing one’s tail.

Lizard tails serve numerous purposes, including locomotion and balance, social status, and fat storage. A long tail acts as a counterbalance, enabling a lizard to lift its forelegs when running. Lizards move more quickly on two legs than on four, and large lizards running on two legs can sprint up to 12 miles an hour. Studies show that females lose their tail more easily than males. Males need their tail for social status, which, if low, reduces their chances to mate. Researchers have also found that tail loss may slow a juvenile’s acquisition of a home range, due to a lowered social standing. Fat stored in a tail provides a food source during periods of starvation and reproduction.

A healthy tail is critical for lizards. Do not attempt to catch lizards; you are only putting their lives at risk.

EASTERN COLLARED LIZARD

Crotaphytus collaris

Iguanidae family

3 to 4½ in. snout to vent length, 8–14 in. with tail, green body with yellow head, two black collars around neck

The bright green and yellow Collared Lizard stands out in a landscape of red rocks. These large lizards commonly perch on top of boulders, scanning their territory for prey. Large insects make up the majority of their diet, but these omnivores will also eat smaller lizards. Collared Lizards catch their prey with a quick chase, often running on their hind legs with their forelimbs lifted. One study found that a full-grown lizard has a stride of 12 inches when running in this manner.

Male Collared Lizards will defend their territory with great vigor. They may chase and/or fight an intruder but usually resort to an elaborate series of push-ups designed to display their colors. These lizards are the supermodels of the lizard world, seeming to show off their beautiful bodies, allowing humans to approach within a few feet and take pictures; however, they can and will inflict a painful bite.

Unlike short-lived species, such as Uta stansburiana, which invest a high amount of energy into one year of life, consumed by feeding and breeding, Collared Lizards instead spread out their reproduction over several years. They do not become sexually active until their second summer and then only produce two clutches per year. This life history pattern, which is more pronounced in larger lizards, usually indicates limited resources.

There is no Western Collared Lizard. The common name arises because this species has the eastern-most distribution in the genus. The closely related Great Basin Collared Lizard (C. bicinctores) also occurs in the region; it is more orange colored.

LONG-NOSED LEOPARD LIZARD

Gambelia wislizenii

Iguanidae family

3½–4½ in. snout to vent length, 8½–15½ in. with tail, variable coloration is generally tan to darker brown and temperature dependent; numerous small dark spots cover entire body

Unlike many lizard species, where the male has special breeding coloration, the female Leopard Lizard undergoes a dramatic color change during breeding season. After copulation, her undersides turn scarlet and red streaks shoot up her sides. This coloration remains for several weeks after she lays eggs.

Leopard Lizards inhabit grasslands and open habitat, where they use their speed to capture grasshoppers and other lizards, including members of their own species. If chased, they retreat under shrubs or into rodent burrows. The specific name honors Frederick Wislizenus, a German physician who traveled in the Southwest in the late 1830s and 1840s. The generic name honors William Gambel (1821–1849), an American naturalist, who died at the age of 28 on an ill-fated winter crossing of the Sierra Nevada.

DESERT SPINY LIZARD

Sceloporus magister

Iguanidae family

3½–5½ in. snout to vent length, 7–12 in. with tail, pale yellow to yellowish brown with vague, dorsal crossbands or spots; both male and female adults have yellowish orange on head, most prominent scales of any Sceloporus

Throughout their range, Desert Spiny Lizards inhabit a variety of habitats. In some areas they are primarily a tree- or shrub-dwelling species, only moving down onto the ground to capture prey. In canyon country, Spiny Lizards move about between shrubs, boulders, and canyon walls. Although these omnivores occasionally eat other lizards, beetles constitute the majority of their diet.

An arboreal lifestyle has led to several adaptations. Tree-dwelling Sceloporus species have shorter hind legs than ground-dwelling Sceloporus. Climbing species tolerate a narrower range of temperature variation. When an arboreal species needs to cool down, it only has to move slightly to find shade. In addition, they do not have to expend energy, which alters body temperature, running from rock to rock or shrub to shrub.

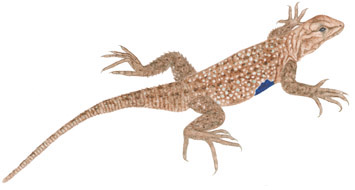

PLATEAU FENCE LIZARD

Sceloporus tristichus

Iguanidae family

1⅝–3¼ in. snout to vent length, 4–7 in. with tail, gray, brown with lengthwise stripes, blue on throat usually divided into two patches

Sceloporus lizards are commonly called swifts or blue bellies due to the blue markings found on the undersides of males. During mating, the males employ an elaborate series of movements including bowing, head bobbing, flattening of the sides, and push-ups, all oriented toward displaying their blue markings. Similar gestures are also used during territorial displays.

These common lizards scamper amongst rocks and shrubs throughout the day, using their long claws for climbing. Like many lizards, Plateau Fence Lizards have catholic diets that include spiders, beetles, ticks, and other small arthropods. They were formerly known as Eastern Fence Lizards.

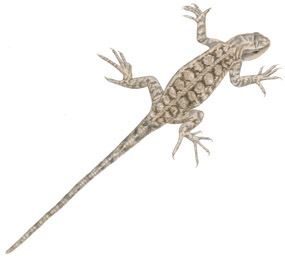

COMMON SAGEBRUSH LIZARD

Sceloporus graciosus

Iguanidae family

1⅞–2⅝ in. snout to vent length, 5–6¼ in. with tail, gray, brown with blotches on upper side, rust-colored behind forelimbs, small scales

Sagebrush Lizards inhabit areas with scattered shrubs and open ground. In the canyonlands region, they often occur at higher elevations than most other lizards. They do not venture far from the protective refuge of bushes, rock outcrops, or rodent burrows. Although Sagebrush Lizards are primarily ground dwellers, preferring gravelly soils, they will climb shrubs or boulders in pursuit of prey. They primarily eat insects but may indulge in spiders and scorpions.

Sagebrush Lizards closely resemble the Plateau Fence Lizard in appearance, but they have an entirely blue throat and rust or light orange on their sides.

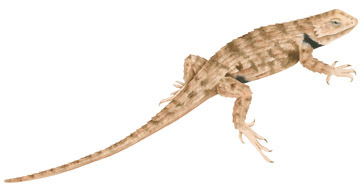

COMMON SIDE-BLOTCHED LIZARD

Uta stansburiana

Iguanidae family

1½ –2⅜ in. snout to vent length, 4–6⅜ in. with tail, brownish with blue-black blotch behind forelimbs, no distinct blue belly markings

Side-Blotched Lizards have a typical daily lizard lifestyle of morning and evening basking interrupted by occasional feeding. Like most lizards, they are opportunistic feeders, attacking any suitable prey when encountered. When not basking or feeding, they retreat to cooler spots under plants or rocks. During winter, however, when most lizards are hibernating, Side-Blotched Lizards take advantage of their small body size, which facilitates quick warming, to move around on warm days.

Side-Blotched Lizard populations have essentially an annual turnover with an individual normal life expectancy of about 5 months, although they can live for 2 years. They quickly reach sexual maturity and can produce several clutches of three to four eggs. Side-Blotched Lizards have evolved this life history to take advantage of abundant food resources (see Eastern Collared Lizard, page 160, for comparison). In low food production years, though, fewer clutches are laid.

The common name refers to the dark blue or black spot located behind each forelimb, which is a key identification characteristic. The specific name honors Captain Howard Stansbury, who led a US government mapping expedition to the Great Salt Lake in 1849. His vast collection included plants, reptiles, birds, and mammals.

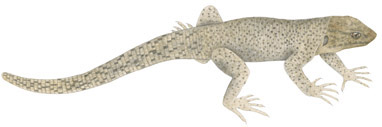

ORNATE TREE LIZARD

Urosaurus ornatus

Iguanidae family

1½–2¼ in. snout to vent length, 4½–6¼ in. with tail, brown to gray body with light-edged darker crossbands on back

Despite their common name, Tree Lizards do not live in trees. They prefer to forage on boulders, cliffs, and shrubs in a riparian habitat. Males usually perch higher than females, allowing them to search for mates and potential territorial intruders. Females remain closer to the ground to search efficiently for food needed during egg production. After breeding season, females perch higher because males no longer harass them.

Tree Lizards have similar habits to the Side-Blotched Lizard, and at one time herpetologists placed them in the same genus, Uta. Although one might expect fierce competition between these lizards (due to their similar size, habits, and habitats), each species exploits separate microhabitats or has a slightly different diet. For example, Tree Lizards remain closer to the water’s edge than Side-Blotched Lizards.

To identify a Tree Lizard, look for a series of interconnecting Y-shaped crossbands on its back.

GREATER SHORT-HORNED LIZARD

Phrynosoma hernandesi

Iguanidae family

2½–4 in. snout to vent length, short, stubby, reddish horns; coloration generally similar to background soil color

Due to the low nutrient value of ants, their primary food source, horned lizards have evolved extremely large stomachs, which make up 13 percent of their body weight. This large gut has led to a short, round body instead of the usual long, skinny lizard body. As a result, horned lizards do not run very fast. They rely on their coloring, which generally matches the surrounding soil, as their first line of defense against predators. If discovered by a predator, a horned lizard can quickly inflate its body with air, so that it resembles a tiny, spiny, armored tank.

One well-known horned lizard trait, squirting blood from its eyes, is not practiced by Short-Horned Lizards. This defensive feat occurs only in Texas and Regal-Horned Lizards, both of which live south and east of canyon country. Those lizards can shoot a thin stream of blood as far as 4 feet.

Short-Horned Lizards have the widest distribution of any horned lizard, ranging from Canada to Mexico and living at elevations up to 11,000 feet. They have adapted to cold climates by giving birth to live young (five to twenty-three at a time), an unusual trait among horned lizards. Live birth provides several advantages over laying eggs. The warmth of the pregnant female ensures that the young develop safely and much more quickly. In contrast, cold soil exposes eggs to dangerously low temperatures. Live-born young are larger and have more time to locate a safe place for brumation as winter approaches.

The closely related Desert Horned Lizards (P. platyrhinos) have reportedly been seen in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area and Zion National Park. The desert variety inhabits shrubby semiarid or arid regions, while the Short-Horned Lizard is found in open plant communities of the piñon-juniper and higher elevation forests.

DESERT NIGHT LIZARD

Xantusia vigilis

Xantusiidae family

1½–1¾ in. snout to vent length, 4–6 in. with tail, olive, gray speckled with black, vertical pupils with no eyelids

Until recently, Desert Night Lizards were considered uncommon, but this may not be the case. Now herpetologists believe that Desert Night Lizards are secretive, spending almost all of their time under vegetation, especially yucca. In 1857 a Hungarian working for the US Army, John Xantus, made the first scientific discovery of this species near Bakersfield, California. Spencer Baird, one of the nineteenth century’s most important cataloguers of birds and reptiles, named the night lizard after Xantus.

Desert Night Lizards possess many unusual characteristics. Instead of laying eggs, females give birth to one or two live young, which after much prodding and nipping emerge upside down and tail first. After birth the female eats the fetal membrane, a trait unknown in other American lizards. The animal’s life expectancy is 4 years, and some individuals live for at least 9 years. And unlike most lizards, Desert Night Lizards are darker during the day and lighter at night, reflecting their nocturnal habits.

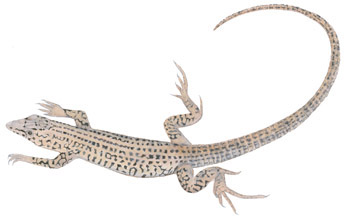

TIGER WHIPTAIL

Aspidoscelis tigris

Teiidae family

2⅜–4½ in. snout to vent length, 8–12 in. with tail, gray, brown with a network of black markings that form rows lengthwise on back

One commonly sees Tiger Whiptails darting and dashing around in search of food during summer days. This active foraging technique is uncommon among western North American lizards; most lizards employ the “sit-and-wait” hunting method. This species’ common name comes from its tail, which is up to 2½ times as long as the body. Whiptails flick their tails from side to side as they run, providing attractive objects for predators. It’s always better to lose a tail than a life.

Tiger Whiptails constantly use their exceptionally long, forked tongues to probe for airborne chemicals. One study found that they flick out their tongue an average of 456 times each hour. The Jacobson’s organ, a chemosensory organ also found in snakes, sends this chemical information directly to the brain for processing. Whiptails may use this information for food seeking, sexual recognition, courtship, or communication, unlike other lizards that rely on color and body gestures for most communication.

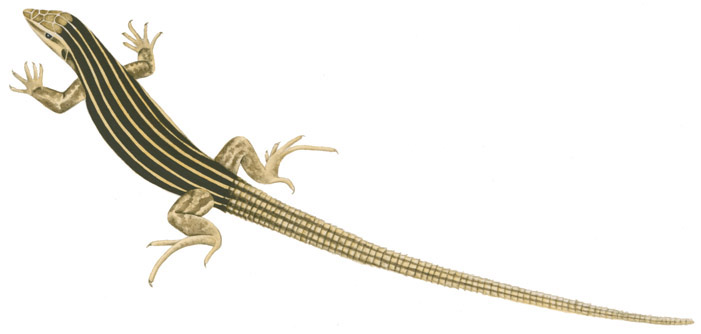

PLATEAU STRIPED WHIPTAIL

Aspidoscelis velox

Teiidae family

2½–3⅜ in. snout to vent length, 8–12 in. with tail, 6 to 7 dorsal stripes, light blue tail, whitish below

No males occur in this species. Females produce unfertilized, but viable, eggs—all clones of the mother. This process, known as parthenogenesis (Greek for “virgin birth”), offers several advantages. Because all individuals are female, Plateau Striped Whiptails can reproduce at a more rapid rate than species that have both sexes, half of whom cannot lay eggs. Parthenogenetic lizards can colonize new territory more easily, because it takes only one individual to create a new population. Clones, however, are more susceptible to disease and less adaptable to changing environmental conditions.

Plateau Striped Whiptails evolved through the mating of two different species, which produced mostly sterile males and females; however, a few females must have been capable of reproducing by themselves. Six of the twelve species of whiptail in the Southwest reproduce parthenogenetically.

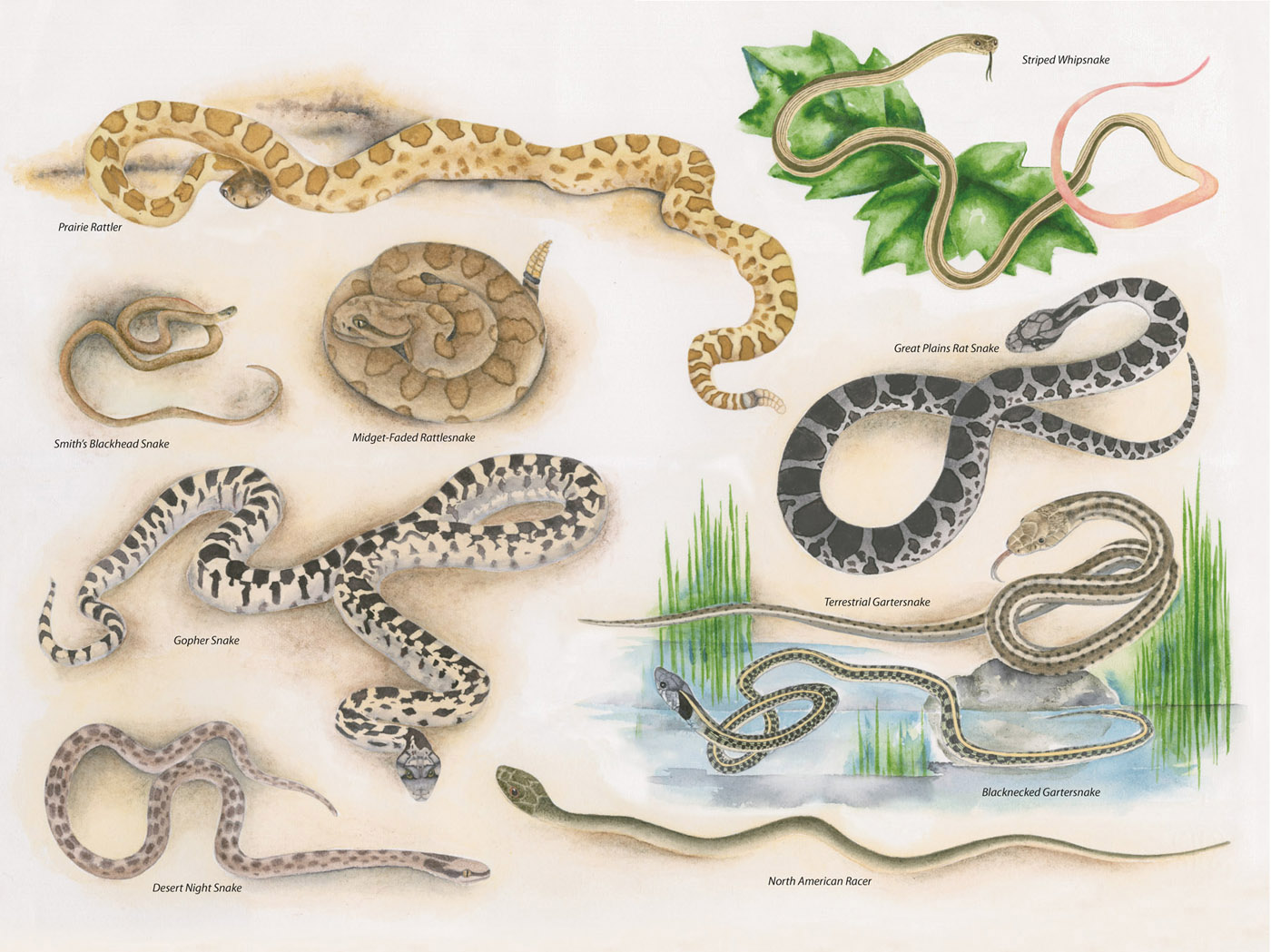

Snakes

Eleven species of snake occur in southeast Utah, ranging in size from 15 to 72 inches. Most only come out at night, avoiding the heat of a summer day (most snakes cannot tolerate temperatures above 100°F). They live in a variety of habitats, including streamsides, grasslands, rocky slopes, and piñon-juniper woodlands.

All serpents are carnivorous and can swallow objects much larger than themselves. Prey is secured in several different manners. Rattlesnakes and night snakes inject a toxin to subdue prey. Gopher and rat snakes seize their meals and squeeze them to death, while racers hold their quarry down with their coils. Gartersnakes simply bite their prey, overpower it, and swallow.

Snakes use several different sensory organs to locate prey. They possess well-developed eyesight, although it is most useful at close range.

Please note: Most snakes will try to avoid you, but if you harass them, snakes can and will bite. Rattlesnakes are the only snake that can inject a potentially fatal venom. Most studies, however, show that only about one-third of all rattler bites inject a dangerous quantity of venom; roughly one-third of all bites inject no venom, while the other one-third inject only a minute amount. If you are bitten, remain calm and go to the nearest medical facility. Do not apply ice. Do not use a tourniquet. Do not make an incision and try to suck out the venom.

One further note: Do not pick up a rattlesnake even if it is dead. A recent study described five people who were bitten by snakes that they had recently killed. One victim had to have a finger amputated. All of the victims were males between the ages of 20 and 35, who are statistically the most commonly bitten people, especially when they have been drinking.

NORTH AMERICAN RACER

Coluber constrictor

Colubridae family

33–54 in., usually less than 36 in., no markings, uniformly colored brownish olive with yellow belly; juveniles have dark blotches similar to gopher snake

These active, fast-moving snakes inhabit open habitats of piñon-juniper or sagebrush. Although principally ground dwelling, they climb trees with ease and celerity. When hunting, racers hold their head and neck above the ground. They kill by using a loop of their own body to hold down prey.

Females lay white, leathery eggs under rocks, rotting logs, or in moist sand in early summer. When the young break out of the eggs, they do not look like adults at all. Instead, bold blotches and spots cover the juvenile racers. This coloration eventually fades after 2 or 3 years.

As cooler weather sets in, racers migrate to communal den sites. Once at the site they may remain outside for a few weeks. They often den with Striped Whipsnakes, Gopher Snakes, night snakes, and gartersnakes.

STRIPED WHIPSNAKE

Coluber taeniatus

Colubridae family

36–60 in., black to brown with four narrow stripes that run length of body, top two more distinct than bottom ones

The whipsnake is one of the fastest-moving snakes in canyon country. It inhabits piñon-juniper woodlands and sage flats, hunting during the day for lizards, snakes, and small rodents. The Striped Whipsnake moves

equally well on the ground or through the foliage of shrubs and trees. If captured, it may inflict a bite that can puncture the skin. The snake is not venomous.

GREAT PLAINS RAT SNAKE

Pantherophis emoryi

Colubridae family

36–72 in., varied color but usually light gray with dark-edged brown blotches on back, pair of neck blotches unite to form a spear point between eyes on top of head

This species primarily occurs in the Great Plains region of the United States, but a distinct subspecies inhabits the Colorado River basin of Utah and Colorado. Like the gartersnakes, rat snakes may void their anal scent glands when distressed. They frequent a variety of habitats and are primarily ground dwellers. During the summer months they emerge from burrows at night to search for small mammals, which they kill by constriction. For many years, this rat snake was known as Elaphe guttata. Emoryi honors William H. Emory, a topographic engineer who worked on both the Mexican-US and Canadian-US borders.

GOPHER SNAKE

Pituophis catenifer

Colubridae family

30–72 in., ground color, usually light brown to yellowish with darker blotches

In his book Desert Solitaire, Edward Abbey befriended a Gopher Snake to help keep rattlesnakes away from his trailer in Arches National Monument. It worked. In contrast, many people indiscriminately kill Gopher Snakes because their body coloration resembles that of rattlesnakes and because they vibrate their tail and hiss when threatened. In dry leaves the vibrating tail produces a rattlelike sound.

Gopher Snakes kill their prey, which includes squirrels, mice, and birds, by constriction. They incapacitate their prey by one of three methods: a simple holding down or pinioning, a pinion with a non-overlapping loop, or fully encircling coils. Prey handling depends both on size and prey type; larger and/or more active species receive more attention. Obtaining a larger meal must be weighed against the consequences of being more vulnerable to predation.

A diurnal species, Gopher Snakes are one of the most commonly seen snakes in canyon country. They live in a variety of habitats, ranging from piñon-juniper to open grasslands to rocky slopes. They are also known as bullsnakes, though like many common names, it isn’t clear why. One herpetologist told me that he had heard that it could be because the snakes have “bullish,” or aggressive, behavior or because they are “strong as a bull.”

SMITH’S BLACKHEAD SNAKE

Tantilla hobartsmithi

Colubridae family

7–15 in., uniformly tan or brown with distinct black cap on head

These small, burrowing snakes live beneath rocks, logs, or fallen yucca in the piñon-juniper ecosystem. Smith’s Blackhead Snakes are so thoroughly adapted to a subterranean lifestyle that their eyes are almost rudimentary. Their miniature skulls facilitate slithering through the smallest cracks. They eat worms, millipedes, and burrowing insect larvae.

Blackheads are relatively well adapted to cool weather for this genus, which predominantly lives in the tropics. Cold winters, though, will drive them several feet down into the ground.

Hobart Muir Smith wrote more papers on herpetology, at least 1,600, than anyone else.

MIDGET-FADED RATTLESNAKE

Crotalus oreganus concolor

Crotalidae family

24–30 in., tan to creamish body, with barely discernible darker blotches

GREAT BASIN RATTLESNAKE

Crotalus oreganus lutosus

Crotalidae family

36–60 in., light brown, dark dorsal blotches with margin in black

PRAIRIE RATTLESNAKE

Crotalus viridis

Crotalidae family

36–48 in., greenish coloration, large, rounded, and well-separated brown blotches with a white margin

These three species were long described as three subspecies of the widely distributed Western Rattlesnake (Crotalus viridis). They were then described as individual species but were recently reevaluated, leaving them in their present status, which will probably change again. The three rattlers are extremely hard to tell apart; it is usually better to rely on location instead of color or patterns. Prairie Rattlesnakes are the most widely distributed subspecies, ranging from Canada to Mexico. Midget-Fadeds only inhabit the drainages of the Colorado and Green Rivers in eastern Utah and southern Wyoming. In this area, the Midget-Faded occurs in Arches and Canyonlands National Parks but interbreeds with the Prairie at Natural Bridges National Monument. The Great Basin species ranges from western Utah across most of Nevada.

Although Midget-Fadeds are one of the smallest rattlesnakes, they employ an extremely toxic venom. The neurotoxic venom attacks the body systemically, producing respiratory problems. As with most rattlesnakes, a full venom injection occurs in only about one-third of all bites. These nonaggressive snakes inhabit small burrows and rock crevices, and can form dens of several hundred hibernating individuals during winter.

During the day rattlesnakes stay cool in the shade of a shrub or tree. At night they hunt for food, using their loreal pits, heat-sensitive depressions located slightly behind the nostrils, to locate prey. The loreal pits detect changes in temperatures well enough to allow a snake to locate a mouse up to a foot away in complete darkness. Most rattlesnakes’ coloration makes them hard to see, but they will warn you with a high-pitched rattle if you approach too closely.

Studies in Wyoming show that Prairie Rattlesnakes emerge from dens in early April and migrate up to 12 miles in almost straight lines in search of their main prey, deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus). Local populations migrate shorter distances due to rougher terrain and a more evenly distributed prey base.

After hibernation, Prairie Rattlesnakes separate into two distinct groups: males and non-pregnant females, which migrate from the den; and pregnant females, which form a communal birthing area. Rattlesnakes give birth to live young in the late summer and remain with their progeny until the newborn snakes shed their first layer of epidermis, a process that takes 2 to 3 weeks. The female then leaves a scent trail for the young to use to find their way back to the hibernation area.

Rattlesnakes kill their prey through venom secreted from two retractable fangs. The fragile fangs are constantly replaced throughout a snake’s life. Similar to most reptiles, rattlesnakes employ a “sit-and-wait” method of hunting, but on occasion will go in search of food. If the victim is small enough, the snake will simply kill it and swallow it. If the quarry is too large, a rattlesnake will bite it, injecting venom, let the victim escape, and then locate it after it dies.

DESERT NIGHT SNAKE

Hypsiglena chlorophaea

Dipsadidae family

12–26 in., light-colored with numerous small dark spots and a pair of larger dark blotches on neck, vertical pupils

An aptly named serpent, the Desert Night Snake spends the daylight hours under rocks or plant debris, only coming out during the nocturnal hours. It subdues its prey with a mildly toxic saliva that is secreted from enlarged teeth in the back of the upper jaw. The bite is not poisonous to humans. Night snakes find their prey—lizards, toads, and insects—throughout their rocky habitat.

BLACKNECKED GARTERSNAKE

Thamnophis cyrtopsis

Natricidae family

16–43 in., whitish-yellow middorsal stripe, two black blotches at back of head

Blacknecked Gartersnakes are aquatic habitat specialists, rarely traveling far from water. They employ two different hunting methods, dependent upon water and prey availability. In spring, with abundant water and habitats, Blacknecked Garters forage widely to locate relatively sedentary prey. In summer, when prey is restricted to only a few deep pools, the snakes use a “sit-and-wait” method to obtain active frogs and tadpoles.

During the cooler months of April or May, Blacknecked Garters may be seen basking on streamside rocks. If pursued, they usually enter the water, where they swim on the surface instead of underwater. Captured individuals sometimes discharge excrement and the contents of their anal scent glands, which generally deters most aggressors.

TERRESTRIAL GARTERSNAKE

Thamnophis elegans

Natricidae family

18–43 in., dull-colored with well-defined, yellowish middorsal and side stripes

Terrestrial Gartersnakes range throughout the western United States from sea level to mountains. Some are primarily terrestrial and others principally aquatic. Our local subspecies does not require permanent water but is seldom found far from a source, which it will enter to escape from a predator by swimming below the water surface. They feed on amphibians, small mammals, fish, and insects.

Unlike most snakes, gartersnakes give birth to live young. In midsummer, four to nineteen young work their way out of a translucent sac inside the female. The 5- to 7-inch-long snakes look exactly like the adults. The name “gartersnake” supposedly came about because the striped pattern resembled the pattern found on garters designed to hold men’s socks in place.